По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

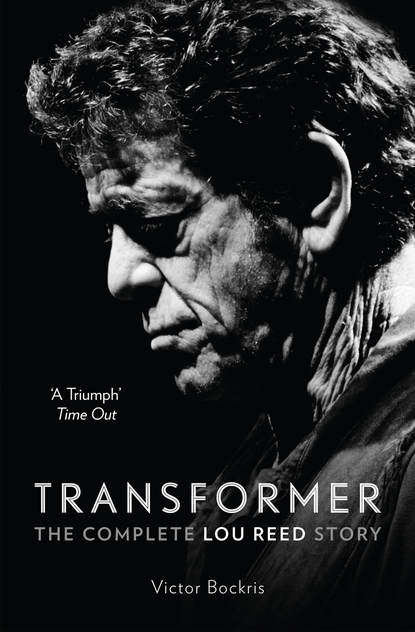

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Having met his male counterpart, Lou now needed, in order to pull out the male and female sides warring within him, a female companion. Within a week of settling in with Swados, Lou saw her riding down the university’s main drag, Marshall Street, in the front seat of a car driven by a blond football player who belonged to the other Jewish fraternity on campus and recognized Reed as their local holy fool. Thinking to amuse his date, a scintillatingly beautiful freshman from the Midwest named Shelley Albin, he pulled over, laughing, and said, “Here’s Lou! He’s very shocking and evil!” making, as it turned out for him, the dreadful mistake of offering “the lunatic” a ride.

Although in no way as twisted and bent as Lincoln Swados, Shelley was as perfect a match for Lou as his roommate was. Born in Wisconsin, where she had lived the frustrated life of a beatnik tomboy, Shelley had elected Syracuse because it was the only university her parents would let her attend. In preparation for the big move away from home, Shelley, along with a childhood girlfriend, had come to Syracuse fully intending to mend her ways and acquiesce to the college and culture’s coed requirements. Discarding the jeans and work shirts she wore at home, she donned instead the below-the-knee skirt, tasteful blouse, and string of pearls seen on girls in every yearbook photo of the period. When Lou hopped into the backseat eager to make her acquaintance, Shelley was squirming with the discomfort of the demure uniform as well as her dorky date’s running commentary.

She vividly recalled Lou’s skinny hips, baby face, give-away eyes, and knew “we were going to go out as soon as he got into the car.” She also knew she was making a momentous decision and that Lou was going to be trouble, but that it certainly wasn’t going to be boring. “It was such a relief to see Lou, who was to me a normal person. And I was intrigued by the evil shit.”

The feeling was clearly mutual. As soon as the couple let Lou off in front of his dorm, Reed sprinted into their room and breathlessly told Swados about the most beautiful girl in the world he had just met, and his plans to call her immediately.

Lincoln had a strangely paternal side that would often appear at inappropriate moments. Seeing his role as steering Lou through his emotional mood swings, Swados immediately put the kibosh on Reed’s notion of seducing Shelley by informing him that this would be out of the question since he, Lincoln, had already spotted the pretty coed and, despite not yet having met her, was claiming her as his own.

Lou, for his part, saw his role in the relationship as primarily to calm the highly strung, hyperactive Swados. Reasoning that the nerdy Lincoln, who had been unable to get a single date during the freshman year, would only be wounded by the rejection he was certain to get from Shelley, Lou wasted no time in cutting his friend off at the pass by calling Shelley at her dorm within the hour and arranging an immediate date. That way, Lou told himself, he would soon be able to give Swados the pleasure of her company.

Shelley Albin would not only become Lou Reed’s girlfriend through his sophomore and junior years—“my mountaintop, my peak,” as he would later describe her—but would remain for many years thereafter his muse. “Lou and I connected when we were too young to really put it into words,” Shelley said. “There was some innate connection there that was very strong. I knew him before everything was covered up. My strongest image of Lou is always as a Byronesque character, a very sweet young man. He was interesting, he wasn’t one of the bland, robotic people, he had a wonderful poetic nature. Basically, Lou was a puffball, he was a sweetie.” For all of Lou’s eccentricities, Shelley found him “very straight. He was very coordinated, a good dancer, and he could play a good game of tennis. His criteria for life were equally straight. He was a fifties guy, the husband of the house, the God. He wanted a woman who was the end-all Barbie and would make bacon when he wanted bacon. I was very submissive and naive and that’s what appealed to him.”

But Lou also had his “crazy” side, which he played to the hilt. Like many bright kids who have just discovered Kierkegaard and Camus, he was the classic, arty bad boy. Alternating between straight and scary, Lou reveled in both. “There was a part of Lou that was forever fifteen, and a part of him that was a hundred,” Shelley fondly recalled. Fortunately for Lou, she embraced both parts equally. And going out with Lou gave Shelley the jolt she needed to throw off her skirt and pearls for jeans and let her perm return to her natural long, straight hair. Seeing her metamorphosis, the boy Shelley had left so brazenly for Lou was soon chiding her, “You went to the dogs and became a beatnik. Lou ruined you!” In fact, Shelley, an art student, had simply reverted to being herself. But she enjoyed the taunt, knowing how much Lou liked it when people accused him of corrupting her and enjoyed the notoriety it won him. Shelley was also astonishingly beautiful, and to this day, Lou’s Syracuse teachers and friends remember above all else that Lou Reed had an “outrageously gorgeous girlfriend who was also very, very nice.”

Shelley Albin had a unique face. Looked at straight on, what struck you first were her eyes. An inner light glimmered through them. Her nose was straight and perfect. Her jawline and chin were so finely sculpted they became the subject of many an art student at Syracuse. It was an open and closed face. Her mouth said yes. Yet her eyes had a Modigliani/Madonna quality that bayed, you keep your distance. Her light brown hair reflected in her pale cream skin gave it at times, a reddish tint. At five feet seven inches and weighing 115 pounds, she was close enough in size to Lou to wear his clothes.

“We were inseparable from the moment we met,” Shelley recalled. “We were always literally wrapped up in each other like a pretzel.” Soon Shelley and Lou could be seen at the Savoy, making out in public for hours at a time: “He was a great kisser and well coordinated. I always thought of him as a master of the slow dance. When we met, it was like long-lost friends.” For both of them it was their first real love affair. They quickly discovered that they could relate across the boards. They had a great sexual relationship. They played basketball and tennis together. When Lou wrote a poem or a story, Shelley found herself doing a drawing or a painting that perfectly illustrated it. She had been sent to a psychiatrist in her teens for refusing to speak to her father for three years. Lou wrote “I’ll Be Your Mirror” two years later about Shelley. And Shelley was Lou’s mirror. Just as he had rushed a fraternity, she, much to his delight, rushed a sorority and then told them to go fuck themselves an hour after she got accepted.

“His appeal was as a very sexy, intricate and convoluted boy/man,” Shelley said. “It was the combination of private gentle lover and romantic and strong, driven thug. He was, however, a little too strong, a dangerous little boy you can’t trust who will turn on you and is much stronger than you think. He had the strength of a man. You really couldn’t win. You had to catch him by surprise if you wanted to deck him.

“The electroshock treatments were very fresh in his mind when we met. He immediately established that he was erratic, undependable, and dangerous, and that he was going to control any situation by making everyone around him nervous. It was the ultimate game of chicken. But I could play Lou’s game too, that’s why we got along so well.

“What appealed to me about Lou was that he always pushed the edge. That’s what really attracted me to him. I was submissive to Lou as part of my gift to him, but he wasn’t controlling me. If you look back at who’s got the power in the relationship, it will turn out that it wasn’t him.”

Whereas the entrance of a stunning female often offsets the male bonding between collaborators, in the tradition of the beats established by Kerouac and his friend Neal Cassady, Lou correctly presumed that Shelley would enhance, rather than break up, his collaboration with Lincoln. In fact, it became such a close relationship that Lou would occasionally suggest, only half-jokingly, that Shelley should spend some time in bed with Lincoln. Their relationship mirrored that of the famous trio at the core of their generation’s favorite film, Rebel Without a Cause, with Lou as James Dean, Shelley as Natalie Wood, and Lincoln as the doomed Sal Mineo.

Lou presented Lincoln to Shelley as an important but fragile figure who needed to be nurtured. Lincoln was homely, but Shelley’s vision of him in motion was “like Fred Astaire, Lincoln was debonair and he would spin a wonderful tale and I think Lou could see this fascination. Lou felt very responsible and protective toward Lincoln because nobody would see Lincoln and we liked Lincoln.” The first thing Lou said to Shelley was, “Lincoln wants you, and if I were a really good guy, I should give you to Lincoln because I can get anybody and Lincoln can’t. Lincoln loves you, but I’m not going to give you to him because I want you.” Shelley realized that many of Lou’s ways of being charming and his gestures were taken straight from Lincoln. “A lot of what I really loved about Lou was Lincoln, who was in many ways like Jiminy Cricket standing on Lou’s shoulder, whispering words into his ear. They were going to take care of me and straighten me out and educate me.”

The most important thing about Lincoln and Shelley was their understanding and embracing of Lou’s talent and personality. If Lincoln was a flat mirror for Lou, Shelley was multidimensional, reflecting Lou’s many sides. Perceptive and intuitive, she understood that Lou appreciated events on many different levels and often saw things others didn’t. For the first time in his life Lou found two people to whom he could actually open up without fear of being ridiculed or taken for a ride. For a person who depended so much on others to complete him, they were irreplaceable allies.

Initially, Lou’s first love affair was idyllic. Lou rarely arose before noon, since he stayed up all night. He and Shelley would sometimes meet in the snow at 6 a.m. at the bottom of the steps leading to the women’s dorm. Or else in the early afternoon she would take the twenty-minute hike from the women’s dorm to Lou and Lincoln’s quarters. Like all coeds on campus, she was forbidden to enter a men’s dorm on threat of expulsion, so she would merely tap on their basement window and wait for Lou to appear. When he did, he would gaze up at one of his favorite views of his lover’s face smiling down at him with her long hair and a scarf hanging down. “I liked looking in on their pit,” she recalled. “It was truly a netherworld. I liked being outside. I liked my freedom. And Lou liked that I had to go back to the dorm every night.” From there, the threesome would repair to a booth at the Savoy where they would be joined by art student Karl Stoecker—a close friend of Shelley’s—and English major Peter Locke, a friend of Lou’s to this day, along with Jim Tucker, Sterling Morrison, and a host of others, to commence an all-day session of writing, talking, making out, guitar playing, and drawing. Lou was concentrating on playing his acoustic guitar and writing folk songs. The rest of the time was spent napping, with an occasional sortie to a class. When the threesome got restless at the Savoy, they might repair to the quaint Corner Bookstore, just half a block away, or the Orange Bar. But they always came back to home base at the Savoy, and to the avuncular owner, Gus Joseph, who saw kids come and go for fifty years, but remembered Lou as being special.

***

Lou was so enamored of Shelley that in the fall of 1961 he decided to bring her home to Freeport for the Christmas/Hanukkah holidays. Considering the extent to which Lou based his rebellious posture on the theme of his difficult childhood, Shelley was fully aware of how hard it would be for Lou to take her to his parents’ home. She remembered him thinking that he would score points with his parents: “It was sort of subtle. He was going to show his father that he was okay. He knew that they would like me. And I suspect in some ways he still wanted to please his parents and he wanted to bring home somebody that he could bring home.”

Much to her surprise, Lou’s parents welcomed her to their Freeport home with open arms, making her feel comfortable and accepted. Lou had given her the definite impression that his mother did not love him, but to Shelley, Toby Reed was a warm and wonderful woman, anything but selfish. And Sidney Reed, described by Lou as a stern disciplinarian, seemed equally loving. They appeared to be the exact opposite of the way Lou had portrayed them. In her impression, Mr. Reed “would have walked over the coals for Lou.”

At the same time Shelley realized that Lou was just like them. He not only looked like them, but possessed all their best qualities. However, when she made the mistake of communicating her positive reaction, commenting on the wonderful twinkle in Mr. Reed’s eyes and noting how similar his dry sense of humor was to Lou’s, her boyfriend snapped, “Don’t you know they’re killers?!”

Given their kind, gracious, outgoing manner, the Reeds were sitting ducks for Lou’s brand of torture. He would usually begin by embracing the rogue cousin in the Reed family called Judy. As soon he got home, Lou would enthusiastically inquire after her activities and prattle on about how he wanted to emulate her more than anyone else in the family, often reducing his mother to tears. Next, Lou would make a bid to monopolize the attentions of thirteen-year-old Elizabeth. Confiding to her his innermost thoughts, he would make a big point of excluding his parents from the powwow. “She was cute,” thought Shelley, “she looked just like Lou. So did his mother and father. They all looked exactly like him. It was hysterical. Lou was very protective of her. And she was so sweet. She didn’t have that much of a personality, but she was not unanimated.” Every action aimed to cut his parents out of his life, while keeping them prisoners in it. Meanwhile, like every college kid home on vacation, Lou managed to extract from them all the money he could, and the freedom to come and go as if the house were a hotel. As soon as everybody at 35 Oakfield Avenue was in position ready to do exactly as he wanted, Lou began to enjoy himself.

In fact, so extreme was the situation that, on this first visit, Toby Reed, looking upon her as the perfect daughter-in-law, took Shelley into her confidence. “They were very nervous about what was he bringing home,” she remembered. “So they really took it as a sign that, ‘Oh, God, maybe he was okay.’ We recognized with each other, she and I, that we both really liked him and we both loved him.” Mrs. Reed filled her in on Lou’s troublesome side and tried to find out what Lou was saying about his parents. Shelley got the impression that the Reeds bore no malice toward Lou, but just wanted the best for him. Mrs. Reed seemed completely puzzled as to how Lou had gotten on the track of hating and blaming them. Pondering the strange state of affairs unfolding behind the facade of the Reeds’ attractive home, Shelley drew two conclusions. On the one hand, since his family seemed quite normal and had no apparent problems, Lou was moved to create psychodrama in order to fuel his writing. On the other hand, Lou really did crave his parents’ approval. He was immensely troubled by their refusal to recognize his talent and needed to break away from their restricted life. One point of Lou’s frustration was the feeling that his father was a wimp who gave over control of his life to his wife. This both horrified and fascinated Lou, who was a dyed-in-the-wool male supremacist. Lou was secretly proud of his father and wanted more than anything else for the old man to stand up for himself. But Lou simply could not stand the thought of sharing the former beauty queen’s attention with his father.

After spending a wonderful, if at times tense, week in the Reed household, Shelley put together the puzzle. In a war of wits that had been going on for years, Lou went on the offensive as soon as he stepped through the portals of his home. Attempting by any means necessary to horrify and paralyze his loving parents, Lou had learned to control them by threatening to explode at any moment with some vicious remark or irrational act that would shatter their carefully developed harmony. For example, one night Mr. Reed gave Lou the keys to the family car, a Ford Fairlane, and some money to take Shelley out to dinner in New York. However, such an exchange between father and son could not pass without conflict straight out of a cartoon. As Lou was heading for the door with Shelley, Sid had to observe that if he were going to the city, he might, under the circumstances, put on a clean shirt. Instantly spinning into a vortex of anger that made Sid feel like a cockroach, Lou threw an acerbic verbal dart at his mother before slamming out the door.

On the way into New York he almost killed himself and Shelley by driving carelessly and with little awareness of his surroundings. “I remember him taking this little flower from the Midwest to the big city,” Shelley said. “Chinatown. We drove in a hair-raising ride I’ll never forget in my whole life. Lou showed me how to hang out on the heating grate of the Village Gate so you could hear the music and stay warm.”

His parents, she realized, “had no sense of what was really in his mind, and they were very upset and frightened by what awful things he was thinking. He must have been really miserable, how scary.” As a result, in order to obviate any disturbance, Lou’s tense and nervous family attended to his every need just as if he were the perennial prodigal son. The only person in the house who received any regular affection from Lou was his little sister, Elizabeth, who had always doted on Lou and thought he was the best.

However, at least for the time being, Lou’s introduction of Shelley into their lives caused his parents unexpected joy. Ecstatic that his son had brought home a clean, white, beautiful Jewish girl, Mr. Reed increased Lou’s allowance.

If he had had any idea of the life Lou and Shelley were leading at Syracuse, he would probably have acted in the reverse. As the year wore on, sex, drugs, rock and roll, and their influences began to play a bigger role in both their lives, although Shelley did not take drugs. Already a regular pot smoker, Lou dropped acid for the first time and started experimenting with peyote. Taking drugs was not the norm on college campuses in 1961. Though pot was showing up more regularly in fraternities, and a few adventurous students were taking LSD, most students were clean-cut products of the 1950s, preparing for jobs as accountants, lawyers, doctors, and teachers. To them, Lou’s habits and demeanor were extreme. And now, not only was Lou taking drugs, he began selling them to the fraternity boys. Lou kept a stash of pot in a grocery bag in the dorm room of a female friend. Whenever he had a customer, he’d send Shelley to go get it.

Lou was by now on his way to becoming an omnivorous drug user and, apart from taking acid and peyote, would at times buy a codeine-laced cough syrup called turpenhydrate. Lou was stoned a lot of the time. “He liked me to be there when he was high,” Shelley remembered. “He used to say, ‘If I don’t feel good, you’ll take care of me.’ Mostly he took drugs to numb himself or get relief, to take a break from his brain.”

Meanwhile, having presented himself as a born-again heterosexual, Lou now wasted no time in making another shocking move by shoring up his homosexual credentials. In the second semester of his sophomore year, he had what he later described as his first, albeit unconsummated, gay love affair. “It was just the most amazing experience,” Lou explained. “I felt very bad about it because I had a girlfriend and I was always going out on the side, and subterfuge is not my hard-on.” He particularly remembered the pain of “trying to make yourself feel something towards women when you can’t. I couldn’t figure out what was wrong. I wanted to fix it up and make it okay. I figured if I sat around and thought about it, I could straighten it out.”

Lou and Shelley’s relationship rapidly escalated to a high level of game playing. Lou had more than one gay affair at Syracuse and would often try to shock her by casually mentioning that he was attracted to some guy. Shelley, however, could always turn the tables on him because she wasn’t threatened by Lou’s gay affairs and often turned them into competitions that she usually won for the subject’s attentions. If Shelley was a match for Lou, Lou was always ready to up the stakes. They soon got out of their depth playing these and other equally dangerous mind games, which led them into more complexities than they could handle.

Friends had conflicting memories of Lou’s gay life at Syracuse. Allen Hyman viewed him as being extraordinarily heterosexual right through college, whereas Sterling Morrison, who thought Lou was mostly a voyeur, commented, “He tried the gay scene at Syracuse, which was really repellent. He had a little fling with some really flabby, effete fairy. I said, ‘Oh, man, Lou, if you want to do it, I hate to say it but let’s find somebody attractive at least.’”

Homosexuality was generally presented as an unspeakable vice in the early 1960s. Nothing could have been considered more distasteful in 1962 America than the image of two men kissing. The average American would not allow a homosexual in his house for fear he might leave some kind of terrible disease on the toilet seat, or for that matter, the armchair. There were instances reported at universities in America during this time when healthy young men fainted, like Victorian ladies, at the physical approach of a homosexual. In fact, as Andy Warhol would soon prove, at the beginning of the 1960s the homosexual was considered the single most threatening, subversive character in the culture. According to Frank O’Hara’s biographer, Brad Gooch, “A campaign to control gay bars in New York had already begun in January 1964 when the Fawn in Greenwich Village was closed by the police. Reacting to this closing by police department undercover agents, known as ‘actors,’ the New York Times ran a front-page story headlined, ‘Growth of Overt Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Concern.’” Besides the refuge large cities such as San Francisco and New York provided for homosexuals, many cultural institutions, especially the private universities, became home to a large segment of the homosexual community. Syracuse University, where there was a hotbed of homosexual activity, led by Lou’s favorite drama teacher, was no exception.

“As an actor, I couldn’t cut the mustard, as they say,” Reed recalled. “But I was good as a director.” For one project, Lou chose to direct The Car Cemetery (or the Automobile Graveyard) by Fernando Arrabal. Reed could scarcely have found a more appropriate form (the theater of the absurd) or subject (it was loosely based on the Christ mythology) as a reflection of his life. The story line followed an inspired musician to his ultimate betrayal to the secret police by his accompanist. Everything Lou wrote or did was about himself, and had the props been available, perhaps Reed would have considered a climactic electroshock torture scene. In giving the musician a messianic role against a backdrop of cruel sex and prostitution, the play appealed to the would-be writer-musician. “I’m sure Lou had a homosexual experience with his drama teacher,” attested another friend. “This drama teacher used to have guys go up to his room and put on girls’ underwear and take pictures of them and then he’d give you an A. One dean of men himself either committed suicide or left because he was associated with this group of faculty fags who were later indicted for doing all kinds of strange stuff with the students.”

The “first” gay flirtation cannot simply be overlooked and put aside as Morrison and Albin would want it to be. First of all, it had happened before. Back in Freeport during Lou’s childhood, he had indulged in circle jerks, and the gay experience left him with traits that he would develop to his advantage commercially in the near future. Foremost among them was an effeminate walk, with small, carefully taken steps that could identify him from a block away.

Despite an apparent desire originally to concentrate on a career as a writer, just as his guitar was never far from his hand, music was never far from Reed’s thoughts. Lou’s first band at Syracuse was a loosely formed folk group comprising Reed; John Gaines, a striking, tall black guy with a powerful baritone; Joe Annus, a remarkably handsome, big white guy with an equally good voice; and a great banjo player with a big Afro hairdo who looked like Art Garfunkel.

The group often played on a square of grass in the center of campus at the corner of Marshall Street and South Crouse. They also occasionally got jobs at a small bar called the Clam Shack. Lou didn’t like to sing in public because he felt uncomfortable with his voice, but he would sing his own folk songs privately to Shelley. He also played some traditional Scottish ballads based on poems by Robert Burns or Sir Walter Scott. Shelley, who would inspire Lou to write a number of great songs, was deeply moved by the beauty of his music. For her, his chord progressions were just as hypnotic and seductive as his voice. She was often moved to tears by their sensitivity.

Though he was devoting himself to poetry and folk songs, Lou had not dropped his initial ambition to be a rock-and-roll star. In addition to how to direct a play, Lou also learned how to dramatize himself at every opportunity. The showmanship would come in handy when Lou hit the stage with his rock music. Reed’s development of folk music was put in the shade in his sophomore year when he finally formed his first bona fide rock-and-roll band, LA and the Eldorados. LA stood for Lewis and Allen, since Reed and Hyman were the founding members. Lou played rhythm and took the vocals, Allen was on drums, another Sammie, Richard Mishkin, was on piano and bass, and Mishkin brought in Bobby Newman on saxophone. A friend of Lou’s, Stephen Windheim, rounded out the band on lead guitar. They all got along well except for Newman, a loud, obnoxious character from the Bronx who, according to Mishkin, “didn’t give a shit about anyone.” Lou hated Bobby and was greatly relieved when he left school that semester and was replaced by another sax player, Bernie Kroll, whom Lou fondly referred to as “Kroll the troll.”

Reed playing in his Syracuse college band, LA and the Eldorados, with (left) Richard Mishkin. (Victor Bockris)

There was money to be made in the burgeoning Syracuse music scene, and the Eldorados were soon being handled by two students, Donald Schupak, who managed them, and Joe Divoli, who got them local bookings. “I had met Lou when we were freshmen,” Schupak explained. “Maybe because we were friends as freshmen, nothing developed into a problem because he could say, ‘Hey, Schupak, that’s a fucking stupid idea.’ And I’d say, ‘You’re right.’” Soon, under Schupak’s guidance and Reed’s leadership, LA and the Eldorados were working most weekends, playing frat parties, dances, bars, and clubs, making $125 a night, two or three nights a week.

Lou was strongly drawn to the musician’s lifestyle and haunts. Just off campus was the black section of Syracuse, the Fifteenth Ward. There he frequented a dive called the 800 Club, where black musicians and singers performed and jammed together. Lou and his band were accepted there and would occasionally work with some of the singers from a group called the Three Screaming Niggers. “The Three Screaming Niggers were a group of black guys that floated around the upstate campuses,” said Mishkin. “And we would pretend we were them when we got these three black guys to sing. So we would go down there once in a while and play. The people down there always had the attitude, the white man can’t play the blues, and we’d be down playing the blues. Then they’d be nice to us.” The Eldorados also sometimes played with a number of black female backing vocalists.

However, at first what made LA and the Eldorados stick out more than anything else was their car. Mishkin had a 1959 Chrysler New Yorker with gigantic fins, red guitars with flames shooting out of them painted on the side of the car, and “LA and the Eldorados” on the trunk. Simultaneously they all bought vests with gold lamé piping, jeans, boots, and matching shirts. Togged out in lounge-lizard punk and with Mishkin’s gilded chariot to transport them to their shows, the band was a sight when it hit the road. They had the kind of adventures that bond musicians.

Mishkin remembered, “One time we played Colgate and we were driving back in Allen’s Cadillac in the middle of a snowstorm, which eventually stopped us dead. So we’re sitting in the car smoking pot around 1 a.m., and we realized that we can’t do that all night because we’d die. The snow was deep, so we got out of the car and schlepped to this tiny town maybe half a mile away. We needed a place to stay so we went to the local hotel, which was, of course, full. But they had a bar there. Schupak was in the bar telling these stories about how he was in the army in the war, and Lewis and I are hysterical, we are dying it was so funny. Then the bartender said, ‘You can’t stay here, I have to close the bar.’ We ended up going to the courthouse and sleeping in jail.”

The Eldorados further distinguished themselves by mixing some of Lou’s original material into their set of standard Chuck Berry covers. One of Lou’s songs they played a lot was a love song he wrote for Shelley, an early draft of “Coney Island Baby.” “We did a thing called ‘Fuck Around Blues,’” Mishkin recalled. “It was an insult song. It sometimes went over well and it sometimes got us thrown out of fraternity parties.”

LA and the Eldorados played a big part in Lou’s life, providing him with many basic rock experiences, but he kept the band separate from the rest of his life at Syracuse. At first Lou wanted to make a point of being a writer more than a rock-and-roller. In those days, before the Beatles arrived, the term rock-and-roller was something of a put-down associated more with Paul Anka and Pat Boone than the Rolling Stones. Lou preferred to be associated with writers like Jack Kerouac. This dichotomy was spelled out in his limited wardrobe. Like the classic beatnik, Lou usually wore black jeans and T-shirts or turtlenecks, but he also kept a tweed jacket with elbow patches in his closet in case he wanted to come on like John Updike. However, in either role—as rocker or writer—Lou appeared somewhat uncomfortable. Therefore, in each role he used confrontation as a means both to achieve an effect and dramatize an inner turmoil that was quite real. For Hyman and others, this sometimes made working with Lou exceedingly difficult.

According to Allen, “One of the biggest problems we had was that if Lou woke up on the day of the job and he decided he didn’t want to be there, he wouldn’t come. We’d be all set up and looking for him. I remember one fraternity party, it was an afternoon job, we were all set up and ready to go and he just wasn’t there. I ran down to his room and walked through about four hundred pounds of his favorite pistachio nuts, and then I found him in bed under about six hundred pounds of pistachio nuts—in the middle of the afternoon. I looked at him and said, ‘What are you doing? We have a job!’ And he said, ‘Fuck you, get out of here. I don’t want to work today.’ I said, ‘You can’t do this, we’re getting paid!’ Mishkin and I physically dragged him up to the show. Ultimately he did play, but he was very pissed off.”

Reed seemed to at once want the spotlight and to hate it.

“Lou’s uniqueness and stubbornness made him really different than anyone I had ever known,” added Mishkin. “He was a terrible guy to work with. He was impossible. He was always late, he would always find fault with everything that the people who had hired us expected of us. And we were always dragging him here and dragging him there. Sometimes we were called Pasha and the Prophets because Lou was such a son of a bitch at so many gigs he’d upset everyone so much we couldn’t get a gig in those places again. He was as ornery as you can get. People wouldn’t let us back because he was so absolutely rude to people and just so mean and unappreciative of the fact that these people were paying us to get up and play music for them. He couldn’t have cared less. So we used the name Pasha and the Prophets in order to play there again. And then the people who hired us were so drunk they wouldn’t remember. He would never dress or act in a way so that people would accept him. He would often act in a confrontational manner. He wanted to be different.

“But Lou was ambitious. He wanted to be—and said this to me in no uncertain terms—a rock-and-roll star and a writer.”

***