По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

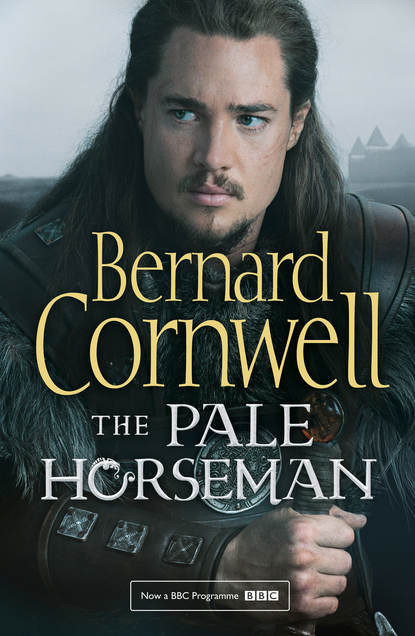

The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Then what?’

‘Then God and the king forgive you,’ he said, and waited. ‘Just do it,’ he snarled.

So I did it. I went down on my knees and I shuffled through the mud, and the silent lines of men watched me, and then Æthelwold, close beside me, began to wail that he was a sinner. He threw his arms in the air, fell flat on his face, howled that he was penitent, shrieked that he was a sinner, and at first men were embarrassed and then they were amused. ‘I’ve known women!’ Æthelwold shouted at the rain, ‘and they were bad women! Forgive me!’

Alfred was furious, but he could not stop a man making a fool of himself before God. Perhaps he thought Æthelwold’s remorse was genuine? ‘I’ve lost count of the women!’ Æthelwold shouted, then beat his fists in the mud. ‘Oh God, I love tits! God, I love naked women, God, forgive me for that!’ The laughter spread, and every man must have remembered that Alfred, before piety caught him in its clammy grip, had been notorious for the women he had pursued. ‘You must help me, God!’ Æthelwold cried as we shuffled a few feet farther. ‘Send me an angel!’

‘So you can hump her?’ a voice called from the crowd and the laughter became a roar.

Ælswith was hurried away, lest she hear something unseemly. The priests whispered together, but Æthelwold’s penitence, though extravagant, seemed real enough. He was weeping. I knew he was really laughing, but he howled as though his soul was in agony. ‘No more tits, God!’ he called, ‘no more tits!’ He made a fool of himself, but, as men already thought him a fool, he did not mind. ‘Keep me from tits, God!’ he shouted, and now Alfred left, knowing that the solemnity of the day was ruined, and most of the priests left with him, so that Æthelwold and I crawled to an abandoned altar where Æthelwold turned in his mud-spattered robe and leaned against the table. ‘I hate him,’ he said softly, and I knew he referred to his uncle. ‘I hate him,’ he went on, ‘and now you owe me a favour, Uhtred.’

‘I do,’ I said.

‘I’ll think of one,’ he said.

Odda the Younger had not left with Alfred. He seemed bemused. My humiliation, which he had surely thought to enjoy, had turned into laughter and he was aware that men were watching him, judging his truthfulness, and he moved closer to a huge man who was evidently one of his bodyguards. That man was tall and very broad about the chest, but it was his face that commanded attention for it looked as though his skin had been stretched too tight across his skull, leaving his face incapable of making any expression other than one of pure hatred and wolfish hunger. Violence came off the man like the stench of a wet hound and when he looked at me it was like a beast’s soulless stare, and I instinctively understood that this was the man who would kill me if Odda found a chance to commit murder. Odda was nothing, a rich man’s spoiled son, but his money gave him the means to command men who were killers. Then Odda plucked at the tall man’s sleeve and they both turned and walked away.

Father Beocca had stayed by the altar. ‘Kiss it,’ he ordered me, ‘then lie flat.’

I stood up instead. ‘You can kiss my arse, father,’ I said. I was angry, and my anger frightened Beocca who backed away.

But I had done what the king wanted. I had been penitent.

The tall man beside Odda the Younger was named Steapa. Steapa Snotor, men called him, or Steapa the Clever. ‘It’s a joke,’ Wulfhere told me as I ripped off the penitent’s frock and pulled on my mail coat.

‘A joke?’

‘Because he’s dumb as an ox,’ Wulfhere said. ‘He’s got frog spawn instead of a brain. He’s stupid, but he’s not a stupid fighter. You didn’t see him at Cynuit?’

‘No,’ I said curtly.

‘So what’s Steapa to you?’ Wulfhere asked.

‘Nothing,’ I said. I had asked the ealdorman who Odda’s bodyguard was so that I could learn the name of the man who might try to kill me, but that possible murder was none of Wulfhere’s business.

Wulfhere hesitated, wanting to ask more, then deciding he would fetch no better answer. ‘When the Danes come,’ he said, ‘you’ll be welcome to join my men.’

Æthelwold, Alfred’s nephew, was holding my two swords and he drew Serpent-Breath from her scabbard and stared at the wispy patterns in her blade. ‘If the Danes come,’ he spoke to Wulfhere, ‘you must let me fight.’

‘You don’t know how to fight.’

‘Then you must teach me.’ He slid Serpent-Breath back into the scabbard. ‘Wessex needs a king who can fight,’ he said, ‘instead of pray.’

‘You should watch your tongue, lad,’ Wulfhere said, ‘in case it gets cut out.’ He snatched the swords from Æthelwold and gave them to me. ‘The Danes will come,’ he said, ‘so join me when they do.’

I nodded, but said nothing. When the Danes came, I thought, I planned to be with them. I had been raised by Danes after being captured at the age of ten and they could have killed me, but instead they had treated me well. I had learned their language and worshipped their gods until I no longer knew whether I was Danish or English. Had Earl Ragnar the Elder lived I would never have left them, but he had died, murdered in a night of treachery and fire, and I had fled south to Wessex. But now I would go back. Just as soon as the Danes left Exanceaster I would join Ragnar’s son, Ragnar the Younger, if he lived. Ragnar the Younger’s ship had been in the fleet which had been hammered in the great storm. Scores of ships had sunk, and the remnants of the fleet had limped to Exanceaster where the boats were now burned to ash on the riverbank beneath the town. I did not know if Ragnar lived. I hoped he lived, and I prayed he would escape Exanceaster and then I would go to him, offer him my sword, and carry that blade against Alfred of Wessex. Then, one day, I would dress Alfred in a frock and make him crawl on his knees to an altar of Thor. Then kill him.

Those were my thoughts as we rode to Oxton. That was the estate Mildrith had brought me in marriage and it was a beautiful place, but so saddled with debt that it was more of a burden than a pleasure. The farmland was on the slopes of hills facing east towards the broad sea-reach of the Uisc and above the house were thick woods of oak and ash from which flowed small clear streams that cut across the fields where rye, wheat and barley grew. The house, it was not a hall, was a smoke-filled building made from mud, dung, oak and rye-straw, and so long and low that it looked like a green, moss-covered mound from which smoke escaped through the roof’s central hole. In the attached yard were pigs, chickens and mounds of manure as big as the house. Mildrith’s father had farmed it, helped by a steward named Oswald who was a weasel, and he caused me still more trouble on that rainy Sunday as we rode back to the farm.

I was furious, resentful and vengeful. Alfred had humiliated me which made it unfortunate for Oswald that he had chosen that Sunday afternoon to drag an oak tree down from the high woods. I was brooding on the pleasures of revenge as I let my horse pick its way up the track through the trees and saw eight oxen hauling the great trunk towards the river. Three men were goading the oxen, while a fourth, Oswald, rode the trunk with a whip. He saw me and jumped off and, for a heartbeat, it looked as if he wanted to run into the trees, but then he realised he could not evade me and so he just stood and waited as I rode up to the great oak log.

‘Lord,’ Oswald greeted me. He was surprised to see me. He probably thought I had been killed with the other hostages, and that belief had made him careless.

My horse was nervous because of the stink of blood from the oxen’s flanks and he stepped backwards and forwards in small steps until I calmed him by patting his neck. Then I looked at the oak trunk that must have been forty feet long and as thick about as a man is tall. ‘A fine tree,’ I said to Oswald.

He glanced towards Mildrith who was twenty paces away. ‘Good day, lady,’ he said, clawing off the woollen hat he wore over his springy red hair.

‘A wet day, Oswald,’ she said. Her father had appointed the steward and Mildrith had an innocent faith in his reliability.

‘I said,’ I spoke loudly, ‘a fine tree. So where was it felled?’

Oswald tucked the hat into his belt. ‘On the top ridge, lord,’ he said vaguely.

‘The top ridge on my land?’

He hesitated. He was doubtless tempted to claim it came from a neighbour’s land, but that lie could easily have been exposed and so he said nothing.

‘From my land?’ I asked again.

‘Yes, lord,’ he admitted.

‘And where is it going?’

He hesitated again, but had to answer. ‘Wigulf’s mill.’

‘Wigulf buys it?’

‘He’ll split it, lord.’

‘I didn’t ask what he will do with it,’ I said, ‘but whether he will buy it.’

Mildrith, hearing the harshness in my voice, intervened to say that her father had sometimes sent timber to Wigulf’s mill, but I waved her to silence. ‘Will he buy it?’ I asked Oswald.

‘We need the timber, lord, to make repairs,’ the steward said, ‘and Wigulf takes his fee in split wood.’

‘And you drag the tree on a Sunday?’ He had nothing to say to that. ‘Tell me,’ I went on, ‘if we need planks for repairs, then why don’t we split the trunk ourselves? Do we lack men? Or wedges? Or mauls?’

‘Wigulf has always done it,’ Oswald said in a surly tone.

‘Always?’ I repeated and Oswald said nothing. ‘Wigulf lives in Exanmynster?’ I guessed. Exanmynster lay a mile or so northwards and was the nearest settlement to Oxton.

‘Yes, lord,’ Oswald said.

‘So if I ride to Exanmynster now,’ I said, ‘Wigulf will tell me how many similar trees you’ve delivered to him in the last year?’

There was silence, except for the rain dripping from leaves and the intermittent burst of birdsong. I edged my horse a few steps closer to Oswald, who gripped his whip’s handle as if readying it to lash out at me. ‘How many?’ I asked.

Oswald said nothing.