По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

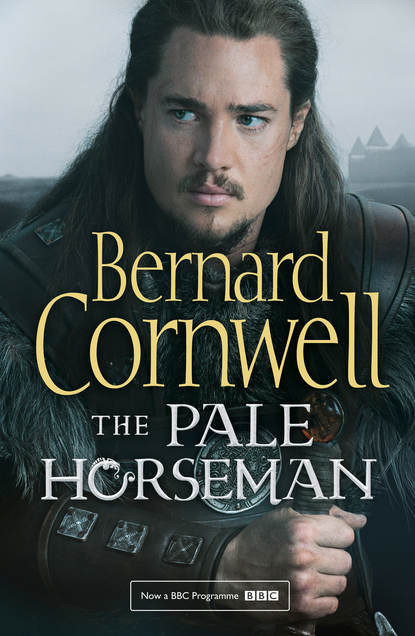

The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In the winter, while I was mewed up in Werham as one of the hostages given to Guthrum, a new law had been passed in Wessex, a law which decreed that no man other than the royal bodyguards was to draw a weapon in the presence of the king. The law was not just to protect Alfred, but also to prevent the quarrels between his great men becoming lethal and, by drawing Serpent-Breath, I had unwittingly broken the law so that his household troops were suddenly converging on me with spears and drawn swords until Alfred, red-cloaked and bare-headed, shouted for every man to be still.

Then he walked towards me and I could see the anger on his face. He had a narrow face with a long nose and chin, a high forehead, and a thin-lipped mouth. He normally went clean-shaven, but he had grown a short beard that made him look older. He had not lived thirty years yet, but looked closer to forty. He was painfully thin, and his frequent illnesses had given his face a crabbed look. He looked more like a priest than the king of the West Saxons, for he had the irritated, pale face of a man who spends too much time out of the sun and poring over books, but there was an undoubted authority in his eyes. They were very light eyes, as grey as mail, unforgiving. ‘You have broken my peace,’ he said, ‘and offended the peace of Christ.’

I sheathed Serpent-Breath, mainly because Beocca had muttered at me to stop being a damned fool and to put my sword away, and now the priest was tugging my right leg, trying to make me dismount and kneel to Alfred, whom he adored. Ælswith, Alfred’s wife, was staring at me with pure scorn. ‘He should be punished,’ she called out.

‘You will go there,’ the king said, pointing towards one of his tents, ‘and wait for my judgment.’

I had no choice but to obey, for his household troops, all of them in mail and helmets, pressed about me and so I was taken to the tent where I dismounted and ducked inside. The air smelled of yellowed, crushed grass. The rain pattered on the linen roof and some leaked through onto an altar that held a crucifix and two empty candle-holders. The tent was evidently the king’s private chapel and Alfred made me wait there a long time. The congregation dispersed, the rain ended and a watery sunlight emerged between the clouds. A harp played somewhere, perhaps serenading Alfred and his wife as they ate. A dog came into the tent, looked at me, lifted its leg against the altar and went out again. The sun vanished behind cloud and more rain pattered on the canvas, then there was a flurry at the tent’s opening and two men entered. One was Æthelwold, the king’s nephew, and the man who should have inherited Wessex’s throne from his father except he had been reckoned too young and so the crown had gone to his uncle instead. He gave me a sheepish grin, deferring to the second man who was heavy-set, full-bearded and ten years older than Æthelwold. He introduced himself by sneezing, then blew his nose into his hand and wiped the snot onto his leather coat. ‘Call it springtime,’ he grumbled, then stared at me with a truculent expression. ‘Damned rain never stops. You know who I am?’

‘Wulfhere,’ I said, ‘Ealdorman of Wiltunscir.’ He was a cousin to the king and a leading power in Wessex.

He nodded. ‘And you know who this damn fool is?’ he asked, gesturing at Æthelwold who was holding a bundle of white cloth.

‘We know each other,’ I said. Æthelwold was only a month or so younger than I, and he was fortunate, I suppose, that his Uncle Alfred was such a good Christian or else he could have expected a knife in the night. He was much better looking than Alfred, but foolish, flippant and usually drunk, though he appeared sober enough on that Sunday morning.

‘I’m in charge of Æthelwold now,’ Wulfhere said, ‘and of you. And the king sent me to punish you.’ He brooded on that for a heartbeat. ‘What his wife wants me to do,’ he went on, ‘is pull the guts out of your smelly arse and feed them to the pigs.’ He glared at me. ‘You know what the penalty is for drawing a sword in the king’s presence?’

‘A fine?’ I guessed.

‘Death, you fool, death. They made a new law last winter.’

‘How was I supposed to know?’

‘But Alfred’s feeling merciful,’ Wulfhere ignored my question. ‘So you’re not to dangle off a gallows. Not today, anyhow. But he wants your assurance you’ll keep the peace.’

‘What peace?’

‘His damned peace, you fool. He wants us to fight the Danes, not slice each other up. So for the moment you have to swear to keep the peace.’

‘For the moment?’

‘For the moment,’ he said tonelessly, and I just shrugged. He took that for acceptance. ‘So you killed Ubba?’ he asked.

‘I did.’

‘That’s what I hear.’ He sneezed again. ‘You know Edor?’

‘I know him,’ I said. Edor was one of Ealdorman Odda’s battle chiefs, a warrior of the men of Defnascir, and he had fought beside us at Cynuit.

‘Edor told me what happened,’ Wulfhere said, ‘but only because he trusts me. For God’s sake stop fidgeting!’ This last shout was directed at Æthelwold who was poking beneath the altar’s linen cover, presumably in search of something valuable. Alfred, rather than murder his nephew, seemed intent on boring him to death. Æthelwold had never been allowed to fight, lest he make a reputation for himself, instead he had been forced to learn his letters, which he hated, and so he idled his time away, hunting, drinking, whoring and filled with resentment that he was not the king. ‘Just stand still, boy,’ Wulfhere snarled.

‘Edor told you,’ I said, unable to keep the outrage from my voice, ‘because he trusts you? You mean what happened at Cynuit is a secret? A thousand men saw me kill Ubba!’

‘But Odda the Younger took the credit,’ Wulfhere said, ‘and his father is badly wounded and if he dies then Odda the Younger will become one of the richest men in Wessex, and he’ll lead more troops and pay more priests than you can ever hope to do, so men won’t want to offend him, will they? They’ll pretend to believe him, to keep him generous. And the king already believes him, and why shouldn’t he? Odda arrived here with Ubba Lothbrokson’s banner and war axe. He dropped them at Alfred’s feet, then knelt and gave the praise to God, and promised to build a church and monastery at Cynuit, and what did you do? Ride a damned horse into the middle of mass and wave your sword about. Not a clever thing to do with Alfred.’

I half smiled at that, for Wulfhere was right. Alfred was uncommonly pious, and a sure way to succeed in Wessex was to flatter that piety, imitate it and ascribe all good fortune to God.

‘Odda’s a prick,’ Wulfhere growled, surprising me, ‘but he’s Alfred’s prick now, and you’re not going to change that.’

‘But I killed …’

‘I know what you did!’ Wulfhere interrupted me. ‘And Alfred probably suspects you’re telling the truth, but he believes Odda made it possible. He thinks Odda and you both fought Ubba. He may not even care if neither of you did, except that Ubba’s dead and that’s good news, and Odda brought that news and so the sun shines out of Odda’s arse, and if you want the king’s troops to hang you off a high branch then you’ll make a feud with Odda. Do you understand me?’

‘Yes.’

Wulfhere sighed. ‘Leofric said you’d see sense if I beat you over the head long enough.’

‘I want to see Leofric,’ I said.

‘You can’t,’ Wulfhere said sharply. ‘He’s being sent back to Hamtun where he belongs. But you’re not going back. The fleet will be put in someone else’s charge. You’re to do penance.’

For a moment I thought I had misheard. ‘I’m to do what?’ I asked.

‘You’re to grovel,’ Æthelwold spoke for the first time. He grinned at me. We were not exactly friends, but we had drunk together often enough and he seemed to like me. ‘You’re to dress like a girl,’ Æthelwold continued, ‘go on your knees and be humiliated.’

‘And you’re to do it right now,’ Wulfhere added.

‘I’ll be damned …’

‘You’ll be damned anyway,’ Wulfhere snarled at me, then snatched the white bundle from Æthelwold’s grasp and tossed it at my feet. It was a penitent’s robe, and I left it on the ground. ‘For God’s sake, lad,’ Wulfhere said, ‘have some sense. You’ve got a wife and land here, don’t you? So what happens if you don’t do the king’s bidding? You want to be outlawed? You want your wife in a nunnery? You want the church to take your land?’

I stared at him. ‘All I did was kill Ubba and tell the truth.’

Wulfhere sighed. ‘You’re a Northumbrian,’ he said, ‘and I don’t know how they did things up there, but this is Alfred’s Wessex. You can do anything in Wessex except piss all over his church, and that’s what you just did. You pissed, son, and now the church is going to piss all over you.’ He grimaced as the rain beat harder on the tent, then he frowned, staring at the puddle spreading just outside the entrance. He was silent a long time, before turning and giving me a strange look. ‘You think any of this is important?’

I did, but I was so astonished by his question, which had been asked in a soft, bitter voice, that I had nothing to say.

‘You think Ubba’s death makes any difference?’ he asked, and again I thought I had misheard. ‘And even if Guthrum makes peace,’ he went on, ‘you think we’ve won?’ His heavy face was suddenly savage. ‘How long will Alfred be king? How long before the Danes rule here?’

I still had nothing to say. Æthelwold, I saw, was listening intently. He longed to be king, but he had no following, and Wulfhere had plainly been appointed as his guardian to keep him from making trouble. But Wulfhere’s words suggested the trouble would come anyway. ‘Just do what Alfred wants,’ the ealdorman advised me, ‘and afterwards find a way to keep living. That’s all any of us can do. If Wessex falls we’ll all be looking for a way to stay alive, but in the meantime put on that damned robe and get it over with.’

‘Both of us,’ Æthelwold said, and he picked up the robe and I saw he had fetched two of them, folded together.

‘You?’ Wulfhere snarled at him. ‘Are you drunk?’

‘I’m penitent for being drunk. Or I was drunk, now I’m penitent.’ He grinned at me, then pulled the robe over his head. ‘I shall go to the altar with Uhtred,’ he said, his voice muffled by the linen.

Wulfhere could not stop him, but Wulfhere knew, as I knew, that Æthelwold was making a mockery of the rite. And I knew Æthelwold was doing it as a favour to me, though as far as I knew he owed me no favour. But I was grateful to him, so I put on the damned frock and, side by side with the king’s nephew, went to my humiliation.

I meant little to Alfred. He had a score of great lords in Wessex, while across the frontier in Mercia there were other lords and thegns who lived under Danish rule but who would fight for Wessex if Alfred gave them an opportunity. All of those great men could bring him soldiers, could rally swords and spears to the dragon banner of Wessex, while I could bring him nothing except my sword, Serpent-Breath. True, I was a lord, but I was from far off Northumbria and I led no men and so my only value to him was far in the future. I did not understand that yet. In time, as the rule of Wessex spread northwards, my value grew, but back then, in 877, when I was an angry twenty-year-old, I knew nothing except my own ambitions.

And I learned humiliation. Even today, a lifetime later, I remember the bitterness of that penitential grovel. Why did Alfred make me do it? I had won him a great victory, yet he insisted on shaming me, and for what? Because I had disturbed a church service? It was partly that, but only partly. He loved his god, loved the church and passionately believed that the survival of Wessex lay in obedience to the church and so he would protect the church as fiercely as he would fight for his country. And he loved order. There was a place for everything and I did not fit and he genuinely believed that if I could be brought to God’s heel then I would become part of his beloved order. In short he saw me as an unruly young hound that needed a good whipping before it could join the disciplined pack.

So he made me grovel.

And Æthelwold made a fool of himself.

Not at first. At first it was all solemnity. Every man in Alfred’s army was there to watch, and they made two lines in the rain. The lines stretched to the altar under the guyed sail-cloth where Alfred and his wife waited with the bishop and a gaggle of priests. ‘On your knees,’ Wulfhere said to me. ‘You have to go on your knees,’ he insisted tonelessly, ‘and crawl up to the altar. Kiss the altar cloth, then lie flat.’