По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

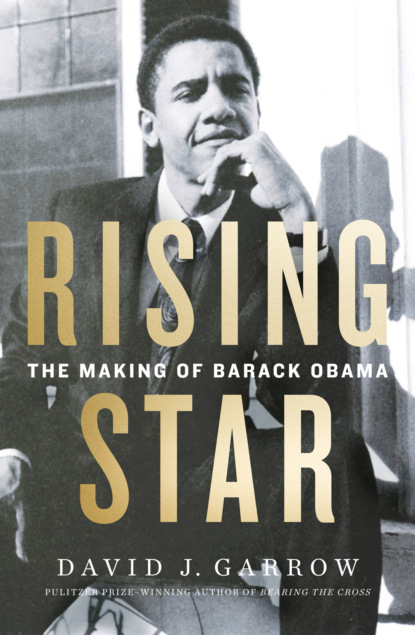

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Eight or ten weeks in advance of Punahou’s June 2, 1979, graduation ceremony, seniors had to submit whatever they wanted published on the one-quarter page they would each have in the 1979 Oahuan. Mark Bendix’s would contain sketches of his VW bus, the “choom van,” and the Koolaus mountain range above Pearl City, plus a “thanks for everything” to classmates whose initials readily translate into their full names: Barry Obama, Kenji Salz, Joe Hansen, Greg Orme, Russ Cunningham, Tom Topolinski, Wayne Weightman, Mark Hebing, and others. Russ Cunningham’s page featured a trio of small photos of Barry, Kenji, and Greg, and “Special Thanks to Friends, Family, Choom Gang.” Both Hebs’s and Topo’s were free of any such allusions, but Orme’s read, “Many thanks to all my friends. Especially the Choom Gang,” with initials for Bendix, Barry, Hansen—who had left school—Kenji, and Cunningham. Kenji’s featured a photo that included Barry and captioned “Ooooochoom Gangooooooo”; his acknowledgments included Bendix, Orme, Barry, Hansen, Cunningham, Hebs, and Weightman. Wayne’s featured the slogan “Fellow students: it’s time to choom!” and a reference to “Pumping station blues.”

Barry Obama’s quarter-page was by far the most striking of all.

Its upper-right corner featured a handsome photo of Barry in a jacket and wide-collared shirt that could have been borrowed from the 1977 dance film Saturday Night Fever. At upper left was a picture of a happy, smiling Obama on a basketball court, captioned “we go play hoop.” At the bottom was a photograph labeled “still life” that included a beer bottle, a record turntable, a telephone, and rolling papers. In the middle was Barry’s chosen message: “Thanks Tut, Gramps, Choom Gang, and Ray for all the good times.”

Decades later, that sentence would receive far less public attention and discussion than it should have. Barry, alone of all the Choom Gang, had singled out their weird, gay, porn-showing drug dealer by name and thanked him “for all the good times.” As Tom Topo most frankly acknowledged, the Choom Gangers had spent plenty of time with Gay Ray over the previous two years, but a public—and permanent—thank-you to their drug connection was something that all the others, even Mark Bendix, did not go so far as to put into print.

Although decades would pass before Obama would learn of his fate, on New Year’s Day 1986, a sleeping thirty-seven-year-old Ray Boyer was bludgeoned to death with a hammer by an angry twenty-year-old male prostitute in an apartment less than two blocks south of 1617 South Beretania Street.

Several days in advance of the graduation ceremony, Ann Dunham returned to Honolulu from Indonesia for the first time in a year. In late 1978, she had completed her fieldwork for her dissertation but, low on funds, had taken a well-paying job with a USAID contractor, Development Alternatives Inc. Based in the Central Java city of Semarang, the job came with a house, servants, and a driver. She and Lolo were on the verge of formally divorcing, and, staying once again at Alice Dewey’s home, she soon would adopt Dewey’s suggestion that she keep Soetoro as her surname rather than revert to Dunham. But she also made a change from Lolo’s colonial Dutch spelling to the Indonesian “Sutoro.”

Preparations for the Saturday-night commencement required extensive choral rehearsals on the part of the entire graduating class. Punahou’s senior prom took place the night before, Friday, June 1. Greg Orme and his steady girlfriend, red-headed Kelli McCormack, hosted Barry and his date, Megan Hughes, a student at La Pietra School for Girls near Diamond Head, for champagne at her family’s home before the two couples headed to the dance and then an after-party. Decades later Kelli would describe Barry and Greg as “like brothers” and described Barry as “very intelligent and witty.” Megan’s presence that evening was the first time Kelli had seen Barry with a date, but in Kelli’s memory, Megan was “gorgeous…. She had the face of an angel and the body of a goddess.” But Barry’s relationship with her was short-lived. In 1983 Megan would have a brief appearance in one episode of the television series Magnum, P.I., which was filmed on Oahu. A decade later Hughes would appear as Terence Stamp’s girlfriend in a movie called The Real McCoy, starring Kim Basinger. Two years later Megan had her own starring role in an R-rated “erotic adventure” film titled Smooth Operator, but her topless appearance failed to make the movie a popular or commercial success.

Yet in 1979, with Orme already scheduled to be away from Hawaii that summer, Barry betrayed more than a hint of desire for his best friend’s girl in the message he wrote in Kelli’s yearbook. “It has been so nice getting to know you this year. You are extremely sweet and foxy. I don’t know why Greg would want to spend any time with me at all! You really deserve better than clowns like us; you even laugh at my jokes! I hope we can keep in touch this summer, even though Greg will be away.” Inscribing his grandparents’ phone number, Barry encouraged Kelli to “Call me up and I’ll buy you lunch … good luck in everything you do, and stay happy. Your friend, Love, Barry Obama.” McCormack soon broke up with Orme, and she did like Barry. “He and I really clicked. We had great vibes between us,” she recounted years later. But she never called him that summer.

On Saturday evening, June 2, Punahou’s 412 graduating seniors, all dressed in matching blazers for the men and long dresses for the women, filed into Honolulu’s Blaisdell Arena, where three months earlier Barry’s AA basketball team had won their championship. A prayer opened the ceremony, followed by the entire class singing a school song. Three seniors—Byron Leong, Annabelle Okada, and class president Dennis Bader—had major speaking roles, interspersed among four more choral selections. Bader’s impressive remarks, in which he told his classmates to follow “your pilot light,” drew prolonged applause from the families and friends seated on the arena’s main floor. Class dean Paula Miyashiro welcomed the graduates, and Academy principal Win Healy invoked his personal tradition of choosing one adjective to describe each year’s class. Commending the 1979 graduates for making 1978–79 “the smoothest and best year of the 1970s” at Punahou, he said the best word to describe them was “harmonic.” President Rod McPhee commended Paula Miyashiro on her “great job” with the class, and then presented each of the graduates with their diploma. As the ceremony was ending, Barry ran into his former Baskin-Robbins coworker Kent Torrey. “Kent, I’ve got to tell you, your dad was one major S.O.B. of a teacher, but at least I learned something from him” in junior-year U.S. history. “What a cool, backhanded compliment from one of the bigger jocks on campus,” Kent thought.

Several of Barry’s friends remember a cohosted graduation party at Kenji Salz’s family’s home with Stan Dunham serving as greeter. “Gramps” was “a great guy” who would always “make sure everybody’s being included,” Greg Ramos remembered. None of Barry’s friends have any clear recollections of Ann Dunham from that weekend. Some, like Mike Ramos and Dan Hale, believe they met her then or at some other time, but as Mike put it, “she lived in Indonesia” and “was just in and out” when visiting Honolulu. Mike’s brother Greg knows he never met her. “She was not a part of his life” during those final years at Punahou. “His grandparents raised him.”

Ann remained in Honolulu for five weeks before returning to Indonesia. Early that summer, Barry hoped to get a job at a pizza parlor—not Mama Mia’s with Gay Ray—and Mark Hebing gave him a ride to the interview. But Barry quickly came back out. The place served beer, and Barry was still two months shy of being eighteen—too young to serve beer if not to drink it. Barry sent eighteen-year-old Hebs in, and he was hired. Barry later recalled making $4 an hour painting instead and also working as a waiter at an assisted-living facility.

By the time of his Punahou graduation, Barry knew that in the fall he would be attending Occidental College in Los Angeles—more precisely, in a far northeastern neighborhood called Eagle Rock, close to the small city of Pasadena. Obama later once half-claimed he chose “Oxy” because he had met some girl on vacation in Honolulu who was from Brentwood—far on the opposite side of sprawling Los Angeles—but the choice may also have been influenced by the hope that he was good enough to play college basketball. Punahou teammate Dan Hale remembers that Barry “really wanted to play college basketball” and as of spring 1979, he believed he “had an opportunity to play there” on an NCAA Division III team.

Occidental recruiter Kraig King, a 1977 Oxy graduate who had combined a stellar academic record with four years of standout play as a starter on Oxy’s varsity basketball team, had visited Punahou back in mid-November 1978, at the same time that Barry was doing so well in Occidental graduate Ian Mattoch’s Law and Society class. Obama later publicly thanked Paula Miyashiro Kurashige as “my dean who got me into college,” and Greg Ramos has a clear memory of Barry being disappointed at how his college applications had turned out. Oxy “was clearly a second choice for him,” especially with another basketball teammate, Darin Maurer, headed to Stanford. Years later Obama said that Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania also rejected him. Oxy required two letters of recommendation; might one from an alumnus who could testify that Barry’s A- in Law and Society was a better predictor of his academic potential than the rest of his Punahou transcript have been decisive? If so, no copy survives.

One afternoon in early September 1979, just a few days before Obama was leaving for Occidental, he paid another visit to grandfatherly Frank Marshall Davis. Frank asked him what he expected to get out of college, and Barry, at least as he later recounted their conversation, replied that he didn’t know.

“That’s the problem, isn’t it? You don’t know. … All you know is that college is the next thing you’re supposed to do.” But Frank had a warning. “Understand something, boy. You’re not going to college to get educated. You’re going there to get trained. They’ll train you to want what you don’t need. They’ll train you to manipulate words so they don’t mean anything anymore. They’ll train you to forget what you already know. They’ll train you so good, you’ll start believing what they tell you about equal opportunity and the American way and all that shit. They’ll give you a corner office and invite you to fancy dinners, and tell you you’re a credit to your race. Until you want to actually start running things, and then they’ll yank on your chain and let you know that you may well be a well-trained, well-paid nigger, but you’re a nigger just the same.”

Barry was confused. Was Frank saying he shouldn’t be going to college? Frank sighed. “No. I didn’t say that. You’ve got to go. I’m just telling you to keep your eyes open. Stay awake.” With those words of paternal advice, the only African American adult eighteen-year-old Barry Obama had ever known bid him farewell for the West Coast mainland.

Chapter Three (#ulink_c83709dd-f69f-5cef-abac-4d01a9b37cbc)

SEARCHING FOR HOME (#ulink_c83709dd-f69f-5cef-abac-4d01a9b37cbc)

EAGLE ROCK, MANHATTAN, BROOKLYN, AND HERMITAGE, PA

SEPTEMBER 1979–JULY 1985

Eighteen-year-old Barry Obama arrived on Occidental College’s campus in Los Angeles’s far northeastern Eagle Rock neighborhood on Sunday, September 16, 1979. Upon arrival, he learned that his dormitory assignment was Haines Hall Annex, room A104, a small, three-man “triple.” Oxy, as everyone called it, had expected 425 entering freshmen but, on the day before Obama arrived, the number hit 434 before growing to 458. Of them, 243 were men and 215 were women. The students noted the unexpectedly tight quarters, but college officials were overjoyed, because for several years Oxy had been having a hard time both attracting and retaining academically qualified undergraduates.

Eighteen months earlier, college president Richard C. Gilman had told the faculty that the freshman class target was being reduced from 450 to 425 because for the last three or four years “admission had been offered to every qualified applicant,” Oxy’s student newspaper reported. Gilman confessed that some who were admitted “may not have been fully qualified.” Out of 1,124 applicants for the class of 1980, only 179 had been refused admission. To raise Oxy’s standards, a new dean of admissions and new staff were hired in mid-1977, but as of 1978 only 54.2 percent of students admitted to the previous four graduating classes had graduated in the normal four years. The class of 1980 was distinguished by the number of dropouts and students transferring to larger institutions. Oxy’s student newspaper interviewed sophomores about their plans, and in a front-page story reported that “it seems that at least half of them are not planning to return next year.” The “primary complaint is that the college is too small and limited” academically; other issues were “the limited social atmosphere, the immaturity of the student body and the lack of privacy on campus.”

Privacy didn’t get any easier with the advent of three-person triples, and Haines Annex and a second dorm each had three of these freshman rooms interspersed on hallways otherwise housing upperclassmen. Barry’s two roommates had arrived before him: Paul Carpenter had grown up in nearby Diamond Bar, California, and graduated from Ganesha High School in Pomona. Imad Husain was originally from Karachi, Pakistan, and he and his family now lived in Dubai; he had graduated from the Bedford School in England. Imad was one of many international students at Oxy; in contrast, this freshman class of 1983 included only twenty-plus African American students, mostly from heavily black neighborhoods in nearby South Central Los Angeles. Oxy’s tuition for the 1979–80 year was $4,752, with room and board adding another $2,100, for a total of just under $7,000.

Barry’s mother Ann Sutoro was earning a respectable salary from DAI in Indonesia—and, as the IRS would charge six years later, was failing to pay her U.S. taxes on it—and Madelyn Dunham still worked as a vice president at Bank of Hawaii. Decades later, an article in an Occidental publication would print Obama’s statement that he had received “a full scholarship” that he recalled totaling $7,700, and journalists would repeat that pronouncement as an unquestioned fact. But Occidental awarded financial aid only on the basis of financial need and, like Punahou, made work-study employment a part of any recipient’s financial aid package. There is no evidence in Oxy’s surviving records that support Obama’s statement about financial aid, and none of his Oxy classmates remember him working any on-campus job.

Classes began on September 20. Occidental operated on a quarter, or more accurately, trimester system—fall, winter, and spring. Most freshmen followed Oxy’s Core Program. A freshman seminar covered the basics of how to use the library and write a paper, easy indeed for anyone from Punahou. Distribution requirements mandated a sampling of American, European, and “World” culture courses across freshman and sophomore years, plus a foreign language—Spanish in Obama’s case, after his unfortunate early encounter with French at Punahou—but within that framework students had a great deal of choice. That fall Obama selected Political Science 90, American Political Ideas and Institutions, a lecture class of about 120 students taught in two five-week segments. The first, covering American political thought from Madison and Jefferson through Lincoln, the Progressives, the New Deal, and the mid-twentieth-century debate over pluralism versus elitism, was handled by Roger Boesche, a young assistant professor who had received his Ph.D. from Stanford in 1976. The second, covering the structure and powers of the federal legislative, executive, and judicial branches, was taught by Richard F. Reath, a soon-to-retire senior professor. Boesche in particular impressed Obama. One of his other enduring memories from freshman year was reading Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, published just two years earlier, in an introductory literature course.

One hope Barry brought with him to Oxy was quickly diminished, namely any future as a collegiate basketball player, even at a small Division III school. Midday pickup games at Rush Gymnasium well in advance of preseason team practice—“noon ball” in the school’s parlance—quickly demonstrated that Oxy had plenty of players with talent well beyond what Obama had seen in Hawaiian high school AA games. Barry was still not a good outside shooter, and he was so left-handed he always drove leftward and could not cross over. His love of basketball would remain, but his final official team game had taken place in Honolulu six months earlier.

Instead Obama’s freshman year revolved around Haines Annex, with its mix of students crammed into tiny rooms on a narrow hallway with one alcove that offered an old couch of uncertain color. In addition to Barry, Paul, and Imad, a second freshman triple included Phil Boerner, a graduate of Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland, whose father was a foreign service officer stationed at the U.S. embassy in London. Another triple just around the corner housed Paul Anderson from Minneapolis, a track-and-field athlete. A sophomore triple right across the hall had two Southern Californians, Ken Sulzer and John Boyer. A second next door included Sim Heninger, a North Carolina native who had grown up in Bremerton, Washington; a third had Adam Sherman, from Rockville, Maryland. Tight quarters made for open doors and quick, close friendships. One night early on Barry, Paul Carpenter, Phil Boerner, John Boyer, and others drove to Hollywood to see the movie Apocalypse Now, which had opened just a few weeks earlier. There was a long line; right in front of the Oxy crew was the well-known musician Tom Waits, who Phil remembered was “quite wasted.”

Getting wasted happened at Oxy too, and perhaps more in Haines Annex than in any other dorm. Loud music helped set the tone, and as Ken Sulzer drily recalled, “if there was an alcohol restriction in the dorms, I wasn’t aware of it.” But drinking wasn’t the half of it. “Choom” and “pakalolo” weren’t part of mainland vocabulary, but partaking was even more common in Haines Annex that 1979–80 school year than Barry’s trips up to Pumping Station had been a year earlier. Adam Sherman, who was an enthusiastic participant in what he later would acknowledge was a “very wild year,” wrote a short story describing the group of regulars who gathered at least four or five nights a week in the hallway alcove that Sim Heninger termed “a male sanctum.” The “threadbare couch” sat on a “cigarette-scarred” “aquamarine carpet which is littered with broken, stale potato chips” and “a few mangled and crushed beer cans.” Drawing from a ceramic “crimson bong,” “the dope” is passed from Paul Carpenter, whose blue eyes are “glazed over in pink, dilated inebriation,” to Imad and then to Sim Heninger. The early-morning scene ends with Paul waking Adam from a sound sleep on the hallway floor. Other nights proceeded more energetically, with Phil Boerner ruefully recalling how the regulars would “repeatedly break the fire extinguisher glass during late-night wrestling matches.”

Barry Obama was a nightly participant in the hallway gatherings. John Boyer, who kept an irregular journal over the course of the year, recorded how Adam was upset after one holiday break when Obama failed to bring something back for the group from the lush environs of Oahu. Carpenter remembered Obama as someone who “listened carefully” during hallway discussions; Michael Schwartz, a good friend of Carpenter’s and Anderson’s, remembered Barry as “reserved” and can picture him drinking beer out of a paper cup. Samuel Yaw “Kofi” Manu, a Ghanaian student who met Obama in the introductory political science class, recalls how “extremely friendly” Obama was; sophomore Mark Parsons, a fellow heavy smoker, remembers Barry telling him, “I smoke like this because I want to keep my weight down.” John Boyer still has an image of Barry and Adam having long, late-night conversations on the decrepit couch. Obama was “personable” and “quick to laugh,” with “a great sense of humor.” But Boyer notes that Barry was “always vague” about his family, and even during those late-night discussions, with beer and marijuana relaxing most everyone’s demeanors, “there was always kind of a wall” on Barry’s part. It was “not really aloofness,” Boyer explained, but something self-protective; Obama was more an observer than a spontaneous participant. “ ‘Remove’ is a good word,” Boyer concluded.

One Friday night in mid-October Barry, Sim, and a sophomore woman were sitting in Haines Hall proper, all under the influence of mood enhancers. In Barry’s case those included psychedelic mushrooms, and as a result, Obama “just came unglued. He was a mess.” Sim believed that Barry had been adopted and raised by an older white couple whose photo he once displayed, but this night, as Obama babbled about identity and nudity and not wanting to experience rejection, it seemed as if he “was pretty troubled” and was experiencing a “big crisis.” At bottom Barry seemed “uncomfortable and frightened,” as well as “hysterical and angry,” Heninger remembered. “There was no barrier between us in this moment,” but for Sim “it was difficult and uncomfortable” in the extreme. Eventually Barry “scraped himself together.” Given everything that had been consumed, Sim later mused that neither Obama nor the young woman probably remembered the experience at all, even though in Heninger’s eyes it was “a big deal. We called it a day and it blew over,” and “I never talked to him about it” again.

For Thanksgiving 1979, just like on weekends “if there was wash to be done, or refrigerators to be raided,” Barry joined Paul Carpenter at Paul’s family home about thirty miles away. Mike Ramos, in college in Washington State, remembers some holiday in late 1979 when he picked up Greg Orme in Oregon and then rendezvoused with Barry and some others at Mike’s younger sister’s apartment in Berkeley, just east of San Francisco. Oxy had an almost four-week break after fall exams ended on December 6 and before winter term classes began on January 3, 1980, so Barry probably returned to Honolulu for a good chunk of that time, when Oxy’s dorms were closed.

When winter term commenced, Obama took the second course in the political science introductory sequence, Comparative Politics, which that year was taught by the campus’s most easily recognized and outspoken young faculty member, openly gay assistant professor Lawrence Goldyn. A 1973 graduate of Reed College in Oregon who had earned his Ph.D. from Stanford just months earlier, Goldyn was an unmistakable figure on Oxy’s campus. To say that Goldyn was out “would be an understatement,” political science major Ken Sulzer recalled. Goldyn was “funny, engaging,” and wore “these really tight bright yellow pants and open-toed sandals.” Gay liberation was not part of the Comparative Politics course, but Goldyn drew “a good-sized crowd” one evening during that term when he spoke on gay activism, and a column he wrote for the student newspaper ended by declaring that “the point of liberation, sexual or otherwise, is to rewrite the rules.”

Goldyn made a huge impact on Barry Obama. Almost a quarter century later, asked about his understanding of gay issues, Obama enthusiastically said, “my favorite professor my first year in college was one of the first openly gay people that I knew … He was a terrific guy” with whom Obama developed a “friendship” beyond the classroom. Four years later, in a similar interview, Obama again brought up Goldyn. “He was the first … openly gay person of authority that I had come in contact with. And he was just a terrific guy,” displaying “comfort in his own skin,” and the “strong friendship” that “we developed helped to educate me” about gayness.

Goldyn years later would remember that Obama “was not fearful of being associated with me” in terms of “talking socially” and “learning from me” after as well as in class. Three years later, Obama wrote somewhat elusively to his first intimate girlfriend that he had thought about and considered gayness, but ultimately had decided that a same-sex relationship would be less challenging and demanding than developing one with the opposite sex. But there is no doubting that Goldyn gave eighteen-year-old Barry a vastly more positive and uplifting image of gay identity and self-confidence than he had known in Honolulu.

Gayness was not one of the subjects discussed every night in Haines Annex’s grungy alcove in early 1980. But the residents did talk about the Soviet Union’s recent invasion of Afghanistan. Then, on January 23, President Jimmy Carter in his State of the Union speech announced that he would ask Congress to register young men in preparation for possibly reinstituting a military draft to augment the U.S.’s all-volunteer forces. That news gave Oxy’s small band of politically conscious students a new issue to use to regenerate significant student activism.

Two years earlier, a trio of Oxy students—Andy Roth, Gary Chapman, and Doyle Van Fossen—had responded to a challenge posed by the well-known political activist Ralph Nader during an early 1978 campus speech. Occidental, Nader noted, had some $3 million of its endowment invested in more than a dozen corporations such as IBM, Ford, General Motors, and Bank of America that did business in South Africa, which was known for its harshly racist system of apartheid. In reaction, the undergraduate Democratic Socialist Fellowship formed a Student Coalition Against Apartheid (SCAA) to demand that Oxy divest its stock holdings in companies that continued to operate there.

SCAA quickly gathered more than eight hundred student signatures on a petition calling for divestment, but in early April 1978, Oxy president Gilman rebuffed the students’ request. A week later a protest rally of more than three hundred, including Oxy’s only African American faculty member, Mary Jane Hewitt, greeted a board of trustees’ meeting that affirmed Gilman’s refusal. Several weeks later Hewitt resigned from Oxy after she was denied promotion to a higher rank, and the trio of student leaders submitted an angry letter to Oxy’s weekly newspaper saying that in light of those two outcomes “we are forced to conclude that a racial bias permeates this institution.”

By the 1978–79 academic year, the trustees’ finance committee chairman, Harry Colmery, debated Gary Chapman, head of the newly renamed Democratic Socialist Alliance (DSA) at a campus forum, but then the board announced it had ceded investment decisions to a mutual fund, thus ostensibly rendering the entire issue moot. Oxy’s faculty responded in May 1979 by adopting a resolution condemning the board’s action, but in June the trustees again reaffirmed their refusal to divest.

In early 1980, the Los Angeles Times ran two stories about Oxy and its students that highlighted how significant increases in tuition and room and board fees would raise an undergraduate’s annual tab to $8,200 the next fall. Oxy’s student body was called “introspective” by one senior, and the reporter stated that “student life today” in Eagle Rock “seems placid, serene, contemplative.” Given that portrait, a turnout of more than five hundred students at an afternoon protest rally just a week after Carter’s nationally televised speech was a dramatic triumph for Oxy’s DSA. But a second meeting drew only 150 students, and a teach-in two weeks later attracted just sixty. As winter term ended in mid-March, a student newspaper headline signaled the short-lived movement’s demise: “Anti-Draft Activism Fades with Finals.”

Oxy’s small black student population, about seventy in 1979–80, represented a marked decline from more than 120 just three years earlier. Academic attrition was high, the student paper reported, and after Mary Jane Hewitt’s resignation, two brand-new assistant professors, one in French, the other in American Studies, represented Oxy’s entire black faculty. A young black graduate of Vassar College was a newly hired assistant dean, but by spring she had submitted her resignation before a student petition effort led Oxy to successfully request that she withdraw it. Two black male sophomores, Earl Chew and Neil Moody, petitioned to establish a chapter of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, citing “a serious social and cultural problem on campus” for minority students. Chew, a St. Louis native, had graduated from tony Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and weeks earlier had taken the lead in creating an Oxy lacrosse team. But blacks at Oxy, Chew and Moody said, suffered from “a lack of cohesiveness, a generally present personal sense of being members of an ethnic minority group which cannot engage in collective achievement.” Indeed, when Oxy’s yearbook, La Encina, scheduled its 1979–80 photo of Ujima, the African American undergraduate group, only fourteen students showed up to appear in the picture. Barry Obama was not one of them.

Haines Annex’s short hallway was home to three other black male undergraduates besides Barry, sophomores Neil Moody and Ricky Johnson and freshman Willard Hankins Jr., but Obama did not develop relationships with any of them like he did with the crew of late-night alcove regulars. Most Oxy black students, particularly those from greater Los Angeles, stuck pretty much together. “There is a certain amount of minority segregation in the dining hall and in the quad,” the student paper observed. Black students who did not follow that pattern stood out.

Judith Pinn Carlisle’s African American mother had graduated from Howard University, her white father from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. She and her two siblings all attended junior high schools in Greenwich, Connecticut, but a family financial setback during Judith’s high school years had her living in South Central Los Angeles while she attended Oxy. Shy and quiet, “I kept to myself,” she said, and as a result, “I was challenged by many people on that campus as to my black legitimacy,” notwithstanding how “I’m living at Crenshaw and Adams” in the heart of black L.A. Earl Chew was a particular antagonist, treating Judith as if she was “a sellout,” she recalled. Chew “did not like me” and the hostility “was very disturbing.”

Sophomore Eric Moore’s mother had also graduated from Howard, and Eric grew up in mostly white, upper-middle-class Boulder, Colorado. “There weren’t that many black students on campus and there weren’t that many that went outside of the black clique,” he recounted. Eric had a diverse set of friends, including a junior from Karachi, Pakistan, Hasan Chandoo, who had grown up largely in Singapore and transferred to Oxy after a freshman year at Windham College in Vermont. Also from Karachi was sophomore Wahid Hamid, who roomed with French-born sophomore Laurent Delanney. Both Hamid and Chandoo had long known Imad Husain, Barry Obama’s roommate. By the spring of 1980 Chandoo was living off-campus with Vinai Thummalapally, an Indian graduate student who along with Hasan’s cousin Ahmed Chandoo was attending California State University and whose girlfriend, Barbara Nichols-Roy, who had also grown up in India, was an Oxy junior. As Eric Moore later said, they had “our own little UN there.”

Eric remembers Obama as always having “that big beaming smile,” and says he was “always in a Hawaiian shirt and some OP shorts and flip-flops.” Indeed, he says, Barry seemed “more Hawaiian and Asian and international in his acculturation than certainly he was African American.” Obama “hadn’t had an urban African American experience at all,” and at Oxy “many of the local Los Angeles African Americans were not as receptive to the cultural diversity” on campus as Eric was. Barry was “a little isolated from that group,” and just as Judith experienced, “there was some pushback from certain individuals.”

Earl Chew was the most widely visible African American student on campus, and while some found him hostile, Hasan Chandoo considered him a “really wonderful friend.” African American freshman Kim Kimbrew, later Amiekoleh Usafi, remembers Earl as “a bright and shining person” who was “just completely committed” to black advancement. Like Eric, she viewed Barry as “a really relaxed boy from Hawaii who wore flip-flops and shorts.” Obama once asked her to “come over here and talk to me,” Kim recalled. “I don’t know if he’d ever really been around black women at that point” and in terms of pursuing women, “he seemed to keep himself away from all of that.”

Spring term began the last week of March and lasted until early June. Barry, along with Paul Carpenter, was in a third core political science course, this one on international relations and cotaught by professors Larry Caldwell and Carlos Alan Egan. Junior Susan Keselenko found Egan “a very romantic figure,” but the course itself was “really tedious.” A significant portion of it involved pairs of nine-student teams contending with each other in a multistage group paper exercise that Keselenko would remember as “very kind of mechanical.” Susan and a fellow junior, Caroline Boss, ended up in “Group Y” along with Barry; Paul Carpenter was in the opposing “Group A.” Boss, a political science major and active DSA member who as a freshman had run on the progressive slate for Oxy’s student government offices, served as the group’s informal leader. In mid-May Caroline and Susan orally presented Group Y’s six-page paper, “The MX Missile: Bigger Is Not Better.”

In the January State of the Union speech that had generated Oxy’s draft registration protests, President Carter also had proposed spending as much as $70 billion to build two hundred mobile, ten-warhead-apiece MX missiles that would be deployed all across the U.S. Southwest. Attacking Carter’s proposal as “an unnecessary, economically and environmentally devastating venture,” Group Y said that if implemented, the MX project “will destabilize the international balance, accelerate the arms race, and increase the likelihood of nuclear war”—the same themes that one group member’s father had publicly articulated exactly eighteen years earlier!

Whichever instructor gave it a C was not impressed. The paper had “a certain superficial fluency or glibness,” he wrote, but “it demonstrates a very great disregard for careful thought, little concept of how one analyzes an issue, and fails to make a persuasive argument.” Ouch. Carpenter’s Group A was hardly kinder in their critique, asserting that “Group Y’s paper as a whole lacked original analysis” and that “vital contradictions … undermined their thesis considerably.” Y then penned a rebuttal as well as their critique of Group A’s own paper, which addressed the 1978 Camp David Accords. The critique received an A even though it contained multiple obvious spelling errors, including “Palestenians,” and creation of the verb “abilitated.” Obama appears to have orally presented Group Y’s critique, for in the margin alongside their paper’s statement that “A settlement amenable to the oil producing Arab states does not insure an improved position for the U.S. in regard to oil,” one of his fellow students penned “Barry > abandon Israel will not protect U.S. oil access.”

Outside of class, regular activities from earlier in the academic year continued apace. Humorous event listings in the somewhat tardy April Fools’ issue of the student newspaper included one announcing that “Haines Annex will host a religious revival this Wednesday at 8:00. Participants will be asked to let their hair down for one night in an effort to communicate with extra-terrestrial Gods utilizing the means of herbal stimuli.” Just as at Punahou a year earlier, there was hardly anything secretive about some students’ recreational preferences.

One Saturday Barry, Eric Moore, and seniors Mark Anderson and Romeo Garcia went to a music festival in nearby Pasadena Central Park. Eric remembered that “we were culture and music hounds,” but with Oxy being an “island in the barrio” of surrounding Eagle Rock, Obama would join him on drives to South Central Los Angeles to get their hair cut. Sometimes the police pulled over Eric and Barry. “It was par for the course,” Moore explained years later.