По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

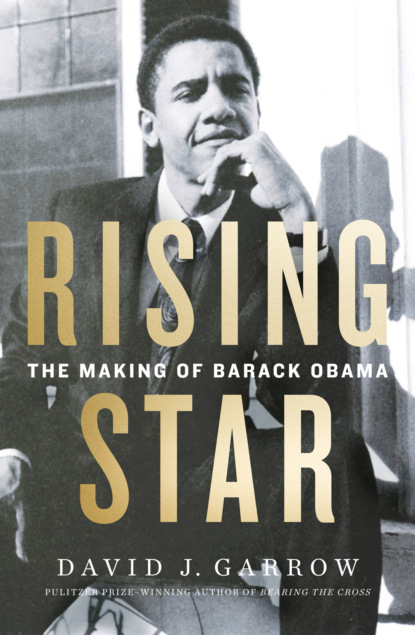

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Before the summer ended, Hazel Johnson and Marian Byrnes staged three more protests near the CID entrance, taking care not to get arrested. They also testified before the special joint legislative committee, chaired by Emil Jones. Assisting Hazel was a thirty-five-year-old black man who had just returned to Chicago after working toward a master’s degree at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and who had earlier won a Rhodes Scholarship to attend Oxford University in England. Like Jones, Melvin J. “Mel” Reynolds was eyeing a challenge against incumbent U.S. congressman Gus Savage in the spring 1988 Democratic primary, and both men—like Savage—were eager to raise their profiles among district residents angry over authorities’ inability to take meaningful action against the Southeast Side’s multiple toxic threats.

Several months earlier, Harold Washington had elevated Howard Stanback to an influential post as his assistant in charge of the city’s infrastructure. An African American economist, Stanback had taught at New York’s New School for Social Research until he came to Chicago as Maria Cerda’s deputy at MOET. His new appointment made him the mayor’s primary adviser on Chicago’s landfill crisis, and in late summer 1987, Stanback gave Washington a memo that laid out the city’s options. Chicago had done “very little towards developing and implementing alternatives to dumping,” making the city almost completely dependent on landfill availability. The only solution was “the O’Brien Locks property currently owned by the Metropolitan Sanitary District,” but using that property would mean lifting the moratorium and incurring a huge uproar from Southeast Chicago.

Stanback gave the mayor two options for how to proceed. One would be to convey the land to WMI, to whom “the site is probably worth $1 billion,” and in order “to neutralize opposition to lifting the moratorium,” WMI would contribute sufficient funds to the surrounding neighborhoods, just as Mary Ryan’s outreach efforts envisioned. Stanback believed that this could succeed, even with WMI’s “negative image,” and that this was superior to the second option, which would involve the city itself operating a landfill on the O’Brien Locks property. Stanback believed political opposition would be higher to this scenario because it would not include WMI’s contributing to community revitalization projects. “Operating a landfill is not a business the City should enter,” Stanback recommended.

One Saturday, Stanback drove to South Chicago to meet Bruce Orenstein at UNO’s East 91st Street office. Also there that morning was DCP’s Barack Obama, whom Bruce had asked to join them. Stanback described the city’s thinking regarding the landfill and WMI’s proposal, but he also explained that Washington wanted to be sure that WMI’s big gift would not be controlled by the Southeast Side’s traditional power brokers, particularly South Chicago Savings Bank president James A. Fitch, a longtime backer of mayoral rival Ed Vrdolyak and the dominant figure in the four-year-old Southeast Chicago Development Commission (SEDCOM). If a deal could be cut with WMI, the mayor wanted his allies—such as UNO, with whom Washington had worked in close alliance for four years—to take charge of the windfall.

“Barack in particular, his eyes got so bright,” Stanback remembered. “He said, ‘This can be one of the biggest community development coups of all time.’ I said, ‘You’re right,’ ” but UNO at present had no development capacity. “We agreed that nothing was going to happen anytime soon,” Stanback recalled, but “we agreed in principle” that UNO, DCP, and the city would closely coordinate as discussions moved forward. When Fitch then wrote to another Washington aide, budget director Sharon Gist Gilliam, to initiate a discussion of lifting the moratorium to allow for WMI’s use of the O’Brien parcel, Gilliam waited twelve days before sending Fitch a cold, rude reply stating that she had given his letter to Stanback.

For Obama, the late summer of 1987 was a busy and intense time. Throughout July, his hourly consultations with Greg Galluzzo were more than weekly, but from August forward the two men met only twice monthly, as Greg began having ninety-minute or longer sessions with Johnnie Owens almost weekly. One weekend, Barack met Ann and Maya in New York, where Maya was looking at Barnard College and Ann was visiting friends before returning to Pakistan via London. A rooftop photograph shows Ann and Barack with several of her anthropologist friends, including Tim Jessup, who had first met Barack in Jakarta four years earlier and had seen him again in Brooklyn in 1985 with Genevieve. Barack stayed with Hasan and Raazia Chandoo in Brooklyn Heights, playing basketball nearby with Hasan and walking across the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan.

Hasan recalled that “by that time he knows for sure he wants to be a political person,” and Beenu Mahmood, then a lawyer in Sidley & Austin’s New York office, remembered the visit similarly. “By that time he was very clear that he was going into politics” and “it was very clear that law would be the vehicle for getting into politics for him.” Several nights Raazia cooked dinner, but one thing had most definitely changed: by 1987 Barack never again “partied” as he had so many times in 1984 and 1985. Hasan recalled Barack mentioning how brutally cold Chicago winters were and also remembers him describing the time he and Johnnie had to duck behind a car when they heard gunfire nearby in Palmer Park. Raazia, five years younger, found “Barack a little bit arrogant”—just “intellectually arrogant,” Hasan interjected—“so I didn’t want much to do with him.”

Obama was back in Chicago by the end of the second week in August, and he may or may not have seen a prominent headline in the Defender that would have reminded him of an influential relationship from earlier in his life: “Frank Davis Dead at 81.” During Sheila’s midsummer visit home, she told her mother much of what Barack had said to her in recent months, and Shinko Jager in turn recounted Sheila’s comments to Mike Dees, the family’s closest friend, who had met Barack months earlier during the Christmas holiday. Barack’s marriage proposal still loomed, and “if Sheila went with Barack, she would have to follow his lead. He wanted to be president.” Shinko remained opposed to the marriage, “but she never gave a reason,” Mike recounted. “I was against it because I thought they were two ambitious people, and I knew they wanted their own separate careers, and he was talking about being president, which I thought was a little strange” for a twenty-five-year-old community organizer. But there was also something more, something Barack had begun to articulate to Sheila. “There was a problem there,” Mike recalled. “He was concerned if he was going to take the steps to the presidency with a white wife.”

One August Friday, Sheila joined Barack for the trip to Asif’s summer house in Madison. Sheila was “very quiet” and slept in the back of the car most of the drive, but an unusual tension was present. By Saturday morning, the problem broke into the open, and Barack and Sheila kept pretty much to themselves upstairs. But according to someone there that weekend, “it’s the summer … these houses are old. You’d die if you closed windows. Everything is open.” From morning onward “they went back and forth, having sex, screaming yelling, having sex, screaming yelling.” It continued all day. “That whole afternoon they went back and forth between having sex and fighting.”

Others remember “moving around to the other side of the porch just to be able to talk.” It “was a long weekend” and “an incredibly unpleasant one,” one person recalled. “It was so stressed and tense.” Barack tried “to be more social about it,” and “they came down a few times to grab a beer, to eat,” but “then they went back up to scream or fight.” Sheila was “a very sweet person … very mild-mannered,” and “certainly exotic” in her looks, but “shy and withdrawn” that “extremely emotional” weekend.

“They called truces here and there, but it kept popping back up” that Saturday afternoon, as “she screamed and they fought.” Sheila’s voice came through loud and clear: “That’s wrong! That’s wrong! That’s not a reason,” she was heard saying. As the others talked quietly, the explanation of what they were hearing was shared: Barack’s political destiny meant that he and Sheila could not have a long-term future together, no matter how deeply they loved each other. But she refused to accept his rationale: “the fact that it was her race.” It was clear—audibly clear—that “she was unbelievably in love with him,” that “the sex for her was the way to bring it back.” Barack “was very drawn to her, they were very close,” yet he felt trapped between the woman he loved and the destiny he knew was his. According to one friend, Barack “wasn’t black enough to pull that off and to rise up” with a white wife.

Sunday afternoon Barack drove them south to Chicago, with Sheila again napping in the back seat. “Thank god it’s a crappy car that made a lot of noise!” A quarter century later, Sheila had almost no recollection of going with Barack to Madison, but she unhesitatingly characterized their relationship as “a very tumultuous love affair.” No matter how others saw Obama, “the Barack I knew was not emotionally detached, in control, and cool,” she stressed. Instead, Barack was “a very passionate, sentimental” and “deeply emotional person,” indeed “the most overwhelmingly passionate and caring person I ever knew.”

In Barack’s workday world, Cathy Askew, the white single mother of two half-black daughters, witnessed most starkly Barack’s newly articulated racial identity. With a new school year about to begin, Cathy told Barack about what she considered a perplexing and offensive racial conundrum: although the Chicago Board of Health said her daughters were black, their school in West Pullman wanted to count them as white. Cathy rejected this binary view of racial identity—“50-50 is a good term”—and expected biracial Barack to agree. She was astounded when he rejected any middle ground, especially since he had spent most of his childhood in a predominantly “hapa” world. But he did. “He said, ‘Well, there comes a time when you have to pick a side, you have to choose a side,’ ” Cathy remembered him saying. And Barack repeated it: “You have to choose.”

More than a decade later, Barack again gave voice to the sentiment he had expressed to Cathy. “For persons of mixed race to spend a lot of time insisting on their mixed race status touches on a fear” that a darker complexion is innately inferior to a lighter one, and too many nonwhite people are “color-struck…. There’s a history among African Americans … that somehow if you’re whitened a little bit that somehow makes you better, and that’s always been a distasteful notion to me,” perhaps ever since seeing that magazine story one day in Jakarta. “To me, defining myself as African American already acknowledges my hybrid status,” and “I don’t have to go around advertising that I’m of mixed race to acknowledge those aspects of myself that are European … they’re already self-apparent, and they’re in the definition of me being a black American.” Any other mind-set intimated racism. “I’m suspicious of … attitudes that would deny our blackness.”

Fred Hess knew well ahead of time that September 1987 would witness a train wreck of historic proportions for Chicago Public Schools. The board of education needed to negotiate new contracts with multiple unions, most important the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU), and in midsummer, Hess had told the board that it could afford to offer a pay increase of 3.5 percent to teachers. Instead, the board announced a three-day reduction in the upcoming school year, thereby cutting teachers’ pay by 1.7 percent. The CTU demanded a 10 percent salary increase, and Superintendent Manford Byrd asserted that CPS could afford no raise at all. Hess labeled that claim “a bunch of bull,” and on September 4, four days before schools were to open, more than 90 percent of CTU members voted to strike.

The strike began on September 8, with Hess warning the Sun-Times that “it’s going to be a long strike because it looks like it has turned into a question of principle,” especially for Byrd. In a subsequent op-ed in the Tribune, Hess denounced “an administration that insists on adding central office administrators while cutting other employees’ salaries.” More than 430,000 students were out of school, and on September 11 a large group of parents and students from sixteen community groups picketed CPS headquarters, with the group’s spokesman, Sokoni Karanja, telling the news media that “our children are victims of a school system that is failing to educate them.”

Karanja was a forty-seven-year-old African American native of Topeka, Kansas, who had earned a Ph.D. from Brandeis University in 1971 before moving to Chicago’s historic Bronzeville neighborhood, joining Trinity UCC, and founding a family-aid organization he christened the Centers for New Horizons. Nine months earlier, Karanja had become the Woods Fund’s first black board member, but this September 11 was significant because it illuminated the deepest social and political chasm in black Chicago: African American families with children in heavily minority public schools were fighting against a system made up of 41.6 percent black administrators and 47 percent black teachers.

Those numbers explained why Harold Washington had been so ambivalent four months earlier when he seemingly embraced school reform. The city’s public schools provided middle-class salaries and middle-class status to thousands of black Chicago families, while at the same time they were shortchanging tens of thousands of black students. The human toll was staggering: more than 40 percent of African American men in Chicago in their early twenties and 35 percent of young African American women were unemployed, many of them lacking basic job skills because the CPS had not offered them real schooling.

“Our education system is in shambles,” Rob Mier, Washington’s economic development commissioner, publicly acknowledged. “We’re producing a legion of functional illiterates.” Some critics described “a vicious circle of incompetence,” with CPS hiring teachers who had graduated from weak nearby state universities, which enrolled mainly ill-prepared graduates of Chicago high schools. As Fred Hess kept emphasizing, the abysmal state of public education in Chicago was the result not of a lack of resources, but instead of their dramatic misallocation: during the 1980s, “the number of central office administrators rose by 29 percent while the number of staff members in the schools rose by 2 percent.” By 1987, CPS’s central bureaucracy had reached an astonishing thirteen thousand employees.

On Thursday, September 17, two hundred angry parents picketed outside Harold Washington’s Hyde Park apartment building while others targeted the homes of Governor Jim Thompson, new board of education president Frank Gardner, and CTU president Jacqueline Vaughn. The next morning more than a thousand parents and children picketed outside CPS headquarters, but as the strike moved into its third week, neither the board nor the union were showing any signs of compromise. Superintendent Manford Byrd, furious at Fred Hess’s disparagement of CPS’s central administration, wrote his own op-ed for the Tribune, claiming that the system’s fundamental problem was “the extraordinary special needs of most Chicago public school students.”

That remarkable assertion—a school superintendent labeling the majority of his system’s children as “special needs” students—laid bare the deep class divide within black Chicago between middle-class professionals and “those people.” As Hess later explained, again echoing John McKnight’s analysis, Byrd’s explicit articulation of a “deficit model of ‘at-risk’ ” children revealed the attitudes of administrators “whose jobs depend on the existence of a pool of ‘at-risk’ students as clients.” Unable to see that students might bring strengths to school, CPS bureaucrats could not imagine that Chicago’s schools, “rather than the students themselves, might be to blame for students’ lack of success,” Hess explained. Only by reallocating power from CPS headquarters to local schools so as to “reemphasize local communities rather than large, hierarchical bureaucracies” could meaningful educational improvement be attained.

While most parents and community groups were angry with the CTU as well as the board, UNO simply backed the teachers’ demands. As the strike entered its third week, the parents’ groups, with support from Anne Hallett at Wieboldt and input from Al Raby, came together as the People’s Coalition for Educational Reform (PCER). On Thursday, October 1, in what the Tribune called a “dramatic confrontation,” a predominantly black group of PCER representatives, many of whom were close allies of Harold Washington, told both the board and the CTU that a 3 percent raise must be agreed upon to end the strike. First the board, overruling Byrd, and then a reluctant CTU, bowed to the coalition’s demand, and on Saturday morning it was announced that schools would reopen on Monday. Nineteen days of classroom time had been lost in “the longest public employee strike in Illinois history.”

On Sunday, Harold Washington summoned Casey Banas, the Tribune’s education reporter, to his Hyde Park home. The mayor wanted everyone to know he understood the significance of the parents’ protests. “Never have I seen such tremendous anger and never have I seen a stronger commitment on the part of people” to make Chicago a better city. But Washington also did not want to alienate the black educators Manford Byrd represented. “There’s no discipline in many homes. There’s no stimulus in many homes. And even though the educational structure is a poor substitute to supply what the family is not supplying, it must be done,” the mayor declared. He said he would personally lead a new, far more inclusive iteration of his Education Summit to reform Chicago’s public schools. It would begin the next Sunday at the University of Illinois’s Chicago Circle campus (UICC). “We’re going to have a massive forum,” Washington promised.

Obama and DCP had remained entirely on the sidelines throughout the protests against the shutdown. On the Monday of the strike’s final week, and after three months of trying, Barack finally had an appointment with Harold Washington’s top policy adviser, Hal Baron, to pitch his Career Education Network plan to the mayor. It was entirely thanks to John McKnight that Baron consented to see Obama, despite education aide and Roseland native Joe Washington’s negative attitude. “I did it purely as a favor to John McKnight,” Baron recalled. “John was just so high on him…. I think John wanted me to get him a meeting with the mayor, but he pestered me and I finally did a meeting with him myself.” Joe Washington joined Baron in Hal’s City Hall office, but Barack’s presentation was anything but persuasive. Baron remembers it as “cocky standard Alinsky bullshit” and “very glib.” He also recalls Obama saying, “ ‘We’ve got Roseland organized.’ ” After Barack left empty-handed, Joe Washington told Baron what he thought: “That guy doesn’t know shit about Roseland.”

Far more fruitful for Obama was his relationship with John McKnight. Barack’s reactions to now two years of immersion in the macho, conflict-seeking world of Alinskyite organizing—including his first year with Jerry Kellman, dozens of hours with Greg Galluzzo, and his warm, almost brotherly relationship with fifteen-years-older Mike Kruglik—had drawn him toward McKnight’s alternative vision of human communities. At least twice Barack drove up to McKnight’s second home in Spring Green, Wisconsin, west of Madison, for weekend-long discussions. He was the only young organizer other than Bob Moriarty with whom McKnight had developed a truly personal relationship, and one weekend Barack brought Sheila along with him. Jerry, Greg, Johnnie, Mary Bernstein, Bruce Orenstein, and Linda Randle would all remember meeting Sheila a time or two, usually by chance in Hyde Park or at her and Barack’s apartment on South Harper. “She’s a cutie,” Bruce remembered, but virtually never did Barack seek for anyone in his workday world to meet or know the woman with whom he lived. Mike Kruglik never laid eyes on her.

But one Friday Barack drove north with Sheila, and McKnight remembered Barack calling him from the Penguin, a working-class bar in nearby Sauk City, to say that his shabby Honda had broken down. John drove in to pick them up, and Barack introduced him to Sheila, whom McKnight thought was “absolutely stunning.” The regulars at the Penguin “must have been pretty surprised when that couple walked in,” McKnight suggested.

That weekend, like others, was spent mostly “talking about ideas,” McKnight recounted. Barack had a “set of things he was concerned about that he didn’t think he could talk with Kellman or Greg about that was outside the true faith.” McKnight, as a longtime Gamaliel board member, knew how “absolutely rigid” Greg was about the Alinsky model’s view that the way to make people “feel powerful was their anger,” instead of feeling “powerful because of their contributions.” Barack was deeply averse to anger and confrontation, and therein lay his difficulty with the attitude that Alinsky organizing sought to inculcate in its young initiates. McKnight remembered these discussions were “mostly my … responding to him about questions he had,” with McKnight talking about how his asset orientation differed from the “really true faith people” like Greg. McKnight had just written a powerful new paper, “The Future of Low-Income Neighborhoods and the People Who Reside There,” addressing what he termed “client neighborhoods.” Anyone who had spent time in Altgeld Gardens would have appreciated McKnight’s analysis. Such areas are “places of residence for people who are not a part of the productive process” and “have no hopeful future.” What was needed was “a new vision of neighborhood that focuses every available resource upon production.” In a sentence that reached directly back to the quintessential lesson of the 1960s’ southern freedom movement, McKnight insisted that for a group like DCP, “it is the identification of leadership capacities in every citizen that is the basis for effective community organization.”

As McKnight and Obama continued to talk throughout 1987, what became “very clear to me was that I was talking to a young man who had not bought the true faith,” McKnight remembered, one who had come to realize that Alinskyism “is ultimately parochial” and offered no prospects whatsoever for attaining large-scale social change. As the best historian of Chicago racism, Beryl Satter, would incisively note, Alinskyism’s “insistence on fighting only for winnable ends guaranteed that” community organizing “would never truly confront the powerful forces devastating racially changing and black neighborhoods.”

McKnight’s long-term impact on Obama would be profound, irrespective of how much Barack later remembered of their conversations or how few commentators were knowledgeable enough to hear the readily detectable echos. “If you want to see an intellectual influence on Obama’s thinking, it’s John McKnight,” citizenship scholar Harry Boyte told one Washington audience two decades later. “A lot of things started in part through John McKnight,” observed Harvey Lyon, a Gamaliel board colleague whose political roots also reached back to the 1960s. Stanley Hallett, an influential urban development pioneer, a onetime theology school classmate of Martin Luther King Jr., and the husband of Wieboldt’s Anne Hallett, was also deeply influenced by McKnight. For Hallett, directing public funds to service poor people’s professionally identified needs is “money spent to maintain people in a condition of dependency,” Hallett told one interviewer. Progressive public officials needed to stop “looking at people in terms of their problems instead of their capabilities.”

The People’s Coalition for Educational Reform issued its demands in advance of the mayor’s Sunday, October 11, summit. Calling for local school-based management, greater parental involvement in schools, a requirement that 80 percent of students perform at or above grade-level standards, and deep cuts in CPS’s huge central bureaucracy, PCER made clear its student-centered focus: “We do not want cuts to affect anyone providing direct service to students.” On Sunday, almost a thousand people packed UICC’s Pavilion as the mayor slowly made his way through the crowd. The Tribune described the almost four-hour program as having a “town-meeting atmosphere,” and called it “the most remarkable gathering to focus on the Chicago public schools in at least 25 years.” Washington proclaimed that “a thorough and complete overhaul of the system is necessary,” promised to appoint a fifty-member parent/community advisory council within two weeks, and pledged to present a unified reform plan within four months.

Washington soon convened the first meeting of his Parent Community Council, promising it would begin holding neighborhood forums before the end of November. The city’s most influential biracial coalition of business leaders, Chicago United, also shared its own school reform plan with the Tribune. Angry at Manford Byrd for his arrogance and disinterest in meaningful change, Chicago United had adopted the belief of Fred Hess and Don Moore that the best path toward improved student performance was through parental and community control of local schools. Patrick J. Keleher Jr., Chicago United’s public policy director, said, “we think the leadership could be found” and that organizations such as UNO could recruit and train interested parents.

At the same time, Barack’s DCP work remained often frustrating. Some Saturday mornings he met with the Congregation Involvement Committee at Rev. Rick Williams’s biracial Pullman Christian Reformed Church, while he and Johnnie Owens also met with two Chicago State University (CSU) professors who had just started a Neighborhood Assistance Center. The only result of that was Barack being invited to join a CSU-sponsored panel at a mid-October conference on “Developing Illinois’ Economy.” One of his fellow panelists, CSU’s Mark Bouman, addressed “the spectacular fall of big steel,” and another speaker was Chicago Tribune business editor Richard Longworth, who had written so forcefully about Frank Lumpkin’s efforts on behalf of Wisconsin Steel’s former workers. Whatever Barack contributed to the session was unmemorable, for Longworth, looking two decades later at a photograph of himself and Obama sitting side by side, had no recollection of the event whatsoever.

In Roseland, significant economic development news came from the low-profile Chicago Roseland Coalition for Community Control (CRCCC), a twelve-year-old organization that had successfully followed through on the interdenominational protests against Beverly Bank that Alonzo Pruitt and Al Sampson had mounted seven months earlier. When the bank announced plans to open a new branch in suburban Oak Lawn, the little-known Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977 allowed CRCCC to petition the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC) to block that expansion. Three years earlier Beverly Bank had stopped making home mortgage loans, leaving it vulnerable to FDIC enforcement of the CRA’s community service requirements that proscribed disinvestment in older neighborhoods. Advising and guiding CRCCC’s strategy was the similarly low-profile Woodstock Institute, a nonprofit fair-lending organization created in 1973 by five founders, three of whom were John McKnight, Al Raby, and Stan Hallett. Woodstock vice president Josh Hoyt, an organizer who previously had worked under Greg Galluzzo and Mary Gonzales at UNO’s Back of the Yards and Pilsen affiliates, brought the Beverly situation to the attention of U.S. Senate Banking Committee chairman William Proxmire’s staff, and Proxmire wrote to FDIC chairman William Seidman. Soon Beverly Bank was in negotiations with CRCCC president Willie Lomax, and the national American Banker publicized the tussle. By mid-September Beverly had agreed to commit $20 million worth of loans to low-income Far South Side neighborhoods over the next four years and to open central Roseland’s first ATM. “We made use of some tools of the law to get the bank here,” the courageous Lomax told the weekly Chicago Reader’s excellent political reporter Ben Joravsky. “We had to play hardball.”

The “tools of the law” were increasingly on Barack’s mind by October 1987. Going to law school had been a possibility for years, ever since his graduation from Columbia. His grandmother more than once had spoken of a career in law and then a judgeship, and Barack had never seen his work as a community organizer as something long term. He had mentioned going to law school in passing to several people in recent years—IAF’s Arnie Graf being one—and early in 1987 Barack had heard a National Public Radio interview with Supreme Court justice William J. Brennan Jr. Brennan told NPR’s Nina Totenberg that the guarantees in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights are “there to protect all of us” and to “protect the minority from being overwhelmed by the majority.” Barack would later recall what he termed “the wisdom and conviction” of Brennan’s words.

Barack’s embrace of his “destiny,” as he described it to Sheila, had quickened his thinking for the last six months. Kellman’s move to Gary had left DCP entirely in Barack’s hands until he had been able to hire Johnnie Owens, but once Johnnie was on board, Barack’s references to law school—to Sheila, to his close friend Asif Agha, to Asif’s friend Doug Glick on their long drives up to Madison and back—became far more frequent. Early that fall Bobby Titcomb, Barack’s closest Hawaii friend, passed through Chicago, and he remembers Barack talking then about wanting to get a law degree. Asif left Chicago in early November for six months in Nepal, and one October evening, not long before he left, he went to Barack and Sheila’s apartment on South Harper. “We used to cook dinner for each other a lot,” said Asif, and that evening Barack was out on one of his several-days-a-week runs along Hyde Park’s lakeshore. “I was sitting with Sheila in the kitchen, and he walked in all sweaty,” wearing shorts, and “I remember him saying something about his law school essay, and that he had been mulling it over for many days, maybe weeks.” Mary Bernstein remembered Barack mentioning it to her as well. He had cited Harvard in particular to Asif—“his dad went to Harvard,” Asif remembered, “so he had some interest in Harvard” and “that was his first choice.” Asif had not heard what Barack had told Sheila about a “destiny,” but after two years of weekly conversations, he knew Barack “was an ambitious person.”

Several weeks earlier, Jerry Kellman told Obama about a conference titled “The Disadvantaged Among the Disadvantaged: Responsibility of the Black Churches to the Underclass.” It would be held in late October at Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Barack agreed they should go. The weekend of “study, reflection, and worship,” as the divinity school’s dean termed it, for the two hundred attendees began on Friday evening with a sermon by Samuel D. Proctor, pastor of New York’s Abyssinian Baptist Church and one of the most famous living black preachers. Proctor’s sermon “chilled us,” one listener recounted, with its description of “the ordinary terrors of normal life in Harlem.”

Saturday morning featured a powerful and provocative lecture by Philadelphia congressman and clergyman William H. Gray. “Will we have a two-tiered society of the haves and the have-nots … or will we have a society … that allows people to move from the underclass on up?” Gray asked. For black Americans, “education is an absolute essential,” as the record was clear: “no education, no advancement,” and “blacks with no education have very little hope” of bettering their lives. Gray did not shy from naming other ills. “The leading cause of death among young black males is black-on-black crime. That’s us. Superfly selling drugs and coke in our community is not someone else. It’s us. Those who are mugging us, raping us, and robbing us are not coming from somewhere outside. It’s us. The teenage pregnancy problem is not the white man’s problem, it’s our problem…. You cannot ever escape poverty with children having children.”

Two sets of four concurrent workshops bracketed a lunchtime lecture by sociologist William Julius Wilson. After the workshops ended, Jerry and Barack took a walk around the Harvard campus. “We didn’t spend a lot of time with other people at the conference,” Kellman recalled, “just with each other.” During their stroll, Barack told him that he was applying to law schools. Kellman remembers Barack saying, “ ‘I owe it to you to let you know as soon as I can,’ ” and Kellman recalls being “very surprised.” Kellman also remembers Barack saying he did not think that community organizing was an effective means for attaining large-scale change or a practical method for influencing elected officials who potentially could. Years later Obama described his thoughts similarly, saying that “many of the problems the communities were facing were not really local,” and that he needed a better understanding of how America’s economy worked “and how the legal structure shaped that economy.” He also “wanted to find out how the private sector works, how it thinks.” By “working at such a local level” he had learned that problems like joblessness and bad public schools were “citywide issues, statewide issues, national issues” and he wanted to “potentially have more power to shape the decisions that were affecting those issues.” In a subsequent interview he would specifically cite decisions that “were being made downtown in City Hall or … at the state level.” He had been able to get “outside of myself by becoming a community organizer,” but the experience also had taught him that “community organizing was too localized and too small” to offer significant promise to those it sought to empower.

Saturday night’s dinner speaker was Children’s Defense Fund president Marian Wright Edelman, who one listener said presented a “terrifying analysis” and emphasized the need for “an ethic of achievement and self-esteem in poor and middle-class black children.” Sunday morning the symposium concluded with a sermon by Harvard professor and pastor Peter J. Gomes, who worried that after two days of “some pretty depressing statistics, some very grim predictions, some very sobering analyses” the discussion had become “so intimidating, so daunting as to lead to paralysis rather than action. With more conferences like this, one will be terrified of thinking about any form of response.” But Gomes believed the weekend’s clear message was that “money, programs, and advocacy alone will not solve the problems of the underclass.” Instead, a consensus had identified “despair as the root and fundamental disease: despair, the loss of hope, the loss of any sense of purpose, or worth, or direction, or place,” an analysis all too true to someone familiar not only with Altgeld Gardens but also Chicago’s Far South Side high schools.

Back in Chicago on Monday, Barack wrote a congratulatory postcard to Phil Boerner, who had announced his upcoming marriage to his longtime girlfriend Karen McCraw. “Life in Chicago is pretty good,” Barack wrote. “I remain the director of a community organization here, and I’m now considering going to law school. Makes for a busy life: not as much time to read and write as there used to be. Seeing a good woman, a doctoral student at Univ. of Chicago.”

The next weekend was the beginning of Gamaliel’s third weeklong training at suburban Techny Towers, with about sixty trainees joining the network’s usual roster of trainers: Greg, Mary, Peter Martinez, Mike Kruglik, Phil Mullins, Danny Solis, and Barack. David Kindler now worked under Mike at SSAC in Cook County’s south suburbs, and Kindler brought his Quad Cities friend Kevin Jokisch to the early November training. “Who you brought to training was a reflection of your ability as an organizer,” Kindler explained, and Jokisch already had hands-on experience.

“Barack was always a great trainer,” Danny Solis remembered. “He had a presence.” After sitting in on two of Obama’s sessions, Jokisch agreed. “Barack was totally in control without appearing to be in control…. His sessions flowed, were all lively, and engaged participants. He drew people out, had them tell their stories in the context of the session he was leading. His style was different than many of the other trainers. Most of the trainers were aggressive, in-your-face types.” In contrast, “Barack and Mary Gonzales had a very similar way of moving, speaking, drawing people out, utilizing humor, and probably most importantly being trusted by those in the room.”

Most nights some of the trainers adjourned to an Italian restaurant and bar just down the road. “Obama showed up twice to have beers with us. The after-hours sessions were very lively,” Jokisch recalled. “Most of the debates were around politics and politicians,” with Barack jumping in. Phil Mullins remembers how Barack “saw the limitations of just pure community organization” and asked, “How do you get at these bigger issues?” Given Gamaliel’s IAF worldview, that meant Barack “was kind of out there on his own,” and he was “constantly asking himself what he actually thinks about something,” another colleague recalled. Phil, like Kindler, also knew that among all the organizers, Barack’s real relationship was with Kruglik. “That’s the tighter person-to-person relationship” for Obama, more so than Jerry or even Greg, Mullins recounted. It was “more personal,” because as everyone could see, “Kruglik’s a warmer personality.” Given his Princeton undergraduate education, plus his graduate school history background, Kruglik’s intellectual depth and acumen were unique among the Gamaliel network. He also possessed an uncommonly superb memory.

By November 1987, Mike and Barack had known each other well for more than two years, and with Mike Barack could be spontaneous and frank to a degree he rarely was with other organizing colleagues. Even a quarter century later, Mike remembered some of what Barack said to him that week. Barack’s time in Roseland had placed him “in the armpit of the region, as far away from the center of power as you can get,” and he saw a prestigious law degree as the first step on the road to true power. Mike disagreed, telling Barack not to leave organizing and instead to commit himself to building a citywide network of organizations broader than UNO’s set of community groups, a network so sweeping that it would represent the fulfillment of what King and Al Raby had hoped the 1966 Chicago Freedom Movement would become.

Barack demurred. A top law school would give him entrée to the corridors of power. “I can learn from these people what they know about power,” and a legal education would allow him to understand “financial strategies and banks and how money flows and how power flows. Then I can come back to Chicago and use that knowledge to build power for ordinary people.” But Barack was imagining more than just building a powerful network of community groups, Mike recalled. “He said to me, ‘I’m going to become mayor of Chicago. I’m thinking I should run for mayor of Chicago.’ ”

Barack believed that Chicago’s mayor was the most powerful of any U.S. city’s, one who with widespread grassroots support could begin the rebirth of neighborhoods like Roseland. “ ‘At the end of the day, the question is, How do we lift people out of poverty? How do we change the lives of poor people, in the most profound manner?’ That’s what he was interested in,” Kruglik recounted.

And by November 1987, Barack had a specific political template in mind. “Harold was the inspiration,” Mike recalls. “Obama saw himself in a very specific way as following in the footsteps of Harold Washington … following the path to power of Harold Washington.” Ever since the mayor’s appearance at the opening of the Roseland jobs center, Barack’s attempts to win direct access to Washington had foundered. “It’s almost like he was saying to himself … ‘I’m limited by the power of Harold Washington the mayor. Therefore the answer is, I’ll be Harold Washington.’ That’s what happened,” Kruglick explains. “The Harold path was to become a lawyer, become a state legislator, become a congressman, then become mayor. That’s the Harold path.”

Barack was “fascinated with Washington,” Mike believed, and “replicating Washington step by step” was his game plan. “That was in his mind. He talked about that.” Barack “was constantly thinking about his path to significance and power,” and “Harold Washington inspired him to think about becoming a politician.”

The next Thursday was the launch of what Barack and DCP were now calling the Career Education Network’s “Partnership for Educational Progress,” a label borrowed at least in part from Chicago United’s blueprint for improving the employment skills of public high school graduates. Ever since DCP’s May decision to make education and particularly high school anti-dropout efforts a priority, Barack, Johnnie, and top DCP education volunteers like Aletha Strong Gibson, Ann West, and Carolyn Wortham had been in contact with Far South Side high school principals and guidance counselors and with officials at both Olive-Harvey College and Chicago State University. Thanks to Al Raby, who had just left his city human relations post so he could work for school reform at a newly founded consultancy called the Haymarket Group, Barack had recently met reform proponents Patrick Keleher, of Chicago United, and Sokoni Karanja.

In a fall proposal Obama would submit to multiple funders, he wrote that “the condition of the secondary school system called for a wider and more intensive campaign than we originally envisioned.” But beyond the initial $25,000 that Emil Jones had obtained from the state board of education, CEN’s only other support would be an additional $25,000 that the Woods Fund would soon officially announce.