По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

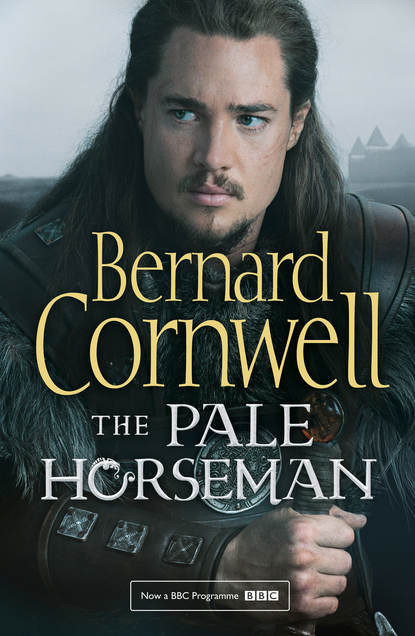

The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You’re my man,’ I said, ‘and you’ll give me an oath, and I’ll give you a sword.’

‘Why?’ he wanted to know.

‘Because a Dane saved me once,’ I said, ‘and I like the Danes.’

I also wanted Haesten because I needed men. I did not trust Odda the Younger, and I feared Steapa Snotor, Odda’s warrior, and so I would have swords at Oxton. Mildrith, of course, did not want sword-Danes at her house. She wanted ploughmen and peasants, milkmaids and servants, but I told her I was a lord, and a lord has swords.

I am indeed a lord, a lord of Northumbria. I am Uhtred of Bebbanburg. My ancestors, who can trace their lineage back to the god Woden, the Danish Odin, were once kings in northern England, and if my uncle had not stolen Bebbanburg from me when I was just ten years old I would have lived there still as a Northumbrian lord safe in his sea-washed fastness. The Danes had captured Northumbria, and their puppet king, Ricsig, ruled in Eoferwic, but Bebbanburg was too strong for any Dane and my uncle Ælfric ruled there, calling himself Ealdorman Ælfric, and the Danes left him in peace so long as he did not trouble them, and I often dreamed of going back to Northumbria to claim my birthright. But how? To capture Bebbanburg I would need an army, and all I had was one young Dane, Haesten.

And I had other enemies in Northumbria. There was Earl Kjartan and his son Sven, who had lost an eye because of me, and they would kill me gladly, and my uncle would pay them to do it, and so I had no future in Northumbria, not then. But I would go back. That was my soul’s wish, and I would go back with Ragnar the Younger, my friend, who still lived because his ship had weathered the storm. I heard that from a priest who had listened to the negotiations outside Exanceaster and he was certain that Earl Ragnar had been one of the Danish lords in Guthrum’s delegation. ‘A big man,’ the priest told me, ‘and very loud.’ That description convinced me that Ragnar lived and my heart was glad for it, for I knew that my future lay with him, not with Alfred. When the negotiations were finished and a truce made, the Danes would doubtless leave Exanceaster and I would give my sword to Ragnar and carry it against Alfred, who hated me. And I hated him.

I told Mildrith that we would leave Defnascir and go to Ragnar, that I would be his man and that I would pursue my bloodfeud against Kjartan and against my uncle under Ragnar’s eagle banner, and Mildrith responded with tears and more tears.

I cannot bear a woman’s crying. Mildrith was hurt and she was confused and I was angry and we snarled at each other like wildcats and the rain kept falling and I raged like a beast in a cage and wished Alfred and Guthrum would finish their talking because everyone knew that Alfred would let Guthrum go, and once Guthrum left Exanceaster then I could join the Danes and I did not care whether Mildrith came or not, so long as my son, who bore my name, went with me. So by day I hunted, at night I drank and dreamed of revenge and then one evening I came home to find Father Willibald waiting in the house.

Willibald was a good man. He had been chaplain to Alfred’s fleet when I commanded those twelve ships, and he told me he was on his way back to Hamtun, but he thought I would like to know what had unfolded in the long talks between Alfred and Guthrum. ‘There is peace, lord,’ he told me, ‘thanks be to God, there is peace.’

‘Thanks be to God,’ Mildrith echoed.

I was cleaning the blood from the blade of a boar spear and said nothing. I was thinking that Ragnar was released from the siege now and I could join him.

‘The treaty was sealed with solemn oaths yesterday,’ Willibald said, ‘and so we have peace.’

‘They gave each other solemn oaths last year,’ I said sourly. Alfred and Guthrum had made peace at Werham, but Guthrum had broken the truce and murdered the hostages he had been holding. Eleven of the twelve had died, and only I had lived because Ragnar was there to protect me. ‘So what have they agreed?’ I asked.

‘The Danes are to give up all their horses,’ Willibald said, ‘and march back into Mercia.’

Good, I thought, because that was where I would go. I did not say that to Willibald, but instead sneered that Alfred was just letting them march away. ‘Why doesn’t he fight them?’ I asked.

‘Because there are too many, lord. Because too many men would die on both sides.’

‘He should kill them all.’

‘Peace is better than war,’ Willibald said.

‘Amen,’ Mildrith said.

I began sharpening the spear, stroking the whetstone down the long blade. It seemed to me that Alfred had been absurdly generous. Guthrum, after all, was the one remaining leader of any stature on the Danish side, and he had been trapped, and if I had been Alfred there would have been no terms, only a siege, and at its end the Danish power in southern England would have been broken. Instead Guthrum was to be allowed to leave Exanceaster. ‘It is the hand of God,’ Willibald said.

I looked at him. He was a few years older than I was, but always seemed younger. He was earnest, enthusiastic and kind. He had been a good chaplain to the twelve ships, though the poor man was ever seasick and blanched at the sight of blood. ‘God made the peace?’ I asked sceptically.

‘Who sent the storm that sank Guthrum’s ships?’ Willibald retorted fervently, ‘who delivered Ubba into our hands?’

‘I did,’ I said.

He ignored that. ‘We have a godly king, lord,’ he said, ‘and God rewards those that serve him faithfully. Alfred has defeated the Danes! And they see it! Guthrum can recognise divine intervention! He has been making enquiries about Christ.’

I said nothing.

‘Our king believes,’ the priest went on, ‘that Guthrum is not far from seeing the true light of Christ.’ He leaned forward and touched my knee. ‘We have fasted, lord,’ he said, ‘we have prayed, and the king believes that the Danes will be brought to Christ and when that happens there will be a permanent peace.’

He meant every word of that nonsense and, of course, it was sweet music to Mildrith’s ears. She was a good Christian and had great faith in Alfred, and if the king believed that his god would bring victory then she would believe it too. It seemed madness to me, but I said nothing as a servant brought us barley ale, bread, smoked mackerel and cheese. ‘We shall have a Christian peace,’ Willibald said, making the sign of the cross above the bread before he ate, ‘sealed by hostages.’

‘We’ve given Guthrum hostages again?’ I asked, astonished.

‘No,’ Willibald said. ‘But he has agreed to give us hostages. Including six earls!’

I stopped sharpening the spear and looked at Willibald. ‘Six earls?’

‘Including your friend, Ragnar!’ Willibald seemed pleased by this news, but I was appalled. If Ragnar was not with the Danes then I could not go to them. He was my friend and his enemies were my enemies, but without Ragnar to protect me I would be horribly vulnerable to Kjartan and Sven, the father and son who had murdered Ragnar’s father and who wanted me dead. Without Ragnar, I knew, I could not leave Wessex.

‘Ragnar’s one of the hostages?’ I asked. ‘You’re sure?’

‘Of course I’m sure. He will be held by Ealdorman Wulfhere. All the hostages are to be held by Wulfhere.’

‘For how long?’

‘For as long as Alfred wishes, or until Guthrum is baptised. And Guthrum has agreed that our priests can talk to his men.’ Willibald gave me a pleading look. ‘We must have faith in God,’ he said. ‘We must give God time to work on the hearts of the Danes. Guthrum understands now that our god has power!’

I stood and went to the door, pulling aside the leather curtain and staring down at the wide sea-reach of the Uisc. I was sick at heart. I hated Alfred, did not want to be in Wessex, but now it seemed I was doomed to stay there. ‘And what do I do?’ I asked.

‘The king will forgive you, lord,’ Willibald said nervously.

‘Forgive me?’ I turned on him. ‘And what does the king believe happened at Cynuit? You were there, father,’ I said, ‘so did you tell him?’

‘I told him.’

‘And?’

‘He knows you are a brave warrior, lord,’ Willibald said, ‘and that your sword is an asset to Wessex. He will receive you again, I’m sure, and he will receive you joyfully. Go to church, pay your debts and show that you are a good man of Wessex.’

‘I’m not a West Saxon,’ I snarled at him, ‘I’m a Northumbrian!’

And that was part of the problem. I was an outsider. I spoke a different English. The men of Wessex were tied by family, and I came from the strange north and folk believed I was a pagan, and they called me a murderer because of Oswald’s death, and sometimes, when I rode about the estate, men would make the sign of the cross to avert the evil they saw in me. They called me Uhtredærwe, which means Uhtred the Wicked, and I was not unhappy with the insult, but Mildrith was. She assured them I was a Christian, but she lied, and our unhappiness festered all that summer. She prayed for my soul, I fretted for my freedom, and when she begged me to go with her to the church at Exanmynster I growled at her that I would never set foot in another church all my days. She would weep when I said that and her tears drove me out of the house to hunt, and sometimes the chase would take me down to the water’s edge where I would stare at Heahengel.

She lay canted on the muddy foreshore, lifted and dropped repeatedly by the tides, abandoned. She was one of Alfred’s fleet, one of the twelve large warships he had built to harry the Danish boats that raided Wessex’s coast, and Leofric and I had brought Heahengel up from Hamtun in pursuit of Guthrum’s fleet and we had survived the storm that sent so many Danes to their deaths and we had beached Heahengel here, left her mastless and without a sail, and she was still on the Uisc’s foreshore, rotting and apparently forgotten.

Archangel. That was what her name meant. Alfred had named her and I had always hated the name. A ship should have a proud name, not a snivelling religious word, and she should have a beast on her prow, high and defiant, a dragon’s head to challenge the sea or a snarling wolf to terrify an enemy. I sometimes climbed on board Heahengel and saw how the local villagers had plundered some of her upper strakes, and how there was water in her belly, and I remembered her proud days at sea and the wind whipping through her seal-hide rigging and the crash as we had rammed a Danish boat.

Now, like me, Heahengel had been left to decay, and sometimes I dreamed of repairing her, of finding new rigging and a new sail, of finding men and taking her long hull to sea. I wanted to be anywhere but where I was, I wanted to be with the Danes, and every time I said that Mildrith would weep again. ‘You can’t make me live among the Danes!’

‘Why not? I did.’

‘They’re pagans! My son won’t grow up a pagan!’

‘He’s my son too,’ I said, ‘and he will worship the gods I worship.’ There would be more tears then, and I would storm out of the house and take the hounds up to the high woods and wonder why love soured like milk. After Cynuit I had so wanted to see Mildrith, yet now I could not abide her misery and piety and she could not endure my anger. All she wanted me to do was till my fields, milk my cows and gather my harvest to pay the great debt she had brought me in marriage. That debt came from a pledge made by Mildrith’s father, a pledge to give the church the yield of almost half his land. That pledge was for all time, binding on his heirs, but Danish raids and bad harvests had ruined him. Yet the church, venomous as serpents, still insisted that the debt be paid, and said that if I could not pay then our land would be taken by monks, and every time I went to Exanceaster I could sense the priests and monks watching me and enjoying the prospect of their enrichment. Exanceaster was English again, for Guthrum had handed over the hostages and gone north so that peace of a sort had come to Wessex. The fyrds, the armies of each shire, had been disbanded and sent back to their farms. Psalms were being sung in all the churches and Alfred, to mark his victory, was sending gifts to every monastery and nunnery. Odda the Younger, who was being celebrated as the champion of Wessex, had been given all the land about the place where the battle had been fought at Cynuit and he had ordered a church to be built there, and it was rumoured that the church would have an altar of gold as thanks to God for allowing Wessex to survive.

Though how long would it survive? Guthrum lived and I did not share the Christian belief that God had sent Wessex peace. Nor was I the only one, for in midsummer Alfred returned to Exanceaster where he summoned his Witan, a council of the kingdom’s leading thegns and churchmen, and Wulfhere of Wiltunscir was one of the men summoned and I went into the city one evening and was told the ealdorman and his followers had lodgings in The Swan, a tavern by the east gate. He was not there, but Æthelwold, Alfred’s nephew, was doing his best to drain the tavern of ale. ‘Don’t tell me the bastard summoned you to the Witan?’ he greeted me sourly. The ‘bastard’ was Alfred who had snatched the throne from the young Æthelwold.