По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

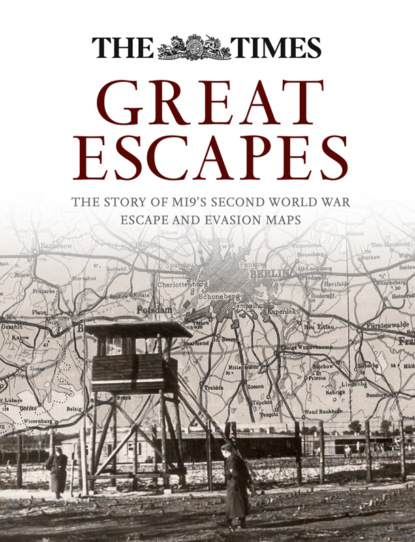

Great Escapes: The story of MI9’s Second World War escape and evasion maps

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It is the intelligent use of geographical knowledge that outwits the enemy and wins wars.’

(W. G. V. Balchin in The Geographical Journal, July 1987)

This book is the culmination of the author’s personal fascination with maps and charts, and especially with military maps on silk. To be given the task, as a young researcher in the Ministry of Defence Map Library over thirty years ago, of identifying MI9’s escape and evasion maps and creating an archival record set of them was a piece of serendipity. That small task ignited an interest which has never been extinguished. It was, however, only after retirement that the opportunity arose to commit to a detailed and more in-depth study of the subject: the reward was the discovery of a story of remarkable cartographic intrigue and ingenuity, and the opportunity to make this small contribution to the history of cartography in the twentieth century.

During the course of World War II, a complex and daring operation was launched by MI9, a newly formed branch of the British intelligence services, to help servicemen evade capture and, for those who were captured, to assist them in escaping from prisoner of war camps across Europe. Ingenious methods were devised to deliver escape and evasion aids to prisoners, and intricate codes were developed to communicate with the camps. In stories that often appear stranger than fiction, such materials proved critical and made many escapes possible. Maps were an integral part of this operation, with maps printed on silk and other fabrics commonly being secreted in innocent-looking items being sent to the camps, for example in playing cards, board games and gramophone records. The role of maps in this operation has often been overlooked and, because of strict instructions to service personnel at the time not to speak about the maps, the story has remained largely untold.

The principal aim of this book is, for the first time, to reconstruct, document and analyse the programme of escape and evasion mapping on which MI9 embarked. Such an exercise has never previously been attempted. The book charts the origins, scope, nature, character and impact of MI9’s escape and evasion mapping programme in the period 1939–45. It traces the development of the mapping programme in the face of many challenges and describes the ways in which MI9 sought to overcome those challenges with the considerable assistance of both individuals and commercial companies. Through a number of examples, the extent to which the mapping programme was the key to the success of the whole of MI9’s escape programme is assessed. The Appendices contain a detailed carto-bibliography, where all the individual maps are identified and described; production details are provided and location information on those surviving copies which have been identified is also provided.

The new intelligence branch was born in December 1939 and was charged with escape and evasion activities to support those who, it was anticipated, would either be shot down in enemy-held territory or would be captured. Its gestation had been lengthy. From the view held prior to World War I that there was something ignominious about capture, the military philosophy had evolved sufficiently in the inter-war period for escape activity to be regarded as a priority in the greater scheme of warfare. The new branch tried to tackle the aftermath of the disaster which befell the Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk in May 1940, but it took time and resources to mount the sort of organization which was needed. By then the nation was led by a new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who had had personal experience of escaping from captivity in the Boer War and was, undoubtedly, a natural ambassador for the changed philosophy. He had been a war correspondent for the Morning Post and was captured by the Boers in November 1899. He escaped on 12 December, and, travelling on foot and by train, he successfully made it across the border to Mozambique and freedom. In his account he noted that he was ‘in the heart of the enemy’s country’ but lacked ‘the compass and the map which might have guided me’.

The story of the mapping programme which became such an important part of MI9’s escape programme has been difficult to piece together. No single, comprehensive record of the production programme has ever been found and the archival record set of the maps is only now (2015) being deposited in The National Archives by the Ministry of Defence. Copies of the maps have been found in many collections, both public and private, throughout the country. There is, however, very little mention of the maps in the published literature and some of the possibly relevant MI9 files in The National Archives are still closed. Reconstructing the story has proved to be like the reassembly of a jigsaw puzzle where some pieces are still missing, possibly lost for all time. Nevertheless, careful enquiry has yielded enough evidence to enable the narrative to be recovered. What emerges is a story of quite amazing inspiration and ingenuity in a country at war, fighting for the survival of its core democratic values and standards.

The intelligence world of the time also needs to be considered. MI9 was a new player in a world where others had already carved out for themselves a sizable role and niche. The part played by MI6, more commonly referred to as SIS (the Secret Intelligence Service), proved to be unhelpful and unsupportive to the newly created branch. The key staff recruited to MI9, especially Christopher Clayton Hutton, who was ultimately responsible for the mapping programme, had some of the skills they needed, but absolutely no cartographic awareness. The dark fog which often surrounded the world of security and espionage meant that key contacts were not made at critical times and there was often a lack of awareness of where the experience and expertise which MI9 so badly needed actually lay.

Producing the maps was one thing, getting them to the prisoners of war was quite another. Just how they were smuggled into the camps, how MI9 communicated with the camps, and how the whole escape programme took shape is part of the unfolding story. The art of smuggling items inside hollowed out containers was used extensively by MI9, who persuaded the manufacturers of board games and other leisure aids to assist them in their endeavours. Coded communication with the camps proved to be the vital link in the chain and deciphering a number of surviving coded letters provided the proof of the importance of that system of communication. The prisoners of war themselves also rose to the challenge. They had been trained that it was their duty to attempt to escape, not least by MI9 itself, which promoted the philosophy of ‘escape-mindedness’ through its Training School. Escape committees were set up in many of the camps, certainly in the oflags (prisoner of war camps for officers). The many hours of the potentially excruciating boredom of captivity were funnelled into escape activity. Escapes were managed as military operations in both the planning and execution. Men used their talents and, in many cases, their professional expertise, to copy maps, to produce compasses and clothing, and to forge papers and passes to aid the escapers on their journey to freedom. Lessons were learned from both the successes and failures, and key experiences were either brought back to the camps by the failed escapers or relayed back to the camps by the successful escapers, for use in future attempts.

The structure of the book reflects the story of the mapping programme as it unfolded. Chapter 1 shows that MI9 was essentially a creation of World War II and it reflected a markedly changed military attitude to capture, escape and evasion. It was staffed with people who had been carefully selected by the head of the fledgling organization. The skills and experiences which they each brought to the task are described and acknowledged, and the development of the organization itself is traced. Chapter 2 looks at the background behind the development of the mapping programme and the long history of military mapping on silk, which was most certainly not prompted simply by a twentieth-century war. Chapter 3 describes in detail the whole map production programme from the individual series, through the printing process to the sourcing of silk, and later, of man-made fibre. The covert nature of the programme and the compartmentalized way in which it was managed by MI9 resulted in their own unique, and arguably unnecessary, challenges. Having documented and analysed both the production programme and the maps themselves, the book continues in Chapter 4 by addressing the whole escape aids programme. The sheer ingenuity and originality of the smuggling programme which MI9 mounted in order to ensure that the maps reached their destinations is addressed. The whole of Chapter 5 is given over to a detailed discussion of the coded correspondence, augmented by the first deciphering of some of the original coded correspondence from a family archive.

A number of escapes were selected as examples to try to prove the value of the maps produced. The first of these, considered in Chapter 6, was based on one of the most successful escape routes which MI9 planned from occupied Europe to the safe haven of neutral Switzerland. Chapter 7 examines escapes via the Baltic ports to neutral Sweden, an even more successful route to freedom, and Chapter 8 studies the ways in which maps were copied in the camps and analyses two surviving maps apparently drawn in prisoner of war camps. Finally, Chapter 9 seeks to offer an objective assessment of the real success of the mapping programme in the light of the many obstacles and challenges which MI9 faced.

Without question, the maps produced by MI9 proved to be the key to successful escape: without them many, perhaps most, of the thousands of men who successfully escaped and made it back to these shores before the end of the war would have failed in their efforts.

The value of printing military maps on fabric has been long recognized. This map, printed on cloth, covers part of northwestern Georgia and adjacent Alabama to the west of Atlanta. It is annotated in blue pencil in the upper margin: ‘Specimen of field maps used in Sherman’s campaigns, 1864’ (see pages 40–41).

1 (#ulink_7321c9fb-67ea-5910-b8a1-b3dda65eed90)

THE CREATION OF MI9 (#ulink_7321c9fb-67ea-5910-b8a1-b3dda65eed90)

‘Escaping and evading are ancient arts of war.’

(Field-Marshal Sir Gerald Templar, in the Foreword to MI9: Escape and Evasion, 1939–1945 by M. R. D. Foot and J. M. Langley)

MI9 was created on 23 December 1939 as a new branch of British intelligence to provide escape and evasion support to captured servicemen and to airmen shot down over enemy-held territory through the course of World War II. Arguably, it was not soon enough, as, less than six months after its creation, thousands of British Service personnel found themselves captured on the beaches at Dunkirk. MI9 was established within the Directorate of Military Intelligence, which came into existence in 1939 when, with the Directorate of Military Operations, it superseded a previously combined Directorate of Military Operations and Intelligence. Five of the Military Intelligence sections, MI1 to MI5, continued their work within the new Directorate, dealing, as before, with organization, geographic, topographic, coded communication and security matters.

The creation of MI9 stemmed from the experience of many during World War I, when military philosophy about prisoners of war underwent a sea-change. From regarding capture and captivity in enemy hands as a somewhat ignominious, even shameful and disgraceful fate, the value that escaping prisoners of war might contribute to the success of the war effort gradually came to be recognized. Men who escaped or evaded capture and returned to Britain brought back vital intelligence and boosted the morale of the Armed Services and, not least, their own families. In addition, the considerable effort required to prevent escapes from the camps deflected the enemy’s resources from front-line combat action.

In the late 1930s, as the prospect of war became increasingly likely, proposals for the creation of a section tasked to look after the interests of British prisoners of war came from many quarters, not least from Lieutenant Colonel (later Field-Marshal) Gerald Templar who had written to the Director of Military Intelligence in September 1939. A number of conferences with those who had been prisoners of war during World War I had also been arranged by MI1, seeking to benefit from their collective experiences. The actual proposal to the Joint Intelligence Committee to create such a branch came from Sir Campbell Stuart, who chaired a War Office Committee looking at the coordination of political intelligence and military operations. There had clearly been some robust discussions, since Viscount Halifax, appointed Foreign Secretary in February 1938 by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, had indicated in a letter dated 5 December 1939 to Sir Campbell that his preference was for the section to be under Foreign Office control, with direct Treasury funding, presumably to ensure joint control and coordination with MI6, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Notwithstanding this high-level opposition, the creation of MI9 went ahead in the War Office and it was made responsible to the Deputy Director for Military Intelligence, initially working closely with the Admiralty and the Air Ministry. With hindsight, the later animosity and conflict between MI9 and SIS (see Chapter 9) might well have had its roots in the initial difference of opinion as to where the newly formed section should sit in the governmental hierarchy.

Three British prisoner of war escapers who tunnelled out of Holzminden prisoner of war camp in Germany during World War I on 23 July 1918. That night twenty-nine men made good their escape, ten of whom made their way to the neutral Netherlands some 320 kilometres (200 miles) from the camp and eventually back to Britain. Left to right: Captain Caspar Kennard, Major Gray and Lieutenant Blair, all of the Royal Flying Corps.

Sir Campbell Stuart (1885–1972), who made the initial proposal for the creation of MI9 to the Joint Intelligence Committee in 1939.

MI9’s objectives and methods were first outlined in the ‘Conduct of Work No. 48’, issued by the Directorate of Military Intelligence on 23 December 1939. In MI9’s War Diaries (the regular record of daily, weekly or monthly activities undertaken by the War Office branches during the war), its objectives were more fully described as:

i) To facilitate the escape of British prisoners of war, their repatriation to the United Kingdom (UK) and also to contain enemy manpower and resources in guarding the British prisoners of war and seeking to prevent their escape.

ii) To facilitate the return to the UK of those who evaded capture in enemy occupied territory.

iii) To collect and distribute information on escape and evasion, including research into, and the provision of, escape aids either prior to deployment or by covert despatch to prisoners of war.

iv) To instruct service personnel in escape and evasion techniques through preliminary training, the provision of lecturers and Bulletins and to train selected individuals in the use of coded communication through letters.

v) To maintain the morale of British prisoners of war by maintaining contact through correspondence and other means and to engage in the specific planning and execution of evasion and escape.

vi) To collect information from British prisoners of war through maintaining contact with them during captivity and after successful repatriation and disseminate the intelligence obtained to all three Services and appropriate Government Departments.

vii) To advise on counter-escape measures for German prisoners of war in Great Britain.

viii) To deny related information to the enemy.

The original Conduct of Work No. 48 for MI9, produced by the Directorate of Military intelligence (DMI) and issued to MI5 and MI6, as it appears in Per Ardua Libertas, a photographic summary of MI9’s work, produced by Christopher Clayton Hutton in 1942.

The responsibilities included a mixture of operations, intelligence, transport and supply. The newly formed section was initially located in Room 424 of the Metropole Building (formerly the Metropole Hotel) in Northumberland Avenue, London, close to the War Office’s Main Building.

NORMAN CROCKATT

The newly appointed Head of MI9 was Major, later promoted to Colonel and eventually to Brigadier, Norman Richard Crockatt (1894–1956), a retired infantry officer who had seen active service in World War I in the Royal Scots Guards. Crockatt had left the Army in 1927, worked in the City and was in his mid-forties at the outbreak of World War II.

Whilst he had been decorated in World War I (DSO, MC), he had never been captured and, therefore, had no experience of being a prisoner of war. He proved, however, to be an admirable choice to ensure the fledgling section made good progress in its infancy and throughout the war, being ‘clear-headed, quick witted, a good organizer, a good judge of men, and no respecter of red tape’ (as recorded by M. R. D. Foot and J. M Langley in their definitive history MI9: Escape and Evasion, 1939–1945, hereafter referred to as Foot and Langley). These qualities were to stand him in good stead for the work he tackled in the next six years. He also recognized the importance of keeping his section small, concentrated in its activities and low profile among other intelligence sections, attributes which appeared to ensure that when the time came to expand its activities, it received little opposition from those competing for military priorities and budgets. Crockatt realized the value of having the experience of former prisoners of war, especially those who had successfully escaped, and appointed many with that experience to the small cadre of lecturing staff based in the Training School established by MI9.

Brigadier Norman Crockatt in the MI9 headquarters at Wilton Park near Beaconsfield in 1944.

The initial budget given to Crockatt to set up the entire section was £2,000. In present day terms, this equates to a sum of approximately £90,000. He embarked on a recruitment campaign and, by the end of July 1940, the complement of officers in the whole of the MI9 organization had risen to fifty. By that time, Crockatt was looking to move his organization out of London and by September 1940, he had selected Wilton Park, near Beaconsfield, as an appropriate location. After necessary refurbishment and the installation of telephones, most of the MI9 staff moved there on 14–18 October and occupied No. 20 Camp at Wilton Park.

ORGANIZATION

The section was initially organized into two parts: MI9a was responsible for matters relating to enemy prisoners of war and MI9b was responsible for British prisoners of war. The former subsequently became a separate department, MI19, to facilitate the handling and distribution of the intelligence information emanating from the two groups. On separation, the remaining MI9b was re-organized into separate sections and the staff complement was significantly increased:

Section D was responsible for training, including the Training School which was established at the Highgate School in north London, from which the staff and pupils had been evacuated. It was subsequently designated the Intelligence School (IS9) in January 1942.

Section W was responsible for the interrogation of returning escapers and evaders, including the initial preparation of the questionnaires which the interviewees were required to complete. The principal aim of the questionnaires was to identify information for use in the lectures and the Bulletin. The section was also responsible for the preparation and distribution of reports and for writing the daily, later to become monthly, War Diary entry.

Section X was responsible for the planning and organization of escapes, including the selection, research, coordination and despatch of escape and evasion materials. Because of the small numbers of staff, the section was unable to spend much time on this activity until January 1942 when its establishment was boosted. At that point, they were also able to increase the volume of information to Section Y for transmission to the camps.

Section Y was responsible for codes and secret communication with the camps. The development of letter codes as a means of communication with the camps was regarded as a priority from the start and the role which coded communication played in the escape programme is discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

Section Z was responsible for the production and supply of escape tools, including all related experimental work.

It is primarily these last three sections whose activities largely, but not exclusively, form the focus of this book.

KEY STAFF

Christopher Clayton Hutton

Christopher William Clayton Hutton (1893–1965), known as ‘Clutty’ by all who worked with him, was appointed on 22 February 1940 as the Technical Officer to lead Section Z. He was the boffin, the inventor of gadgetry. His fascination for show business, particularly magicians, was apparently regarded as sufficient qualification for the post he was given as the escape aids expert in MI9. It was his innate interest in escapology and illusion which was to prove the source of his imagination and ingenuity. Whilst working in his uncle’s timber business in Park Saw Mills, Birmingham prior to World War I, he had challenged Harry Houdini to escape from a packing case constructed on the stage of the Birmingham Empire Theatre. Houdini escaped, for, unbeknown to Hutton, he had bribed the carpenter. In the inter-war years, he worked as a journalist and later in publicity for the film industry.

Christopher Clayton Hutton, who led MI9’s Section Z from 1940 to 1943, where he developed many ingenious escape aids and initiated the escape and evasion mapping programme.