По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

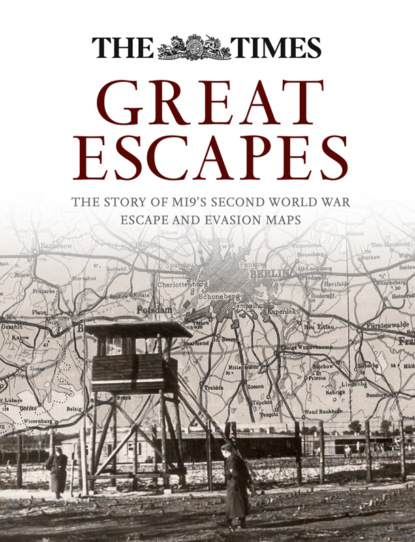

Great Escapes: The story of MI9’s Second World War escape and evasion maps

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hutton had served in the Yeomanry, the Yorkshire Regiment and as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps during World War I. Realizing that another war with Germany was imminent, he tried to volunteer for the Royal Air Force and, subsequently, for the Army. When these approaches did not receive the encouragement he sought, he wrote a number of times to the War Office seeking an opening in an Intelligence Branch, an approach which eventually resulted in his appointment to the newly formed MI9 under Crockatt’s leadership.

‘Clutty’ was regarded as both enthusiastic and original in his approach to the task to which he was appointed. He is variously described by his contemporaries as ‘eccentric’, ‘a genius’ and by Foot and Langley as ‘wayward and original’. He wrote an account of his time in MI9, which ended during 1943 as a result of illness, under the title Official Secret (1960), but the publication of the book was not straightforward (see Chapter 9)

Crockatt very quickly recognized the value of having those who had experienced the reality of escape and was also conscious of the need to have representatives of all three Services in his organization. To this end, he appointed two Liaison Officers from the Royal Navy and the RAF.

Johnny Evans

From the RAF he appointed Squadron Leader A. J. Evans, MC (1889–1960). Johnny Evans, as he was always called, was an inspired choice. Appointed in January 1940, Evans very rapidly became a most valuable member of the MI9 team, becoming one of the star performers as a lecturer at the Training School. He had been an Intelligence Officer on the Western Front in World War I and had then been commissioned as a Major into the fledgling Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Shot down behind German lines over the Somme in 1916 and captured, he was eventually sent to the prisoner of war camp at Clausthal in the Harz Mountains.

For Evans, remaining in captivity was apparently never an option. Whether this in any way reflected his upbringing and public school education at Winchester is unclear but it certainly did not reflect military training at the time. He escaped, only to be recaptured. On recapture he was sent to the infamous Fort 9 at Ingolstadt, north of Nuremburg, the World War I equivalent of Colditz in World War II. It was the camp to which all prisoners of war who had attempted to escape were sent and was located over 160 kilometres (100 miles) from the Swiss frontier. Evans described in considerable detail both his failed escape and his eventual successful escape in his best-selling book, The Escaping Club, published in August 1921, and reprinted five times by the end of that year. It took him and his companion almost three weeks to walk, largely at night, to the Swiss frontier which they crossed at Schaffhausen, west of Lake Constance.

Johnny Evans, from his classic book, The Escaping Club, published in 1921.

Evans described the attitude of the men in Fort 9 and the extent to which they spent their time in the all-consuming occupation of plotting to escape. It really was a veritable ‘Escaping Club’ where failed escapers were only too ready to share the knowledge of their experiences outside the camp with their fellow inmates. Evans described the receipt of clothes and food parcels from family and friends in which maps and compasses were also hidden. This was apparently accomplished by the prior personal arrangement of using a simple code in correspondence detailing the specific needs, maps, compasses, saws, civilian clothing and the like. Maps arrived in the camp secreted inside cakes baked by his mother or in bags of flour, and compasses inside bottles of prunes and jars of anchovy paste. The maps were copied in the camp so others could also use them and were then sewn into the lining of jackets.

Sketch map of Fort 9 Ingolstadt showing the escape routes of Johnny Evans

It is fascinating to consider the extent to which Evans brought these experiences to bear in his work for MI9 and understandable that his book was dedicated:

To MY MOTHER who, by encouragement and direct assistance, was largely responsible for my escape from Germany, I dedicate this book which was written at her request.

He went further, however, spending time prior to the outbreak of World War II visiting the Schaffhausen area of the German–Swiss border, across which he had made his own successful bid for liberty in World War I, photographing the border area and making copious notes. It cannot be coincidence that the MI9 Bulletin contained two large-scale maps of the Schaffhausen Salient, together with ground photographs of the local topography, showing distinctive landmark features, for example the stream and footpath where the German border guards patrolled. MI9’s map production programme also included sheet Y, a large-scale map of the Schaffhausen Salient which carried very detailed notes of the topography and landscape features to help escaping prisoners of war (see Chapter 6 for the significance of this map in the MI9 programme and Appendix 1).

Jimmy Langley, who organized covert escape routes for MI9, and later co-authored the definitive history of MI9.

Jimmy Langley

Lieutenant Colonel James Maydon Langley (1916–83), called ‘Jimmy’ by friends and colleagues, was born in Wolverhampton, educated at Uppingham and Trinity Hall, Cambridge. As a young subaltern in the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards, he was badly injured in the head and arm and left behind at Dunkirk: on a stretcher as he would have taken up space which four fitter men could have occupied. He was taken prisoner, hospitalized in Lille and had his injured left arm amputated by medical staff. He subsequently escaped, in October 1940, by climbing through a hospital window and managed, with a still suppurating wound and with help from French families who befriended him, to reach Marseilles from where he was repatriated, with help, through Spain to London. Langley successfully navigated by using the maps of the various French departments which appeared in every public telephone kiosk in France. The couple of times he travelled in the wrong direction resulted from the maps being oriented in a non-standard fashion, with East at the top. So Langley, too, knew the value of maps as an escape tool.

He arrived back in the UK in the spring of 1941 and initially joined SIS. He soon transferred to MI9 but remained on the payroll, and therefore technically under the command, of SIS. In practice he became the liaison point between the two organizations and was responsible for the work of the escape lines in northwest Europe. These were the covert routes along which the escapers and evaders travelled on their journey home, being helped by members of the local communities along the way. The network was established by MI9 working from London and also through legation staff and embassy attachés. If discovered by the Germans, as many of the French, Belgian and Dutch nationals were, they were executed or sent to the concentration camps. He remained in post for the duration of the war, and subsequently married Peggy van Lier, a young Belgian woman who had been a guide on the Comet Line (the organized escape route through western France and across the Pyrenees into Spain – see page 148). Over thirty years later, he co-authored with M. R. D. Foot MI9: Escape and Evasion, 1939–1945, which came to be regarded as the definitive history of MI9. He also wrote his own account of his early life, capture, hospitalization and subsequent escape in Fight Another Day, published in 1974.

Airey Neave

Of others in Crockatt’s team, perhaps Airey Middleton Sheffield Neave (1916–79) is the most famous. As a young lieutenant, he was a troop commander in the 1st Searchlight Regiment of the Royal Artillery. He was wounded and captured in Calais Hospital in May 1940 as the Germans over-ran northern France. He was held in various oflags and, after a number of unsuccessful escape attempts, he was eventually imprisoned in Oflag IVC, the castle in Saxony more commonly known as Colditz. Working with his Dutch colleague, Toni Luteyn, Neave escaped from Colditz on 5 January 1942, the first British Officer to escape successfully from that infamous camp. After reaching Switzerland, Neave was repatriated through Marseilles and into Spain via the organized escape route known as the Pat Line (see page 148). After a short period of leave, he joined MI9 in May 1942 under the pseudonym (code-name) of Saturday. It is clear that his name had been on an MI9 list of targeted officers who had been specifically helped to escape, and his experience was to prove invaluable. His escape and the extent to which it reflected the value of MI9’s mapping programme are issues considered in detail in Chapter 6. His account, They Have Their Exits (1953), covered his experiences on the frontline, his capture and initial, unsuccessful attempts at escape followed by his escape from Colditz. Neave also wrote about MI9 in Saturday at MI9 (1969), which is discussed in the Bibliography.

Airey Neave was the first British officer to escape from Colditz.

THE TRAINING SCHOOL AT HIGHGATE

Section D of MI9 was responsible for training and briefing the Intelligence Officers who attended courses at the Training School in Highgate and who then returned to their individual units to provide training to operational crews. Certainly in the early years, these training courses concentrated on the RAF whose crews were constantly overflying occupied Europe. The lecturers engaged were largely those who had personal experience of escape in World War I. Their remuneration was set at two guineas (£2. 2s. 0d.), the equivalent of around £82 today, for each lecture they delivered and they were also provided with travel and overnight hotel expenses when they travelled to deliver lectures at operational units. As early as January 1940, a conference was organized in Room 660 of the Metropole Building to hear a lecture delivered by Johnny Evans. By the end of February 1940, lecturers from the Training School had delivered their training lectures to seven Army Divisions, and five RAF Groups, and were undertaking a tour of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

The content of the general lecture given to officers and senior noncommissioned officers (NCOs) included emphasis on the undesirability of capture, instructions on evasion, conduct on capture and a demonstration of some of the aids to escape which were issued to units prior to deployment. The lecture emphasized that the job was to fight and avoid capture. If captured, it was their first and principal duty to escape at the earliest opportunity. Later on in the war, with the increasing numbers of prisoners of war and the increasing organization of Escape Committees in the camps, the lectures were updated to include mention of the Escape Committees, which were the responsibility of the Senior British Officer in each of the camps.

Those attending the training courses were told that money, maps, identity papers, provisions and many other escape aids would be made available through the Committees. The officers and NCOs who attended the lectures were then responsible for cascading the briefing down through the ranks, but they were, initially at least, specifically directed not to mention the aids to escape as they were only available for issue in limited numbers. It was recommended that they deliver the lecture as an informal talk, classified SECRET, and to audiences which should not exceed 200 at any one time. Later on, and certainly by early 1942, a supply of aids for demonstration purposes was provided to local commands.

There was also a classified TOP SECRET lecture on codes which was delivered under the title of ‘Camp Conditions’ to very limited audiences, never more than ten at a time, all of whom had been carefully selected. Those selected for this special briefing were required to practise the use of letter codes and their work was carefully checked before they were formally registered as authorized code users. Section Y was responsible for codes. The development of letter codes as a means of communication with the camps was also regarded as a priority from the start and the role which coded communication played in the escape programme developed apace. This aspect is discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

The staff in the Training School steadily compiled a training manual which became known as the Bulletin. The Bulletin served an important role as a tool in educating potential prisoners of war about possible escape routes and the nature of escape aids, including maps, which were being produced (see Chapter 4).

The pressures on the lecturing staff were considerable and continually increased as the war progressed. Initially both the Royal Navy and the Army had appeared uninterested in the training courses offered and, certainly in the first year or so of its existence, MI9 staff worked hard to stimulate interest and used many personal contacts to raise awareness of their work. They appeared to overcome some initial opposition from the Royal Navy and some Army commands, and by May 1944 the record shows that very significant numbers in all three services had been briefed: 110,000 in the Royal Navy and the Royal Marines, 346,000 in the Army and 290,000 in the Royal Air Force, and a total of 3,250 lectures had been delivered.

ESCAPE-MINDEDNESS

Escape-mindedness was the term which Crockatt coined to describe the philosophy which he sought to instil into the frontline forces which his staff regularly briefed and trained. Inculcating and fostering this philosophy was the primary aim of the training, and the rest of the MI9 team was working to ensure that the approach was supported in a very practical way. They stressed that, if captured, it was an officer’s duty to attempt to escape and, not only officers, it was a duty which extended to all ranks. Many years after the end of the war when Commander John Pryor RN came to write his memoirs of the years he spent as a prisoner of war during World War II, it is not surprising that he recalled that:

escaping was the duty of a PoW but with the whole of NW Europe under German control and with no maps or compass it seemed a pretty hopeless task.

Stalag Luft III (Sagan), drawn by the artist Ley Kenyon, who was a prisoner in the camp. It shows the position of Tom, Dick, Harry and George tunnels. Harry was used in the ‘Great Escape’.

The briefings and training which MI9 provided alerted officers to every aspect of potential evasion and escape. The emphasis was on evading capture whenever possible or, if captured, to attempt to escape at the earliest opportunity and certainly before being imprisoned behind barbed wire in the many prisoner of war camps. It was standard practice for captured officers to be separated into oflags from the other ranks who were kept in stalags. Officers were, therefore, made responsible for ensuring that their men were appropriately briefed about what to do in captivity and the organization of Escape Committees became one of their principal priorities.

It is perhaps a reflection of the extent to which the philosophy permeated the camps that by the time the Allies were landing in occupied Europe and slowly advancing east, it was felt necessary to issue a ‘stay-put’ order to prisoners of war to ensure they did not get caught up in the frontline whilst trying to flee captivity. The order was sent by MI9 on 18 February 1944 in a coded message: it directed that

ON GERMAN SURRENDER OR COLLAPSE, ALL P/W ALL SERVICES INCLUDING DOMINION & COLONIAL & INDIAN MUST STAY PUT & AWAIT ORDERS

Many families also wrote to their sons in the camps strongly discouraging them from any escape attempts, as a result of the Stalag Luft III (Sagan) experience when fifty of the men who had taken part in the ‘Great Escape’ in March 1944 were executed on being recaptured.

The MI9 staff who subsequently wrote about their escapes, notably Neave and Langley, and even Evans who had escaped during World War I, all highlighted the importance of an escape philosophy. Neave described the way in which escapers had ‘to think of imprisonment as a new phase of living, not as the end of life’ and the extent to which the real purpose of the escaper was ‘to overcome by every means the towering obstacles in his way’. It was a state of mind that MI9 encouraged.

It was understandable that some might prefer the relative safety of the camp rather than life on the run. Even for these men there were jobs to be done to support the escapes of others. It was strength of mind and purpose which was needed rather than just physical health and strength, a point epitomized by the escapes of Jimmy Langley, still suffering from a suppurating amputation wound, and Douglas Bader, restricted by his two artificial legs. Initiative, foresight and courage were needed and luck also came into it: as Evans stressed, ‘however hard you try, however skilful you are, luck is an essential element in a successful escape’, while David James noted in A Prisoner’s Progress (1947) that:

Luck is the most essential part in an escape . . . for every man out, there were at least ten better men who would have got clear but who did not have the good fortune they deserved.

Teamwork is the one competence which comes through all the stories and plans relating to escape. This almost certainly reflected the public school philosophy where your efforts were for school, house and team rather than for self. As an Old Wykehamist, Evans personified this approach and it is not surprising to learn that between the wars he captained the Kent county cricket team. To some extent it could be argued that MI9 was pushing at an open door in seeking to inculcate Crockatt’s philosophy into a new generation of young men. Many of them had been educated at preparatory and public schools and apparently raised on a diet of escape classics of the last war. Some of them acknowledged this when they came to write their own accounts of their escape experience during World War II, as James recorded:

In my prep-school days at Summer Fields, I had read all the escape classics of the last war – such books as The Tunnellers of Holzminden, Within Four Walls, I Escape, and The Escapers’ Club [sic] – and as a proposition the business of escaping fascinated me.

It is clear from their post-war accounts that many escapers spent every waking moment of captivity plotting their escape. Some identified the very human traits which they believed could most aid them. Gullibility (of the captor) and audacity (of the escaper) were high on the list, as was luck. There was a psychology attached to escaping, as James recognized:

I came to the conclusion that escaping was essentially a psychological problem, depending on the inobservance of mankind, coupled with a ready acceptance of the everyday at its face value.

The Germans were apparently well aware of this philosophy and the extent to which it sustained British prisoners of war and constrained their own resources in guarding those captured and seeking to prevent their escape. Once the Allies had landed in mainland Europe and started to advance east, they captured not simply German troops but also a number of key German documents amongst which was a document identified as GR-107.94. It must have made fascinating reading for MI9 as it revealed the extent to which the Germans were well aware of their work. It is a lengthy document and relates entirely to the escape methods employed by Allied Flying Personnel. It was dated 29 December 1944 and described the escape philosophy, the duty to escape, and the maps provided on silk and thin tissue. It goes so far as to list nine maps which they knew had been produced. Whilst it reflected the extent to which the Germans were aware of what they were up against, it also indicated that, if they were aware of only nine escape maps when MI9 had by that time produced over 200 individual items and over one and three quarter million copies, they had arguably only discovered the proverbial tip of the iceberg.

2 (#ulink_51841a54-dd86-57c9-8727-130d20530a5c)

BACKGROUND TO THE MAPPING PROGRAMME (#ulink_51841a54-dd86-57c9-8727-130d20530a5c)

‘For some time our engineers have been working on the problem of printing maps on cloth . . . the necessity of a durable material for maps was impressed on me a number of years ago . . . I was sent with my troop on an independent mission . . . about the second day, due to folding, use and the action of the elements, my map was almost illegible and I was travelling by a cavalryman’s knowledge of the terrain.’

(Lieutenant Colonel J. C. Pegram, Chief of the Geographic Section of the US War Department, in a letter dated 18 October 1927)

The story of the mapping programme has to be set in the climate of the times. The young men of the inter-war period, and especially the officers, most of whom had been educated in the British public school system, had been raised on a culture of escape stories from the Great War. They had read many of the books which had been written by the great escapers from World War I, people like Durnford, Evans and others. They had also been made more aware of the relevance of geography in their curriculum, of map reading and navigational skills. Their education had also sought to instil the standard British public school behaviour of team, country and King before self. They were avid readers of Boy’s Own Paper and many had belonged to Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout movement. Recognizing this, Christopher Clayton Hutton identified all the available literature, a total of fifty books (through a visit to the British Museum Reading Room) and purchased second-hand copies. He enlisted the support of the Headmaster at Rugby School, his alma mater, who allowed the sixth form to carry out a review of the books. The review was completed in four days, and led directly to Hutton’s decision to make maps a priority, for it would appear difficult, if not impossible, to escape from enemy-occupied territory without a map. It was this simple fact which appeared to be the catalyst for Hutton’s visit to the War Office Map Room. The staff there could not apparently help in meeting his initial request for a small-scale map of Germany.

The section responsible for operational maps and geographic matters, MI4, was by that time located in Cheltenham. It had moved from London in September 1939, apparently to make space to accommodate those branches whose presence in Whitehall was deemed to be essential and also to afford protection from possible air attacks to the sizable map collection which was also relocated to Cheltenham. Brigadier A. B. Clough, in his history of the military survey organizations during World War II, Maps and Survey, published in 1952, made it clear that the absence of MI4 from London ‘had the serious effect of putting it out of daily touch with the General Staff at a critical period’. MI4 remained physically distanced from all War Office operations, intelligence and planning staff and also from the Air Ministry Map Section, which had been moved to Harrow. It is, therefore, likely that the War Office Map Room visited by Hutton was simply a small reference collection and not the main operational map collection of MI4 which would certainly have held the maps he sought. Hutton’s lack of contact with the military map-makers is likely to have been to the longer term detriment of the escape and evasion mapping programme.

During a visit to the commercial mapping company, Geographia Limited, on London’s Fleet Street, he discovered the existence of ‘a famous Scottish firm’ which proved to be John Bartholomew & Son Ltd of Edinburgh. This renowned cartographic company was established in 1826 by John Bartholomew, built on his and his father’s experiences as apprentices to the Edinburgh engravers, Lizars, from the last years of the eighteenth century. By the late nineteenth century it had acquired a world-wide reputation for its maps. Hutton was also fortunate that the firm was headed at the time by John (known as Ian) Bartholomew who had had a distinguished military career in World War I, serving as an officer in the First Battalion, Gordon Highlanders, experiencing the worst of trench warfare and winning the Military Cross at Ypres in 1915.

Ian Bartholomew was only too ready to hand over copies of his company’s maps, waiving all copyright and insisting ‘it was a privilege to contribute to the war effort’. This was to prove the critical ingredient to MI9’s wartime escape and evasion mapping programme. It was this collection of small-scale maps of Europe, the Middle East and Africa which provided the backbone of the escape and evasion mapping which MI9 subsequently produced. At the time, the company was not aware of its wartime involvement with MI9, a secret which Ian Bartholomew, the Managing Director, apparently never even mentioned to his sons.