По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

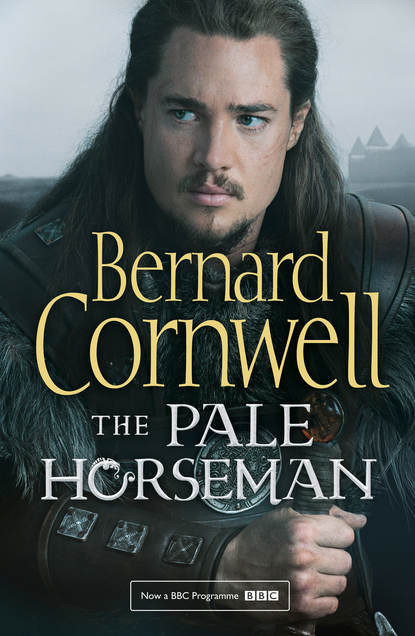

The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That God has sent us peace.’

Wulfhere laughed at my mockery. ‘Guthrum’s in Gleawecestre,’ he said, ‘and that’s just a half day’s march from our frontier. And they say more Danish ships arrive every day. They’re in Lundene, they’re in the Humber, they’re in the Gewæsc.’ He scowled. ‘More ships, more men, and Alfred’s building churches! And there’s this fellow Svein.’

‘Svein?’

‘Brought his ships from Ireland. Bastard’s in Wales now, but he won’t stay there, will he? He’ll come to Wessex. And they say more Danes are joining him from Ireland.’ He brooded on this bad news. I did not know whether it was true, for such rumours were ever current, but Wulfhere plainly believed it. ‘We should march on Gleawecestre,’ he said, ‘and slaughter the lot of them before they slaughter us, but we’ve got a kingdom ruled by priests.’

That was true, I thought, just as it was certain that Wulfhere would not make it easy for me to see Ragnar. ‘Will you give a message to Ragnar?’ I asked.

‘How? I don’t speak Danish. I could ask the priest, but he’ll tell Alfred.’

‘Does Ragnar have a woman with him?’ I asked.

‘They all do.’

‘A thin girl,’ I said, ‘black hair. Face like a hawk.’

He nodded cautiously. ‘Sounds right. Has a dog, yes?’

‘She has a dog,’ I said, ‘and its name is Nihtgenga.’

He shrugged as if he did not care what the dog was called, then he understood the significance of the name. ‘An English name?’ he asked. ‘A Danish girl calls her dog Goblin?’

‘She isn’t Danish,’ I said. ‘Her name is Brida, and she’s a Saxon.’

He stared at me, then laughed. ‘The cunning little bitch. She’s been listening to us, hasn’t she?’

Brida was indeed cunning. She had been my first lover, an East Anglian girl who had been raised by Ragnar’s father and who now slept with Ragnar. ‘Talk to her,’ I said, ‘and give her my greetings, and say that if it comes to war …’ I paused, not sure what to say. There was no point in promising to do my best to rescue Ragnar, for if war came then the hostages would be slaughtered long before I could reach them.

‘If it comes to war?’ Wulfhere prompted me.

‘If it comes to war,’ I said, repeating the words he had spoken to me before my penance, ‘we’ll all be looking for a way to stay alive.’

Wulfhere stared at me for a long time and his silence told me that though I had failed to find a message for Ragnar I had given a message to Wulfhere. He drank ale. ‘So the bitch speaks English, does she?’

‘She’s a Saxon.’

As was I, but I hated Alfred and I would join Ragnar when I could, if I could, whatever Mildrith wanted, or so I thought. But deep under the earth, where the corpse serpent gnaws at the roots of Yggdrasil, the tree of life, there are three spinners. Three women who make our fate. We might believe we make choices, but in truth our lives are in the spinners’ fingers. They make our lives, and destiny is everything. The Danes know that, and even the Christians know it. Wyrd bið ful aræd, we Saxons say, fate is inexorable, and the spinners had decided my fate because, a week after the Witan had met, when Exanceaster was quiet again, they sent me a ship.

The first I knew of it was when a slave came running from Oxton’s fields saying that there was a Danish ship in the estuary of the Uisc and I pulled on boots and mail, snatched my swords from their peg, shouted for a horse to be saddled and rode to the foreshore where Heahengel rotted.

And where, standing in from the long sandspit that protects the Uisc from the greater sea, another ship approached. Her sail was furled on the long yard and her dripping oars rose and fell like wings and her long hull left a spreading wake that glittered silver under the rising sun. Her prow was high, and standing there was a man in full mail, a man with a helmet and spear, and behind me, where a few fisherfolk lived in hovels beside the mud, people were hurrying towards the hills and taking with them whatever few possessions they could snatch. I called to one of them. ‘It’s not a Dane!’

‘Lord?’

‘It’s a West Saxon ship,’ I called, though they did not believe me and hurried away with their livestock. For years they had done this. They would see a ship and they would run, for ships brought Danes and Danes brought death, but this ship had no dragon or wolf or eagle’s head on its prow. I knew the ship. It was the Eftwyrd, the best named of all Alfred’s ships which otherwise bore pious names like Heahengel or Apostol or Cristenlic. Eftwyrd meant judgement day which, though Christian in inspiration, accurately described what she had brought to many Danes.

The man in the prow waved and, for the first time since I had crawled on my knees to Alfred’s altar, my spirits lifted. It was Leofric, and then the Eftwyrd’s bows slid onto the mud and the long hull juddered to a halt. Leofric cupped his hands. ‘How deep is this mud?’

‘It’s nothing!’ I shouted back, ‘a hand’s depth, no more!’

‘Can I walk on it?’

‘Of course you can!’ I shouted back.

He jumped and, as I had known he would, sank up to his thighs in the thick black slime, and I bent over my saddle’s pommel in laughter, and the Eftwyrd’s crew laughed with me as Leofric cursed, and it took ten minutes to extricate him from the muck, by which time a score of us were plastered in the stinking stuff, but then the crew, who were mostly my old oarsmen and warriors, brought ale ashore, and bread and salted pork, and we made a midday meal beside the rising tide.

‘You’re an earsling,’ Leofric grumbled, looking at the mud clogging up the links of his mail coat.

‘I’m a bored earsling,’ I said.

‘You’re bored?’ Leofric said, ‘so are we.’ It seemed the fleet was not sailing. It had been given into the charge of a man named Burgweard who was a dull, worthy soldier whose brother was bishop of Scireburnan, and Burgweard had orders not to disturb the peace. ‘If the Danes aren’t off the coast,’ Leofric said, ‘then we aren’t.’

‘So what are you doing here?’

‘He sent us to rescue that piece of shit,’ he nodded at Heahengel. ‘He wants twelve ships again, see?’

‘I thought they were building more?’

‘They were building more, only it all stopped because some thieving bastards stole the timber while we were fighting at Cynuit, and then someone remembered Heahengel and here we are. Burgweard can’t manage with just eleven.’

‘If he isn’t sailing,’ I asked, ‘why does he want another ship?’

‘In case he has to sail,’ Leofric explained, ‘and if he does then he wants twelve. Not eleven, twelve.’

‘Twelve? Why?’

‘Because,’ Leofric paused to bite off a piece of bread, ‘because it says in the gospel book that Christ sent out his disciples two by two, and that’s how we have to go, two ships together, all holy, and if we’ve only got eleven then that means we’ve only got ten, if you follow me.’

I stared at him, not sure whether he was jesting. ‘Burgweard insists you sail two by two?’

Leofric nodded. ‘Because it says so in Father Willibald’s book.’

‘In the gospel book?’

‘That’s what Father Willibald tells us,’ Leofric said with a straight face, then saw my expression and shrugged. ‘Honest! And Alfred approves.’

‘Of course he does.’

‘And if you do what the gospel book tells you,’ Leofric said, still with a straight face, ‘then nothing can go wrong, can it?’

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘So you’re here to rebuild Heahengel?’

‘New mast,’ Leofric said, ‘new sail, new rigging, patch up those timbers, caulk her, then tow her back to Hamtun. It could take a month!’

‘At least.’

‘And I never was much good at making things. Good at fighting, I am, and I can drink ale as well as any man, but I was never much good with a mallet and wedge or with adzes. They are.’ He nodded at a group of a dozen men who were strangers to me.