По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

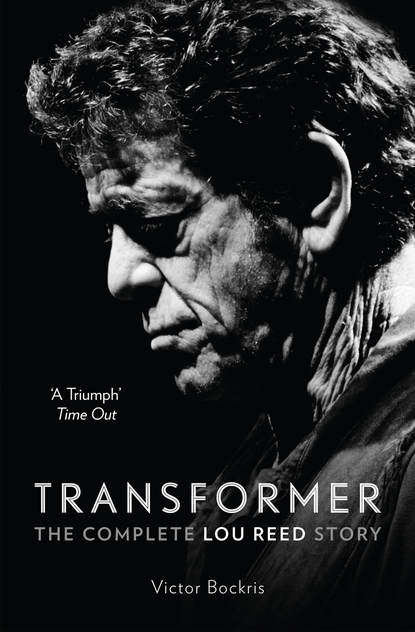

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Providentially, he was aided in his cause by a real illness that struck a few days after he got home to Freeport. Feeling feverish and exhausted, he was diagnosed as having a bad case of hepatitis, which he later claimed to have acquired in a shooting gallery by sharing a needle with a mashed-faced Negro named Jaw. Upon receiving this news, Lou immediately placed an expensive long-distance phone call to Shelley, warning her that she too might have acquired the disease during their recent rapprochement. Then he set about lining up medical evidence sufficient to stave off his recruitment into the army.

According to Lou, he managed to pull off his feat in a record ten minutes by walking into his local draft board chewing on his favorite downer, a 750-milligram Placidyl, a large green pill prescribed for its hypnotic, calming effects and to induce sleep. The effects of the pill come on within fifteen minutes to an hour and may be greatly enhanced when combined with alcohol, barbiturates, and or other central nervous system depressants. Although Placidyl was available over the counter through the 1960s, due to its potential to cause severe, often suicidal depression, as well as drug dependence, it is now available in America by prescription only. “I said I wanted a gun and would shoot anyone or anything in front of me,” Reed recalled. If this smart-aleck claim didn’t do the trick, the yellow pall cast over his visage by the incipient hepatitis did. “I was pronounced mentally unfit and given a classification that meant I’d only be called up if we went to war with China. It was the one thing my shock treatments were good for.”

It was the summer of 1964. His father offered him a job in his tax accountancy business, which he insisted Lou take over and inherit upon his retirement. Lou did not fancy sitting behind a desk peering at a calculator. He told Sidney that he should give his business to Elizabeth (aged sixteen) because she had a better head for such things. Instead, Lou put together a band and hacked his way through the summer playing local shows, which included, as often as possible, gay bars. Resenting his family’s earlier embrace of electroshock treatments and their current disapproval of his lifestyle, Lou set about stinging them with rejection. As he would sing in one of his catalogs of contempt, “Families,” that families who dwell in the suburbs often reduce each other to tears.

However, the battle was not over. Summer fun was one thing allowed the indolent rich graduates on the island, but come fall, every one of them was expected to take up a calling. Hyman was already in law school. Lou’s parents presumed their son would also buckle down to some kind of acceptable career.

How wrong they were! In a move calculated to upset both Delmore Schwartz and his parents, Lou took a job writing made-to-order pop songs for a cheap recording company called Pickwick International and, in their eyes, threw away an expensive education.

The agent of this first step on Lou’s path to becoming a songwriter was none other than Lou’s old friend from Syracuse, the manager of LA and the Eldorados, Don Schupak. “I introduced Lou to a guy who I had developed a partnership with back here in the city, Terry Phillips,” Schupak recalled. Phillips, who had roomed with the record-producing genius Phil Spector in the early 1960s, had convinced Pickwick to venture into the rock business. “They were taught the notion of rock and roll by Terry Phillips and me,” Schupak continued. “They eventually became Musicland, and the people we had to convince to start this studio at the cost of eighty dollars have made tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars in the rock-and-roll business since then.”

Reed was hired on Schupak’s recommendation. “Pickwick started Lou’s career,” Donald recalled. “It taught him the discipline of showing up. It put him into the industry.”

The grand, British-sounding Pickwick International consisted, in fact, of a squat cinder-block warehouse in Long Island City, across the river from Manhattan. The whole operation was run out of this warehouse full of cheap, slapdash records, with a small basement recording studio in a converted storeroom containing, as Schupak, who also worked there as a “record executive,” recalled, “a shitty old spinet piano and a Roberts tape recorder.” Lou, who received $25 a week for his endeavors—and no rights to any of his material—made the twenty-five-minute commute from Freeport to Long Island City every day. Once there, he would find himself locked into the tiny studio with three collaborators: the pasty-faced Phillips, whose pencil mustache, slicked-back hair, and polyester suits evinced his weird distance from life, and two other songwriters, Jerry Vance (alias Jerry Pellegrino) and Jimmie Sims (Jim Smith). While Schupak tried to figure out what he was supposed to be doing, Phillips took it upon himself to direct the fledgling rock arm of the Pickwick label.

Pickwick specialized in producing bargain-basement rip-off albums for a naive mass audience. For example, something like Bobby Darin Sings the Blues featured Darin crooning on exactly one song, squeezed in amidst ten other sung by Jack Borgheimer; the album of ten hot-rod songs by the Roughnecks sported a cover (minus Lou) of four gallivanting lads who looked, at a distance, suspiciously like the Beatles, but were in fact a bunch of pasty-faced session musicians wearing wigs. In other words, the album would say it featured four groups but it wouldn’t really be four groups, it would just be various permutations of the writers, and they would sell them at supermarkets for ninety-nine cents or a dollar. In retrospect, observed Phil Milstein, one of Lou’s most informed and appreciative critics and the founder in 1978 of the Velvet Underground Appreciation Society, “in many ways this is the craziest part of the entire crazy story. No work Lou has done is so trivial, so prefabricated, so tossed off, as what he did at Pickwick.”

The Roughnecks’ song “You’re Driving Me Insane” opened with a tuneless buzz of guitars and then applied the unschooled, scratchy sound of the Kinks to some riffs refined from Chuck Berry. Over the dense, muddy instrumental came the lyrics—half-spoken, half-forced—droned-out words that were supported by the eerie abandon of a rabble of party goers in the background: “The way you rattle your brain / You know you’re driving me insane.” Another contribution by another fake group, the Beachnuts’ “Cycle Annie,” with lyrics by Lou, mixed the surf sound with the first hints of the Velvet Underground. The song allowed Reed to assert himself lyrically with a tale of “a real tough chick” who “just didn’t come any meaner.” Filled with Reedian characters and his playful love of three-chord rock and roll, “Cycle Annie” would have fitted just as well on Loaded.

Lou and his fellow songwriters wrote as fast as they could. Although the setup lacked the glamour of the rock-and-roll lifestyle, it had redeeming educational value. “There were four of us literally locked in a room writing songs,” Reed recounted. “We just churned out songs, that’s all. They would say, ‘Write ten California songs, ten Detroit songs,’ then we’d go down into the studio for an hour or two and cut three or four albums really quickly, which came in handy later because I knew my way around a studio, not well enough but I could work really fast. While I was doing that, I was doing my own stuff and trying to get by, but the material I was doing, people wouldn’t go near me with it at the time. I mean, we wrote ‘Johnny Can’t Surf No More’ and ‘Let the Wedding Bells Ring’ and ‘Hot Rod Song.’ I didn’t see it as schizophrenic at all. I just had a job as a songwriter. I mean, a real hack job. They’d come in and give me a subject, and we’d write.

“I really liked doing it, it was really fun, but I wasn’t doing the stuff I wanted to do. I was just hoping I could somehow get an in, which, in fact, worked out. It’s just worked out in an odd way. But, at least it was something to do with music.”

Naturally, Lou told friends that he hated working at Pickwick and expressed endless bitterness over Phillips’s failure to see any merit in Reed’s own compositions. “I’d say, why don’t we record these?” remembered Reed. “And they’d say ‘No, we can’t record stuff like that.’” (One can only wonder how Johnny Don’t Shoot No More, Ten Drug Songs would have gone over in that halcyon era.) But the truth is that the detached observer in Lou was making out like a bandit in this situation. In fact, he should have been paying them for the very useful education in how to use a recording studio and work with helpful collaborators for whom he would in time come to realize a strong need. Never was he more prolific than during his Pickwick days. Over the course of a few months Reed and his three collaborators published at least fifteen songs. The five months he spent at Pickwick from September 1964 to February 1965 provided the best on-the-job training he could possibly have had for a career in rock and roll.

Chapter Five

The Formation of the Velvet Underground (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

ON THE LOWER EAST SIDE: 1965

The best things come, as a general thing, from the talents that are members of a group; every man works better when he has companions working in the same line, and yielding to stimulus and suggestion, comparison, emulation.

Henry James

It was through Pickwick that Lou met the man who would be the single most important long-lasting collaborator in his life, John Cale. One day in January 1965, Lou, who had not let hepatitis slow him down, had ingested a copious quantity of drugs. As he felt the rush of creativity coming on, he leafed through Eugenia Sheperd’s column in a local tabloid and came across an item about ostrich feathers being the latest fashion craze. Flinging down the paper and grabbing his guitar with the manic pent-up humor that fueled so much of his work, Lou spontaneously created a new would-be dance craze in a song called “The Ostrich.” It joyously told the dancer to put his head on the floor and let his partner step on it. What better self-image could Lou have possibly come up with than this nutty notion, except that the dancers give each other electroshocks?

Although it appeared unlikely that even rock-crazed teenagers, currently dancing the twist and the frug, would go for this masochistic idea, Shupak’s partner, Terry Phillips, desperate for a hit to exonerate his claim that the wave of the future was in rock, immediately snapped that this could be the hit single they had been looking for. With his spacey head full of images of millions of kids across America stomping on each other’s head (he was ten years ahead of his time), the ersatz Andrew Oldham (the Rolling Stones’ equally young and inexperienced producer) got the rock executives out in the warehouse to agree to his proposal that they release “The Ostrich” as a single by a make-believe band called the Primitives. When the record came out, they received a call from a TV dance show, much to their surprise, requesting a performance of “The Ostrich” by “the band.” Eager to promote his project, Phillips persuaded the Pickwick people to let him put together a real band to fill the bill. He saw the pleasingly pubescent-looking Lewis as a natural for lead singer. But he was less than enthusiastic about the other musicians, who did not have the requisite look to con the teen market into spending their spare dollars on “The Ostrich.” Frantic to get the show on the road, Phillips began to search for a backup band for Lou Reed.

From the Pickwick studio the story cuts to Terry Phillips at an Upper East Side Manhattan apartment jammed with a bunch of pasty-faced party people all yukking it up and trying to be cool despite having no idea at all about anything. Ensconced among them, highly amused and somewhat above it all, were the unlikely duo of a big-boned Welshman with a sonorous voice named John Cale and his partner and flatmate, the classic nervy-looking underground man Tony Conrad. In their early twenties and sporting hair unfashionably long for those days, Cale was a classical-music scholar, Conrad an underground filmmaker, and they were both members of one of the midsixties most avant-garde music groups in the world, La Monte Young’s Theater of Eternal Music. On the trail of female companions and good times, they had been brought to the party by the brother of the playwright Jack Gelber, who had recently written a famous play about heroin called The Connection. Spotting these reasonably attractive and slightly eccentric-looking guys with long hair, Terry Phillips immediately asked them if they were musicians. Receiving an affirmative response, he took it for granted that they played guitars (in fact Cale played an electrically amplified viola as well as several Indian instruments) and snapped, “Where’s the drummer?”

The two underground artists, who took their work highly seriously, went along with Phillips as a kind of joke, claiming they did have a drummer so as not to jeopardize the opportunity to make some pocket money. The next day, along with their good friend Walter De Maria, who would soon emerge as one of the leading avant-garde sculptors in the world and was doing a little drumming on the side, they showed up at Pickwick studios as instructed.

Cale, Conrad, and De Maria were highly amused by the bogus setup at Pickwick. To them, the Pickwick executives in polyester suits, who suspiciously pressed contracts into their hands, were hilarious caricatures of rock moguls. On close inspection, as Conrad recalled, the contracts stipulated that they would sign away the rights to everything they did for the rest of their lives in exchange for nothing. After brushing aside this attempt to extract an allegiance more closely resembling indentured servitude than business management, Conrad, Cale, and De Maria were introduced to Lou Reed. He assured them that it would take no time at all to learn their parts to “The Ostrich” since all the guitar strings were tuned to a single note. This information left John Cale and Tony Conrad openmouthed in astonishment since that was exactly what they had been doing at La Monte Young’s rigorous eight-hours-a-day rehearsals. They realized Lou had some kind of innate musical genius that even the salesmen at the studio had picked up on. Tony got the impression that “Lou had a close relationship with these people at Pickwick because they recognized that he was a very gifted person. He impressed everybody as having some particularly assertive personal quality.”

Cale, Conrad, and De Maria agreed to join “The Primitives” and play shows to promote the record on the East Coast. It was primarily a camp lark, but it would also give them a glimpse into the world of commercial rock and roll, in which they were not entirely uninterested.

And so it came about that in their first appearance together, Lou Reed and John Cale found themselves, without prior rehearsal, running onto the stage of some high school in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley following a bellowed introduction: “And here they are from New York—The Primitives!” Confronting a barrage of screaming kids, the band launched into “The Ostrich.” At the end of the song the deejay screamed, rather portentously, “These guys have really got something. I hope it’s not catching!”

Far from being catching, “The Ostrich” died a quick death. After racing around the countryside in a station wagon for several weekends getting a taste of the reality of the rock life without roadies, the band packed it in. Terry Phillips and the Pickwick executives ruefully left off their dream of seeing “The Ostrich” sail into the hemisphere of the charts and returned to the dependable work of Jack Borgheimer.

The attempted breakout had its repercussions though, primarily in introducing Lou to John, who held the keys to a whole other musical universe. The fact was that Lou, like many creative people, had a low threshold for boredom and realized that Terry Phillips’s vision was too narrow to allow him to grow.

***

When Lou started to visit John Cale in his bohemian slum dwelling at 56 Ludlow Street in the deepest bowels of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Reed knew nothing of La Monte Young, or his Theater of Eternal Music, and had little sense of the world he was entering. In keeping with the egocentric personalities he had been cultivating since his successes on the Syracuse University poetry, music, and bohemian scenes, Lou was out for his own ends and at first showed little interest in whatever it was that John was into. Instead, the rock-and-roller set about seducing the classicist.

Cale, for his part, was taken by Reed’s rock-and-roll persona and what little he had witnessed of his spontaneous composition of lyrics, but took a somewhat snooty view of Reed’s initial attempts to strike up a collaborative friendship. “He was trying to get a band together,” Cale said. “I didn’t want to hear his songs. They seemed sorry for themselves. He’d written ‘Heroin’ already, and ‘I’m Waiting for My Man,’ but they wouldn’t let him record it, they didn’t want to do anything with it. I wasn’t really interested—most of the music being written then was folk, and he played his songs with an acoustic guitar—so I didn’t really pay attention because I couldn’t give a shit about folk music. I hated Joan Baez and Dylan. Every song was a fucking question!”

Despite having been a musical prodigy and, before the age of twenty-five, studied with some of the greatest avant-garde composers of the century, by 1965 Cale felt his career was going nowhere. “I was going off into never-never land with classical notions of music,” he said, desperate for a new angle from which to approach music. The sentiment was shared by his family, putting additional pressure on him to get a job. Just like Lou’s mother, Mrs. Cale, a schoolteacher in a small Welsh mining village married to a miner, complained that John would never make a living as a musician and should become a doctor or a lawyer.

Like a bullterrier nipping at pants legs, Lou kept after John, feeling intuitively that the Welshman might provide a necessary catalyst for his music. Eventually, Lou got his way and Cale began to take Lou’s lyrics seriously. “He kept pushing them on me,” Cale recalled, “and finally I saw they weren’t the kind of words you’d get Joan Baez singing. They were very different, he was writing about things other people weren’t. These lyrics were very literate, very well expressed, they were tough.”

Once John grasped what Lou was doing—Method acting in song, as he saw it—he glimpsed the possibility of collaborating to create something vibrant and new. He figured that by combining Young’s theories and techniques with Lou’s lyrical abilities, he could blow himself out of the hole his rigid studies had dug him into. Lou also introduced John to a hallmark of rock-and-roll music—fun—and his youthful enthusiasm was infectious. “We got together and started playing my songs for fun,” Reed recalled. “It was like we were made for each other. He was from the other world of music and he fitted me perfectly. He would fit things he played right into my world, it was so natural.”

“What I saw in Lou’s musical concept was something akin to my own,” agreed Cale. “There was something more than just a rock side to him too. I recognized a tremendous literary quality about his songs which fascinated me—he had a very careful ear, he was very cautious with his words. I had no real knowledge of rock music at that time, so I focused on the literary aspect more.” Cale was so turned on by the connection he started weaning Reed away from Pickwick.

Cale immediately got to work with Reed on orchestrations for the songs. The two men labored over the pieces, each feeding off the fresh ideas of his counterpart. “Lou’s an excellent guitar player,” Cale said. “He’s nuts. It has more to do with the spirit of what he’s doing than playing. And he had this great facility with words, he could improvise songs, which was great. Lyrics and melodies. Take a chord change and just do it.” Cale was an equally exciting player. Unaware of any rock-and-roll models to emulate, he answered Reed’s sonic attacks with illogical, inverted bass lines or his searing electric viola, which sounded, he said, “like a jet engine!”

Meanwhile, as he got to know Lou, and Reed began to unwrap the elements of his legend, John discovered that they had something else in common, “namely,” Lou would deadpan, “dope.” Reed joked dismissively about their heroin use, commenting that when he and Cale first met, they started playing together “because it was safer than dealing dope,” which Reed was apparently still dabbling in. Whilst fully admitting his involvement with heroin, Lou always insisted, and friends tended to concur, that “I was never a heroin addict. I had a toe in that situation. Enough to see the tunnel, the vortex. That’s how I handled my problems. That’s how I grew up, how I did it, like a couple hundred thousand others. You had to be a gutter rat, seeking it out.”

While rationalizing his drug use, Reed also made it clear that it provided him with a shield necessary for both his life and work: “I take drugs just because in the twentieth century in a technological age, living in the city, there are certain drugs you can take just to keep yourself normal like a caveman. Not just to bring yourself up and down, but to attain equilibrium you need to take certain drugs. They don’t get you high, even, they just get you normal.”

Despite the fact that drug taking was widely accepted, practiced, and even celebrated among the artistic residents of Cale’s Lower East Side community, because it was addictive, dangerous, and could be extremely destructive, heroin had a stigma attached to it that led users to keep it private. Thus Cale and Reed found themselves bonded not only by a musical vision and youthful anarchy, but by the secret society heroin users tend to form. The cozy, intimate feelings the drug can bring on magnified their friendship.

Lou started spending a lot of his spare time at John’s. Before long he was staying there for weeks at a time without bothering to return to his parents’ house in Freeport. Lou had long since become fed up with his parents, avoiding them at all costs, and stopping by their house only when in need of money, food, clean laundry, or to check up on the well-being of his dog. Even his involvement with Pickwick was fading under the spell of the Lower East Side rock-and-roll lifestyle. “Lou was like a rock-and-roll animal and authentically turned everybody on,” recalled Tony Conrad. “He really had a deep fixation on that, and his lifestyle was completely compatible and acclimatized to it.”

Cale’s was a match for Reed’s mercurial personality. Moody and paranoid, he too was easily bored and looking for action. John responded to Lou’s driving energy with equal passion, not only sharing Reed’s musical explosions but also providing a creative atmosphere and spiritual home for him. Conrad saw that Lou “was definitely a liberating force for John, but John was an incredible person too. He was very idealistic, putting himself behind what he was interested in and believed in in a tremendous way. John was moving at a very, very fast pace away from a classical training background through the avant-garde and into performance art then rock.” The relationship between John and Lou grew quickly, and it wasn’t long before they started thinking about Lou’s getting out of Freeport, where he was still living very uncomfortably under the disapproving gaze of his parents. Lou was eager to get something happening. “I took off, so there was more room in the pad, and John invited him to come over and stay where I had been staying,” said Conrad. “Lou moved in, which was great because we got him out of his mother’s place.”

“We had little to say to each other,” Lou said of the deteriorating relationship with his parents. “I had gone and done the most horrifying thing possible in those days—I joined a rock band. And of course I represented something very alien to them.”

The hard edge of the Lower East Side kicked Lou into gear. The neighborhood was the loam, as Allen Ginsberg had said, out of which grew “the apocalyptic sensibility, the interest in mystic art, the marginal leavings, the garbage of society.” As Lou discovered John’s ascetic yet sprawling Lower East Side landscape with its population of what Jack Kerouac described as like-minded bodhisattvas, he found himself walking in the footsteps of Stephen Crane (who had come there straight from Syracuse University at the end of the previous century to write Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and wrote to a friend “the sense of a city is war”), John Dos Passos, e. e. cummings, and, most recently, the beats. Indeed, Reed could have walked straight out of the pages of Ginsberg’s Howl for he too would, like one of the poem’s heroes, “purgatory his torso night after night with dreams, with drugs, with waking nightmares, alcohol and cock and endless balls.” Most importantly, the Ludlow Street inhabitants shared with Lou a communal feeling that society was a prison of the nervous system, and they preferred their individual experience. The gifted among them had enough respect for their personal explorations to put them in their art, just as John and Lou were doing, and make them new. Friends from college who visited him there couldn’t believe Lou was living in these conditions, but among the drug addicts and apocalyptic artists of every kind, Lou found, for the first time in his life, a real mental home.

The funky Ludlow Street had for a long time been host to creative spirits like the underground filmmakers Jack Smith and Piero Heliczer. When Lou moved in, an erratic but inventive Scotsman named Angus MacLise, who often drummed in La Monte’s group, lived in the apartment next door. Cale’s L-shaped flat opened into a kitchen, which housed a rarely used bathtub. Beyond it was a small living room and two bedrooms. The whole place was sparsely furnished, with mattresses on the floor and orange crates that served as furniture and firewood. Bare lightbulbs lit the dark rooms, paint and plaster chipped from the woodwork and the walls. There was no heat or hot water, and the landlord collected the $30 rent with a gun. When it got cold during February to March of 1965, they ran out into the streets, grabbed some wooden crates, and threw them into the fireplace, or often sat hunched over their instruments with carpets wrapped around their shoulders. When the toilet stopped up, they picked up the shit and threw it out the window. For sustenance they cooked big pots of porridge or made humongous vegetable pancakes, eating the same glop day in and day out as if it were fuel.

As he began to work with Cale to transform his stark lyrics into dynamic symphonies, he drew John into his world. John found Lou an intriguing, if at times dangerous, roommate. What they had in common was a fascination with the language of music and the permanent expression of risk. “In Lou, I found somebody who not only had artistic sense and could produce it at the drop of a hat, but also had a real street sense,” John Cale recalled. “I was anxious to learn from him, I’d lived a sheltered life. So, from him, I got a short, sharp education. Lou was exorcising a lot of devils back then, and maybe I was using him to exorcise some of mine.”

Lou maintained a correspondence with Delmore Schwartz that led his mentor to believe that he was still definitely on the path to distilling his essence in words. Lou wrote in one letter in early 1965, just after moving to New York City, “If you’re weak NY has many outlets. I can’t resist peering, probing, sometimes participating, other times going right to the edge before sidestepping. Finding viciousness in yourself and that fantastic killer urge and worse yet having the opportunity presented before you is certainly interesting.”

With John in tow, Lou would befriend a drunk in a bar and then, after drawing him out with friendly conversation, according to Cale, suddenly pop the astonishing question, “Would you like to fuck your mother?” John recalled this side of Lou during his early days at Ludlow Street, commenting, “From the start I thought Lou was amazing, someone I could learn a lot from. He had this astonishing talent as a writer. He was someone who’d been around and was definitely bruised. He was also a lot of fun then, though he had a dangerous streak. He enjoyed walking the plank and he could take situations to extremes you couldn’t even imagine until you’d been there with him. I thought I was fairly reckless until I met Lou. But I’d stop at goading a drunk into getting worse. And that’s where Lou would start.” This kind of behavior got them into some hairy situations, abhorred by Cale—who was not as verbally adroit as Lou and was at times agoraphobic and lived in fear of random violence. “I’m very insecure,” said Cale. “I use cracks on the sidewalk to walk down the street. I’d always walk on the lines. I never take anything but a calculated risk, and I do it because it gives me a sense of identity. Fear is a man’s best friend.”

Money was a constant problem. Although Lou had use of his mother’s car and could return to Freeport whenever he desired, and kept working at Pickwick until September, he had nothing beyond his $25.00 per week. He picked up whatever money he could in doing gigs with John, some of them impromptu. Once, they went up to Harlem to play an audition at a blues club. When the odd-looking couple were turned down by the club management, they went out to play on the sidewalk and raked in a sizable amount of money. “We made more money on the sidewalks than anywhere else,” John recalled.

“We were living together in a thirty-dollar-a-month apartment and we really didn’t have any money,” Lou testified. “We used to eat oatmeal all day and all night and give blood among other things, or pose for these nickel or fifteen-cent tabloids they have every week. And when I posed for them my picture came out and it said I was a sex-maniac killer and that I had killed fourteen children and had tape-recorded it and played it in a barn in Kansas at midnight. And when John’s picture came out in the paper, it said he had killed his lover because his lover was going to marry his sister, and he didn’t want his sister to marry a fag.”

Lou was creating the myth of his own Jewish psychodrama. It had become a custom of Lou’s to sicken people with stories of his shock treatment, drug use, and problems with the law. This was the sort of image-building Reed would, in a search for a personality and voice to call his own, perfect in the coming years, culminating in a series of infamous personas in the 1970s. “At that time Lou was relating to me the horrors of electric-shock therapy, he was on medication,” Cale recounted. “I was really horrified. All his best work came from living with his parents. He told me his mother was some sort of ex-beauty queen and his father was a wealthy accountant. They’d put him in a hospital where he’d received shock treatments as a kid. Apparently he was at Syracuse and was given this compulsory choice to do either gym or ROTC. He claimed he couldn’t do gym because he’d break his neck, and when he did ROTC, he threatened to kill his instructor. Then he put his fist through a window or something, and so he was put in a mental hospital. I don’t know the full story. Every time Lou told me about it he’d change it slightly.”

Lou and John resolved to form a band, orchestrate their material into a performable and recordable body of work, and venture out into the world to unleash their music. “When we first started working together, it was on the basis that we were both interested in the same things,” said Cale. “We both needed a vehicle; Lou needed one to carry out his lyrical ideas and I needed one to carry out my musical ideas. It seemed to be a good idea to put a band together and go up onstage and do it, because everybody else seemed to be playing the same thing over and over. Anybody who had a rock-and-roll band in those days would just do a fixed set. I figured that was one way of getting on everybody’s nerves—to have improvisation going on for any length of time.”