По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

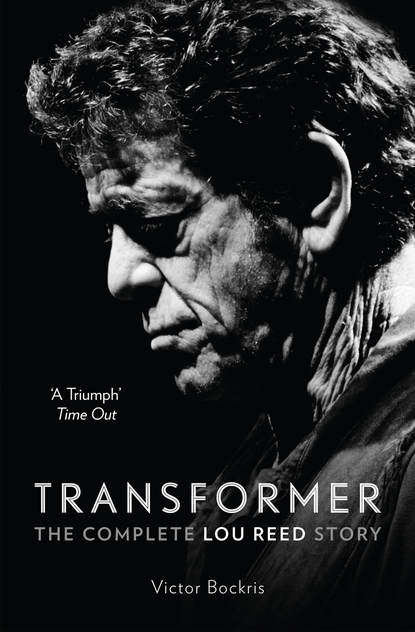

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In May 1962, sick of the stodgy university literary publication and keen to make their mark, Lewis and Lincoln, along with Stoecker, Gaines, Tucker, et al., put out two issues of a literary magazine called the Lonely Woman Quarterly. The title was based on Lou’s favorite Ornette Coleman composition, “Lonely Woman.”

Originating out of the Savoy with the encouragement of Gus Joseph, the first issue contained an untitled story, mentioned in the previous chapter, signed Luis Reed. It described Sidney Reed as a wife-beater, and Toby as a child molester. Shelley, who was involved in the publication, was convinced that just as Lou’s homosexual affair was mostly an attempt to associate with the offbeat gay world, the story was a conspicuous attempt to build his image as an evil, mysterious person. He was smart enough, she thought, to see that this was going to make readers uncomfortable. “And that’s what Lou always wanted to do,” she said, “make people uncomfortable.”

The premier issue of LWQ brought “Luis” his first press mention. In reviewing the magazine, the university’s newspaper, the Daily Orange, had interviewed Lincoln, who boasted that the magazine’s one hundred copies had sold out in three days. Indeed, the first issue was well received, but when everyone else on its staff apparently got lazy, Lou put out issue number two, which featured his second explosive piece, printed on page one. Called “Profile: Michael Kogan—Syracuse’s Miss Blanding,” it was the most attention-grabbing project Lou ever pulled off at Syracuse: a deftly executed, harsh attack upon the student who was head of the Young Democrats Party at the University. Allen Hyman recalled, “It said something like he [Kogan] should parade around campus with an American flag up his ass, which at the time was a fairly outrageous statement.” Unfortunately, Kogan’s father turned out to be a powerful corporation lawyer. “He decided that the piece was libelous,” remembered Sterling, “and he’d bust Lou’s ass. So they hauled him before the dean. But … the dean started shifting to Lou’s side. Afterwards, the dean told Lou to finish up his work and get his ass out of there, and nothing would happen to him.” By May of 1962, Reed’s literary career was off to a running start.

Despite this, Lou’s relationship with Shelley—not his classes—had dominated his sophomore year. They had spent as many of their waking hours together as was possible, camping out over the weekends in friends’ apartments, using fraternity rooms, cars, and sometimes even bushes to make love. Lou received a D in Introduction to Math and an F in English History. Then he got in trouble with the authorities again when a friend was busted for smoking pot and ratted on a number of people, including Lewis and Ritchie Mishkin.

“We smoked all the time,” admitted Mishkin. “But we didn’t smoke and work. We may have played and then smoked after and then jammed. Anyway, the dean of men called Lou, me, and some other people into his office and said, ‘We know you were smoking pot, so give us the whole story.’ We were terrified, at least I was. But nothing happened. Lou was angry. With the authorities and with the informer. But they were pretty soft on us. We were lucky, but then all they had to go on was the ‘he said, she said’ kind of evidence, so there was a limit to what they could do. But they had us in the office and they did the old, ‘We know because so-and-so said …’”

As a result of these numerous transgressions, and with his apparent academic torpor at the end of his sophomore year, Reed was put on academic probation.

***

The summer of 1962 was somewhat difficult for Lou. This was the first time he had been separated from Shelley for more than a day, and he took it hard. First, in an attempt to exert his control over her across the thousand miles that separated them, he embarked on a zealous letter-writing campaign, sending her long, storylike letters every day. They would begin with an account of his daily routine—he would go to the local gay bar, the Hayloft, every night—and tweak Shelley with suggestive comments. Then, in the middle of a paragraph the epistle would abruptly shift from reality to fiction and Lou would take off on one of his short stories, usually mirroring his passion and longing for Shelley. An exemplary story sent across the country that summer was “The Gift,” which appeared on the Velvet Underground’s second album, White Light/White Heat, and perfectly summed up Lou’s image of himself as a lonely Long Island nerd pining for his promiscuous girlfriend. “The Gift” climaxed with the lovelorn author desperately mailing himself to his lover in a womblike cardboard box. The final image, in the classic style of Yiddish humor that informed so much of Reed’s work, had the boyfriend being accidentally killed by his girlfriend as she opened the box with a large sheet-metal cutter.

Shelley, a classic passive-aggressive character, rarely responded in kind, but she did talk to Lou on the phone several times that summer, and he did not like what he heard at all. Lou had expected Shelley to remain locked in her room thinking of nothing but him. But Shelley wasn’t that kind of girl. Despite having commenced the vacation with a visit to the hospital to have her tonsils out, by July she was platonically dating more than one guy and at least one was madly in love with her. Despite the fact that Shelley was really loyal to Lou, the emotions Lou addressed in “The Gift” were his. He paced up and down his room in frustration. He couldn’t stand not having Shelley under this thumb. It was driving him insane.

Then he hit on a plan. Why not go out and visit her? After all, he was her boyfriend, he was writing to her every day or so and had called her several times. It sounded like the right thing to do. His parents, who had kept a wary eye on their wayward son that summer, still frowning on his naughty visits to the Hayloft and daily excursions on the guitar, were only too happy to support a venture that they felt was taking him in the right direction. At the beginning of August he flew out to Chicago.

Shelley had been adamantly against the planned visit, warning Lou on the phone that her parents wouldn’t like him, that it was a big mistake and wouldn’t work out at all. But Lou, who wanted, she recalled, “to be in front of my face,” insisted.

By now Lou had developed a pattern of reaction to any new environment he entered. His plan was to split up any group, polarizing them around him. In a family situation, as soon as he walked into anybody’s house, he took the position that the father was a tyrannical ogre whom the mother had to be saved from. On his first night in the Albins’ home, he cleverly drew Mr. Albin into a political discussion and then, marking him for the bullheaded liberal Democrat that he was, expertly lanced him with a detailed defense of the notorious conservative columnist William Buckley. While Shelley sat back and watched, half-horrified, half-mesmerized, Mr. Albin became increasingly apoplectic. Lou was obviously not the right man for his daughter. In fact, he didn’t even want him in the house.

The Albins had rented a room for Lou in nearby Evanston, at Northwestern University. Using every trick in his book, Lou pulled a double whammy on Mr. Albin, driving his car into a ditch later the same night when bringing Shelley back from the movies at 1 a.m., forcing her father to get up, get dressed, come out, and help haul out the mauled automobile.

Things went downhill from there. Lou made a valiant attempt to win over Mrs. Albin. Having dinner with her and Shelley one night when the man of the house was absent, Lou launched into his classic rap, saying, “Gee, you’re clearly very nice. If it wasn’t for the ogre living in the house …” But Mrs. Albin was having none of his boyish charm. She had surreptitiously read Lou’s letters to Shelley that summer and formed a very definite opinion about Lou Reed: she hated him with a passion—and still does more than thirty years later. In her opinion, Lou was ruining her daughter’s life.

As an upshot of Lou’s visit, Shelley’s parents informed her that if she continued to see Lou in any way at all, she would never be allowed to return to Syracuse. Naturally, swearing that she would never set eyes upon the rebel again, Shelley now embarked upon a secret relationship with Lou that trapped her exactly where Reed wanted. Since Shelley had no one outside of Lou’s circle in whom she could confide about her relationship with him, she was essentially under his control. From here on Lou would always attempt to program his women. His first move would always be to amputate them from their former lives so that they accepted that the rules were Lou’s.

Chapter Three

Shelley, If You Just Come Back (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: 1962–64

The image of the artist who follows a brilliant leap to success with a fall into misery and squalor, is deeply credited, even cherished in our culture.

Irving Howe, from his foreword to In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories by Delmore Schwartz

When Lou returned to Syracuse for his junior year, he rented a room in a large apartment inhabited by a number of like-minded musicians and English majors on Adams Street. The room was so small that it could barely contain the bed, but that was okay with Lou because he lived in the bed. He had his typewriter, his guitar, and Shelley, who was now living in one of the cottage-style dorms opposite Crouse College, which were far less supervised than the big women’s dorm. She was consequently able to live with Lou pretty much full-time.

The semester began magically with Shelley’s arrival. Lou whipped out his guitar and a new instrument he had mastered over the summer, a harmonica, which he wore in a rack around his neck, and launched into a series of songs he had written for Shelley over the vacation, including the beautiful “I Found a Reason.” Shelley, who was completely seduced by Lou’s music, was brought to tears by the beauty and sensitivity of his playing, the music and the lyrics. Lou played the harmonica with an intense, mournful air that perfectly complemented his songs, but was unfortunately so much like Bob Dylan’s that, so as not to be seen as a Dylan clone, he had to retire the instrument. It was a pity because Lou was a great, expressive harmonica player. In his new pad, he played his music as loud as he wanted and took drugs with impunity. It also became another stage on which to develop “Lou Reed.” He rehearsed with the band there, often played music all night, and maintained a creative working environment essential to his writing. He was really beginning to feel his power. His band was under his control. He had already written “The Gift,” “Coney Island Baby,” “Fuck Around Blues,” and later classics like “I’ll Be Your Mirror” were in the works.

By the mid-1960s, the American college campus was going through a remarkable transformation that would soon introduce it to the world as one of the brighter beacons of politics and art. One of the marks of a particularly hip school was its creative writing department. Few American writers were able to make a living out of writing books. Somewhere in the 1950s some nut put together the bogus notion that you could haul in some bigwig writer like Ernest Hemingway or Samuel Beckett and get him to teach a bunch of some ten to fifteen young people how to write. However, it had succeeded in dragging a series of glamorous superstars like T. S. Eliot (a rival with Einstein and Churchill as the top draw in the 1950s) to Harvard for six weeks to give a series of lectures about how he wrote, leading hundreds of students to write poor imitations of The Waste Land. The concept of the creative writing program looked good on paper, but it was, in reality, a giant shuck, and the (mostly) poets who were on the lucrative gravy train in the early sixties were, for the most part, a bunch of wasted men who had helped popularize the craft during its glorious moment 1920–50, when poets like W. H. Auden had the cachet rock stars would acquire in the second half of the century.

Delmore Schwartz was one of the most charismatic, stunning-looking poets on the circuit. He had been foisted on the Syracuse University creative writing program by two heavyweights in the field—the great poet Robert Lowell and the novelist Saul Bellow, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize—who had known him in his prime as America’s answer to T. S. Eliot. Unfortunately for both him and his students, Schwartz had by then, like so many of his calling, expelled his muse with near-lethal daily doses of amphetamine pills washed down by copious amounts of hard alcohol. Despite having as recently as 1959 won the prestigious Bollingen Prize for his selected poems, Summer Knowledge, when he arrived on campus in September 1962, Schwartz was, in fact, suffering through the saddest and most painful period of his life.

Sporting on his forty-nine-year-old face a greenish yellow tinge, which gave the impression he was suffering from a permanent case of jaundice, and a pair of mad eyes that boiled out from under his big, bloated brow with unrestrained paranoia, on a good day this brilliant man could still hold a class spellbound with the intelligence, sensitivity, and conviction of his hypnotic voice once it had seized upon its religion—literature. Schwartz once received a ten-minute standing ovation at Syracuse after giving his class a moving reading of The Waste Land. Unfortunately, by 1962 his stock was so low that none of the performances he gave at Syracuse—in the street, in the classroom, in bars, in his apartment, at faculty meetings, anywhere his voice could find receivers—was recorded.

Until the arrival of Delmore Schwartz, Lou Reed had not been overly impressed by his instructors at Syracuse. However, Lou only had to encounter Delmore once to realize that he had finally found a man impressively more disturbed than himself, from whom he might be able to get some perspective on all the demons that were boiling in his brain.

If Lou had been looking for a father figure ever since rejecting his old man as a silent, suffering Milquetoast, he had now found a perfect one in Delmore Schwartz. In both Bellow’s novel about Schwartz, Humboldt’s Gift, and James Atlas’s outstanding biography, Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet, many descriptions of Schwartz’s salient characteristics could just as well apply to what Lou Reed was fast becoming.

As Lou already did, Delmore entangled his friends in relationships with unnatural ardor until he was finally unbearable to everyone. Like Lou, Delmore ultimately caused those around him more suffering than pleasure. Like Lou, Delmore possessed a stunning arrogance along with a nature that was as solicitous as it was dictatorial. Both possessed astonishing displays of self-hatred mixed with self-love and finally concluded in concurrence with many of their friends that they were evil beings. Both were wonderful, hectic, nonstop inspirational improvisators and monologuists as well as expert flatterers. Grand, erratic, handsome men, they both gained much of their insights during long nights of insomnia.

But there the comparison ended. For Delmore Schwartz was already singing himself in and out of madness, and when his heart danced, it never danced for joy, whereas Lou possessed a marvelous ability for unadulterated joy and a carefully locked hold on reality. He had no doubt that he was going to succeed, and most of his friends equally believed in his talent. Lou may have shared with Delmore moments of sublime inspiration alternated with moments of indescribable despair, but unlike Schwartz, Reed had not read himself out of American culture.

In his junior year, Reed took a number of courses with Schwartz apart from creative writing. They read Dostoyevsky, Shakespeare, and Joyce together, and when studying Ulysses, Lou saw himself as Dedalus to Schwartz’s Bloom. They developed a friendship that would go on until Lou graduated.

At first Schwartz would attend classes in which it was his duty to entertain students. Soon, however, rather than attempting to teach them how to write, he would fall into wandering, often despondent rants about the great men he had known, the sex life of the queen of England, etc., conveying his information in tones so authoritative and confiding that he convinced his astonished audiences that he really knew what he was talking about. When he grew tired of these exercises of nostalgia for a lost life, he would often fill in the time reading aloud or, on bad days, mumbling incoherently. He also set up an office at the far back left-hand corner table of the Orange Bar, where, usually sitting directly opposite Lou, who was one of the few students able to respond to him, and surrounded by several rows of chairs, Schwartz would do what he had now become best at. Saul Bellow called him “the Mozart of conversation.”

Shelley, who was always at the table with them, recalled that Lou and Delmore “adored each other. Delmore was always drinking, popping Valiums, and talking. He was kind of edgy, big, he would move but in a very contained manner. His hands would move, picking things up, putting them down; he was always lurking over and I always got the feeling he was slobbering because he was always eating and talking and spitting things out. He was very direct to me. He said, ‘I love Lou. You have to take care of Lou because he has to be a writer. He is a writer. And it is your job to give up your life to make sure that Lou becomes a writer. Don’t let him treat you like shit. But tolerate everything he does to stay with him because he needs you.’”

Later in his life, perhaps to some extent to disarm the notion that he was just a rock-and-roll guitar player, Lou liked nothing better than to reminisce about his relationship with Delmore. “Delmore was my teacher, my friend, and the man who changed my life. He was the smartest, funniest, saddest person I had ever met. I studied with him in the bar. Actually, it was him talking and me listening. People who knew me would say, ‘I can’t imagine that.’ But that’s what it was. I just thought Delmore was the greatest. We drank together starting at eight in the morning. He was an awesome person. He’d order five drinks at once. He was incredibly smart. He could recite the encyclopedia to you starting with the letter A. He was also one of the funniest people I ever met in my life. He was an amazingly articulate, funny raconteur of the ages. At this time Delmore would be reading Finnegans Wake out loud, which seemed like the only way I could get through it. Delmore thought you could do worse with your life than devote it to reading James Joyce. He was very intellectual but very funny. And he hated pop music. He would start screaming at people in the bar to turn the jukebox off.

“At the time, no matter how strange the stories or the requests or the plan, I was there. I was ready to go for him. He was incredible, even in his decline. I’d never met anybody like him. I wanted to write a novel; I took creative writing. At the same time, I was in rock-and-roll bands. It doesn’t take a great leap to say, ‘Gee, why don’t I put the two together?’”

Schwartz’s most famous story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” was a real eye-opener for Lou. The story centers around a hallucination by a son who finds himself in a cinema watching a documentary about his parents and flips out, screaming a warning to them not to have a son. “‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities’ really was amazing to me,” Lou recalled. “To think you could do that with the simplest words available in such a short span of pages and create something so incredibly powerful. You could write something like that and not have the greatest vocabulary in the world. I wanted to write that way, simple words to cause an emotion, and put them with my three chords.”

Delmore, for his part, clearly believed in Lou as a writer. The climax of Lou’s relationship with Delmore came when the older poet put his arm around Lou in the Orange Bar one night and told him, “I’m gonna be leaving for a world far better than this soon, but I want you to know that if you ever sell out and go work for Madison Avenue or write junk, I will haunt you.”

“I hadn’t thought about doing anything, let alone selling out,” Reed recalled. “I took that seriously. He saw even then that I was capable of writing decently. Because I never showed him anything I wrote—I was really afraid. But he thought that much of me. That was a tremendous compliment to me, and I always retained that.”

Close though they were, they had two serious differences of opinion. As a man of the forties, Delmore was an educated hater of homosexuals. The uncomprehending attitudes common among straight American males toward gays in the early sixties put homosexuals on the level of communists or drug addicts. Therefore, Lou was unable to show Delmore many of his best short stories, since they were based on gay themes.

Then there was rock and roll. Delmore despised it, and in particular the lyrics, which he saw as a cancer in the language. Delmore knew Lou was in a band but wrote it off as a childish activity he would outgrow as soon as he commenced his graduate studies in literature.

Delmore Schwartz was thus barred from two of the most powerful strands of Lou’s work.

***

Lou’s relationship with Shelley reached its apotheosis in his junior year when, she felt, he really gained in confidence and began to transform himself. Ensconced together in the Adams Street apartment debris of guitars and amps, books, clothing, and cigarettes, Lou now lived in a world of music accompanied by the spirit of Shelley. She knew every nook and cranny of him better than anybody, and before he put his armor on. She had become his best friend, the one who could look into his eyes, the one he wrote for and played to.

Lou needed to be grounded because although Lincoln could be cooler than whipped cream and smarter than amphetamine, he was a lunatic. Lou always needed a court jester nearby to keep him amused, but he also required the presence of a straight, 1950s woman who could cool him down when the visions got too heavy. Shelley Albin became everything to Lou Reed: she was mother, sister, muse, lover, fixer-upper, therapist, drug mule, mad girl. She did everything with Lou twenty-four hours a day.

Lou was drinking at the Orange as Delmore told stories of perverts and weirdos and fulminated over the real or imaginary plots that were afoot in Washington. Lou was flying on a magic carpet of drugs. Pages of manuscripts and other debris piled up in his room, which Shelley felt was a purposeful pigsty. Lou was having an intensely exciting relationship with Lincoln, who was going bonkers, lost in a long, hysterical novel mostly dictated by a series of voices giving him conflicting orders in his head. Lou was also displaying that special nerve that is given to very few men, getting up in front of audiences three or four times a week, blowing off a pretty good set of rock and roll, playing some wild, inventive guitar, becoming a lyrical harmonica player, turning his voice into a human jukebox.

Everything was changing. Rock was “Telstar” by the Tornadoes, “Walk Like a Man” by the Four Seasons, “He’s So Fine” by the Chiffons—all great records in Lou’s mind—but what was really happening on campuses across the USA was folk music. Dylan was about to make his big entrance, beating Lou to the title of poet laureate of his generation.

At this point, Lou appeared to have several options. He could have gone to Harvard under the wing of Delmore Schwartz and perhaps been an important poet. He could have married Shelley and become a folksinger. He could have collaborated with any number of musicians at Syracuse to form a rock-and-roll band. Instead, he began to separate himself from each of his allies and collaborators one by one.

***

The trouble started with Lou’s acquisition of a dog, Seymour, a female cross between a German shepherd and a beagle cum dachshund, three and a half feet long standing four inches off the ground. If you believe that dogs always mirror their owners, then Seymour was, in Shelley’s words, “a Lou dog.” Lou appeared to be able to open up more easily and communicate more sympathetically with Seymour than with anybody else in the vicinity. As far as Shelley could tell, the only times Lou seemed to feel really at peace with himself were when he was rolling on the floor with Seymour, or sitting with the mutt on the couch staring into space. Soon, however, Lou’s love for the dog became obsessive, and he started remonstrating with Shelley about treating Seymour better and paying more attention to her.

Meanwhile, Lou’s behaviour increasingly hinted at the complex nature Shelley would have to deal with if she stayed with him. “I mean he got crazy about being nice to that dog,” she commented later. “He was a total shit about it, so that was a clue.” But then he couldn’t be bothered to take the dog out for a walk in the freezing cold. It soon became evident that it fell to Shelley to feed and walk the dog. Even then the mercurial Lewis decided to dump the dog. Shelley had to persuade him not to. Then Lewis hit on another diabolical plan. He would take the dog home to Freeport and dump it on his family, without warning. And he knew exactly how to do it.

That Thanksgiving, Lou and Shelley returned to Freeport with the surprise gift. Displaying its Lou-like behavior, at La Guardia airport the dog rushed out of the cargo area where it had been forced to travel and immediately pissed all over the floor, leading Lou’s mother to start screaming, “A dog! Oh my God, a dog in my house! We don’t need a dog!” Riposting with the artful aplomb that would lead so many of Reed’s later collaborators to despair, Lou presented an offer that could not be refused, announcing that the dog was, in fact, a gift for Bunny.