По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

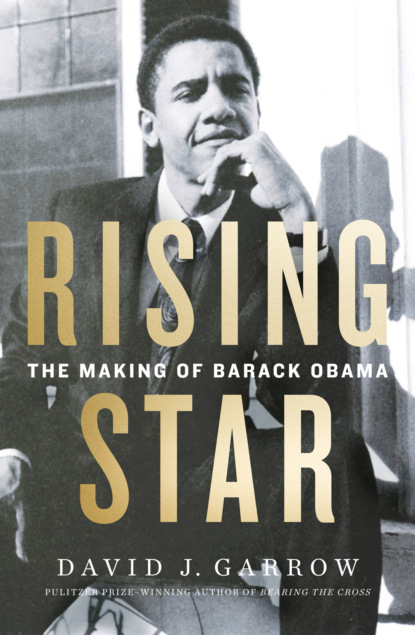

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At first only one little-known housing policy expert, Calvin Bradford, was determined to unmask a widely ignored evil. The term “redlining” was well known, if not well understood, but in newly African American neighborhoods like Roseland, it was not lenders’ refusal to make conventional home mortgage loans available to black home buyers that wreaked widespread damage, but how the FHA, starting in August 1968, made government-insured loans available to such purchasers—often through exploitative mortgage bankers, and even for properties of dubious quality—that ended up decimating newly black neighborhoods in which such insured loans were concentrated.

Bradford and a coauthor figured out that while seeking to “encourage inner-city lending,” the FHA caused local mortgage bankers to simply maximize the number of black purchasers they could entice to buy homes. As a result, thousands of black families were issued mortgages that they were not qualified to successfully carry—especially in an urban economy where blue-collar jobs like those at the Southeast Side’s steel mills were vanishing by the thousands year after year. The result was “massive numbers of foreclosed and abandoned properties,” with the FHA insurance actively encouraging fast-buck lenders to foreclose as quickly as possible on as many properties as they could.

As Bradford explained in a subsequent essay, the federally insured loans provided “the certainty that FHA will take the property from the lender after foreclosure and pay the claim,” and that led to lax underwriting and the profligate issuance of loans because “neither the mortgage companies that originated them nor the investor that purchased them—basically FNMA [popularly known as Fannie Mae, the Federal National Mortgage Association] cared about the soundness of the loans.” Indeed, as Bradford later observed, “the financial incentives were so great that scores of real estate agents, lenders, and even FHA officials engaged in fraud in order to make sales to unqualified and unsuspecting minority homebuyers.” The end result, as dramatically witnessed in Roseland, was “the government taking all of the losses and the communities suffering all the devastation” of foreclosed and abandoned homes.

The impact of such policies and such behavior could be seen all across Roseland, both in “board-ups”—homes with plywood covering their windows—and in the rapid decline of the South Michigan Avenue shopping district. One group, the Greater Roseland Organization (GRO), founded in 1969, tried to ease the racial transition. The GRO was comprised of smaller, neighborhood-specific groups such as the Pullman Civic Organization and the Roseland Heights Community Association, and it included both older white residents, like Holy Rosary’s Ralph Viall, and newly arrived African Americans, like Mary Bates and Lenora Rodgers. With funding support from both CHD and the Chicago Community Trust, GRO emerged in the early 1980s as the only audible voice speaking for the neighborhood.

The summer of 1980 saw the first stirrings of gang influence in Roseland, and in September the long-famous Gatelys Peoples Store, the largest business on South Michigan Avenue, closed. A citywide study of different neighborhoods’ needs described Gatelys’ closure as “psychologically … probably the most serious blow imaginable” to Roseland’s economic well-being. Then early in 1981, in three separate incidents, three teenage students at Fenger High School were shot and killed. By this time, close to five hundred properties in Roseland and West Pullman were in foreclosure, and more than sixteen thousand people, one-quarter of Roseland’s population, were receiving public aid. A study of recent job losses in the area highlighted Wisconsin’s closing and stated, “Many of these workers were Roseland residents.” Their prospects for new steel plant jobs were nonexistent, the report underscored: “People in these types of jobs are not merely out of work, they are out of careers.”

A parallel study, focusing on men who had lost their jobs at U.S. Steel’s South Works, found that 47 percent had not found new employment, but that summary statistic concealed a significant racial disparity: 67 percent of black workers were still unemployed, as compared to only 32 percent of whites. “Once laid off from their mill jobs,” the study noted, “blacks in particular remain the least likely to find new jobs.”

In early 1983, Lenora Rodgers mounted a renewed push to win foundation funding for GRO. She told one foundation that “community organizing and an issue-based community organization is the key to neighborhood preservation.” She said GRO’s greatest need was to hire organizers, since “organizers help to identify new and potential leaders” who could mobilize Roseland against the dangers engulfing it. But Rodgers’s efforts were unsuccessful, and by April 1984 GRO was no longer responding to letters from potential funders.

As Jerry Kellman extended CCRC’s presence into Roseland early in 1984, he accepted office space at Bill Stenzel’s Holy Rosary Parish in lieu of dues. IACT and UNO continued their antidumping protests, with Lena’s name appearing in Chicago newspapers almost weekly. On January 30, 1984, a city council committee, spurred by Alderman Vrdolyak’s desire to at least appear to be against dumping, approved a one-year moratorium on new landfills within the city. In mid-February Lena joined U.S. Representative Paul Simon, a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate seat held by Republican Chuck Percy, as he toured South Deering and its neighboring waste sites. Two days later, when the full city council approved the one-year moratorium, Vrdolyak amended the measure to exempt liquid waste handlers and transfer stations, leading Mayor Washington’s backers to oppose the diluted ban.

March 1984 was the fourth anniversary of Wisconsin Steel’s shutdown. Mayor Washington spoke at an SOJC anniversary rally, and on March 28, Frank Lumpkin and others picketed International Harvester’s downtown headquarters. Frank told one reporter he believed four hundred of the three thousand ex-Wisconsin steelworkers had died in the last four years. Later he told a U.S. congressional subcommittee that nowadays in South Chicago “the only ambition a kid can have is to steal hubcaps. There is nothing else there. There’s no jobs.” The Daily Calumet reported on the closings of more and more retail businesses; a UNO meeting on jobs drew more than five hundred neighborhood residents plus Mayor Washington’s top three development and employment aides.

By August 1984, Jerry Kellman was ready to publicly launch the reborn CCRC. Thanks to Leo Mahon’s core parishioners from St. Victor—Fred Simari, Jan Poledziewski, Gloria Boyda, and Christine Gervais—CCRC was ready to play an active role in a retraining program for one thousand former heavy industry workers in several south suburban Cook County townships, funded with $500,000 from the U.S. Department of Labor under the 1982 Job Training Partnership Act. And thanks to Bill Stenzel’s hosting of Kellman at Holy Rosary church in Roseland, Kellman was beginning to pull together a new network of virtually all-black Catholic parishes across Roseland under the distinct rubric of the Developing Communities Project (DCP), with DCP for the moment a “project” or “subgroup” of CCRC.

Kellman asked each parish for two lead representatives. From Holy Rosary came Stenzel’s two most active parishioners, Ralph Viall and Betty Garrett. At St. Catherine of Genoa, Father Paul Burak suggested two people he felt had “a passion I think for social justice”: Dan Lee, who had attended deaconate school, and Cathy Askew, a young white single parent with two mixed-race daughters who was teaching at St. Catherine’s School. St. Catherine’s senior deacon, Tommy West, was interested too, but he channeled much of his community work through another parish well north of 95th Street, St. Sabina. At St. Helena, Father Tom Kaminski volunteered himself and Eva Sturgies, an active parishioner who lived on 99th Street. From St. John de la Salle at 102nd and South Vernon Avenue, eleven blocks north of Holy Rosary, Father Joe Bennett asked Adrienne Bitoy Jackson, a young woman with an office job at Inland Steel, and Marlene Dillard, who lived in the London Towne Homes cooperative development east of Cottage Grove Avenue. Not every Roseland pastor responded with enthusiasm. At Holy Name of Mary Parish, Father Tony Vader brushed off Kellman but told his associate pastor, Father John Calicott, the only African American priest on the Far South Side, to do what he could.

The most unusual Catholic parish Kellman contacted was Our Lady of the Gardens, a church that traced its beginnings only to 1947 and which was staffed by fathers from the Society of the Divine Word. When Kellman visited Father Stanley Farier, the priest recommended two women of different circumstances: Loretta Augustine, in her early forties, who lived in a single-family home in the Golden Gate neighborhood west of the church, and Yvonne Lloyd, a fifty-five-year-old mother of eleven who lived in the Eden Green town house and apartment development just west of both Golden Gate and the sprawling public housing project from which the parish drew its name: Altgeld Gardens.

Altgeld Gardens was a by-product of World War II. When Chicago faced a dire housing shortage during the war years, officials looked to the land south of 130th Street, west of the CID landfill and Beaubien Woods Forest Preserve, north of the Cal-Sag Channel (a man-made tributary dug during the 1910s) and east of St. Lawrence Avenue. This area had in earlier decades served as the sewage farm for George Pullman’s eponymous town a mile northward. The Metropolitan Sanitary District’s massive sewage treatment plant, opened in 1922, was located just north of 130th Street. Construction began in 1943 on a 1,463-unit “war housing development” on the 157-acre site. The first families moved in come fall 1944, and a year later, in August 1945, a formal dedication ceremony featuring local congressman William A. Rowan plus Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) chairman Robert R. Taylor, an African American, took place before a crowd of five thousand. More than seven thousand residents were already living there, the Tribune reported, “nearly all Negroes.” An elementary school and then a high school, both named for the black scientist George Washington Carver, who had died in 1943, were soon part of the new development, but by 1951 school parents were protesting the presence of an open ditch carrying raw sewage that abutted the school grounds. In 1954 another five hundred apartments, officially called the Philip Murray Homes, were added to the Altgeld development.

For its first fifteen to twenty years, residents described Altgeld—or, more colloquially, just “the Gardens”—as “this heavenly place,” “just paradise,” as two different residents recalled. “It was just really a wholesome place to live,” a third remembered. “There was a feeling of family throughout the entire development,” said a fourth. The Gardens was its own world: almost anyone who worked had to own an automobile because public bus service to and from Altgeld was poor at best. “We felt so isolated and away from the mainstream of what was occurring in Chicago…. We were cut off from a lot of opportunities,” one resident explained.

Loretta Freeman Augustine grew up in Lilydale, married a man from Altgeld at age nineteen, and lived in an apartment there from 1961 to 1966, when the couple moved to a single-family home in Golden Gate, just to the west. “The community had a stability” during those years. “People had nice lawns with beautiful flowers,” and it was “very much a family-oriented community.” The Carver High School basketball team, under Coach Larry Hawkins, won the Illinois state championship in 1963.

By the late 1960s, things had changed for the worse. Many blamed the CHA, which had evicted residents when their incomes rose above the ceiling allowable in public housing. “People were being forced out because they were over the income,” one woman recalled. Dr. Alma Jones, hired as Carver Elementary School’s principal in 1975, had had a similar experience some years earlier at the CHA’s LeClaire Courts. “It was absolutely beautiful,” but “my husband got a raise, and they put us out: excess income,” she recalled. “I was devastated because I had just had twins … it was heartbreaking.” It was also destructive. “That eliminated everybody who was upwardly mobile, because if you … started to progress, then they put you out, which was the worst thing that could possibly happen” because “you take out the element of folk who know how to live in a community.”

One young man who grew up in Altgeld in the 1950s returned to the Far South Side twenty-five years later as a police officer. Initially “there were very few troubled families. I would say less than 5 percent. When I returned, I saw that the 5 percent was still residing in that development, but so were their children, and grandchildren, it was just a procession. The 5 percent had expanded to 85 percent.” Another resident said, “It began to change in the 1970s. I don’t think it really started to decline until the drugs became prevalent.” A 1972 Tribune article marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of Our Lady of the Gardens parish described Altgeld as a place “from which long-time residents are striving to get out” and stated that drugs and crime were the Gardens’ top problems. As Father Al Zimmerman commented, “With no job prospects, the temptation to turn to drugs is powerful.”

In April 1974 Altgeld made news in a different fashion when the entire facility was evacuated after a tank containing 500,000 gallons of silicon tetrachloride ruptured at a tank farm just ten blocks to the north. “A dense cloud of fumes half a mile wide” drifted toward the project, and almost twelve hours passed before residents were allowed to return home. More than two hundred people were hospitalized from exposure to “a heavy cloud of hydrochloric acid” that was generated when clueless workers turned firehoses on the tank, making the emissions far worse, rather than notify public officials. Chicago soon filed suit against Bulk Terminals, the tank’s owner, and the Tribune quoted a state official as saying, “It should be a criminal offense to know of a leakage of toxic materials without reporting it immediately.”

A 1982 citywide neighborhoods study found that Altgeld’s needs were especially dire. “The physical isolation of this community from the rest of the city” was so great that “residents of this area are rural rather than urban poor,” it noted. Tenants believe “that job training is one of their community’s most important needs,” but people who had never held a job needed to be taught “how to look for work.” Yet “many do not own cars,” and public transport was still “frightfully poor.” The Gardens’ one small food store shocked the outsiders. Not only did it smell “particularly bad,” but rats were now regularly “visible in the food store during daylight hours.” That study pointedly advised that “Altgeld Gardens needs an advocate and/or organizer to improve the coordination of the many municipal services provided to the development, and to work with the private sector to help create employment opportunities for local residents.”

Altgeld residents were theoretically represented by a local advisory council, but by the early 1980s, the council had for years been dominated with an iron fist by its president, Esther Wheeler, or “Queen Esther” to many dismayed residents. “Her whole concern was nobody would take her place, or usurp her authority,” Carver principal Alma Jones later explained. “She was extremely authoritarian and she owned Altgeld.” But come September 1982, residents had a new opportunity to organize against the toxic waste, garbage, and sewage that surrounded them, when Hazel Johnson, a forty-seven-year-old widow and mother of seven who had first moved to the Gardens in March 1962, founded People for Community Recovery (PCR) and attracted a small band of active members.

Hazel’s husband John had died of lung cancer in 1969, at age forty-one, and by the early 1980s, questions arose about the long-term health of those living at Altgeld. In late April 1984, Hazel saw a television news story about a study of cancer rates in the Far South Side. Its statistics were alarming, yet Illinois EPA director Richard Carlson brushed aside the findings. In response, Hazel contacted the IEPA, which tried to placate her with some pollution complaint forms. She responded by distributing several hundred of them throughout the Gardens over the ensuing six months.

In late 1983, a new organizing effort began in the Eden Green community. Madeline Talbott and Keith Kelleher, two Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN) organizers, had met Tom Joyce while working in Detroit, and Tom’s Claretian Social Development Fund provided the initial seed money to launch ACORN in Chicago. ACORN’s Eden Green organizer was Grant Williams, who had worked for ACORN in Philadelphia and St. Louis. Williams viewed Eden Green as more promising turf than Altgeld, but after a founding meeting of South Side United Neighbors, Williams expanded his work into the Gardens. He contacted Lena and her IACT colleagues about the new-dumps moratorium, but in Altgeld, the residents’ biggest concern was the poor public bus service to the outside world. By March 1984 Williams had interested a reporter from Chicago’s premier African American newspaper, the Defender, in Altgeld’s transit plight, and a community meeting to oppose possible service cuts by the Chicago Transit Authority drew a good crowd.

By summer, Williams had signed up some eighty-three dues-paying members for ACORN—$16 a year—but by late August, he was moving to Detroit, and a brand-new University of Chicago graduate, Steuart Pittman, would take over in September.

Before the end of summer 1984, Jerry Kellman also made his first successful forays toward enlisting some Protestant pastors to join his previously all-Catholic CCRC. His first two recruits were Rev. Bob Klonowski of Hegewisch’s Lebanon Lutheran Church and Rev. Tom Knutson of First Lutheran Church in Harvey, a far-from-prosperous suburban town two miles southwest of Altgeld Gardens. Also joining CCRC was St. Anne Parish in suburban Hazel Crest, whose new pastor, Father Len Dubi, had known Kellman for more than a decade. The city parishes’ DCP designees first met Kellman and their CCRC colleagues from St. Victor and the other predominantly white congregations at Tom Knutson’s church in Harvey.

An early August issue of the Daily Calumet ran a prominent story heralding CCRC’s “phoenix-like return.” It quoted Kellman as saying he hoped sixty churches would join by October, and that by year’s end he wanted to have “a full range of support programs for laid off workers.” His top goal was to devise “a long-range plan for economic development,” and within a year he hoped to have “three or four full time employees.” Fred Simari and Gloria Boyda from St. Victor were appointed to a task force overseeing the new federally funded suburban job retraining program, but the program would not be able to accept applications until December or January.

Throughout the fall of 1984 and early 1985, IACT, Hazel Johnson’s PCR, and even ACORN appeared more visibly active than CCRC and DCP. A mid-September appearance by IEPA director Richard Carlson at St. Kevin drew an angry crowd that erupted in shouting when he insisted that the Southeast Side’s bevy of waste facilities posed no threat to anyone’s health. Marian Byrnes from Jeffery Manor, a widowed, recently retired schoolteacher who had founded the Committee to Protect the Prairie to avert construction on the undisturbed, 117-acre Van Vlissingen Prairie north of 103rd Street, forcefully told Carlson, “We will never believe you! You might as well go home!” That tussle was quickly overshadowed when the Chicago Sun-Times reported that water from at least three residential wells just south of Altgeld Gardens contained cyanide, benzene, and toluene. Most Chicago residents were no doubt surprised that anyone within the city limits had to rely upon wells for water service, but city officials had been aware of the issue for three months. Homeowners in the tiny, seven-home enclave called Maryland Manor paid city taxes but had neither paved streets nor water and sewer service. The residents were wary enough of their cloudy well water that they used it only for toilets and the like, as opposed to drinking, but the extensive press coverage was a huge embarrassment for Mayor Washington, one that would have been worse had the press known that the issue had been handed off to an intern over the summer.

In late October, just two weeks before the November general election, Lena and her colleagues successfully targeted incumbent U.S. senator Chuck Percy after he skipped a UNO candidates’ forum with Democratic challenger Paul Simon. UNO followed Percy to a black radio station, WVON, and stormed the building, causing the beleaguered senator to take refuge in a women’s restroom. Percy remained locked inside there for some hours, and the standoff made for memorable local television news footage. On November 6, Simon defeated Percy by fewer than ninety thousand votes out of more than 4.6 million that were cast.

When the U.S. EPA denied an IACT request to review the state’s finding of no health threat, Lena told the media the refusal was “quite ironic” in light of the Maryland Manor contamination. In mid-November, when state officials authorized the cleanup of an abandoned dump at 119th Street that contained 1,750 barrels of unknown chemical waste, Governor Thompson showed up wearing a protective suit, boots, and a mask to tell journalists that the site was “a monument to man’s greed and disregard for the health and safety of fellow citizens.” Along with Frank Lumpkin’s SOJC, UNO also continued to push city officials to open a job retraining center on the Southeast Side, but environmental issues had now replaced economic ones at the top of the local agenda.

ACORN’s fall 1984 efforts in Altgeld Gardens underscored that shift. Once Steuart Pittman took over from Grant Williams, the small group changed its name to Altgeld Tenants United (ATU). Williams had warned Pittman that local advisory council (LAC) president Esther Wheeler was “kind of nuts,” but when ATU sought to use the project’s community building for a neighborhood-wide meeting, Wheeler summoned “your Leader” to meet with her executive board. ATU still drew more than one hundred residents to an October 30 meeting, but Wheeler showed up to accuse Pittman of having an intimate relationship with an elderly and devout ATU leader: “That white boy is shacking up with Maggie Davis.” It was a ludicrous allegation, but Wheeler’s role in Altgeld caused untold harm to the Garden’s residents. As Pittman reported to ACORN’s Madeline Talbott, “the grocery store”—the one whose visible population of daytime rats had astonished outsiders several years earlier—“has a plaque award for community service in it from Esther Wheeler and the LAC.”

ATU reached out to both the city’s sewer department and to CHA’s Altgeld head manager, Walter Williams, who told the organization, “I’ll resign my job before giving in to tenants’ demands.” The sewer department deployed workers, who told residents Altgeld’s sewers were the worst they had ever seen and would take months to clean, but work was halted after one week by the CHA, which would have to foot the bill. In response, over a dozen ATU members picketed CHA headquarters in the downtown Loop on November 14 and then held a press conference.

The African American Defender gave them front-page coverage, and the local 9th Ward alderman, Perry Hutchinson, took an interest, telling the Defender that “Chicago has forgotten about south of 130th Street” and the people marooned there. But Pittman was disappointed that turnout at ATU meetings was declining. When he arranged a January 23 tour of WMI’s huge CID landfill east of Altgeld, only ten people showed up. Hoping to spur greater interest, he adopted Lena and IACT’s tactic from almost two years earlier, and on February 19 sixteen ATU protesters blocked garbage trucks’ entry into the landfill. Pittman, the elderly Ms. Davis, and one young man were arrested. For a second blockade on March 7, only eight people participated, and the protest resulted in three more arrests. Pittman had privately given ACORN notice four months earlier that he would be leaving as of March 15, 1985, and when he departed no one immediately replaced him. At their final meeting, ATU members wondered whether they should join Hazel Johnson’s PCR.

In mid-January 1985, PCR received attention citywide for the first time when Hazel held a press conference to publicize the IEPA complaint forms she had circulated within Altgeld over the previous six months and to highlight that the city’s one-year moratorium on new landfills would expire on February 1. One week later, Mayor Washington called a City Hall press conference, and with both Lena and Hazel standing behind him, recommended a six-month extension of the ban, which was unanimously approved by the city council. Washington also appointed a Solid Waste Management Task Force to study the city’s landfill options. Lena, Hazel, and Bob Ginsburg from Citizens for a Better Environment were all named to the panel, as were 9th and 10th Ward aldermen Hutchinson and Vrdolyak and South Chicago Savings Bank president James A. Fitch; Washington administration insiders like Jacky Grimshaw and Marilyn Katz were also included to assure that the task force would not go astray.

By early spring 1985, however, rumors had gradually spread that the city administration was quietly considering an entirely different new landfill possibility, centered on 140 acres of Metropolitan Sanitary District property south of 130th Street on the east bank of the Calumet River, a location generally spoken of as the O’Brien Locks site after a nearby dam. A city Planning Department draft report had discussed the idea a year earlier, and while Mayor Washington reiterated his opposition to any dump at the 116th Street Big Marsh location when he spoke at UNO’s annual convention at St. Kevin in late April, concerned residents of Hegewisch and its northern Avalon Trails neighborhood—both just east of the O’Brien property—publicly criticized Lena and UNO for not pressing Washington for a similar commitment concerning the O’Brien site.

The weekly Hegewisch News began to sound the alarm, with editor Violet Czachorski proclaiming that while Hegewisch residents had supported people in South Deering in opposing any Big Marsh landfill, now UNO and IACT were failing to take a similarly principled stance when a landfill was proposed for Hegewisch’s backyard rather than theirs. Writing in the News, University of Illinois at Chicago geographer James Landing, who in 1980 had created the Lake Calumet Study Committee to help protect that body, warned that a “lack of unity among neighborhood groups … serves the interests of the dump companies.”

Harold Washington and his top aides were devoting attention to Roseland as his four-year term approached its halfway mark. In part their concern was stimulated by the Borg-Warner Foundation, whose executive director, Ellen Benjamin, had taken an interest in the neighborhood and had commissioned a “needs assessment” from a team at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Roseland had lost more than sixty-eight hundred jobs between 1977 and 1983, and loss of employment meant “many people are having trouble maintaining their houses, keeping food on the table” and avoiding foreclosure. The researchers conducted 115 interviews in Roseland, and while 33 respondents named jobs as the top problem, almost twice as many—64—described how “crime and gangs have proliferated and the feeling of insecurity has increased.” Before the report was issued, Washington’s top staffers were briefed on the findings. “Highest infant mortality rate in city,” “highest number of foreclosed homes in the nation,” South “Michigan [Ave.] business district gone,” their notes recorded. With just one exception, community groups were disappointing: “Good Roseland Christian Ministries,” the staff notes emphasized.

At 1:30 P.M. on Sunday, March 17, a man wearing a long dark coat and a baseball cap with the Playboy logo drew a gun on cashier Lavergne McDonald inside Fortenberry Liquors at 36 East 111th Street in central Roseland. She screamed, and the gunman fled. Fifteen minutes later, Roger Nelson, a seminary student who had interned at Roseland Christian Ministries, his fiancée, and his parents finished chatting with Tony and Donna Van Zanten after church services and crossed South Michigan Avenue just north of 109th Street to the lot where their car was parked. The same gunman came up to them, ordered them into the car, and instructed them to hand over their valuables. Roger’s father, fifty-year-old Northwestern College of Iowa professor Ronald Nelson, was in the driver’s seat, with the gunman crouched by the open driver’s door. As the quartet fumbled through their belongings, Donna Van Zanten and her son Kent approached and were also ordered into the back seat. Ronald Nelson handed the man his car keys and checkbook, but the gunman angrily said, “I don’t think you gave me all you have.” Nelson protested, but the gunman handed back the checkbook, called Nelson a “Goddamned lying bastard,” and fired one shot into the left side of Nelson’s abdomen.

As Ronald Nelson lay dying at the scene, the gunman fled past two men working on a car nearby. “Brothers, you all be cool,” the gunman called out. “You know them was honkies over there.” One of the men was on work release for possession of a stolen car, but the gunman’s appeal to race fell flat: they not only knew Roseland Christian Ministries, one of them knew Roger Nelson from his work there. After police arrived, a shaken Donna and Kent Van Zanten accompanied officers on a ninety-minute drive throughout the neighborhood while Roger and his fiancée went to a station house with detectives to look at photos of possible suspects.

Twelve days later, one of the car repairers identified a photo he believed matched the gunman; police also received an anonymous telephone tip that the man they wanted went by the nickname “Squeaky.” Detectives went to 10727 South Indiana Avenue, less than four blocks from the scene of Nelson’s murder, and told the older man who answered the door that they wanted to speak with Clarence Hayes. “Hey, Squeaky,” he called upstairs. Hayes wasn’t home, nor was he on five subsequent occasions when police stopped by, but on Sunday morning, April 14, the thirty-four-year-old three-time ex-convict and drug addict was arrested at a nearby currency exchange. That afternoon, Lavergne McDonald, Donna and Kent Van Zanten, and both of the car repairers picked Hayes out of a police lineup, as did Roger Nelson and his fiancée when they arrived in Chicago that evening.

Ronald Nelson’s murder—a white victim, a black gunman, a Sunday church parking lot—drew more news coverage than anything else that had happened in Roseland in years. Eighteen months later Clarence Hayes was convicted of murder and multiple counts of armed robbery and sentenced to death; after appellate review he was sentenced to life in prison. Over a quarter century later, he was still challenging his conviction in the courts, but on the thirtieth anniversary of Nelson’s murder Clarence Hayes remained safely ensconced in the maximum-security Stateville Correctional Center in Crest Hill, Illinois.

March 28, 1985, was the fifth anniversary of Wisconsin Steel’s sudden shutdown. Frank Lumpkin, now sixty-seven, was one of the few ex-workers whose more than thirty years at the plant meant he was collecting his full pension. Those not so fortunate received little if anything: Felix Vasquez, age fifty-seven, was receiving $150 a month for his twenty-four years of work. Lawyer Tom Geoghegan, whose lawsuit on their behalf against International Harvester was mired in the courts, told one reporter that men like Vasquez “were cheated by a company they gave their whole lives to.”

Thanks to ongoing support from the Crossroads Fund, Lumpkin’s Save Our Jobs Committee (SOJC) remained active, but in South Deering, the plant was now little more than “heaps of rusted scrap.” An anniversary rally drew only two hundred people, and one former worker told the Tribune that South Deering was now “a battered hulk of a neighborhood” strewn with “battered, empty hulks of men.” Now, five years later, no one at all doubted that “Black Friday” had indeed been “the end of an era.”

The former Wisconsin workers were not alone. At South Works, most of the south half of the mill had been demolished during the previous winter, and the remaining workforce was static at eight hundred. The Southeast Side’s third major mill, Republic Steel, on the East Side, had a storied history—ten striking workers had been shot dead by Chicago police on Memorial Day 1937. By the mid-1970s, however, it was known to suffer from a “morale problem,” and longtime United Steelworkers Local 1033 president Frank Guzzo “throws up his hands when discussing the increasing number of men who are drinking on the job.” The consequences were severe: in early 1976, 46 percent of the steel shipped from Republic was “rejected because it was not up to standards,” a problem Frank Lumpkin had also seen at Wisconsin.

As of early 1982 Republic had an active workforce of five thousand, but eighteen months later that number had been halved. Then, in early 1984, Republic was bought by the Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) conglomerate, which six years earlier had acquired Youngstown Sheet & Tube in Ohio. Guzzo tried to put a bright face on the move, but workers grew increasingly unhappy with Guzzo’s concessionary attitude. In April 1982, Guzzo had won reelection over a young challenger by a margin of 1,167 to 935 in a multicandidate field, but as the April 1985 election neared, a different outcome loomed.

Guzzo’s top challenger both in 1982 and three years later was thirty-year-old Maury Richards, a tall, physically imposing man who was attending law school part-time and who in 1984 had mounted a credible insurgent challenge against an East Side state legislator and bar owner who was a Vrdolyak lackey. When the April 1985 ballots were tallied at Republic, it was clear that an era had ended there as well when Frank Guzzo finished fourth with just 331 votes and Maury Richards prevailed with a plurality of 538. However dim the future might be for steelmaking on Chicago’s Southeast Side, the workers now had a new voice, one almost forty years younger than Frank Lumpkin.

As 1985 dawned for Jerry Kellman’s CCRC, Time for XII, and DCP trio, he and Ken Jania were joined by a third organizer, an old IAF colleague of Kellman’s named Mike Kruglik. A 1964 graduate of Princeton University, Kruglik had spent several years as a history graduate student at Northwestern University before shifting into organizing in 1973. He spent the mid-1970s working in Chicago, but by 1979 Kruglik was in San Antonio, Texas. Then, late in the fall of 1984, the Roman Catholic Church’s national Campaign for Human Development committed at least $42,000 to CCRC for 1985, and Kellman invited Kruglik back to Chicago to take the lead in building DCP. Several months later the Woods Fund, which had just designated community organizing as its “primary interest,” indicated that it would provide a further $30,000 to support CCRC and DCP salaries.

When Ken Jania was offered a much better paying job and left CCRC in March, Kellman asked Adrienne Jackson, who had been conducting parishioner interviews as a volunteer, to come on board full time, and she took up outreach to new churches. Mike Kruglik focused on expanding DCP’s reach across Greater Roseland; a public meeting at St. Thaddeus parish just south of 95th Street attracted both the 21st Ward alderman and Nadyne Griffin, an energetic woman in her late forties who had lived in the Lowden Homes town house project north of 95th Street for many years. She took an immediate liking to Kruglik, but other DCP members, who already found Kellman’s hard-driving style to be grating, thought Kruglik was just more of the same.

In late April or early May, the tensions came to a head. “My compadres felt Mike was kind of pushy,” St. Catherine deacon Dan Lee remembered. “So one night we had a little caucus, and it was just us. Mike wasn’t there, Jerry wasn’t there.” The small group agreed that “we are talking about black issues,” Dan recounted. “When we talk to Mike, it’s like we can’t get through…. We need a black person to be our mentor. We need a black person…. Let’s talk to Jerry.” Dan, Loretta Augustine, and Yvonne Lloyd went to Kellman. “Nothing against Mike, but we want somebody black over here because we are black,” Dan recalled. Kellman didn’t argue. “Okay, if that’s what you want, that’s what I’ll do.” From 1980 forward, the entire UNO and CCRC organizing effort had failed to employ an experienced black organizer; only parish volunteer Adrienne Jackson, just added to staff, was African American.

Kellman tried to make good on his commitment, but no plausible candidates could be found. “Jerry was busting his behind to find a black organizer,” CCRC’s Bob Klonowski recalled, but was “just having no luck.” Reluctantly, Kellman asked the DCP members to stick with Kruglik after all, but Loretta Augustine took the lead in saying no: “He’s not what we feel we need.” Loretta was “a very strong-willed person,” her colleagues knew, “very outspoken … if she didn’t like something, she let you know,” and her verdict on Kruglik was final.

But it was Father John Calicott, the African American associate pastor from Holy Name of Mary, who hammered the point home most forcefully. Calicott had seen the same pattern too many times before throughout the Chicago archdiocese. “I just had a problem with white folks always figuring that they knew more about what to do for us than we did,” he later explained. He had had the same reaction when he first met Kellman. Jerry was “well intentioned, really wants to do the right thing, but cannot hear,” Calicott recalled, and when Kellman had first introduced Kruglik to the DCPers, the same dynamic reoccurred. Calicott posed several questions, asking, essentially, “Are you willing to listen to our ideas?” In essence Mike replied, “ ‘Well, yes, but you know, this is the way we’ve done it before, and we know this is going to work.’ ” That “really left a bad taste in my mouth,” Calicott recounted.

When Kellman again asked them to accept Kruglik, and Loretta said no, Calicott spoke up to second Loretta’s refusal: “Let’s get somebody who knows us!” As Loretta vividly recalled, Calicott didn’t stop there. “The priest pointed his finger at Jerry, and he said, ‘I don’t know where you’re looking, but there’s got to be somebody out there who looks like us and thinks like us and understands our needs. So wherever you’ve been looking, you go back and look again.’ ” Yvonne Lloyd remembered those five words just as Loretta did: “go back and look again,” but “Jerry was livid,” Loretta recalled. Kellman insisted he would not jettison Kruglik, and Calicott said fine, but not for DCP. “The whole room was just absolutely quiet,” Loretta remembered, but Kellman agreed that he would look again.