По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

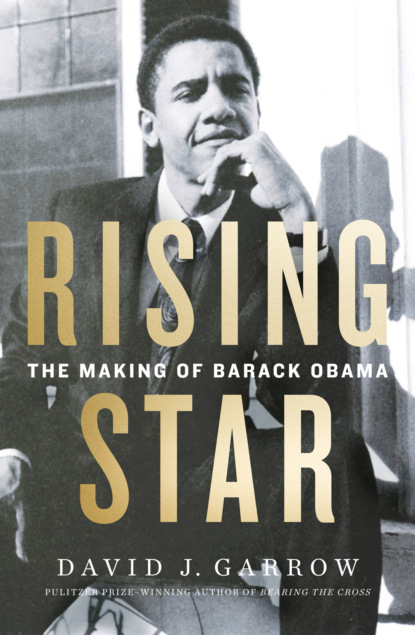

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Barry would later say that “for me, as a young boy,” Jakarta was “a magical place.” Revisiting the city more than forty years later, he recounted how “we had a mango tree out front” and “my Indonesian friends and I used to run in the fields with water buffalo and goats” while “flying kites” and “catching dragonflies.” But during the long rainy season, Jakarta was no wonderland: Barry, like others, would have to wear plastic bags over his footwear, and on one mud-sliding jaunt, he badly cut his forearm on barbed wire, a wound that required twenty stitches and left him with what he later called “an ugly scar.”

In January 1968, Ann enrolled Barry, using the surname Soetoro, in a newly built Roman Catholic school three blocks from their home—“she didn’t have the money to send me to the fancy international school where all the American kids went,” Barry later recounted. That allowed Ann to take a paid job as assistant to the director of a U.S. embassy–sponsored program offering English language classes to interested Indonesians. Barry’s school, St. Francis Assisi, as its name would be rendered in English, was avowedly Catholic: “you would start every day with a prayer,” Barry later explained, but classes met for only two and a half hours on weekday mornings. His first-grade teacher there, Israella Darmawan, decades later told credulous reporters, “He wrote an essay titled, ‘I Want to Become President’ ” during that spring of 1968, prior to his seventh birthday. She also told journalists that Barry struggled greatly to learn Indonesian; in contrast, Obama later boasted that “it had taken me less than six months to learn Indonesia’s language, its customs, and its legends.”

Barry’s second-grade teacher, Cecilia Sugini, spoke no English, but Barry received more exposure to the Indonesian language during family visits to Lolo’s relatives in Yogyakarta, in central Java. Yet even his third-grade teacher, Fermina Katarina Sinaga, later stated that eight-year-old Barry was not fluent in Indonesian. And she would also tell wide-eyed reporters that Barry, during the fall of 1969, declared in a paper, written in Indonesian, that “Someday I want to be President.” One journalist, embracing Sinaga’s direct quotation forty years later, would insist that Sinaga’s “memory is precise and there is no reason not to trust it.”

By the end of 1969, Lolo, thanks to his nephew “Sonny” Trisulo, switched to a much better job with Union Oil Company of California. Soon thereafter, he, Barry, and newly pregnant Ann moved to a far nicer home at 22 Taman Amir Hamzah Street in the better neighborhood of Matraman. Around the same time, Ann left the English teaching post, which she had come to loathe, for more rewarding work, primarily in the evenings, at a nonprofit management training school headed by a Dutch Jesuit priest.

Moving houses also meant that Barry would attend the Besuki elementary school, which traced its roots back thirty years to Indonesia’s Dutch colonial government. Classes met for five hours each weekday, double what St. Francis Assisi offered. Ann’s new work schedule gave her time to intensify her efforts to homeschool Barry in English using workbooks from the U.S. At Besuki, his all-Indonesian classmates found Barry—or “Berry,” as they pronounced it—unique not only because of his darker complexion and chubby build but also because he was the only left-hander.

Before the spring of 1970 was out, and with a second child on the way, Ann hired an openly gay twenty-four-year-old, sometimes-cross-dressing man—Turdi by day, Evie by night—to be both cook and nanny. Neighbors thought little of it. “She was a nice person and always patient and caring in keeping young Barry,” one later recalled. Turdi often accompanied Barry to and from school. Later, Turdi, at age sixty-six, told the Associated Press: “I never let him see me wearing women’s clothes. But he did see me trying on his mother’s lipstick sometimes. That used to really crack him up.”

Sometime apparently also during that spring, Barry saw something that, in his later tellings, had a vastly more powerful impact upon his young mind. A quarter century passed between the moment and Obama’s first telling of it, but in his 1995 version, the memory was of paging through a pile of Life magazines in an American library in Jakarta and finding an article with photographs of a man of color who had paid for chemical treatments in a horribly unsuccessful attempt to make himself appear white. In Obama’s 1995 account, “thousands of people like him, black men and women back in America,” had “undergone the same treatment in response to advertisements that promised happiness as a white person.” To him, “seeing that article was violent for me, an ambush attack,” leaving his image of his own skin color “permanently altered.”

In a conversation soon after writing that, Obama recounted how “after reading that story, I knew there had to be something wrong with being black.” Earlier, while “growing up in Hawaii, all of the kids were kind of brown,” so “I didn’t stand out” and “I was too busy running around being a kid” to appreciate racial differences. At his two Jakarta schools, he experienced some normal teasing by other children, but to no obvious or remembered ill effect. “He was a plump kid with big ears and very outgoing and friendly,” one of Ann’s closest Jakarta friends later recalled.

Nine years later, Obama described the memory again. “I became aware of the cesspool of stereotypes when I was eight or nine. I saw a story in Life magazine about people who were using skin bleach to make themselves white. I was really disturbed by that. Why would somebody want to do that?” A few weeks later, Obama again recounted seeing a Life magazine picture of “a black guy who had bleached his skin with these skin-lightening products.” That was “the first time I remember thinking about race” and worrying that having darker skin was “not a good thing.”

In 2007, a reporter told Obama that no issue of Life magazine ever contained such an article or such photographs; this was confirmed by Life. “It might have been an Ebony or it might have been … who knows what it was?” a flustered Obama responded. But then Ebony too examined its archive of past issues and found no such story. Indeed, the other two major picture magazines of that era, Look and the Saturday Evening Post, published no such story either. Yet Obama understandably stood by his recollection: “I remember the story was very specific about a person who had gone through it and regretted it.”

But Ebony had published a somewhat similar story, in its December 1968 issue, titled “I Wish I Were Black—Again.” It was a profile of Juana Burke, a young African American art teacher who at age sixteen had begun to suffer from vitiligo, a disease which turned portions of her dark brown skin white as it killed off pigmentation cells. The article included photographs of her forearm and legs. Dermatologists’ efforts to counteract the spread of the affliction through skin chemicals and even prolonged sunbathing failed completely, and Ms. Burke reluctantly accepted her pale new appearance.

The four-page Ebony spread stressed that she “retains her old sense of black pride and identifies with her people,” and she continued to teach at a predominantly black school. However, becoming white had left her “very pessimistic about the future of race relations in this country.” A black boyfriend had ditched her, and she was dismayed to repeatedly experience a “more courteous attitude” from white strangers than she had when she had been visibly black.

Had eight-year-old Barry actually seen that issue of Ebony? Who knows. But many teenagers growing up in the 1960s heard about a journalist named John Howard Griffin, a white Texan who, in the late 1950s, had undergone chemical treatments so he could pass as black and write about the experience—the obverse of Ms. Burke’s deflating color change. Griffin’s resulting book, Black Like Me, first published in 1961, was a nationwide best seller and was made into a major motion picture.

Irrespective of what magazine pictures young Barry did or did not see, the overarching question of how and why anyone would seek to alter their visible racial identity had become a staple of U.S. popular culture in the late 1960s, even if the notion of any African American becoming white was starkly out-of-date in the new era of “I’m Black and I’m Beautiful.” Obama’s encounter with the pictures had seemingly been a “turning point,” “a transformation in the life story that marks a considerable shift in self-understanding” and in “his racial identity development.” The Obama of 1995, 2004, and 2007–08 certainly agreed—“Growing up, I wasn’t always sure who I was”—regardless of whether at age ten, at age eighteen, or even at age twenty-seven he actually pondered the memory of those images.

Sometime in the late spring of 1970 Ann Dunham, in concert with her father and no doubt her mother, decided that within a year’s time, when Barry would begin fifth grade, he should continue his future schooling in Honolulu rather than Jakarta. Stan Dunham’s twenty-year career as a furniture salesman had ended sometime in 1968, following changes in Bob Pratt’s enterprises, and by 1969, he was one of about twenty-five agents at John S. Williamson’s John Hancock Mutual Insurance agency in downtown Honolulu. Perhaps because of a decrease in income from that shift, Stan and Madelyn had left the rental home at 2234 University Avenue and relocated to unit 1206 in the Punahou Circle Apartments at 1617 South Beretania Street, just a few blocks south of Punahou School.

Ann had been aware of Punahou, and its unequaled-in-Hawaii educational reputation, since her earliest months in Honolulu. Her son was even conceived just across Punahou Street from its spacious campus. Founded in 1841 by Christian missionaries, Punahou had a student body that was still predominantly white—haole, in local parlance—and its alumni included many of Oahu’s civic elite. Fifth grade was one of the two best opportunities—ninth was the other—for youngsters who had not started elementary school there to gain admission, as class sizes increased at the middle and then high school levels.

It is unknown when Ann first thought of sending Barry there, but Stanley had become good friends with Alec Williamson, who also worked at his father’s insurance agency. Alec’s dad had graduated from Punahou in 1937, and both of his sisters had gone there as well, although he had not. Punahou administered admissions tests and required personal interviews. It was “the quintessential local school,” Alec’s sister Susan later explained, and the Dunhams were mainlanders, but John Williamson was more than willing to recommend Stanley’s bright grandson to his alma mater: “My dad wrote the letter,” Alec recounted forty years later.

Sometime in the summer of 1970, eight-year-old Barry, apparently unaccompanied, flew back to Honolulu to live for some weeks with his grandparents—and, more important, to interview with Punahou’s admissions office and take the necessary tests. In his own later telling, those were glorious weeks—lots of ice cream and days at the beach, a radical upgrade from daily life and school in Jakarta. Then, one late July or early August afternoon, after an appointment at Punahou, and with Barry still dressed to impress, Stan took his hapa-haole—half-white—grandson to meet one of his best friends, a sixty-four-year-old black man who had fathered five hapa-haole Hawaiian children of his own.

During their first ten years in Honolulu, Stan and Madelyn’s favorite shared pastime had become contract bridge. Madelyn’s brother Charles Payne later said they played “with almost a fanaticism” and “they were really, really into it” and “worked well together.” Through that hobby, they had met another bridge-playing couple: Helen Canfield Davis, a once-wealthy white woman in her early forties, and her almost-two-decades-older African American husband, Frank Marshall Davis.

By 1970, Frank Davis’s publications, involvements, and activities—some self-cataloged, others invasively and meticulously collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1944 until 1963—were extensive enough to suggest that Davis had led three lives. And indeed he had: almost twenty years as a widely published, often-discussed African American poet and journalist, close to a decade as a dues-paying member of the Communist Party USA, and an entire adult life as an unbounded sexual adventurer.

Born the last day of 1905 in Arkansas City, Kansas—just sixty miles south of Wichita and the neighboring small towns where Stan and Madelyn Dunham would grow up some fifteen years later—Frank’s parents divorced while he was a child. He was raised by his mother, stepfather, and grandparents; he graduated from high school, spent a year working in Wichita, and then attended Kansas State Agricultural College. Already interested in poetry and journalism, he left school in 1927 to move to Chicago and found work with a succession of black newspapers there and in nearby Gary, Indiana. In 1931 Frank moved to Atlanta for a better newspaper job, and while there, he met and married Thelma Boyd. He returned to Chicago in 1934, drawn back primarily because of an intense affair with a married white woman who encouraged him to pursue poetry more seriously. His first volume of poems, Black Man’s Verse, appeared in mid-1935, followed by two more volumes in 1937 and 1938. By the early 1940s Davis had a reputation as an African American writer of significant power and great promise, a leading voice in what would be called the Chicago Black Renaissance.

Decades later, one scholar of mid-twentieth-century black literature would say that Davis was “among the best critical voices of his generation,” but his most thorough biographer would acknowledge that “Davis’s poetry did not survive the era in which it was written,” in significant part because much of it was so polemically political. Another commentator observed that “even at the moments of narratorial identification with the folk, a certain distance is formally maintained.” Similarly, asked years later about an oft-cited poem titled “Mojo Mike’s Beer Garden,” Frank readily acknowledged that his portrayal “was sort of a composite.”

Starting in 1943–44, Frank also began teaching classes on the history of jazz at Chicago’s Abraham Lincoln School, a Communist-allied institution aimed especially at African Americans. Frank would later complain that “only two black students” took the course in four years, but among the whites who enrolled was a twenty-one-year-old, newly married woman with a wealthy stepfather named Helen Canfield Peck. Within little more than a year, she and Frank had secured divorces and were married in May 1946.

In or around April 1943, Frank had become a dues-paying member of the Communist Party USA, according to FBI informants within the party. From mid-1946 until fall 1947, Frank wrote a weekly column for a newly founded, almost openly Communist newspaper, the Chicago Star; in 1948 he published 47th Street: Poems, which scholars later said was his best book of verse.

During the summer of that year, Helen Canfield Davis, who had also joined the party, read a magazine article about life in Hawaii. Not long after that, Frank spoke about the islands with Paul Robeson, the well-known singer who shared his pro-Communist views. Robeson had visited Hawaii in March 1948 on a concert tour sponsored by the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) to boost the left-wing Progressive Party. Frank also heard about life in the islands from ILWU president Harry Bridges. Then that fall, Helen received an inheritance of securities worth tens of thousands of dollars from her wealthy stepfather, investment banker Gerald W. Peck. With that windfall, Frank and Helen decided to see for themselves what Hawaii was like for an interracial couple; they packed with an eye toward making this a permanent move and arrived in Honolulu on December 8, 1948.

From their hotel in Waikiki, Frank called ILWU director Jack Hall at Bridges’s suggestion. The FBI had a tap on Hall’s phone, and this prompted them to watch Frank as well; according to Bureau files, Frank and Helen met Hall in person on December 11. Far more important, though, Frank and Helen thought Hawaii was simply “an amazing place,” and that ironically racial prejudice “was directed primarily toward male whites, known as ‘haoles.’ ” As Frank later recounted, “Virtually from the start I had a sense of human dignity. I felt that somehow I had been suddenly freed from the chains of white oppression,” and “within a week” he and Helen agreed they wanted to remain in Hawaii permanently, “although I knew it would mean giving up what prestige I had acquired back in Chicago.”

By May 1949, Frank began writing an unpaid regular column for the Honolulu Record, a weekly paper that matched his political views. In July the FBI placed his name on the Security Index, a register of the nation’s most dangerous supposed subversives, and four months on he was added to DETCOM, the political equivalent of the Bureau’s “most wanted” list of top Communists marked for immediate detention in the event of a national emergency.

Frank had realized almost immediately that he would not be able to make a living as a writer in Hawaii, and in January 1950, he started Oahu Paper Company. That same month he and Helen purchased a home in the village of Hauula, thirty miles from Honolulu in northeastern Oahu, for their quickly growing family that included daughter Lynn, who was approaching her first birthday, and son Mark, who would be born ten months later.

The FBI began constant surveillance of the Davises’ mail in mid-1950, and in March 1951, a fire at Oahu Paper destroyed thousands of dollars’ worth of stock. The Bureau’s agents reported that Frank was fully insured, and in June 1952 an informant who had quit Hawaii’s Communist Party told agents he had personally collected Frank and Helen’s monthly party dues for the last two years. In early 1953 Frank became president of the small Hawaii Civil Rights Congress (HCRC), but within two years the group was “almost inactive.” The FBI also noted that on Christmas Day 1955 the Communist Party’s national newspaper, the Daily Worker, included an article by Frank on jazz.

By that time, Frank and Helen had a third child, but in April 1956, he closed Oahu Paper, filed for personal bankruptcy, and took a job as a salesman. That summer the family moved from Hauula to Kahaluu. Several months later, Eugene Dennis, general secretary of CPUSA, writing in a national newspaper, and then Frank in his weekly Honolulu Record column, said “there is no longer a Communist Party in Hawaii.” Even so, Mississippi senator James O. Eastland, chairman of the U.S. Senate’s Internal Security Subcommittee, scheduled a December hearing in Honolulu to probe Soviet activity in the balmy islands. Fearing how Davis might dress down the notoriously racist Eastland in a public hearing, the subcommittee instead subpoenaed Davis to appear at a private executive session, where he took the Fifth Amendment three times when questioned about his CPUSA ties. Just two weeks later, in another Record column, Frank forcefully attacked the Soviet Union for its military invasion of Hungary, calling the move “a tragic mistake from which Moscow will not soon recover.”

But Honolulu FBI agents, and their informants, kept their focus on Frank. In mid-1957 he told one supposed friend that Helen had taken up with a visiting musician who was performing in Waikiki. The Bureau quickly took note of Frank’s move to the Central YMCA for a month before he and Helen reconciled and the family moved to a house up in Honolulu’s Kalihi Valley neighborhood. In February 1958 Helen gave birth to twin daughters, and a year later Frank started a new company, Paradise Papers.

Two years later, agents learned that Helen was working for Avon Products and “works mostly in the evenings making house calls. As a result, subject is now forced to spend most of his evenings babysitting and has little opportunity to contact his former friends outside working hours.” That led Honolulu agents to request that Frank be demoted from the top-risk Security Index, but FBI headquarters refused until early 1963, when it ordered Honolulu to interview Frank about his past affiliations, and Frank met with two agents in Kapiolani Park on August 26, 1963. Asked to confirm his CPUSA membership, Frank said the party had not existed in Hawaii for at least seven years and that it would do him no good to acknowledge his past membership. But, Frank added, he would “consort with the devil” in order to advance racial equality. With that the FBI finally closed its file on fifty-seven-year-old Frank Marshall Davis.

Frank busied himself with Paradise Papers, but it, and Helen’s work, hardly provided enough money to raise a family. By June 1968, Frank’s two eldest children had graduated high school, and that summer Frank earned a modest sum of money by publishing a self-proclaimed sexual autobiography, Sex Rebel: Black—Memoirs of a Gash Gourmet, under the pseudonym “Bob Greene.” It began with an introduction, supposedly authored by “Dale Gordon, Ph.D.,” which observed that the author may have “strong homosexual tendencies.” “Bob Greene” then acknowledged that “under certain circumstances I am bisexual” and stated that “all incidents I have described have been taken from actual experiences” and were not fictionalized. “Bob’s” dominant preference was threesomes, and he recounted the intense emotional trauma he experienced years earlier when he learned that a white Chicago couple with whom he had repeatedly enjoyed such experiences were killed in a violent highway accident.

“Bob,” or Frank, championed recreational sex, arguing that “this whole concept of sex-for-reproduction-only carries with it contempt for women. It implies that women were created solely to bear children.” And Frank did little to hide behind the “Bob Greene” pseudonym with close friends. Four months after the 323-page, $1.75 paperback first appeared, Frank wrote to his old Chicago friend Margaret Burroughs to let her know about the availability of “my thoroughly erotic autobiography.” Since it was “what some people call pornography (I call it erotic realism),” it would not be in Chicago bookstores. “You are ‘Flo,’ ” and “you will find out things about me sexually that you probably never suspected—but in this period of wider acceptance of sexual attitudes, I can be more frank than was possible 20 years ago.” He closed by telling Burroughs, “I’m still swinging.”

In June 1969, Frank moved from his family’s home to a small cottage just off Kuhio Avenue in the cramped, three-square-block section of Waikiki known as the Koa Cottages or simply the Jungle. He and Helen divorced the next year, and, as his son Mark would later write, Frank “entered his golden years with glee,” given what life in the Jungle offered. As Frank described it, his little studio had a tiny front porch “only two feet from the sidewalk” and “my pad is sort of a meeting area, kind of a town hall to an extent.” The Jungle was “a place known for both sex and dope,” and was really “a ghetto surrounded by high-rise buildings,” but it was without a doubt “the most interesting place I have ever lived.” Soon after moving there, Frank became known as the “Keeper of the Dolls,” and he later recounted how he had written “a series of short portraits called ‘Horizontal Cameos’ about women who make their living on their backs.”

Two of Frank’s closest acquaintances from the early and mid-1970s readily and independently confirm that Stan Dunham was one of Frank’s best friends during the years he lived in the Jungle. Dawna Weatherly-Williams, a twenty-two-year-old white woman with a black husband and an interracial son, was by 1970 effectively Frank’s adopted daughter and called him “Daddy.” She later described Stan as “a wonderful guy.” She said he and Frank “had good fun together. They knew each other quite a while before I knew them—several years. They were really good buddies. They did a lot of adventures together that they were very proud of.” As of 1970 Stan “came a couple of times a week to visit Daddy,” and the two men particularly enjoyed crafting “a lot of limericks that were slightly off-color, and they took great fun in those” and in other discussions of sex, which Dawna would avoid.

Despite what was readily available in the neighborhood, “Frank never really did drugs, though he and Stan would smoke pot together,” Dawna remembered. Stan had told Frank about his exceptionally bright interracial grandson well before August 1970. According to Dawna, “Stan had been promising to bring Barry by because we all had that in common—Frank’s kids were half-white, Stan’s grandson was half-black, and my son was half-black.” Decades later she could still picture the afternoon when Stan brought young Barry along to first meet Frank: “Hey, Stan! Oh, is this him?” She remembers that over the next nine or ten years, Stan brought his grandson with him again and again when he went to visit Frank, and as Barry got older, Stan encouraged him to talk with Davis on his own. Obama would remember, “I was intrigued by old Frank,” and years later his younger half sister, Maya Kassandra Soetoro, who was born on August 15, 1970, during her brother’s visit with their grandparents in Hawaii, described Stanley telling her that Davis “was a point of connection, a bridge if you will, to the larger African American experience for my brother.” Once Obama entered politics, Davis’s Communist background plus his kinky exploits made him politically radioactive, and Obama would grudgingly admit only to having visited Davis maybe “ten to fifteen times.”

Soon after Ann Dunham Soetoro’s second child was born, Madelyn Dunham, along with her grandson, flew to Jakarta to see her new granddaughter and to meet Lolo’s mother and family. Within weeks nine-year-old Barry was back at Besuki school to start fourth grade. The boy who sat next to him, Widiyanto Hendro, later “said Obama sometimes struggled to make himself understood in Indonesian and at times used hand signals to communicate.” The summer in Honolulu had not improved his limited grasp of the Indonesian language, and Lolo’s relatives who saw Barry during his fourth-grade school year noted how much chubbier he had become during his now three-plus years in Indonesia.

For more than a year in Honolulu, Lolo Soetoro had served as Barry’s off-site stepfather, often roughhousing with him and also playing chess with Stanley at the Dunhams’ home. Then, in Jakarta, Barry lived with Lolo on a daily basis for just more than three years, and throughout that time the young boy was impressed with Lolo’s knowledge and self-control, especially the latter. “His knowledge of the world seemed inexhaustible,” particularly with “elusive things,” such as “managing the emotions I felt,” Obama would later write. Lolo’s own temperament was “imperturbable,” and Barry “never heard him talk about what he was feeling. I had never seen him really angry or sad. He seemed to inhabit a world of hard surfaces and well-defined thoughts.”

Three decades later, after Obama’s memoir Dreams From My Father was published, he would select the brief portrait of Lolo he had written when asked to give a short reading from his book. In that scene, young Barry asks his stepfather if he has ever seen someone killed, and when Lolo reluctantly says yes, Barry asks why. “Because he was weak,” Lolo answers. Barry was puzzled. Strong men “take advantage of weakness in other men,” Lolo responds, and asks Barry, “Which would you rather be?” Lolo declares, “Better to be strong. If you can’t be strong, be clever and make peace with someone who’s strong. But always better to be strong yourself. Always.”

In subsequent years, Obama would believe that by 1970–71, Lolo’s acclimation to his new job with Union Oil led Ann to become increasingly disillusioned with her second husband’s evolution into an American-style business executive. Obama admired Lolo’s “natural reserve” if not his “remoteness,” and believed his mother’s growing disappointment with Lolo led her to use an image of his absent father to persuade her son to pursue a life of idealism over comfort. “She paints him as this Nelson Mandela/Harry Belafonte figure, which turns out to be a wonderful thing for me in the sense that I end up having a very positive image” of my father, Obama would later recount. “I had a whole mythology about who he was,” a “mythology that my mother fed me.” But his memories of Lolo from 1970–71 would become dismissive. “His big thing was Johnnie Walker Black, Andy Williams records,” Obama recalled. “I still remember ‘Moon River.’ He’d be playing it, sipping, and playing tennis at the country club. That was his whole thing. I think their expectations diverged fairly rapidly” after 1970.

Some scholars would later credit “the Javanese art of restraint, of not displaying emotions, of never raising your voice,” all of which young Barry witnessed in Lolo, with deeply influencing Obama. Lolo “was as close to a father figure as Obama ever had,” albeit briefly, and “the lessons Obama learned from Jakarta and Lolo,” particularly not “disclosing too much about how one feels,” supplied the human template for Obama’s own practice and appreciation of the “benefit of managing emotions,” a second commentator would conclude.

In subsequent years, when asked about the impact on him of his three-plus years in Indonesia, Obama more often cited an external perception—“I lived in a country where I saw extreme poverty at a very early age”—than any internal conclusions or emotional lessons. “It left a very strong mark on me living there because you got a real sense of just how poor folks can get,” he told one questioner twenty years later. “I was educated in the potential oppressiveness of power and the inequality of wealth,” he told another. “I witnessed firsthand the huge gulf between rich and poor” and “I think it had a tremendous impact on me,” he explained more than once. Such an insistent theme would lead one smart journalist to assert years later that for Obama, “Indonesia was the formative experience.”

Sometime soon after his tenth birthday, in early August 1971, Barry again flew from Jakarta to Honolulu. As he had the previous summer, he would live with his grandparents, and in September he began fifth-grade classes at Punahou School, just a four-block walk up Punahou Street. Families of fifth (and sixth) graders received a “narrative conference report form three times during the school year. No letter grades are given. At the initial conference during the fall, achievement test scores, the class standing and a detailed written evaluation of progress in each subject area will be discussed.” Four major subject areas—Language Arts, Social Studies, Mathematics, and Science—were supplemented by a weekly arts class, a music class, and four sessions of physical education. A year’s tuition was $1,165. With two well-employed parents, plus his grandparents—Madelyn nine months earlier had been named one of Bank of Hawaii’s first two women vice presidents—Obama did not receive any form of financial aid.

For Mathematics and Science, Barry was taught by twenty-five-year-old Hastings Judd Kauwela “Pal” Eldredge, who had graduated from Punahou seven years earlier and earned his undergraduate degree at Brigham Young University. For Language Arts and Social Studies, in 307 Castle Hall, Barry had his homeroom teacher, fifty-six-year-old Mrs. Mabel Hefty, a 1935 graduate of San Francisco State College who had taught at Punahou since 1947 and had spent a recent sabbatical year teaching in Kenya. At Punahou, fifth graders had homework, and after a brief period of Barry tackling it at the Dunhams’ dining room table, Stan asked Alec Williamson, his insurance agency friend, to build a desk to go in Barry’s small bedroom. In return, Barry offered Williamson a guitar he had lost interest in. (Williamson still had it more than forty years later.)

As an adult, Obama would praise Hefty for making him feel entirely welcome and fully at home among classmates, most of whom had been together since kindergarten or first grade. Hefty split her class into groups of four at shared desks; Barry was with Ronald Loui, Malcolm Waugh, and Mark “Hebs” Hebing, his best friend that year. “Mrs. Hefty was a great teacher,” Hebing recalled. “One of the first things we had to do” was “memorize the Gettysburg Address”—“the whole thing.” In Hebing’s memory forty years later, Barry was the first student to succeed.

There was one other African American student, Joella Edwards, in Barry’s fifth-grade class, and she was “shocked” by the arrival of her new classmate. She would remember Barry as “soft-spoken, quiet, and reserved,” but he hung back from befriending her in any way. Ronald Loui, like Joella, would recall other classmates teasing both her and Barry with common grade-school rhymes. “There were many times that I looked to Barry for a word, a sign, or signal that we were in this together,” Joella later wrote, but none ever came. For the next three years too—grades six, seven, and eight—they would be the only two black students in Punahou’s middle school, but no bond ever formed before Joella left Punahou come tenth grade.

In late October 1971, Ann Dunham returned to Honolulu from Jakarta. It is unclear who suggested what to whom, but the timing of her trip was not happenstance because five weeks or so after her arrival in Honolulu, Barack H. Obama Sr. arrived there as well, from Nairobi.

The seven years since Obama Sr. had been forced to leave the United States in July 1964 had been eventful and often painful. Not even a week after his departure, an agitated woman from Newton, Massachusetts, Ida Baker, twice telephoned the Boston INS office to report that her twenty-seven-year-old daughter, Ruth, was so romantically infatuated with Obama she was planning to follow him to Kenya and get married. In late August, Mrs. Baker called again to say that Ruth had flown to Nairobi on August 16. An INS agent checked in with Unitarian reverend Dana Klotzle, as well as an official at Harvard, both of whom reported that Obama already had two wives, plus a child in Honolulu. Mrs. Baker acknowledged that Ruth knew of at least the wife in Kenya, but pursued Obama anyway. The agent concluded the report with: “Suggest we discourage her from further inquiries,” because it was “time consuming and to no point where her daughter, an adult and apparently fully competent, is in possession of the information re Obama’s marriages.”

Ruth Beatrice Baker, a 1958 graduate of Simmons College, had become involved with Obama in April 1964 after meeting him at a party. “He had a flat in Cambridge with some other African students, and I was there almost every day from then on. I felt I loved him very much—he was very charming and there never was a dull moment—but he was not faithful to me, although he told me he loved me too.” In June, Obama told her he had to return to Kenya, but said she “should come there, and if I liked the country we could marry. I took him at his word” and bought a one-way plane ticket despite how “devastated” her parents were. But Obama was not at the Nairobi airport to meet her, and a helpful airport employee who knew Obama took her home, made some phone calls, and Obama soon appeared. “We went off and started living together” in a home at 16 Rosslyn Close, but “right from the very start he was drinking heavily, staying out to all hours of the night” and “sometimes hitting me and often verbally insulting me,” Ruth later recounted. “But I was in love and very, very insecure so somehow I hung on.”