По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

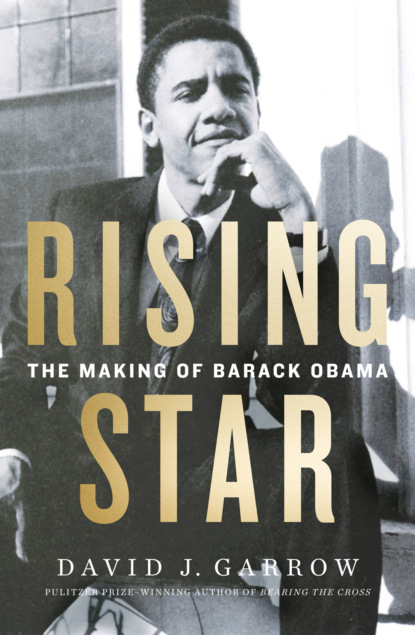

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Several hundred graduating students had completed a Robert Granfield questionnaire that probed that subject, and a heavy majority acknowledged that “the necessity of repaying educational loans” had been a decisive factor in their own job decisions. With most graduates leaving Harvard saddled with tens of thousands of dollars in debt, law students “are co-opted into futures of providing service for the corporate elite,” Granfield concluded. Verna Myers had arrived at the law school straight from her 1981–82 senior year as president of Columbia and Barnard’s Black Student Organization. “I went to Harvard expecting to change the world,” but in 1985, “I left Harvard thinking ‘How can I pay my loans?’ ”

The first day of Harvard’s fall 1988 registration for 1Ls featured a 1:00 P.M. financial aid session. Tuition for the year was $12,300, with total costs for a student living off-campus estimated at $22,450. That day or the next, the new students also received their course schedules for the fall semester. The entering class was divided into four numerically identified sections—I, II, III, and IV—of about 140 students apiece. Each section had five core first-year courses: Civil Procedure, Contracts, Torts, Criminal Law, and Property. Within each of those four sections, each student was also assigned to a thirteen-member “O Group”—O as in Orientation—which would then become their ungraded, fall semester one-afternoon-a-week Legal Methods class, taught by an upper-class student. Each O Group had a faculty mentor, and for Section III, to which Obama was assigned, one of the five substantive courses, Torts, would be divided into a trio of smaller, forty-five student classes. For Section III, Civil Procedure and Contracts would last the entire year, three hours a week. Torts and Criminal Law would meet five hours per week in the fall semester. In the spring, when 1Ls could choose a single elective from among half a dozen choices, Section III would have Property five hours per week, and the Legal Methods class would morph into a prolonged “moot court” exercise in which two-person teams briefed and argued faux court cases. One odd feature of Harvard’s first-year schedule was that final exams for the fall classes took place only in mid-January, well after the Christmas and New Year’s break.

The first classmates the new students met were their fellow members of the O Group, who introduced themselves alphabetically. Richard Cloobeck was a twenty-two-year-old Dartmouth graduate from Los Angeles. African American Eric Collins, from North Carolina, had just graduated from Princeton. Twenty-three-year-old UCLA graduate Diana Derycz had just finished a master’s degree at Stanford. Then came a trio of visibly older men. Rob Fisher had grown up on a farm in Charles County in southern Maryland before graduating from Duke in 1976 and completing a Ph.D. in economics there six years later. From 1982 until a few months earlier he had taught economics at the College of the Holy Cross in western Massachusetts. Mark Kozlowski, a 1980 graduate of Sarah Lawrence College, had spent the past eight years studying political theory at Columbia University and was about to submit his Ph.D. dissertation on the constitutional thought of American framer and president James Madison. When Barack Obama introduced himself, “the way he spoke was very, very memorable,” Richard Cloobeck recounted. “He was talking about black folks and white folks” and “what really, really struck me is that I got the impression he was neither.” Mark Kozlowski remembered Barack mentioning both Hawaii and Indonesia when he spoke. “I was immediately very impressed with Barack” and “I was immediately taken with the voice.” The trio of Fisher, Kozlowski, and Obama made Cloobeck realize “there was a big distinction between the older people and the younger people,” and Diana Derycz remembered similarly, thinking “how brainy people were” in this new northeastern environment.

After Obama was a twenty-two-year-old Tufts graduate. “I’m Jennifer Radding. I have no idea how I got in,” she said. She remembers that Barack was among those who laughed, and “he knew I was a bit of a jokester,” Jennifer explained. Jeff Richman had just graduated from the University of Michigan, and Sarah Leah Whitson was a brand-new graduate of UC Berkeley with family roots in the Middle East. The high-powered group featured strikingly diverse experiences. Diana Derycz had spent five years in Mexico as a child and was working part-time as a professional model. Fisher had studied in Australia for three years during and after graduate school, Barack had lived almost three years in Indonesia, and Whitson had spent summers with relatives in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon.

O group instructor Scott Becker, a twenty-five-year-old 3L who was a graduate of the University of Illinois, found himself supervising a group of 1Ls some of whom—Rob, Mark, and Barack in particular—were older and more worldly-wise than he. The first day’s mandate was to conduct some sort of attorney-witness Q&A exercise, and when it was over, Barack immediately introduced himself to the obviously brilliant Rob Fisher, who was seven years his senior. “We instantly became friends,” Fisher recalled. Rob’s intellectual enthusiasm and energy belied his thirty-four years. In 1986, New York University Press had published his book The Logic of Economic Discovery: Neoclassical Economics and the Marginal Revolution. The book’s title purposely mirrored Karl Popper’s famous The Logic of Scientific Discovery, and the major figure in Fisher’s work was the late Hungarian philosopher of science Imre Lakatos, whose scholarly work in Popper’s empiricist tradition was vastly better known than his role as a hard-core Stalinist in Hungary’s post–World War II Communist Party. Fisher’s focus was what he termed “A Lakatosian Approach to Economics,” and his volume had garnered enthusiastically positive reviews in scholarly journals. “The book effectively demonstrates the applicability of the philosophy of science to the history of economics,” one reviewer wrote, adding that “the argument is crystal clear and largely persuasive.” A second observed that “the reason neoclassical economists like Lakatos so much is that his philosophy is intended fundamentally to explain the evolution of physics,” since “neoclassical economics wants desperately to be a social physics.”

Fisher remembered from the first day that Barack “recognized he was in a playground for ideas,” one where he could exercise “his love for intellectual argument.” It was a passion that Rob shared, and from that day forward the somewhat unlikely duo would become an inseparable pair whom scores of classmates recall as the closest of friends. Barack remembered his initial experience of Harvard Law School similarly. “I was excited about it. Here was an opportunity for me to read and reflect and study for as much as I wanted. That was my job,” and a much easier one than what he had confronted at the Developing Communities Project. “When I went back to law school, the idea of reading a book didn’t seem particularly tough to me.”

The four fall 1L courses gave Barack some large books to read, and he needed to read them with painstaking care. In Contracts, Professor Ian Macneil, a 1955 Harvard Law School graduate who was visiting for the year from Northwestern University, had assigned his own Contracts: Exchange Transactions and Relations, 2nd ed., which was more than thirteen hundred pages long. In Civil Procedure, the text for the year, Richard H. Field et al.’s Materials for a Basic Course in Civil Procedure, 5th ed., came in slightly shorter, at 1,275 pages. Section III’s fall semester of Civ Pro was taught by Professor David L. Shapiro, a 1957 summa cum laude Harvard Law graduate and former Supreme Court clerk, but in December Shapiro would become deputy solicitor general of the United States, and the course would be taken over for the spring semester by Stephen N. Subrin, a visiting professor from Northeastern University Law School.

In Criminal Law, Professor Richard D. Parker, a 1970 Harvard Law graduate and another former Supreme Court clerk, assigned Paul H. Robinson’s brand-new Fundamentals of Criminal Law, a mere 1,090 pages. And in Torts, Professor David Rosenberg, a 1967 graduate of NYU’s law school who had taught at Harvard since 1979, would use Page Keeton et al.’s Cases and Materials on Tort and Accident Law, which at 1,360 pages was the bulkiest of the four.

After the long Labor Day weekend, 1L classes commenced on Tuesday morning, September 6. For Section III, their first class session was Contracts with Ian Macneil, whom the members of Barack’s O Group had already met for a brown-bag lunch in his role as their faculty mentor. Since Macneil was almost as new to Harvard as they were, the assignment had little practical value, but the Scottish Macneil—in private life he was the eminent forty-sixth chief of Clan Macneil—seemed like a nice man.

But in the classroom, Macneil’s use of the traditional Socratic method brought out an utterly different personal demeanor. Most members of Section III would remember their first class at Harvard Law School for the rest of their lives. They had been informed five days earlier, in the semester’s initial number of the weekly, mimeographed HLS Adviser newsletter, by both Macneil and David Shapiro, what to read in advance of Tuesday’s classes. Macneil’s reading included the preface to his casebook, in which he repeatedly used the Latin abbreviation “e.g.” and also stated his somewhat iconoclastic definition of the course’s core concept: “contract encompasses all human activities in which economic exchange is a significant factor—marriage as much as sales of goods.” That highly inclusive definition distinguished his text from others. “Thus the range of activities treated goes beyond those traditionally associated with the doctrinally structured first year contracts course.” Organized with an eye toward “functional patterns, rather than doctrinally,” the book “focuses on the negotiational and remedial processes that continuing exchange relationships generate.”

Ian Macneil began Tuesday’s 9:00 A.M. class by telling Section III’s 140 students that no matter where they had gone to college, no undergraduate education had taught them to read as carefully as they would have to in order to succeed at Harvard Law School. “For example, I bet you don’t know what the difference between i.e. and e.g. is,” he remarked while glancing at his seating chart and randomly calling upon Alicia Rubin, a 1987 graduate of Harvard College.

Rubin knew enough Latin to nail the answer cold: “i.e. stands for id est, that is, and e.g. is exempli gratia, for example,” she replied. “That really ticked him off,” she recalled, because Macneil had not anticipated an immediate correct response. “Well, Miss Rubin,” he said, “let’s see if you’ve done the reading for today. Can you define a contract?” Rubin “had not even bought my books yet,” and “so I fumbled around” trying to answer. Seated next to her was Michelle Jacobs, a 1988 Harvard College graduate who quickly realized that John Houseman’s fictional contracts professor in the 1973 film The Paper Chase was, at least in Ian Macneil’s classroom, no Hollywood exaggeration. “Oh my god! It really does happen!” Jacobs remembered thinking.

Jacobs knew that Macneil “had this bizarre definition of contract that was in our reading,” and “I had written it down, and I kept trying to give it to her,” but Rubin was focused only on Macneil. “Then he said something to the effect of ‘Don’t embarrass yourself further. Please leave the room, do the reading you were supposed to do, and then come back and see if you can take a better stab at it.’ ” David Attisani, a 1987 graduate of Williams College, watched the exchange and thought it “idiotic.” So did Eric Collins, the African American Princeton graduate who was in Obama’s O Group. He recalls thinking that “if this is how law school is, I’ve made a mistake.” Rubin said she rose, “borrowed somebody else’s textbook,” and headed for the door. Richard Cloobeck also remembered the scene. “It was a very, very powerful moment, and he was such an asshole.”

In the hallway, Rubin read through the preface of Macneil’s casebook. “It seemed like an eternity, but it probably was only ten or fifteen minutes.” She went “back into the room,” and “then he calls on me again.” Rubin tried “to stumble through some kind of response,” but Macneil “picked me apart again.” She felt “absolutely mortified and miserable,” but finally the class ended. “It was just a horrible first day of class,” Rubin recalled, but a few minutes later, in a nearby hallway, an older student she did not know came up to her. “He put his hand on my shoulder and was like ‘You know, you did a really nice job.’ ” He introduced himself as Barack Obama. “He was giving me this little pep talk,” and Ali Rubin was hugely appreciative. Barack’s comments were “really nice.”

David Shapiro’s first session of Civ Pro featured a discussion of Goldberg v. Kelly, a 1970 U.S. Supreme Court decision protecting the due process rights of welfare recipients. Richard Parker’s Crim Law and David Rosenberg’s Torts also started the semester without incident, but each morning Section III’s Contracts class met with Macneil, the room was riven with tension as the students waited to see whom he would call upon next. “If someone’s terrified, they’re not learning very well,” recounts Amy Christian, a magna cum laude 1988 graduate of Georgetown University who later became a law professor herself. She “couldn’t stand” Macneil’s classroom style, and most of her classmates soon felt likewise.

Making things worse, Macneil demanded that students initial an attendance roster each morning to demonstrate who was present. American Bar Association accreditation standards for law schools mandated that students actually attend most of their classes, but in 1988 the majority of law professors, at Harvard and elsewhere, paid little attention to this requirement. Macneil’s policy, followed by angry warnings when it was discovered that some people were signing in for absent classmates, roiled Section III even further. “People felt it was juvenile,” Lisa Hay, a 1985 summa cum laude Yale graduate, recalled. The practice was “really juvenile for a professional school,” agreed Martin Siegel, a 1988 highest honors graduate of the University of Texas.

“Relations between Macneil and the class broke down very severely very quickly,” Mark Kozlowski explained. In class Macneil came across as “a very angry person,” remembered Morris Ratner, who had just graduated with distinction from Stanford. The “toxic atmosphere” made the course “a disaster,” the exact same word that David Troutt, a biracial African American 1986 graduate of Stanford, used when recalling the day Macneil “cursed at me.” Aside from Macneil’s attendance policy, there was also the burden of “how demanding he was in terms of the volume of material that you had to cover and also because of how ruthless and unforgiving he was of people who weren’t prepared,” explained Paolo Di Rosa, a 1987 magna cum laude graduate of Harvard College. “He really humiliated people who weren’t prepared.” Michelle Jacobs came to believe that Macneil “liked humiliating people.” Jennifer Radding remembered the day Macneil called on her about secured transactions. “I’ll never forget it—obviously I’m still traumatized all these years later,” she joked equivocally. Greg Sater, like Ratner a 1988 Stanford graduate with distinction, felt Macneil was “really verbally abusive to people,” and Sarah Leah Whitson found him “so angry and critical and disparaging of students.” Di Rosa used the same adjective as Sater—“abusive”—to characterize Macneil, who was “just a monster,” and Di Rosa agreed with Amy Christian that the result was “more fear than respect.”

Rob Fisher was the only student who had spent six years at the front of a college classroom, but he fully shared his classmates’ view that Macneil was “a horrible professor” and Contracts “was the most painful course.” Fisher and Mark Kozlowski, also older, both quickly grasped that Macneil’s idiosyncratic approach was profoundly simplistic. “He had one idea,” Fisher recalled, “that contracts are relationships.” Kozlowski was even more dismissive, viewing Macneil’s focus as “a pointless effort to apply absolutely standard social science rhetoric to contracts.” Even worse, “he spent a lot of time on his theory and not a great deal of time on learning contracts,” which quickly led many in Section III to believe they were being shortchanged relative to friends in other sections. “There was a sense that Section III was not learning contracts at the same level as the other students and learning the doctrine,” recalled Tim Driscoll, a 1988 summa cum laude graduate of Hofstra University. “People just really thought that they were not learning contracts law, and they were getting cheated,” agreed Gina Torielli, an older student who had graduated from Michigan State with high honors.

Jackie Fuchs, a 1988 summa cum laude graduate of UCLA who before college played bass guitar alongside Joan Jett in the Runaways, agreed that Macneil was “very hard to get along with,” but she felt he simply “did not know how to relate to people in their twenties.” Kozlowski was less charitable. Not only was Macneil “extremely antagonistic in class,” he repeatedly “would simply insult people to their face,” and not just young women like Ali Rubin. Mark remembered a conservative white male politely saying he did not understand a question, yet Macneil responded, “It’s a point that would be obvious to any intelligent person. It’s not obvious to you.” Shannon Schmoyer, who had graduated summa cum laude and first in her 1987 class at the University of Oklahoma, summed up Section III’s view of Ian Macneil: “he was an embarrassment to Harvard Law School.”

Not all of Barack’s time and energy during the fall semester’s first weeks were devoted to his casebooks and class time. The law school’s Hemenway gym was indisputably a dump—a word that a dozen alumni used for the facility—but its convenient location made finding pickup basketball games easy, as long as yoga classes or volleyball matches were not taking place. Only a few hours after reassuring Ali Rubin how well she had coped with Macneil’s onslaught, Barack late that afternoon went to Hemenway and found a group that included twenty-two-year-old African American 1L Frank Harper, a magna cum laude graduate of Brown University, and four African American 2Ls: Kevin Little, Leon Bechet, Frank Cooper, and Kenny Smith. African American 1L David Hill, a 1986 high honors graduate of Wesleyan University, soon joined the regular late-afternoon mix.

When a student intramurals league got started shortly into the semester, a half-dozen of the black Hemenway regulars, including Barack, came together briefly on a team they called BOAM: Brothers on a Mission. “We weren’t very good,” remembered Kevin Little, perhaps HLS’s top basketball devotee. All during that 1L year, Barack spent a good deal of time on the basketball court, but “he didn’t want to hang out afterwards,” Leon Bechet recalled. “It seemed like he always had a schedule … like he had a mission and he had a purpose.”

With the 1991, 1990, and 1989 classes together, Harvard had more than 150 black law students on campus that fall, and the BLSA chapter seemed to have as much energy as their 1988 graduating class. BLSA scheduled its own orientation event for 1Ls soon after their arrival on campus. David Hill remembered how “Barack is holding court” and other new students “thought he was not a 1L” as they listened to him. “People were very surprised that this guy was a 1L simply because of how he was handling himself.” An evening or two earlier, standing in the checkout line at the Star Market in Porter Square, just up from the law school, Barack had introduced himself to an African American woman he recognized from the first day’s financial aid orientation session. “I think we’re both at Harvard,” he said to Cassandra “Sandy” Butts, a 1987 graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Butts was in Section I, but “we certainly bonded over some of our challenges in the financial aid office,” and she, like Rob Fisher, became a close friend of Barack’s in their first days at Harvard.

Butts was with Obama and David Hill at that BLSA gathering when 3L Sheryll Cashin approached. Cashin too recalled other students listening as Barack spoke. “Within a couple of minutes, all of the people around were just hanging on his every word.” Barack was “dressed kind of shabbily,” and “I remember him talking about community organizing.” Also listening was one of the youngest 1Ls, Christine Lee, a 1988 Oberlin College graduate who was still a few days shy of her twenty-first birthday. Lee had spent her early childhood in Paris, but when she was ten, her white mother left her alcoholic African American father and took her to live in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, where she grew up as the black daughter of a white single mother. From Christine’s youthful perspective, Barack sounded “kind of full of himself,” because “he acted like he’d come from a whole life of work in the trenches rather than just a little stint after college.” Barack “seemed pretentious,” and “I immediately did not like him.”

Barack remembered listening to and first meeting Derrick Bell at that BLSA orientation, but he was not immediately drawn to any of the five African American men on the law faculty. Even though Charles Ogletree was an untenured visiting professor, the 1978 Harvard Law graduate was an enthusiastic cheerleader for the school’s black law students, and by mid-September, Ogletree had begun convening the first of four fall semester “Saturday School” sessions during which he hoped to reassure black 1Ls that they should not allow self-doubts to prevent them from succeeding at Harvard Law School. Derrick Bell and David Wilkins joined Ogletree, as did Charles Nesson, a white 1963 summa cum laude Harvard Law graduate who had worked in the U.S. Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division before joining the Harvard faculty. Ogletree was at pains to stress that the Saturday-morning sessions were “not a remedial course,” and BLSA leaders, like Ogletree, used the gatherings to encourage black 1Ls to become active in and seek out leadership roles in a variety of student organizations. About forty students attended the initial meeting, and Obama’s black classmates remember that he rarely if ever attended “Saturday School.”

By mid-September, something else occurred in Barack’s life that he did not mention to any of his new law school friends. Sheila Jager was staying with him at his Somerville apartment. Her Fulbright fellowship was for her to spend twelve months doing her dissertation fieldwork at Seoul National University in South Korea. After Barack left for Harvard, Sheila had intended to leave Chicago in mid-September and go to Seoul. But Barack wrote to her soon after his arrival in Cambridge, and after some phone calls, Sheila agreed to fly to Boston before going to South Korea.

“Why did I end up with him for a month in his Somerville apartment before leaving for Korea?” Sheila asked herself after recounting how she had refused to accompany Barack to Harvard. “I never said that I wouldn’t visit him,” she remembered, and she also recalled how her parents, who were then in Japan, were “really angry with me” when they learned she was staying with Barack and would not arrive in Seoul until after they had left the Far East.

Barack and Sheila’s weeks together in the private basement apartment became a replay of their final months in Chicago before Barack’s trip to Europe and Kenya. “I felt smothered by Barack, by his neediness to be the center of my world, by his sheer overpowering presence, and by the isolation I felt because we were always alone,” Sheila recalled. Barack recounted what he most liked about his new life as a law student. “I do remember Barack telling me about Rob, although we never met. He described him, as I recall, as ‘a bear of a man’ and talked about him with great warmth, as a kind of older brother…. He said the two of them were the smartest people in their class at Harvard and ran rings around everybody else.” Many of Rob and Barack’s Section III colleagues were coming to share that characterization as the fall semester progressed, but after a month in Barack’s apartment, Sheila was indeed ready to leave for Korea.

“He was like a huge flame that sucked up all the oxygen, and toward the end of our relationship, I felt breathless, exhausted really. I remember getting off the plane in Seoul and feeling like I could breathe again.” Deep down, Sheila’s feelings for Barack remained the same as in Chicago. “I knew at that point that the relationship could not work in the long term even though I loved him very deeply. He, of course, realized this as well. When I left for Korea, I felt as if I had abandoned him, although the split was completely mutual.”

But even when Barack drove Sheila to Logan Airport, their relationship had not seen its true end.

As September turned to October for the 1L students in Section III, their distaste for Ian Macneil gave way to gallows humor as they realized they could do nothing to alter their fate. The section took on the mordant nickname of “the Gulag.” Lisa Hay, who had worked for Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis’s campaign before beginning her 1L year, began anonymously producing a weekly mimeographed newsletter chronicling life in Section III entitled Three Speech. It recorded odd or humorous statements from their reading and from classroom comments. Macneil, of course, was a prime target. One headline was: “You Make the Call: Fact? or Fiction?,” followed by a quotation from Macneil’s Contracts casebook: “Habit, custom and education develop a sense of obligation to preserve one’s credit rating not altogether different from that Victorian maidens felt respecting their virginity.”

Hay quoted Macneil’s maladroit attempts at classroom humor that often backfired. For example: “The sexual relation is a good one for you to think about—in the context of this course, I mean.” Or when Macneil asked, “Give me an example of a voluntary exchange,” Richard Cloobeck, one of Section III’s best provocateurs, volunteered, “Having sex with your girlfriend,” to which Macneil replied, “Give me an easier one.” The next week, when the concept of inadequacy arose, Macneil bluntly asked one student, “Does your girlfriend ever say you are inadequate?” and a few days later, he insultingly told another, “Maybe you don’t have the skills to be a law student.”

When Hay crafted a top-ten list of reasons for not doing Macneil’s assigned readings, entries included “slept through class,” “was laughing too hard at footnotes to read the text,” and a joke about Macneil’s almost daily references to the Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Most pointed of all was “Proportionality: Contracts homework out of proportion with length and value of class.” In October, Hay reported a joking exchange between two classmates: “ ‘If I learned I only had a week to live, I’d want to spend all my time with Macneil.’ ‘Why’s that?’ ‘Because he makes every minute seem like a year!’ ”

With the November presidential election, pitting Massachusetts governor Dukakis against the Republican nominee, Vice President George Bush, drawing near, Barack registered to vote on October 4. Starting the next day, he also began racking up a remarkable run of thirteen parking tickets over the next four weeks on his rusty yellow Toyota, with most of them happening on Mass Avenue just west of the law school. On campus, student politics were roiled when the conservative Federalist Society chapter objected to the student government’s reserving two committee seats for the Coalition for Diversity. Jesse Jackson addressed a pro-diversity rally of twelve hundred people, and Derrick Bell renewed his calls for greater minority representation on the law faculty.

David Shapiro’s Civ Pro course was Section III’s most vanilla class, but most students thought Shapiro was an excellent, witty teacher. Classmates and Shapiro recall Obama speaking only irregularly in Civ Pro, but they do remember him as one of the most talkative voices in Richard Parker’s Crim Law classroom. Parker had “a class discussion” style that stood in contrast to Macneil’s classic Socratic method, recalls Kenneth Mack, one of Section III’s other African American men. Mack thought Barack was a standout presence from the first week of class. “He was a striking figure,” Mack said. “He spoke very well, and very eloquently,” and seemed “older and wiser than the three years that separated our birth dates…. It seemed like I was twenty-four, and Barack was thirty-four,” like Rob Fisher. “He and Rob seemed like they were the same age.” Shannon Schmoyer agreed: Barack “just seemed so much more mature” than most other 1Ls.

Parker was an entertaining teacher, and having Peter Larrowe, a former police officer, in the class sometimes added a bracing dose of reality to discussions. Several students recalled Parker saying, “If you’re going to a protest, always take your toothbrush,” and Lisa Hay’s Three Speech recorded one exchange after Larrowe mentioned his background to Parker: “ ‘Does everyone know that you were a police officer?’ ‘They do now…. No more undercover work,’ ” Larrowe joked. Fisher also vividly remembered Parker querying students about their own experiences with police officers and one attractive woman describing how she was patted down outside a bar. “How did that make you feel?” Parker asked. “Oh, it was kind of nice,” she replied as the entire class erupted in laughter.

Sarah Leah Whitson remembered Obama once making some real-world rather than doctrinal point in a colloquy with Parker, and Richard Cloobeck recalled a similar scene where Barack “spoke from the black perspective in Crim class because something had happened to him where he’d experienced racial discrimination in profiling, and it was very personal.” Sherry Colb, valedictorian of Columbia’s 1988 graduating class and Section III’s most loquacious female voice, remembered that when the subject of acquaintance rape came up in class, Barack expressed displeasure with what others had said. “ ‘I don’t even understand why we’re debating this. Why is silence enough? Why aren’t people looking for “yes”?’ ” Sherry recalled Barack asking. “I think the women in the class really appreciated that because there were other males in the class who took a more reactionary position.”

Sima Sarrafan, an Iranian American honors graduate of Vassar College, realized that Obama “had a more pragmatic view of the law” than most classmates or professors. Roger Boord, a 1988 magna cum laude graduate of the University of Virginia, remembered Barack as “this voice of authority … his voice was like Walter Cronkite.” But especially in Parker’s class, Barack, David Troutt, and Sherry Colb spoke up so regularly that it generated irritation and derision from some fellow students. Most Section III students spoke only when asked to. “The last thing I ever wanted would be to be called upon,” Greg Sater explained. “Most of my friends were the same way, and we would never in a million years ever raise our hand.”

In stark contrast, Section III’s most self-confident voices, or “gunners,” in longtime law student parlance, raised their hands almost every day in participatory classes like Richard Parker’s. Dozens of Obama’s classmates remember him consistently waiting until a discussion’s latter part before he chimed in, with comments that he thought synthesized what others had said. “He never really took a very strong, argumentative position,” Ali Rubin recalled. Dozens laughingly recalled his insistent usage of the word “folks” as well as his regular introductory refrain of “It’s my sense” or “My sense is,” phrases that DCP members remembered hearing regularly during his time in Chicago. Barack “particularly loved to engage with Professor Parker,” Haverford College graduate Lisa Paget recalled. She has a “vivid” memory of Barack remarking, “Professor Parker, I think what the folks here are trying to say is” so as “to synthesize what other people were saying.” Barack “clearly liked to speak,” but “sometimes people got frustrated because they didn’t feel like they needed him” to speak for them. “ ‘Say what your own thinking is, don’t tell him what we’re thinking!’ ”

Decades later, particularly for classmates who had become jurists or prominent attorneys, recollections of just how intensely irritating Obama’s classroom performance had been were burnished with good humor. But even though he was always prepared, always articulate, and always on target, many fellow students tired of Obama’s need to orate. Barack “spoke in complete paragraphs,” Jennifer Radding recalled, but “he often got hissed by us because sometimes we would all make comments” and then “he would raise his hand and say ‘I think what my colleagues are trying to say if I might sum up,’ and we’d be like ‘We can speak for ourselves—shut the fuck up!’ ” Radding thought Obama was “a formal person, reserved” but “always friendly.” Yet “I’m not sure he related to women as well on a colleague basis” as he did with older male friends like Rob, Mark Kozlowski, and Dan Rabinovitz, a former community organizer interested in politics. Jennifer remembered Barack asking Rob and Dan substantive questions, and “then he’d ask me did I party over the weekend.” One day “I called him on it, and I just said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. You’re someone who’s so liberal, and so women’s rights, and you talk to women like they’re not on the same level.’ It horrified him to hear that,” and “I wasn’t the only one who felt this way.”

The joking about Obama’s classroom performance intensified as the fall semester progressed. One classmate, Jerry Sorkin, christened him “The Great Obama” because “he had kind of a superior attitude,” Sorkin’s friend David Attisani remembered. “Barack would start a lot of his speeches with the words ‘My sense is,’ and Jerry would walk around kind of stroking his chin saying ‘My sense is.’ ” Gina Torielli recalled that when Obama or especially Sherry Colb raised their hands to speak, more than a few of the younger men would “take out their watches to start timing how long” they talked. In time it became a competitive game, one played at many law schools over multiple generations, and often called “turkey bingo,” in which irritated classmates wager a few dollars on how long different gunners would exchange comments with the professor. Section III named its contest “The Obamanometer,” Greg Sater recalled, for it measured “how long he could talk.” But Sater explained how there “was a great feeling of relief to all of us whenever he would raise his hand because that would take time off the clock and would lower the chances of us being called upon.”

No one questioned the value of what Barack, Sherry, or David Troutt had to say, but much of Section III got tired of hearing the same voices day after day. With Barack, Greg said, “we were envious of him in many ways because of his intellect,” self-confidence, and poise, but that did not stop the Obamanometer. “We’d kind of look at each other and tap our watch,” he recalled. “You might raise five fingers,” predicting that long a disquisition, “and then your buddy might raise seven.” Jackie Fuchs remembered the label a little differently, explaining that students would “judge how pretentious someone’s remarks are in class by how high they rank on the Obamanometer.”

Criminal Law was the course in which Barack “pontificated”—as Jackie called it—the most, but the class and professor that Barack and Rob found the most intellectually stimulating was Torts, with David Rosenberg. With only one-third of Section III’s students in that subsection, it was more intimate than Contracts, Civ Pro, or Crim, and the forty-five students responded enthusiastically to Rosenberg’s high-energy, in-your-face style and tough-minded libertarian economics. Everyone remembered Rosenberg’s invitation to a 6:30 A.M. law library tour, when he would discuss the practicalities of thorough legal research. Amy Christian, Richard Cloobeck, Diana Derycz, and Barack were among the half dozen or so students who showed up, and Three Speech recounted Rosenberg insisting during it, “I am not a masochist.”

David Attisani “loved” Rosenberg’s class. “He was my most useful professor by a wide margin,” and Rosenberg also held a volleyball clinic and took a large group of students out to dinner. Richard Cloobeck agreed that Rosenberg was “the most practical and realistic and effective” of Section III’s professors. He also was often the most entertaining. Mark Kozlowski remembered Rosenberg asserting that Harvard-trained lawyers taking legal-services jobs was the equivalent of MIT engineering graduates becoming appliance repairmen. Three Speech captured an exchange in which one student asked Rosenberg if a passage in one case opinion was dicta, or beside the point; Rosenberg responded, “No! That’s crap!”

Kozlowski and Cloobeck remembered how captivated Fisher and Obama were with Rosenberg, and Ali Rubin thought that “from the beginning Rosenberg treated Rob and Barack differently” than other students. Cloobeck believed Obama spoke just as much in Torts as he did in Crim, demonstrating to all how “incredibly, intensely smart and thoughtful” he was, even relative to classmates who had graduated at the top of their classes from the nation’s best colleges and universities. Obama was “intellectually curious” and “sincere in his academic passion,” Cloobeck thought, but he also seemed “extremely arrogant, very conceited.” Yet he admitted that Barack and Rob spoke “at a level that was just beyond my comprehension.”

David Rosenberg remembered Barack as “one of the most serious students I’ve ever encountered.” Rosenberg’s approach to Torts involved “applying social and natural science to social problems” in a heavily economic, functionalist manner. He recalls that “Obama and Fisher were determined to figure out what was going on, absolutely determined.” The two came by his office “almost twice or three times a week, not to talk about the course in ways that would translate into a better grade, but to talk about the actual problems that I was raising and the approach.” Rob and Barack were always together—“you couldn’t separate them,” Rosenberg explains—but “they weren’t a duo in their mind-sets,” and “it didn’t seem like one was dependent on the other. They were quite independent,” and always raising “social policy questions” when they came by. Rosenberg remembered that in class, Obama “asked good questions, he fought through hard problems. I thought he was going to be a top academic.”

Rob remembered that “Barack was very active” in Torts and “loved that class.” Rosenberg “met argument with argument, and valued creativity,” and “Barack and I just had a great time in that class. We were constantly arguing and talking and enjoying it and going to visit Rosenberg,” and Torts overall was “an absolute blast.” Rosenberg “had this intense intellectual passion” and a “creative style of lawyering that greatly appealed to us both.” Rob believes that “Rosenberg had a vastly bigger influence on Barack’s and my thinking about law” than their other 1L instructors combined.

Four years earlier, Rosenberg had published a major article in the Harvard Law Review calling for a restructuring of tort litigation in mass exposure cases like asbestos through the courts’ use of “aggregative procedural and remedial techniques,” an argument he revisited in a shorter 1986 HLR essay. In fall 1988, Rosenberg was writing an additional commentary, calling for “collective processing” and comprehensive settlements in mass tort cases rather than “legislative insurance schemes.” He was already so impressed by Rob and Barack that he sought their input on his draft manuscript. When it was published in May 1989, the first page included thanks to Rob and Barack for their “substantive criticism and editorial advice,” a remarkable acknowledgment for a Harvard law professor to bestow upon two 1L students.

Amy Christian remembered a day in Torts when “one of Barack’s two front teeth was broken diagonally so that like half the tooth was gone,” a casualty from the previous afternoon’s basketball game, he told her. “A couple of classes later he came in, and his tooth looked totally normal.” Kenny Smith, a 2L, remembered Barack as “a good player,” but two recollections of Obama from among the wider population of classmates who went up against him either in intramural matchups or the almost daily pickup games were his penchant for “trash talk” insults to opposing players and his tendency to call “baby” fouls in self-refereed games. Barack “was cocky as a basketball player, he was not as a regular person,” 1L Brad Wiegmann thought. Martin Siegel recalled “being in a game with him where he called a foul” and “he just headed to the other end of the court.” Oftentimes, “being a law school, if people called fouls there was a tendency to have that devolve into a crazy argument.” Not so with Obama. In “a sign of his status,” everyone “followed him without objection. It was as if he had said it, and therefore it was so.”

Greg Sater had formed a volleyball league, and their court time was just after basketball, but the basketball players would refuse to give up the floor. “They would always give me shit,” Sater recalled, and then Barack would “sweet-talk me into giving them an extra few minutes, always.” He was “very disarming” and “very good at defusing situations and being a peacemaker.” Rob Fisher had similar memories from pickup basketball games, but they spent far more time studying than on the basketball court.

The press of coursework led Barack to give up on the irregular journal he had kept ever since his first year in New York, and he and Rob often studied at his Somerville apartment rather than in Harvard’s law library. Rob remembers that Barack was very proud of “three Filipino gun cases,” big long wooden boxes he had bought to serve as bookshelves, but otherwise the “apartment was very sparse,” with “a little TV,” some “spare furniture,” and overall an “ascetic” feeling. “He and I would sit around his apartment,” Rob recalled, “and just bang ideas back and forth for hours.”