По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

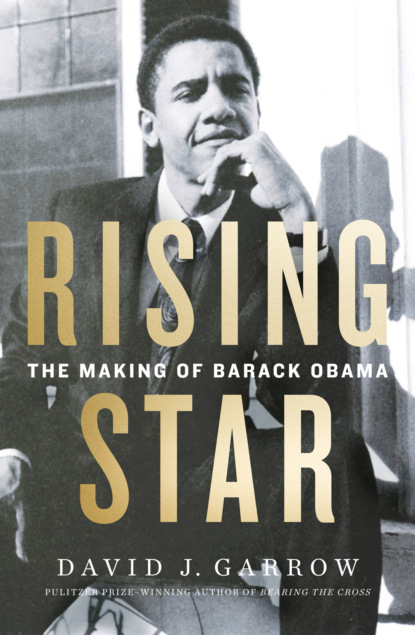

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Edley’s Ad Law was “almost as exciting as the Torts class” a year earlier with David Rosenberg. “Barack and I loved the Ad Law class” and “had a tremendous amount of fun” in it, Rob remembers, for Edley was “inspiring” and had “this very functional, argumentative intellectual approach.” The course “stimulated a lot of deep discussions,” plus a number of office-hours conversations with Edley, whom Rob thought was “truly a great teacher.”

Mark Kozlowski recalled that Tribe’s Constitutional Law had “a really lively atmosphere.” As in all sizable classes, seats were preassigned, and Scott Scheper, a 1988 summa cum laude graduate of Case Western Reserve University, found himself in a second-row aisle seat, at the front of the bowl-style classroom, with Obama just to his right. Like Scheper, Laura Jehl, a 1986 highest honors graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, had been in a different 1L section than Obama. But she already knew Tribe from her work on U.S. senator Edward M. Kennedy’s Judiciary Committee staff, and she was also already one of Tribe’s research assistants. Jehl took note of Obama from the outset of Tribe’s class. He “spoke up and said something eminently reasonable, eminently thoughtful,” and with an “absolutely amazing voice.”

Section III survivor Jennifer Radding remembered that Barack “was exceptional in Tribe’s class” and that “Tribe was like in love with him in a very intellectual way.” Sarah Leah Whitson witnessed it too. “Barack seemed to be operating at another level…. His rapport back and forth with Tribe felt more like a dialogue among equals.” Kevin Downey, a 1988 magna cum laude graduate of Dartmouth, noted how Obama spoke in “narrative-based” style that often included references to his own experiences, while Rob Fisher, who also stood out, made “more analytic comments.” Downey thought they “were leagues beyond the rest of us.”

Seated next to Obama, Scott Scheper had as close a view as anyone. Tribe was “a whole lot more theoretical” than he had anticipated, more interested in “What’s right? What should be?” than in “How is? What is?” Obama was “facile and adept,” and “talked more than any other single individual” in the class. Scheper recalled that “Tribe spent a whole lot of time not six feet from me in what almost became personal dialogue between him and Barack…. He would leave the lectern and come over … to our side of the class and be right in front of the front row and then Barack would be talking to him.” The scene made Scheper “sort of self-conscious that I had to maintain my posture because the whole class was looking right at me because that’s where the focus of the dialogue was.”

Several weeks in, Scheper’s demanding Trial Advocacy Workshop kept him away from Con Law for several classes. When he returned, Rob Fisher was in his spot, and Scheper realized that Obama “gave away my seat because I didn’t come to class.” Barack immediately apologized: “I thought you dropped the class.” Then the regular pattern resumed. Obama “was always engaged in these esoteric discussions with Professor Tribe…. They spent a lot of time talking about what the law should be.” All told, Rob explained, with Tribe plus Edley and Kraakman, fall 1989 “was a pretty fun semester.”

That fall was Robert Clark’s first as dean of the law school. The school had been in the news over the summer because of the arrest and suspension of an African American 3L accused of raping a Harvard undergraduate. But Clark played right into the hands of his detractors when he terminated the school’s public interest career counselor before the semester began. Clark called the move “a reorientation of resources” away from something that served only “symbolic, guilt-alleviating purposes,” but progressive students reacted immediately. A protest rally attracted a crowd of three hundred, with Barack’s close friend Cassandra Butts telling the Harvard Law Record, “I came to law school in particular because I was very much interested in helping people who don’t have access to the law and who see the law as being more of a hindrance than a help to them.”

Students viewed Clark’s move as a tangible, public rebuke of those motives, and quickly created the Emergency Coalition for Public Interest Placement. National legal publications and the Boston Globe all covered the controversy, but the Harvard Crimson highlighted how tiny a percentage of Harvard Law students actually took public interest jobs once they graduated. Butts told the Crimson that many students arrived with such an interest, “but with the emphasis here on corporate law, they don’t always leave with that attitude.” Given the “insurmountable number of loans they need to pay off,” students may “choose to go into corporate work, but they will be more sensitive to the need for pro bono lawyers.” As the fall semester progressed, eight hundred law students signed letters protesting Clark’s move, then dumped them outside the dean’s office during a one-hundred-person rally that the Record said had “an emotional, near confrontational tone.” As Christopher Edley ruefully recalled, Clark “was screwing up massively.”

In late September, Barack flew back to Chicago to take part in a Friday-afternoon roundtable discussion on community organizing. Funded by Ken Rolling and Jean Rudd at Woods, the event built on the commissioned essays Obama and others had written for Illinois Issues a year earlier. Sokoni Karanja, Wieboldt’s Anne Hallett, and several local academics were part of the group, and, as he had in other settings, Barack refrained from talking until the discussion was well under way. When he did speak, Barack highlighted what he called “the educative function of organizing,” for “at some point you have to link up … with the larger trends, larger movements in the city or the country. I think we are not very good at that.” He suggested that “I am not sure we talk enough in organizing” about organizing’s internal culture, and “we don’t understand what the relationship between organizing and politics should be…. I would like to think that ideally you would focus on the local but educate for the broader arena, and that you are creating a base for political or national issues.” Barack expressed disappointment that organizing had a “suspicion of politics,” for “politics is a major arena of power” and “to marginalize yourself from that process is a damaging thing, and one that needs to be rethought.” His critique was fundamental, and strong. “Organizing right now doesn’t have a long-term vision.”

In the 1960s, “a lot was lost during the civil rights movement because there was not enough effective organizing consolidating those gains,” but now organizers were ignoring the potential of working with movement-style efforts, and “that long-term vision needs to be developed.” Barack returned to organizing’s educative mission. “How do you educate people enough so that they can be forcing their politicians to articulate their broader views and wider horizons?” he asked. “People expect politicians to express some long-term interests of theirs and not just appeal to the lowest common denominator.”

Barack sat back before again weighing in. “There is this big slippery slope of folks and communities that are sinking,” he reminded the group. How can organizing help them? “How do you link up some of the most important lessons about organizing … with some powerful messages that came out of the civil rights movement or what Jesse Jackson has done or what’s been done by other charismatic leaders? A whole sense of hope is generated out of what they do. Jesse Jackson can go into these communities and get these people excited and inspired. The organizational framework to consolidate that is missing,” especially given the lack of minority organizers. “The best organizers in the black community right now are the crack dealers. They are fantastic. There’s tremendous entrepreneurship and skill,” all being used to distribute illegal drugs. To help black neighborhoods, “organizing in these communities … can’t just be instrumental … it has to be recreating and recasting how these communities think about themselves.”

After a pause, Barack turned to one of his chief takeaways from his time in Roseland. Harold Washington “was an essentially charismatic leader,” although “his election was an expression of a lot of organizing that had been taking place over a long time.” All indications were that “to a large extent” Washington “wanted to give back to that process. He wanted to give those groups recognition and empower them in some sense,” as he had done so visibly with Mary Ellen Montes and UNO, but “real empowerment was not done.” An African American historian on the panel objected to Barack criticizing Harold Washington. Sokoni Karanja agreed with the angry historian, but Anne Hallett sided with Barack, who pursued his point. “When you have a charismatic leader, whether it’s Jesse Jackson or Harold Washington … there has to be some sort of interaction” that moves all that energy back “into the community to build up more organizing … more of that needs to be done.” Then the conversation shifted, but Obama made one final point: “Organizing can also be a bridge between the private and the public, between politics and people’s everyday lives.”

Barack’s comments revealed how profoundly he disagreed with the worldview of IAF and Greg Galluzzo, and how convinced he was that social change energies should be focused on the political arena. In later years hardly anyone would appreciate the significance of what Obama said that day. Ben Joravsky, a fellow participant who was already on his way to becoming one of Chicago’s most perceptive political journalists, later recalled Obama’s “veneer of cool” but dismissed his comments as those of “a windy sociology professor with nothing particularly insightful to say.” Only journalist John B. Judis, examining this moment many years later, would highlight how Obama had voiced “a litany of criticisms of Alinsky-style organizing” and note that he had “rejected the guiding principles of community organizing: the elevation of self-interest over moral vision; the disdain for charismatic leaders and their movements; and the suspicion of politics itself.” But, Judis wrote, Obama “did so in a way that seemed to elude the other participants,” who objected only to Barack’s remark that Harold Washington had not left behind any tangible political legacy.

Judis mused that even Obama “seemed initially oblivious to the harsh implications of his own words,” but Washington’s fundamental failure should have been obvious to everyone in the room, especially because the mayor’s political base had so quickly fallen apart after his death, leaving Chicago with a white, Democratic machine mayor with an all-too-familiar surname. Six months earlier, Cook County state’s attorney Richard M. Daley had defeated Gene Sawyer in the Democratic primary by 55 to 44 percent, and five weeks later, Daley was elected mayor, besting Alderman Tim Evans, running as an independent, by 55 to 41 percent. Ed Vrdolyak, now a Republican, garnered 3 percent and soon added a sideline as a radio talk show host to his lucrative South Chicago law practice.

The Chicago trip was also a chance for Barack to spend a weekend with Michelle Robinson, and either then or soon after, he asked her to accompany him to Honolulu over the winter holidays. Back in Cambridge, Barack kept his distance from the burgeoning student protest campaign, despite his friendship with the outspoken Cassandra Butts, who, second only to Rob Fisher, was his best friend in Cambridge. Laura Jehl, who was working with Cassandra on a manuscript for the Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, knew that Barack and Rob were “inseparable,” and she also saw how Barack and Cassandra “were around together a lot but they didn’t appear to be together,” as she put it. “It did not seem to be romantic” and “it did not appear to be sexual.” Another female friend concurred: “the vibe they gave off was fraternal.” Laura thought that as attractive as Barack was, “there was also absolutely no body language of him that I was aware of towards anybody,” and other women all agreed: “I didn’t see any sexual energy from him” said one, and “never any sense” at all, recalls another.

On evenings when Barack worked on the Anthony Cook manuscript at Gannett House, he and fellow 2L African American editor Ken Mack often walked to a sandwich shop in Harvard Square for dinner. On several nights, Gordon Whitman gave Barack a lift home and spoke about how he was volunteering at the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance, a Boston group headed by veteran community organizer Lew Finfer. After Barack mentioned his Chicago experience, Whitman told Finfer he should meet him. Finfer called Obama, and they met up one day at a Harvard Square coffee shop. Finfer found Barack “cool” and “dispassionate,” but hoped to interest him in a return to organizing after law school. Barack politely said no. “I have a plan to return to Chicago and go into politics.”

One mid-October night, 3L executive editor Tom Krause, a U.S. Navy veteran who was overseeing the group edit of the Anthony Cook article, hosted a party following a lecture by Alex Kozinski, the well-known federal appellate judge for whom Krause would be clerking after graduation. Krause invited a number of editors of all political persuasions, and Barack attended. Review editors were prized candidates for clerkships with top federal judges like Kozinski, and an astonishing 102 members of the law school’s 1989 graduating class had won clerkships. Each fall 2Ls began eyeing and discussing which jurists they would apply to in the spring, and Ken Mack was astounded when Barack told him one evening that he was so focused on returning to Chicago after graduation that he would forgo applying for clerkships. When this news spread among African American students, there was open disbelief that such a top performer would pass up so prestigious an accolade. Kenny Smith was surprised and impressed, but others sensed an attitude of group disappointment. As Frank Harper put it, there were “these steps you’re supposed to take” and “people thought that he was making a catastrophic error by not clerking.”

Obama was a semiregular presence at BLSA meetings and parties. Cochairing a BLSA committee made him a formal member of BLSA’s executive board, but the group’s style was decidedly informal, with its annual spring conference the one major event requiring time and attendance by its members. After some BLSA gatherings Barack, Ken, and basketball buddies Frank Harper and David Hill would go to a pizza parlor on Mass Ave a bit north of the law school. Often joining them were two new 1Ls. Karla Martin was an African American 1987 Harvard College graduate; Peter Cicchino was white, gay, a year older than Barack, and had spent six years as a lay member of the Jesuits. Cicchino would become a defining member of the school’s public interest community and a landmark figure in the public emergence of gay people at Harvard Law. Karla remembers Barack saying that he “wanted to be a change agent” notwithstanding his absence from student protest ranks. “It was clear he had ambitions,” but “how that was going to play out was not clear.”

Barack continued to spend more time on the basketball court than he did just hanging out. The new 1L class brought some new faces plus a familiar one into Hemenway gym’s late-afternoon mix. Nathan Diament, an honors graduate of Yeshiva University, was short and fast. Greg Dingens had played defensive tackle at Notre Dame and three times won Academic All-American honors before graduating magna cum laude in 1986. Tom Wathen had been NYPIRG’s executive director during Barack’s four-month stint at City College four years earlier. Wathen recalled that they both did “a double-take” when they first saw each other. Compared to early 1985, when Barack was twenty-three years old, he of course seemed “more sophisticated” now at twenty-eight. “I was very impressed with him,” Wathen remembered.

One day early that fall, Frank Harper, cochair of BLSA’s community outreach committee, read a letter sent to the BLSA by Ronald A. X. Stokes, an inmate at Massachusetts’s maximum-security state prison at Walpole, about thirty miles south of Cambridge. According to Harper, Stokes’s message was a challenge: “you black students at Harvard should be ashamed of yourselves. There’s a huge African American prison population; we never see hide nor hair of you.” Harper called him at the prison and then “he calls me collect.” Stokes sounded “very sincere” and mentioned that “we play a lot of basketball at Walpole.”

That gave Harper an idea: “Let’s have a basketball game.” Harper called the warden, who thought, “This is very odd,” but agreed to allow it if Harper could recruit five Harvard players. “Then I approach Barack. ‘This isn’t going to be an easy task,’ ” but they recruited black classmate Andre Nobles, a white Hemenway player, and a black poli sci grad student. A date was set, a van was rented, and when they arrived at Walpole, the warden gave them a stern briefing. “You’re entering general population” and guards “are not going to be down there with you,” only in sentry towers, Harper remembered. “If something happens, go to the corners, because we won’t fire shots in the corners.”

For the inmates, the game was major entertainment. “The entire prison surrounded the court to watch” as “the Walpole All-Stars” hosted five nervous Harvard gym rats. “We had a good team,” Harper recalled, and “it was definitely a competitive game,” at least until halftime. The Harvard players later joked that Obama played well until he asked the inmate who was guarding him what he was in for. “The brother said double murder, and Barack didn’t take another shot,” Harper remembered. “They won the game,” but the inmates were grateful for the students’ visit. Stokes told Harper that “he was getting out” within a few months, and “I stayed in contact with him after the game.”

By November, Rob and Barack’s relationship with Larry Tribe had far outstripped the normal research assistants’ role, especially for first semester 2Ls. The lead piece in the Harvard Law Review’s November issue was an essay by Tribe, rather than the annual foreword, and on page one, Tribe’s first footnote stated that “I am grateful to Rob Fisher,” top 3L Michael Dorf, two postgraduates, “and Barack Obama for their analytic and research assistance.” It was a remarkable commendation, and Tribe had already invited Fisher and Obama to enroll in a spring seminar, limited to fifteen students, that would further consider the ideas expressed in his thirty-nine-page Review essay, “The Curvature of Constitutional Space: What Lawyers Can Learn from Modern Physics.”

Tribe’s description of the seminar invoked two contrasting conceptions of the U.S. Constitution: first that the original 1787 document was “Newtonian” in its promulgation of three branches, featuring “carefully calibrated forces and counter-forces,” and second, that the twentieth-century idea of an evolving “living Constitution” was Darwinian. Tribe proposed exploring a third conception, one modeled upon the work of physicists Alfred Einstein and Werner Heisenberg, “focusing on how observers alter the nature of what is observed” and considering “the concrete geometry of the space-time continuum.”

As obscure as that might sound, Rob and Barack were hooked after listening to Tribe at a late-October “organizational meeting” that began to sketch out what the selected participants would tackle. Rob wrote to Tribe that he had a “particular interest in … [t]he nature of the enterprise itself, that is, Law: This is the main focus of my thinking right now. Barack and I have been working on a meta-theory of the law—let’s call it post-modern epistemology. (Though Barack hasn’t seen this memo, so don’t blame him for anything in it.) I will be looking at the Constitution as both a test for and an inspiration to that meta-theory … the role I see it potentially playing in the seminar is as a gadfly to your physics metaphor” but “not necessarily inconsistent” with it. It was no wonder that classmates marveled at Barack’s “esoteric discussions” with Tribe and felt that he and Rob “were leagues beyond the rest of us.”

At the Law Review, editing work continued on the dense Anthony Cook article, which would not be published until March. The November issue that featured Tribe’s essay also contained the traditional foreword, authored by Erwin Chemerinsky of the University of Southern California, and case comment, by Frances Olsen of the University of California at Los Angeles. One 3L editor had been hugely impressed by Chemerinsky, a mesmerizingly intense speaker, and successfully lobbied for his selection for that prized role. Olsen was a well-known feminist scholar who had published a major article in the Review six years earlier. Her piece had undergone a very difficult edit, including the editors’ insistence that the Review would not publish the word “bitch.” As 2L editor Susan Freiwald, who witnessed one exchange, said, Olsen’s experience at the “P-read” stage exemplified how Review president Peter Yu “thought he was smarter than everyone else, including professors.” Yet as 3L Articles Office cochair Andy Schapiro stressed, the perception that Yu was indeed “the smartest” had been the decisive factor in his election as president nine months earlier. Editor Pauline Wan, a 3L, agreed. “People wanted to elect the smartest person in the room,” and “everyone felt Peter was the smartest person in the room.”

But Yu’s presidency was getting decidedly mixed reviews. During the summer, he had overseen the installation of a new computer system for the Review, but as the fall commenced, tensions grew. Chad Oldfather, who worked up to twenty hours a week at the Review as a work-study undergrad, remembered Yu as “not a warm and fuzzy guy,” and 3L editor Barbara Schneider realized that he was “not a people person.” Pauline Wan found him “remote,” and Brad Berenson, one of the most involved 2L editors, felt Yu was “a slightly aloof figure.” Kevin Downey, an active 2L, thought Peter was “not at all approachable” and “not a good leader.” Supreme Court Office cochair Frank Cooper, one of four African American 3Ls, viewed Peter as “a quiet intellectual who was focused on the academic rigor” of each issue, but “he was not even a quiet leader.”

Yu had a particularly strained relationship with Articles Office cochairs Gordon Whitman and Andy Schapiro, both of whom were lefty-liberals, in part over their selection of articles like the one by Anthony Cook. Susan Freiwald remembered Yu editing one piece and remarking that “every good idea in here comes from me.” But Freiwald thought Yu’s interactions with Frances Olsen were inexcusable, that he was “intellectually beating up” on her. During one loud, angry phone exchange, Freiwald remembers Yu “just screaming at her and her screaming back,” and it left Freiwald thinking that “Peter was an asshole.”

As the editing of the Cook manuscript proceeded, more and more of the work fell to Christine Lee. Articles Office member David Goldberg, a 2L, realized the piece “was way too long” and “a little jargony,” and fellow 2L editor John Parry saw that Christine “worked very hard” and “reorganized it, and I think made it coherent.” Christine willingly put in lots of time, but as the semester progressed, she concluded that Barack was more interested in playing basketball than doing his share of the necessary sub-citing and other work on the Cook manuscript. “We were a team,” but “he would play basketball religiously, including when there was a sub-cite due,” Christine remembered. “He definitely did the bare minimum,” and “it was just building my resentment” as “other people were covering for the drudge work he wasn’t doing.”

Executive editor Tom Krause noted that at the outset, “Barack was like the primary editor,” but “somehow it kind of was taken over by Christine, who ended up doing all the work.” Krause was not a fan of the article, but in his eyes, Christine, “to the detriment of her own grades and class work, was doing work he”—Obama—“could have been doing.” As the piece moved forward, Krause stepped up his own involvement, and he and Christine—polar political opposites—became personally close “doing the things that Barack had not done,” Christine recalled. In retrospect, even Gordon Whitman, Cook’s main proponent, realized the article was “pretty impenetrable.” Krause thought “it would have been worse if Christine and I hadn’t worked on it,” but Whitman’s verdict was appropriately biting: “In hindsight, what the hell was that all about?”

The real meat of each November issue was the individual case comments, which were anonymously authored by 3L editors. The 1989 issue surveyed twenty-five Supreme Court decisions, which brought the issue to a robust 404 pages. This earned Peter Yu a stern rebuke from Erwin Griswold: “I would like to suggest that one of the major tasks of the President is to edit out vast quantities of unnecessary words, and to keep the overall size of each issue, and of the volume, under control.” Yu responded that he shared that concern, but he cited “the extraordinary number of leading cases from this past Term” and promised that the entire volume would not be any larger than in years past.

Griswold replied that he was “not wildly enthusiastic about” the Tribe essay; “essentially the same arguments can be made without any … farfetched allusions to concepts developed in the field of physics.” In contrast, Griswold found Chemerinsky’s foreword “both interesting and powerful” and thought Olsen’s comment was “imaginative and stimulating.” He thought some of the case comments were “very good,” but “surely much too wordy.” Griswold was happy that the December issue, at 196 pages, would be less than half the size, but again he said the sole article, a 105-page piece on statutory interpretation, was “awfully wordy.” A thirty-one-page review of a book by philosopher Richard Rorty was “much too long” and “quite indigestible,” a “depressing” example of something “written by a professor for the professors” rather than for “active, practicing lawyers.”

Griswold was happy with the two six-page “Recent Cases” summaries, one of which, by Barack’s basketball buddy Tom Perrelli, a 1988 magna cum laude graduate of Brown, exemplified how 2L editors were expected to do at least one brief piece of individual writing in addition to their pool or team assignments. Barack may not have been doing his share of the work on the Cook edit, but by late October, he was well under way writing a comment on a late 1988 decision by the Illinois Supreme Court, which held that a young child injured in an auto accident while she was still a fetus cannot sue her mother for monetary damages. Laurence Tribe was completing work on a book surveying the ongoing U.S. political debate over abortion, and Barack was one of more than a dozen of his research assistants whom Tribe had asked to read and summarize relevant materials.

Barack mentioned the case comment he was writing to his mother at the same time he told her that, unlike the previous year’s Christmas holiday, he was coming to Honolulu and Michelle Robinson was coming with him. Maya had not returned to Barnard for her sophomore year and had joined her mother in Jakarta before returning to Honolulu, where she was waitressing at a restaurant. Barack had not seen his mother, who was now forty-six years old, since Christmas 1987, when he had taken Sheila Jager to Hawaii to meet his family. Just after he started at Harvard, Ann had moved back to Jakarta to take a job at the People’s Bank of Indonesia—Bank Rakyat Indonesia, or BRI—the country’s oldest financial institution and one specializing in microfinance, small loans to artisans and retailers. Ann had lost interest in completing her long-delayed dissertation, telling her old friend Julia Suryakasuma that “the creative part was over long ago, and it’s just a matter of finishing the damn thing.”

But her new work put her in direct contact with the people whose artisanal pursuits she had devoted her fieldwork to studying. Ann also had begun a fulfilling relationship with Made Suarjana, a married journalist eighteen years her junior, and in November, she wrote to Alice Dewey, her longtime mentor, to tell her that she would be returning to Honolulu for the holiday. She told Dewey that Maya’s time in Indonesia “seems to have done her a lot of good, unstressed her and renewed her self-confidence” after a rocky first year at Barnard. “Barry is also coming at Christmas with a new girlfriend in tow. He is still enjoying law school and writing pro-choice opinions of the abortion issue for the Law Review.”

No matter what Barack told his mother about his case comment, which went to press in early December, its pro-choice stance was extremely measured. The Illinois court had defended its holding on the grounds that otherwise the mother and her fetus would be “legal adversaries from the moment of conception until birth.” Obama commended the court for its “thoughtful approach” and wrote that the case “highlights the unsuitability of fetal-maternal tort suits as vehicles for promoting fetal health.” He said the suit “also indicates the dangers such causes of action present to women’s autonomy, and the need for a constitutional framework to constrain future attempts to expand ‘fetal rights,’ ” because “fetal-maternal tort suits affect even more fundamental interests of bodily integrity and privacy” on the part of women. He wrote that the state may have “a more compelling interest in ensuring that fetuses carried to term do not suffer from debilitating injuries than it does in ensuring that any particular fetus is born,” but again stressed the primacy of “women’s interests in autonomy and privacy.” Obama concluded the piece by recommending that “expanded access to prenatal education and health care facilities will far more likely serve the very real state interest in preventing increasing numbers of children from being born into lives of pain and despair.”

Before fall classes ended on December 8, two Chicagoans visited the law school. Elvin Charity, a 1979 Harvard Law graduate who had worked for Harold Washington, was now one of two black partners at the Chicago law firm of Hopkins & Sutter. Charity was on his firm’s recruiting committee “to help to promote the hiring of African-American lawyers,” and Harvard was an annual target. Second-year students traditionally split their summers between a pair of firms, and although Barack would return to Sidley & Austin for part of the upcoming summer, Hopkins & Sutter was another attractive Chicago firm. To Charity, “Barack was particularly striking” in part because he showed up for his interview “pretty casually dressed,” rather than in a suit and tie. “He just seemed so nonchalant about the whole thing,” with “a calmness and a seeming maturity beyond his years.” Charity knew the significance of Barack’s Law Review membership, but Obama “did not seem to be full of himself” and an offer was quickly extended and accepted.

The second Chicago visitor was Michelle Robinson, who along with an Asian American colleague was there on behalf of Sidley to speak to minority 1Ls about job search techniques at an evening session sponsored by all three ethnic—black, Latino, and Asian—student groups. Several ’91 and ’92 BLSA women who had heard Barack talk about Michelle realized this would be a perfect opportunity to “go see who this person is,” and “we were very impressed with her,” Jan-Michele Lemon remembered. “She was very engaging and warm and friendly.”

Michelle’s Wednesday visit came just two days before the end of classes, and the next Monday Barack faced the first of three fall semester final exams. Upper-class exams took place in December, not mid-January, but Barack had Edley’s Ad Law and Tribe’s Con Law take-homes back-to-back on the first two days of exam period. Edley’s emphasized that “it is important to demonstrate that you have synthesized the assigned readings and course materials,” and students had to answer six out of nine questions, with responses limited to 150 to 500 words apiece.

Tribe’s open-book final posed just one essay question, with answers limited to 1,750 words. The hypothetical situation involved an abortion clinic employee who had been fired for telling a woman the sex of her fetus. The woman then aborted the fetus, citing avowedly religious reasons, because it was female. The fired employee had been denied unemployment benefits, and Tribe’s hypothetical played off a recently argued U.S. Supreme Court case, Employment Division v. Smith, which also involved a state’s refusal of unemployment benefits to a worker fired because of religion-based conduct. Tribe asked students to write their best decision of the case. Six days later, on December 18, Barack and Rob had their last fall exam, for Kraakman’s Corporations class. Then Barack was free to head to Honolulu, though upper-class students’ single winter session course would begin promptly on Tuesday, January 2.

Barack’s introduction of Michelle Robinson to Ann, Toot, Gramps, and Maya signified, just like Sheila’s visit two Christmases earlier, how serious this six-month-old relationship was. After Michelle’s early December visit to Harvard, “it was clear that they were ‘a couple,’ ” her close Sidley friend Kelly Jo MacArthur recalled, and “the discussions turned fairly soon to whether they were going to get married or not.” That clearly came up during their time together in Honolulu, because soon after they flew back to the mainland, Ann Dunham sent her close Indonesian friend Julia Suryakusuma a description of Michelle. “She is intelligent, very tall (6'1"), not beautiful but quite attractive. She did her BA at Princeton and her law degree at Harvard. But she has spent most of her life in Chicago,” so she was “a little provincial and not as international as Barry. She is nice, though, and if he goes ahead and marries her after he finishes law school, I will have no objections.”

Almost the first day he returned to Cambridge, Barack wrote to Sheila Jager, who two months earlier had returned to the U.S. from South Korea. Barack had written to Sheila regularly throughout her time abroad, once sending her a short story he had written and another time “an annotated copy of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.” By the time she returned, Sheila had told Barack she had applied for and won a Harvard teaching fellowship in Asian Studies with the eminent scholar Ezra Vogel. Before the end of January, Sheila would be moving to Cambridge and renting an apartment at 5 Crawford Street. She recalled that “the job at Harvard had nothing to do with Barack being there, per se, although I can’t rule out that I unconsciously applied to Harvard to be near him.” But she also explained, “Then again, I wasn’t going to turn down a job there simply because he was there,” and during their time apart, she had begun a relationship with someone else.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: