По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

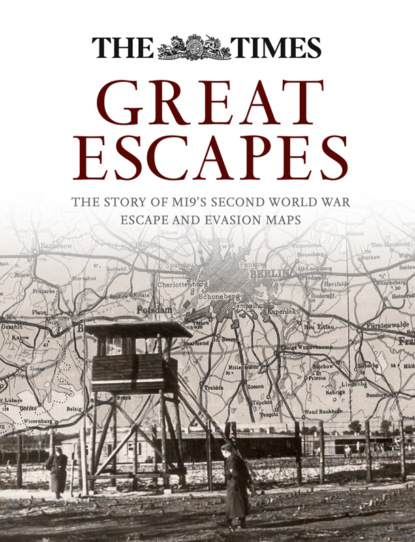

Great Escapes: The story of MI9’s Second World War escape and evasion maps

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

MI9’s War Diary entry for 31 March 1940 reflects just how quickly Hutton got to grips with the task he faced: the entry indicates that even by then, just three months into MI9’s operations, available escape devices already included ‘maps on fabrics and silk, maps concealed in games, pencils, articles of clothing’. Hutton had tried to find a paper which was thin, resistant to the elements and soundless when hidden inside Service uniforms, which was what he was planning to do. After talking to contacts in the trade, he became convinced that such a paper did not exist and so turned his attention to fabric, and to silk in particular.

John (known as Ian) Bartholomew, of the Edinburgh cartographic company John Bartholomew & Son Ltd, in the trenches near Ypres in 1915.

A printed Bartholomew map of France at 1:2M, used by MI9 as its ‘Zones of France’ map, but with southern England removed.

Detail from the same map.

THE HISTORY OF MILITARY MAPS ON SILK

Hutton was almost certainly unaware that the efficacy of silk as a suitable medium for military maps had long been recognized. Indeed, the oldest surviving silk map in the world is a military map, known more commonly as the Garrison Map, excavated in 1973 from the Han Dynasty Tomb No. 3 in Mawangdui, Changsha, in Hunan Province, China. It was one of three silk maps found on the site, the others being a topographical map of the region and a city map. The Garrison Map has been dated to the middle of the second century BC. It was unearthed in twenty-eight fragments, moisture and pressure having taken their toll during 2,000 years of burial in a small box. The fragments were restored and then a reconstruction of the map was undertaken by Chinese scholars.

The Garrison Map covers the region between Mount Jiuyi and the Southern Ridges in Ningyuan in southern Hunan province, China. The map shows mountains, rivers and residential settlements, and in particular it indicates the locations of the garrisons, defence regions, military facilities and routes of nine army units. It is the oldest known map on silk, dating from the second century BC

A reconstruction of the Garrison Map.

The map carries no indication of scale but, by comparing it with modern mapping, it is estimated to be in the range 1:80,000 to 1:100,000. It has been drawn on a rectangular piece of silk which measured 98 cm by 78 cm. The map was originally drawn in three colours, black, red and blue/green, using vegetable-based tints and is orientated and marked with south at the top and the left side marked east. Water features are shown in blue/green, with some background features and place names in black but the military content of the map is emphasized in red, showing the size and disposition of army units, command posts, city walls and watchtowers. Settlements are shown, together with the numbers of inhabitants. The boundary of the garrisoned area is marked and frontier beacons (observation outposts) are shown. Topographic detail is stylized, so that mountains are shown as wavy lines rather than by any attempt to represent their real form and shape. Roads are shown with distances between some settlements clearly marked, as are river crossing points: in modern military parlance, this is referred to as ‘goings’ or terrain analysis information and was a technique also utilized by MI9 in the production of some of their special area escape and evasion maps.

While the Chinese are understandably keen to stress the relevance of the three maps in terms of how they reflect their nation’s achievements in surveying and mapping techniques in the wider context of historical cartography during the period of the Han Dynasty, the relevance here is that the Garrison Map was undoubtedly produced for military purposes and was drawn on silk. There are later examples of military mapping produced on silk in China. Seventeen hundred years after the Garrison Map was produced, the Garrison Outline Map of Shanxi was produced during the Ming Dynasty, although the later map was regarded by Chinese scholars as greatly inferior to the Han Dynasty Garrison Map, not least because the earlier map was drawn in colour and showed far more military detail than the Shanxi map.

In the USA during the Civil War, General Sherman was known to have had monochrome maps printed on cloth during the Atlanta campaign. The Library of Congress map collection contains many examples of Civil War maps printed on cloth, including the map illustrated here, showing ‘Part of Northern Georgia’, produced by the Topographical Engineer Office in Washington DC in 1864.

The Intelligence Division of the US War Department in Washington DC produced a map of Cuba in 1898 and one of China in 1900, both printed on cloth. Details of these examples were contained in a letter dated 18 October 1927, written by Lieutenant Colonel J. C. Pegram, Chief of the Geographic Section of the Military Intelligence Division to Colonel R. H. Thomas, Director of Map Publications in the Survey of India in Calcutta, apparently in response to an enquiry from the latter. Interestingly Pegram highlighted the extent to which a medium more durable than paper was a necessity when the constant use, repeated folding and effect of the elements quickly rendered paper maps unusable in the field. He indicated that their engineers were currently addressing the problem of printing maps on cloth, were improving their techniques and getting good results, although he offered no technical details to support this statement. The challenge of printing on fabric was essentially that the cloth had to be held taut during the printing process so that the image would not be distorted.

This map, printed on cloth, covers part of northwestern Georgia and adjacent Alabama to the west of Atlanta. It is annotated in blue pencil in the upper margin: ‘Specimen of field maps used in Sherman’s campaigns, 1864’.

Detail from this map.

Detail from Ordnance Survey one inch map of the Lake District (Keswick), printed on silk and dating from 1891.

The flexibility and durability of fabric, both silk and linen, as a medium for military maps had clearly long been recognized, a fact that had been reflected in the UK Government’s report of the War Office Committee tasked in the closing decade of the nineteenth century to consider the precise form of the military map of the UK. The Committee made frequent mention in its Report, published in 1892, and throughout the minutes of evidence, to the superior durability of linen over paper as a material on which maps could be printed for use in the field. Almost certainly related to the Committee’s work, although not acknowledged as such, the Ordnance Survey was simultaneously printing some of its one inch series of the Lake District on silk. Copies of two sheets, Ambleside and Keswick, are known to exist in a private collection and they are dated 1891. Ordnance Survey was still, at that time, staffed at senior levels by sapper officers from the Corps of Royal Engineers, so it is more than likely that they would have been called on by the War Office to do prototype printing experiments for military purposes. It is, however, notable that no mention of this work appears in the definitive history of the Ordnance Survey which concentrates rather on the work of the Dorington Committee which was taking place at the same time, charged with looking at the state of Ordnance Survey mapping after considerable public disquiet had been expressed.

With hindsight, it becomes very clear that the knowledge and capability to print maps on silk existed in the UK at the time of World War II and that the military had for centuries recognized the value of fabric maps, whether silk or linen, in terms of their durability and flexibility. Hutton’s search and ultimate decision to produce maps on silk might have been made more promptly and with far less effort and cost had he spoken to the military map-makers. Certainly both the Directorate of Military Survey (D.Survey), the principal military mapping organization, and the Ordnance Survey doubtless had the expertise but, for unknown reasons, they were apparently never consulted by Hutton, who preferred rather to approach commercial printers, paper manufacturers and silk processors. This is rather surprising, bearing in mind the covert nature of MI9’s activities and the secrecy which surrounded every aspect of their work, not least the mapping programme. It does, however, largely explain why MI9 paid little attention in their map production programme to the finer points of cartography and the standard techniques of identifying the maps they produced, as will be outlined in the next chapter.

3 (#ulink_694154b0-b39f-5a56-833e-91f48e1a09c5)

THE MAP PRODUCTION PROGRAMME (#ulink_694154b0-b39f-5a56-833e-91f48e1a09c5)

‘Geography is about maps . . .’

(Edmund Clerihew Bentley, from Biography for Beginners, 1905)

The detail of MI9’s mapping programme, which became such an important part of their escape programme, has been difficult to piece together. No single, comprehensive record of the production programme has ever been found and only now, in 2015, is a record set of the maps being deposited in The National Archives by the Ministry of Defence. Copies of the maps have been found in many collections, both public and private, throughout the country. There is, however, very little mention of the maps in the published literature and some of the possibly relevant MI9 files in The National Archives are still closed.

Reconstructing the story has proved to be like the reassembly of a jigsaw puzzle where some pieces are still missing, possibly lost for all time. The records that remain make it difficult to describe and record the extent of the programme and the challenges faced in ensuring the quality and utility of the maps for their intended users. It is likely that MI9 kept a card index of the individual maps in the programme in the same way as they are known to have kept a card index to maintain a record of other aspects of their work. Sadly, none of the card indexes appear to have survived and there is, therefore, no comprehensive record of MI9’s escape and evasion map production programme available.

The programme has had to be pieced together from, sometimes, fragmentary information. The single most comprehensive record is undoubtedly the D.Survey war-time print record which was created, managed and kept up-to-date by Survey 2, that part of D.Survey responsible for the management of all operational map production programmes. This card index was originally found as an uncatalogued item in the India Office Library and Records, housed in the British Library. How it came to be held there, rather than in The National Archives where one might reasonably anticipate finding it, is an enigma, but it has now been catalogued by the British Library.

The second source is a typed list held in one of the War Office files. There is also a third source, a list deposited in the British Library by the archivist of John Waddington Ltd, the Leeds company that printed many of the maps, referred to as ‘pictures’ in their list and in their dealings with the Ministry of Supply. Intriguingly, the typed War Office list also refers to the maps as ‘pictures’, and it is, therefore, likely that it had its origins in the Waddington list.

A selection of escape and evasion maps produced by MI9.

The contents of the three sources are similar but by no means identical. Some of the differences can be explained by apparent human error (misreading of sheet numbers and typographic errors, for example). However, the War Office typed list contains other differences which are less understandable: for example, it states that twenty-nine sheets were produced in a series of maps of Norway, identified by the designation GSGS 4090, whereas the print card index indicates that the series consisted of thirty-three sheets, which proved to be correct since surviving copies of all thirty-three sheets have been identified.

While the print records were originally classified SECRET, some of the detail of the programme was apparently regarded as so sensitive that it was not declared openly even on that classified record. For example, it took some time to confirm, through seeing surviving copies, that the description of one map as ‘D - - - - G’ was a large-scale plan of the port of Danzig and that ‘Dutch Girl’, in four sheets, referred to Arnhem. Other entries on the record remain a mystery: for example, ‘Double Eagle’, although it might reasonably be conjectured that it was a map of Germany and Austria. Indeed, one of the earliest maps produced by MI9 was a small-scale map of Germany, Austria and adjacent frontier areas: it carried the sheet number A, probably indicating that it was the first sheet to be produced. No direct evidence has yet been unearthed, however, to confirm that this is the map which the record describes as ‘Double Eagle’.

Sheet A showing Germany and Austria at 1:2,000,000 scale, one of MI9’s earliest silk maps, which used Bartholomew mapping. It may be the map referred to as ‘Double Eagle’ in the War Office print records.

Where copies of individual sheets (either singly or in combination) survive, it has proved possible to identify the particular print medium, i.e. tissue (a very fine paper), silk or man-made fibre (MMF), almost always rayon but sometimes referred to as Bemberg silk. In some cases it has proved possible to be more precise. The Waddington list, for example, indicates that some of the maps were printed on Mulberry Leaf (ML) paper or Mulberry Leaf Substitute (MLS). Appendices 1–9 record the details of all the maps so far identified using these sources, including coverage, scale, dimensions, production details such as colour, print quantities and combinations, print medium, print dates and location of surviving copies.

MI9’S CARTOGRAPHIC INEXPERIENCE

MI9 may have been the initiators of the escape and evasion mapping programme but they were apparently not well versed in cartographic techniques, processes and procedures. Very many of the maps lack even basic identification. Many carry no title, series designation, date or edition number, and some carry no scale indicator. The proper referencing of military mapping is of fundamental importance in an operational scenario to ensure that everyone is using the same, and most up-to-date, version of the map. Even when cartographic referencing information is shown by MI9, it can prove to be very misleading. The most obvious examples of this are the sheets of GSGS Series 3982. The original operational map series designated with this GSGS (Geographical Section General Staff) number was the Europe Air series at a scale of 1:250,000 which existed prior to the outbreak of the War. These were reproduced as escape and evasion maps, largely on silk and tissue, at a reduced scale of 1:500,000. In reducing the scale, MI9 did not in any way alter the detail shown on the original map (even the series number) with the exception of the scale factor, so that on the resultant sheet, the font size of place and feature names is very small, although the detail is still legible.

Sheet D of [Series 43] showing the title which identifies it as using ‘New Frontier’ and with the legend which identifies ‘Former Frontiers’ and ‘Present Frontiers’.

The date on most of the sheets was in fact often the date of the original operational paper map and not the date of the escape and evasion map production. This is notably the case where compilation and imprint dates shown on the escape and evasion maps pre-date the start of the escape and evasion map production programme itself. This is also confirmed by the imprint numbers shown in the marginalia, often indicating print volumes well in excess of those produced as escape and evasion versions. The one exception to this was where boundaries are shown ‘at 1943’, for example in [Series 43]. Indeed, when D. Survey eventually assumed responsibility for escape and evasion map production in 1944, they proposed changes to the printing colours of boundaries and country names. In a letter dated 28 November 1944, MI9 came back strongly opposed to change, insisting that their policy of ‘present frontiers in red and pre-Munich frontiers in mauve’ be adhered to, not least because it had always been specified as such in their training courses and lectures.

Detail from Bartholomew sheet C showing that MI9 stripped out most of the coverage of SE England in case copies fell into enemy hands.

Sheet A4 showing details of the port of Danzig.

MI9’s lack of knowledge of map production processes and procedures manifested itself in many other ways. It is a cardinal cartographic rule that different versions of the same map are identified differently, usually by a change in the edition number or, at the very least, in the production/print date. Both MI9 and the companies they initially used to print the maps were oblivious to such practices. As a result, the escape and evasion maps carried no edition numbers or production dates, and some maps apparently identified as being the same were in fact different. To give a few examples: there were at least two versions of sheet C with one version extending one degree longitudinally further east than the other version.

There were also at least three versions of the Danzig port plan. Whilst all three versions provided large-scale coverage of the port of Danzig, one carried the sheet number A4, whereas the second version carried no sheet number and the third carried the sheet number A3. The three versions varied also marginally in scale and in geographical extent. They also carried different intelligence annotations, the sheet marked A4 carrying far more intelligence information than the other two versions, in the form of annotations directing escapers, for example, where to find Swedish ships, where the arc lights were located and how far the beam of light extended. In the case of sheets J3 and J4 (covering Italy), the geographical areas of coverage of the two sheets were sometimes reversed and the scale was varied, sometimes being produced at 1:1,378,000 and at other times reduced to 1:1,500,000 (see Appendix 1).

Detail showing the sheet identifier from sheet S3 of the Bartholomew series; sheet S2 is printed on the reverse so the identifier S3/S2 has also been included.

These are the principal variations identified to date: there may well be others yet to be discovered. It is important to describe them in detail since they are only really identifiable when surviving copies of the maps can be compared. The differences do, however, highlight the extent to which individual sheet identification of MI9’s escape and evasion maps needs always to be treated with caution.

The solution to the challenges posed by MI9’s lack of adherence to usual cartographic identification procedures has been to use the standard cartographic technique of showing in square brackets [ ] any information which does not appear on the printed maps but which helps to identify them. The series number and series title, for example [Series 43] and Series GSGS 3982 [Fabric], have been rendered in this form to aid identification.

Where the base map used for escape and evasion map production carried no sheet number, MI9 devised an arbitrary sheet numbering system. In the case of their early attempts based on the maps of John Bartholomew & Son Ltd of Edinburgh, the sheets carried an upper case Roman alphabet letter, often in conjunction with an Arabic number, for example C, H2, or S3.

MI9 caused themselves significant production problems when they decided (for unknown reasons) to cut and panel sheets to produce an escape and evasion map by piecing together up to nine sheet sections of an existing operational series, rather than simply reproducing the operational map sheets on their existing sheet lines. [Series 43] is a good example of this practice. It is clear that this escape and evasion series was produced by panelling together sheets or sections of sheets from the International Map of the World (IMW) series. There are examples of coverage diagrams in the surviving files of the composition of sheets created by this method. There are also indications that the practice caused considerable angst to the regular military mapmakers when they eventually became involved in the escape and evasion production programme. On 3 December 1944, Lieutenant Colonel W. D. C. Wiggins of D.Survey wrote to MI9:

Your proposed sheet lines do not (I have noticed this on previous layouts of yours) take into consideration existing map series sheet lines, printing sizes or fabric sizes. . . . Production is much simpler if we stick to graticule sheet lines as opposed to your, rather vague, rectangulars.

He might also have added that the practice must have greatly increased the production costs. The point appears to have been disregarded by MI9 who continued with arbitrary sheet lines and numbering systems, exemplified by [Series 43], [Series 44] and [Series FGS].

MAPS BASED ON BARTHOLOMEW MAPPING (AND OTHER MAPS WITH SIMILAR SHEET NUMBERS)

As Christopher Clayton Hutton indicated in his book, Official Secret, MI9 initially worked in isolation from the military map-makers and chose rather to approach commercial map publishing firms directly for help. As previously described, Hutton had contacted the firm of John Bartholomew & Son Ltd in Edinburgh at the suggestion of Geographia in London. It was Ian Bartholomew, the Managing Director, who gave Hutton his first lesson in map-making. Hutton himself indicated that ‘thanks to the assiduities of the managing director and his staff . . . I learned all there was to know about maps’. Hutton was given copies of many of Bartholomew’s own maps of Europe, Africa and the Middle East, which then formed the basis of MI9’s initial escape and evasion map production programme. The waiving of all copyright charges for the duration of the war was a considerable financial gesture from Bartholomew since MI9 went on to produce in excess of 300,000 copies of the maps (details of the print runs are given in Appendix 1).

The maps are readily identifiable as using Bartholomew mapping since they are identical, in specification, colour and font style, to the company’s maps of the time. They are generally small-scale (1:1,000,000 or smaller), produced in three colours (red, black and grey/green) and without elevation detail. A few of the maps carry confirmation of their source since they clearly show the Bartholomew job order number relating to the original paper map along the neat edge of the silk map. The alpha-numeric code A40 which appears in the northwest corner of some copies of sheet F was very much a Bartholomew practice. The company introduced this code in the early part of the twentieth century, mostly on their half inch-scale mapping. The formula is a letter (either A, for January–June or B, for July–December) followed by a two-digit number representing the year of printing, so A40 indicates that the original paper version of this map was printed between January and June 1940.

Sheet K3, printed on rayon, was based on Bartholomew mapping, primarily showing northwest Africa.

Summary of Bartholomew series used by MI9