По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

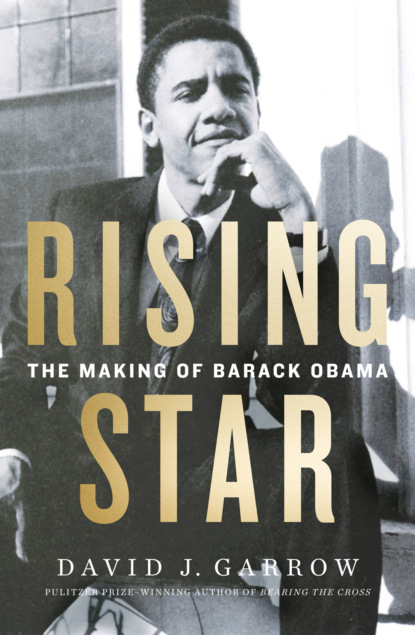

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As a native of Altgeld, Salim knew Hazel Johnson, and he had significantly helped 9th Ward alderman Perry Hutchinson, now well known for his star role in the FBI’s sting operation, win the seat he was now in danger of losing on April 7. Salim had become a Muslim under the influence of Roseland’s least-known figure of quiet political significance, Sheikh Muhammad Umar Faruqi, who oversaw a mosque on South Michigan Avenue, but Salim was not a Nation of Islam “Black Muslim.” The new jobs center would be located in a building that Faruqi and Roseland’s low-key Muslim community had acquired. Salim worked easily with Barack, whom he saw as “a very energetic and purposeful young man, with a passion to do things effectively.”

On that Monday morning, Washington and his two-man security detail arrived at the RCDC office at 33 East 111th Place. The mayor had been told he would be greeted by Loretta Augustine on behalf of DCP as well as Salim, and that Maria Cerda, Perry Hutchinson, DCP’s Dan Lee, and “Barac” Obama would be there as well. A city photographer snapped away as the hefty Washington, holding his own notes and with his trench coat thrown over his left arm, shook hands with local well-wishers as a beaming Loretta stood to his right clad in a handsome white coat. The mayor and Cerda listened carefully as Loretta thanked him for coming. One photograph captured Sheikh Faruqi a few paces behind Washington; three different photographs include a tall young man with a slightly bushy Afro standing in the rear of the small room, listening intensely to Washington and Loretta.

Obama would later quote the mayor as saying to Loretta: “I’ve heard excellent things about your work.” Then the entire group walked outside and turned south on South Michigan Avenue. With traffic blocked off and the sun in their faces, Washington and Loretta led the procession a little more than a block to the new office at 11220 South Michigan. Sheikh Faruqi trailed slightly to Loretta’s left; Cerda, 34th Ward aldermanic candidate Lemuel Austin, and state senator Emil Jones Jr. trailed to Washington’s right. At the front door of the new office, Washington, Cerda, Loretta, and a camera-hogging Perry Hutchinson posed with a white ribbon and a pair of scissors. The mayor spoke to the crowd, and then the ribbon was cut. The mayor climbed into his car for a short drive to 200 East 115th Street, where he broke ground for a future Roseland health center. Barack had emphasized repeatedly to Loretta that she should press Washington to attend a DCP rally for their Career Education Network program, but Loretta had not gotten a commitment.

In his own, overly dramatized retelling of the morning, Barack cursed in anger at her failing and stomped off while Dan Lee tried to calm him down. Loretta remembered no such scene, saying she had “never seen him angry” even when he must have been. “I’ve seen him drop his head,” but, beyond that, “he never showed it.” Tommy West agreed. “You could never see him angry.” Later that day, Barack had an initial appointment with a Hyde Park physician, Dr. David L. Scheiner, who would remember Obama exhibiting no emotional turmoil during his office visits.

On March 28, four hundred former Wisconsin Steel workers attended a seventh-anniversary rally in South Chicago, where their pro bono lawyer, Tom Geoghegan, told them he hoped their lawsuit against International Harvester—which had just renamed itself Navistar—would soon go to trial. A day earlier Frank Lumpkin and others had picketed outside Navistar’s annual meeting at the Art Institute of Chicago. Envirodyne Industries, to which Harvester had sold Wisconsin before its sudden closing, was also suing Navistar, “alleging fraud and racketeering,” the Tribune noted. The U.S. Economic Development Administration had recouped a tiny portion of its $55 million loan to Envirodyne by selling the mill as scrap to Cuyahoga Wrecking for $3 million, but Cuyahoga went bankrupt before clearing the site, leaving the rusting shell of one mill as a haunting symbol of South Deering’s past. “Frank Lumpkin deserves a spot in the organizers’ hall of fame,” the Tribune rightly observed.

On April 2, Obama joined Mary Ellen Montes and Bruce Orenstein for a joint UNO–DCP press conference in response to Mary Ryan’s private approaches on behalf of Waste Management Inc. Barack, Lena, and Bruce had decided that playing hard to get—indeed, very hard to get—would maximize the price WMI had already indicated it was willing to pay to expand its Southeast Side landfill capacity. UNO and DCP publicly embraced a no-exceptions moratorium on any new or expanded landfills, while calling for WMI to “commit to a long-term reinvestment program” for the “economic development of neighborhoods around its landfills,” the Sun-Times reported. UNO and DCP were sending a clear message they were willing to make a deal, but WMI had to be generous in purchasing their assent.

The next day, Barack again met for an hour with Greg Galluzzo—in April, as in March, they would have five hours of conversation spread over four weekly meetings. Most of Chicago was consumed by the mayoral contest that would climax on April 7. Ed Vrdolyak was running a surprisingly populist, multiethnic campaign, while Tom Hynes seemed focused on trying to take down Vrdolyak rather than targeting Washington. The Tribune heartily endorsed the mayor, saying that “Chicago is in better shape today than it was when Mr. Washington took office” in 1983. Uppermost among Washington’s “unfinished business,” the paper pointedly added, was “helping depressed neighborhoods get better housing and more jobs.”

Two days before the election, Tom Hynes dropped out, in a strategic attempt to unite white voters behind Vrdolyak. On Election Day, Washington swept through Altgeld Gardens in a voter-turnout effort, and he ultimately triumphed with almost 54 percent of the vote. One poll showed him winning 15 percent of white voters and 97 percent of blacks. In Washington’s best precinct, Marlene Dillard’s London Towne Homes, a young 8th Ward precinct captain named Donne Trotter was given credit for the mayor winning 795 out of the 798 votes cast. Citywide, Ed Vrdolyak received 42 percent, which the Tribune noted was “better than anyone had predicted.” There also was no question that “the biggest loser” was Tom Hynes, whose sullying of the family name among black Chicagoans would redound in another election two decades later. Another loser was Alderman Perry Hutchinson, who was narrowly edged out by his predecessor, Robert Shaw, in what one observer termed “a choice between two snakes.” An indictment followed just six days later, and Hutchinson was soon on his way to federal prison, where he died at age forty-eight.

Obama had attained such a glowing reputation among the CHD staffers at the Chicago archdiocese that Cynthia Norris, the thirty-year-old director of the Office of Black Catholic Ministries, requested that he conduct a training session for the eighteen delegates Chicago was sending to the National Black Catholic Congress in Washington in late May. Norris wanted the delegates to be well prepared to represent Chicago at the huge assembly, the first such gathering since 1894, and Obama trained them in the basement of Holy Name Cathedral, the famous diocesan seat just west of downtown’s Magnificent Mile.

At the end of April, Gamaliel hosted a second weeklong training session at Techny Towers in suburban Northbrook. DCP’s Margaret Bagby was among the forty or so community members who attended, along with Lena, Mike Kruglik, and CHD’s Renee Brereton, plus younger organizers such as Linda Randle. Augustana College senior David Kindler, a young trainee who had already gotten a taste of organizing work in the Quad Cities area where Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa, face each other across the Mississippi River, would remember Mary Gonzales as the star performer among an otherwise all-male and largely macho cast of trainers: Greg Galluzzo, Peter Martinez, and Phil Mullins. “Hard-assed” and “maternal,” Mary was just “phenomenally good.” Barack took charge of at least two sessions, and Kindler would recall him as someone who “likes everybody to love him.”

Galluzzo wanted to nurture and develop new, full-time organizers, and he was regularly petitioning every possible foundation to contribute to the first-year salaries of beginning organizers, just as Kellman had done with CHD and Woods when he hired Barack. Galluzzo knew that organizers must develop “sensitivity, patience and inventiveness” and understand that “he or she is there as a facilitator” who has to motivate community organizations composed entirely of volunteers. “Since every church is an important potential organizing base,” Greg said, “an organizer needs to know something of the theological and institutional characteristics of the churches in the community.”

Barack’s top priority was still his Career Education Network, and his goal was to win Washington’s support for the program. Thanks to Al Raby’s introductions at City Hall, Barack had already spoken with Luz Martinez, a relatively junior aide, about a mayoral endorsement, and in early May a seven-page document entitled “Proposal for Career Education and Intervention Services in the Far South Side of Chicago” was sent to Washington with a cover letter bearing the names of DCP president Dan Lee and now “Executive Director” Barack H. Obama. The cover letter said DCP wanted “to identify concrete ways that we can positively impact our schools” and emphasized that they “are not seeking any City funding for our program,” although they did want the mayor’s “whole-hearted support and endorsement of our program” and requested that he meet with DCP leaders sometime in the next month. They also asked that Washington “keynote a large meeting of parents and church leadership,” which DCP hoped to convene in mid-June.

In Barack’s own letter to Luz Martinez, he volunteered that Al Raby might have already mentioned DCP’s request to her or to her immediate boss, Kari Moe. The proposal said the number of blacks graduating from college in Illinois had declined since 1975, and that the dropout rate at the five Far South Side high schools was more than 40 percent. The scale of what Obama and DCP envisioned was grandiose, with “two central offices” coordinating the work of staff representatives at each high school plus supplementary personnel in various churches and social service agencies. The document said the program would give “individualized attention to at-risk students” and offer “incentives for student performance.” It would be “administered by the Developing Communities Project,” would have thirteen full-time employees as well as twenty part-time tutors, and required an annual budget of $531,000. “State funds would be used to fund this first year of the program,” with corporate and foundation support increasing the projected budget to $600,000 and then $775,000 in the two subsequent years. Obama’s plan might have seemed familiar to anyone who recalled Jerry Kellman’s Regional Employment Network and its initial $500,000 in state funding, but in this case underperforming high school students were taking the place of unemployed steelworkers.

Barack believed a key ingredient was his “Proposed Advisory Board,” a list of fifteen people who “have been invited or have already accepted” a request to participate. His list was headed by Albert Raby and state senator Emil Jones, but it also included Carver-Wheatley principal Dr. Alma Jones, Chicago State president Dr. George Ayers, and Olive-Harvey president Homer Franklin. They were followed by Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Dr. Gwendolyn LaRoche of the Chicago Urban League—whose name was misspelled—and Father Michael Pfleger. Also on the list were Ann Hallett of the Wieboldt Foundation, education researcher Dr. Fred Hess, Northwestern University’s Dr. John McKnight, and John Ayers from the Commercial Club. The list concluded with three of DCP’s most committed members: Dan Lee, Aletha Gibson, and Isabella Waller.

Obama’s proposal did not go over well at City Hall. Three of the mayor’s aides marked up the document, highlighting its astonishing scale, eye-popping budget, and the preponderance of professionals on the proposed board. One staffer wrote that it needed “more parents/local community residents, student(s), employer(s),” but even a Sun-Times story headlined “ ’85 Dropout Rate Topped 50% at 29 City High Schools” failed to elevate DCP’s request among staff priorities. Fred Hess emphasized in the Tribune how the utmost priority should be “to make the schools more accountable at the local level,” and by May powerful Illinois House speaker Michael J. Madigan, along with Danny Solis and Mary Gonzales of UNO, had embraced a Hess-drafted school autonomy pilot program, House Bill 935.

That plan would allow up to forty-six schools to operate independently of the CPS’s hierarchical bureaucracy, and when Washington appeared at UNO’s twenty-eight-hundred-person annual convention at the Chicago Hilton on May 21, he was pressed to support the bill. Washington told the crowd that UNO had “hit the nail on the head” in demanding more local autonomy, which Hess and others interpreted as an endorsement. The bill passed the Illinois House the next day, but Washington’s top aides quickly signaled that the mayor was actually opposed to such a “drastic” decentralization of CPS. Rival researcher Don Moore at Designs for Change opposed it too, and when Education Committee chairman Arthur Berman killed the measure in the state Senate, UNO acquiesced. Hess was furious, arguing that far-reaching educational changes during “the early years are the most crucial” if there was to be any hope of reducing sky-high dropout rates during high school.

Barack still sought a response from the mayor’s office to his plan, and he contacted Joe Washington, a young staffer who was a Roseland native, but made no headway. Disappointed at City Hall’s lack of interest, Barack wrote another letter to the mayor, this one featuring the names of fifteen additional signatories in addition to DCP president Dan Lee. Three were DCP members—Aletha Gibson, Isabella Waller, and Ellis Jordan, a fellow PTA leader—and twelve were Roseland clergymen: Bill Stenzel, Rick Williams, Tony Van Zanten, Paul Burak, Tom Kaminski (whose surname was misspelled), Eddie Knox (a new DCP recruit who was the recently arrived pastor of Pullman Presbyterian Church), Joe Bennett, Alonzo Pruitt, Tyrone Partee, and three more.

Obama’s inclusion of these new names suggested that a demonstration of DCP’s interdenominational support would impress either Joe Washington or the mayor. As pastors of “representative religious institutions of the Far South Side,” the signers warned that “high school age youth have been hit hard by the problems of the Chicago school system. In our area, we have seen too many youth drop out, join gangs, and turn to drugs and teen pregnancy instead of staying in school and going on to stable and successful careers.” The letter again requested a brief meeting with the mayor to discuss what was now called “a pilot Career Education and Intervention Network.” Noting that it would complement Washington’s nascent Mayor’s Education Summit, it said, “we see the urgent need for this program. We also see the need for your leadership and support in getting it started.”

But invoking the twelve Roseland pastors was not any more successful for Barack. One Washington aide jotted on the letter: “Mr. Obama is paid staff person. From Roseland upset w/ Joe.” A note to Kari Moe’s secretary instructed, “Do not schedule meeting,” and two weeks later the office file on DCP was marked “Close.” Months would pass before Barack was able to meet with one of Washington’s top aides.

By late May, Barack and DCP’s board decided to concentrate on the education project and pull back from any further employment focus. The new MOET office had been a signal achievement, but DCP’s visits to major local employers—Libby, McNeill & Libby, Carl Buddig, and Sherwin-Williams—to request that they hire local residents had only uncovered news that all three were soon closing their Far South Side plants. No one in DCP was more focused on jobs than Marlene Dillard, but this shift to education opened up tensions within the organization that began with Jerry Kellman’s initial decision to have DCP cover such a wide group of different neighborhoods. The southern trio of Altgeld Gardens, Eden Green, and Golden Gate were geographically separate from Roseland and West Pullman, and the westernmost and easternmost neighborhoods, Washington Heights and London Towne Homes, were not eager to be associated even with Roseland and especially not with the Gardens.

These divisions were personified by the differing perspectives of Loretta Augustine and her two close friends, Yvonne Lloyd and Margaret Bagby, each of whom lived just west of Altgeld, and the two different women who represented St. John de la Salle parish on DCP’s board, Marlene Dillard and Adrienne Jackson. “Certain issues I was not interested in,” Dillard explained years later. “I couldn’t center myself around individuals who were in Altgeld Gardens.” Residents of London Towne were “not on the poverty line,” and although they worried about job loss, they did not require the most basic job training skills that most Altgeld residents needed. In addition, “my son went to a private school,” so Roseland’s failing public high schools likewise were not a high priority. “I don’t feel that London Towne and Roseland can be linked together,” for “we have different values and different interests.”

Yvonne Lloyd, who lived near Altgeld in Eden Green, agreed with Dillard’s explanation. The areas “had different problems” and indeed were “totally different” because solid residential areas like London Towne had “facilities that Altgeld didn’t.” She, like Margaret and especially Loretta, believed Altgeld’s scale of deprivation meant it should be DCP’s top concern, because “those were the people we were really, really concerned about” the most. Betty Garrett, the gentle mainstay of Bill Stenzel’s congregation at Holy Rosary, watched as the divide deepened between Loretta and Marlene. “They fought constantly,” she recalled, mostly over Dillard’s emphasis on jobs. “Loretta wanted it to be more widespread.” Marlene understood that Loretta “was more interested in poverty issues” than she was, and over time her attitude became “let Loretta and them take care of Altgeld Gardens.”

Barack was very close to both Loretta and Marlene, often talking with Marlene’s mother and helping Marlene when she ran for election to London Towne’s board of directors. Yet by May 1987, there was no getting around the power struggle within DCP, and how Loretta’s viewpoint was more widely shared than Marlene’s. “Barack was the person who held it together” as long as it did hold, Marlene recalled, but after the May meeting, she shifted her attention to DCP’s nascent landfill alliance with UNO’s Southeast Chicago chapter.

If DCP hoped to make Barack’s Career Education Network even a modest-sized reality, it needed a second full-time organizer, such as Johnnie Owens, and the money to pay his salary. By late spring 1987, Barack had submitted his grant proposal to the MacArthur Foundation, where it went to Aurie Pennick, an African American and South Side native. MacArthur had little experience with community organizing, but soon after Pennick’s arrival in 1984, she had initiated a program called the Fund for Neighborhood Initiatives, which would direct about $700,000 annually toward “revitalizing some of Chicago’s poorest communities.” The small world of Chicago philanthropy was highly interactive, and Pennick had heard Ken Rolling speak glowingly about DCP and was aware that it was being funded by Woods, Wieboldt, and CHD. Pennick lived in West Pullman and her daughter attended Reformation Lutheran’s small school on 113th Street, so she knew of DCP’s connection there too. But when she read Barack’s proposal, she was “underwhelmed” by it. Pennick was deeply averse to the “top-down” type of projects that often won CHD support, and instead favored indigenous activists such as Hazel Johnson from Altgeld. She met with Barack and a trio of DCP members—Loretta, Marlene, and Yvonne—but came away with mixed reactions.

In every such meeting, as with city council leader Tim Evans almost a year earlier, Barack insisted that his community members take the lead while he remained almost silently in the background. “He would never speak. He always put us out front,” Cathy Askew explained in recalling a time when she and Marlene accompanied Barack to a meeting with Jean Rudd at Woods. All of the DCP women remember Barack picking them up in his small blue car; wintertime appointments downtown were more memorable than summer ones because Barack’s car had a hole in the floor and little if any heat. Yvonne Lloyd remembered the preparations for the MacArthur meeting, with Barack insisting that she, Loretta, and Marlene have the speaking parts and not him. “ ‘You have to be the ones to actually do it because this is your community, not mine,’ ” Lloyd recalled him saying. “ ‘You can tell your story better than I can.’ ”

Aurie Pennick found Loretta Augustine “very articulate, very smart” at DCP’s meeting with MacArthur. “I was impressed with her. Barack was a little skinny guy in the back, said very little.” Yet Pennick’s South Side roots left her uncomfortable with how DCP “was very much noninclusive of lower-income folk,” such as the actual residents of Altgeld. She also detected a “kind of classist thinking” in some of the DCP members’ statements. Pennick told them she had not heard about them being active in West Pullman and asked Barack if DCP had held community meetings there. He assured her that DCP did have a presence there, but when the meeting ended, Pennick “wasn’t sure whether MacArthur would make a grant.” In subsequent days, when Pennick asked her immediate neighbors if they were familiar with DCP, no one was, and she decided that DCP was “too new and lightweight” to merit MacArthur funding.

To bolster DCP’s dropout prevention focus, Barack wanted to generate parental interest in his CEN idea before school ended in early June. He and his two most energetic education volunteers, Aletha Strong Gibson and Ann West, called on the principals of all five Roseland area high schools and asked if they could hold “parent assemblies” in Roseland, Altgeld, Washington Heights, and West Pullman. Barack “was very professional … very articulate,” Ann West recalled. “He was driven, and he was committed…. It didn’t appear to be just a job.” Aletha felt similarly, describing Barack as “heartfelt” and “committed to the people” as well as “very charismatic.” He spent many hours with Aletha and Ann, but even though he knew Aletha had spent her junior year of college in Kenya, and that Ann was a white Australian woman married to an African American, Barack never said anything about his father or about Genevieve. “He was so private,” Ann remembered, and they knew nothing of his personal life. “He didn’t mix the two.”

DCP’s members collected a repertoire of Obama’s stock expressions, which became something of a running joke. Margaret Bagby remembered, “Whenever he tells you, ‘I don’t think,’ he’s telling you that he knows what he wants. And you really need to look out when he says, ‘My sense is that.’ ” Ann West recalled, “He would say to us, ‘This is what we need to do,’ ” and if he were asked a question and he didn’t know the answer, he would reply with one or both of these phrases: “Let me look into it” and “I’ll research it,” Yvonne remembered. They could all see, as Yvonne explained, how “precise and thorough” Barack was in making plans.

One Saturday morning before DCP’s “parent assembly” in West Pullman, Aurie Pennick was doing yard work in front of her home, when “all of a sudden I hear ‘Miss Pennick’ ” from someone who recognized her from behind. It was Barack, passing out flyers for DCP’s upcoming meeting. “This is a smart man. He probably figured out where I live,” Pennick immediately realized. DCP’s leafleting was extensive, and Pennick remembers going to the meeting “and it’s packed…. They really had thought it out,” and Barack’s careful strategizing paid off just as he had hoped. “I of course made the grant,” Pennick explained, and in September DCP received $20,000 from MacArthur for general operating support—exactly what was needed to pay Johnnie Owens’s salary.

Owens came from a working-class black family, and for him wearing a shirt and tie to Friends of the Parks’ downtown office was far more inviting than working out of DCP’s windowless office on the ground floor of Holy Rosary’s small rectory in Roseland. But Obama was determined to hire him, and Owens recalls Barack challenging him by saying things like, “ ‘If you’re really interested in changing neighborhoods and building power, you can’t do it from downtown.’ ” To sweeten the deal, Barack gave Johnnie money from DCP to buy a car, and yet was royally pissed when Owens got a brand-new Nissan Sentra, which was far swankier than the rapidly aging Honda Civic Obama was still driving. “We always had a little tension about that,” Owens remembered, but Barack was exceptionally happy to have Johnnie start in July.

DCP’s work in West Pullman had attracted some new members, including Loretta’s friend Rosa Thomas and a young housewife, Carolyn Wortham, but Barack’s grand plans for a half-million-dollar-a-year CEN depended on support from Emil Jones and the Illinois state legislature, which would be struggling with the state budget through June. Barack organized a lobbying trip to Springfield and took some of DCP’s most devoted members—Dan Lee, Cathy Askew, and Ernie Powell, Loretta and her friend Rosa Thomas, several other ladies, Ellis Jordan, as well as Loretta’s young daughter and both of Cathy’s. Emil Jones was a gracious host, posing with the whole group for a photo in his office. Dan Lee’s dark jacket and white pocket square matched his mod eyeglass frames all too well, Loretta looked lovely in a stylish white dress, and Ernie Powell personified strong workingman dignity with a well-knotted tie below one of Illinois’s more impressive mustaches. Barack wore a blue blazer, a white shirt, and no tie, but he closed his eyes when the camera clicked. Barack’s dream of obtaining a $500,000 state appropriation remained just that, although Jones arranged for the Illinois State Board of Education to give DCP a $25,000 planning grant that gave Barack enough to get a semblance of CEN started in early 1988.

Back in Chicago, Obama continued his almost weekly discussions with Greg Galluzzo, who told numerous organizing colleagues that Barack was “really special.” But even though Greg spent more time with him than any other person in Barack’s workday world, he knew almost nothing of Barack’s home life, and he met Sheila Jager only once in passing.

The young couple’s first nine months of living together had melded two intensely busy lives into an increasingly cloistered relationship where Sheila saw almost no one from Barack’s day job, and Asif was their only regular contact in Hyde Park’s graduate student community. Barack’s heavy smoking was a regular topic of comment within DCP, and Reformation Lutheran pastor Tyrone Partee nicknamed him “Smokestack.” Sheila said that at home, “he actually introduced me to smoking, so we smoked like chimneys together.” She wanted a cat, and after Barack relented, “Max” joined their household and became a less-than-fully-welcome presence in Obama’s life. “He drove Barack crazy because the cat would always pee” in their one large houseplant.

Sheila recalls the early months of 1987 as a time when she witnessed a profound self-transformation in Barack. “He was actually quite ordinary when I met him, although I always felt there was something quite special about him even during our earliest months, but he became someone quite extraordinary … and so very ambitious, and this happened over the course of a few months. I remember very clearly when this transformation happened, and I remember very specifically that by 1987, about a year into our relationship, he already had his sights on becoming president.”

This change in Barack encompassed two interwoven themes: a belief that he had a “calling,” coupled with a heightened awareness that to pursue it he had to fully identify as African American. The “ ‘calling’ had more to do with developing a sense of purpose in the world,” Sheila later explained, and even two years earlier, Genevieve Cook had sensed an incipient presence of the same thing. She remembered thinking that “all along he had some notion of testing his own mettle and potential for greatness, and that it was as much about that personal journey as it was finding the best way to effect the maximum positive social change. Those two aspirations, the personal and the heroic,” were “melded from very early on.” Yet by early summer 1987, Barack’s understanding of his “calling” was as “something he felt he really had no control over; it was his destiny,” Sheila explained. “He always said this was destiny.”

By then, Barack had gotten to know Al Raby and John McKnight, whose political roots lay in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, and he had a relationship with Jeremiah Wright, whose theology sprang from that same soil. Barack had also developed an acquaintance with Emil Jones, a savvy politician, and he had witnessed at close range the charm and aura Harold Washington possessed even in a nondescript storefront. But as Sheila experienced and reflected upon what occurred, she realized the stimulus for Barack’s transformation lay not in one or another precinct of black Chicago, but in the disparaging evaluation he had received from her father back at Christmas. “After that visit, and over the course of spring ’87, he changed—brooding, quiet, distant—and it was only then, as I recall, that he began to talk about going into politics and race became a big issue between us.” Once “we got back from California,” Barack “became very introspective and quiet,” Sheila recalled. “I remember very specifically that it was then he began to talk about entering politics and his presidential ambitions and conflicts about our worlds being too far apart.”

Meanwhile, “the marriage discussion dragged on and on,” but it was affected by what Sheila describes as Barack’s “torment over this central issue of his life,” the question of his own “race and identity.” The “resolution of his ‘black’ identity was directly linked to his decision to pursue a political career,” and to the crystallization of the “drive and desire to become the most powerful person in the world.”

Eight years later, Obama would say that through organizing “I think I really grew into myself in terms of my identity,” and that his community work “represented the best of my legacy as an African American.” It had allowed him to feel that his “own life would be vindicated in some fashion,” and his immersion in black Chicago gave him “a sense of self-understanding and empowerment and connection.” Obama’s daily experiences on the Far South Side had reshaped him. “I came home in Chicago. I began to see my identity and my individual struggles were one with the struggles that folks face in Chicago. My identity problems began to mesh once I started working on behalf of something larger than myself.” He also explained that organizing had “rooted me in a specific community of African Americans whose values and stories I soaked up and found an affinity with.” And most specifically, “by the second year,” he told one interviewer, “I just really felt deeply connected to those people that I was working with.”

Sheila was convinced that “something fundamentally changed” inside Barack during the first half of 1987 that had transformed him into a “powerfully ambitious person” right before her eyes. “We lived so cut off from everyone else” that no one else was privy to her perspective, and Barack’s ability to “compartmentalize his work and home life, to the extent that the two worlds were never brought together physically” or in any social setting, meant that their increasingly stressed and intense relationship existed as “an island unto ourselves.”

In later years, Obama once said that his experiences in Chicago had “converged to give me a sense of strength.” At an expressly religious event, he cited Roseland as where “I first heard God’s spirit beckon me. It was there that I felt called to a higher purpose.” Sheila caviled at that, saying she “would not call him religious. Perhaps spiritual is a better description” of the man she lived with. “Barack was definitely not religious in the conventional sense. He talked about God in the abstract, but it was mostly in terms of his destiny and/or some spiritual force.”

Early in the summer, Barack’s older brother Roy visited Chicago and met Sheila briefly, but Barack went alone to the Chicago home of his maternal uncle Charles Payne for his nephew Richard’s high school graduation. His sister Maya had just completed her junior year at Punahou, and she wanted to visit a number of mainland colleges before submitting her applications. Ann Dunham was attending the Southeast Asian Summer Studies Institute being held at Northern Illinois University, west of Chicago in DeKalb, so she and Maya arrived in Chicago before Sheila left to see her parents in California and make a brief initial research trip to South Korea.

This was the first time Barack and Ann had seen each other in eighteen months, and Ann had gained a tremendous amount of weight and now seemed “very matronly.” She had not made much headway on her Ph.D. dissertation, in part because she had spent half of 1986 in the Punjab, working as a consultant for the Agricultural Development Bank of Pakistan. But her analysis was coming together, and one of her closest academic colleagues described her conclusions in words that echoed what her son had learned from John McKnight. “Anti-poverty programs … only reinforce the power of elites” and “it is resources and not motivation that poor villagers lack,” in Indonesia as elsewhere. Once Ann’s summer institute was complete, she would return to Pakistan for three more months of work. Barack’s close friend Asif Agha recalled playing volleyball out at Indiana Dunes during Maya’s visit, and Jerry Kellman remembers Barack bringing Maya along to a barbecue at Jerry’s home. During this trip, Maya wanted to see the campuses of the University of Michigan and the University of Wisconsin, where Asif spent much of the summer studying Tibetan.

Early in the summer Barack decided that he and Sheila should acquire a new Macintosh SE computer, which had debuted just three months earlier. “It was the latest model and very fancy,” Sheila remembered, and as with their rent, Barack happily footed the bill. “Barack said we both needed it,” and they each used it a lot, but when it first arrived, Barack had no idea how to operate the mouse. A call to Asif resulted in the dispatch of Asif’s other best friend, Doug Glick, a fellow linguistic anthropology graduate student who quickly showed Barack that you do not hold the mouse up in the air.

By the end of June, with Sheila away from Chicago and Asif up in Madison, Barack and Doug on several weekends made the three-hour drive up to where Asif was housesitting in some Wisconsin professor’s lakefront home. Obama years later would publicly joke that he had had “some fun times, which I can’t discuss in detail,” on those visits and “some good memories,” but Glick clearly remembered the long drives in Barack’s noisy Honda. Barack was “just a regular guy,” an “incredibly friendly guy” with “a great sense of humor.” During the road trips, Barack talked “about wanting to write the great American novel…. I spent an awful lot of time in the car with him. These are long drives, he can talk,” and “he doesn’t shut up.” At least once Obama mentioned an interest in law school, but he rarely talked about his DCP work. “I never heard him talking about community work and public service as the driving force of who he was.” Sometimes “I’m making fun of him,” asking, “ ‘If I whisper “shut up,” will you hear it with those ears?’ ” But Barack clearly had “tremendous intelligence, tremendous charisma,” and indeed “a certain kind of aura to him,” Glick thought. Doug, like Asif, felt that “Barack is not that black,” but it also seemed as if “he was ideologically loaded a little.”

During one drive, Glick recounted, “we had a god moment. The strangest thing that has ever happened to me in my life happened with him.” Every trip included a pit stop to get gas and pick up something to drink, and on one occasion Barack was “sitting in the car in the driver’s seat” with the window open as Doug returned carrying snacks and bottles. “I tripped. The Snapple goes flying…. We both watch as it hits the ground, breaks like an egg, goes up through the air, goes through the window and both of the things land on his legs face up.” Yet somehow Obama was completely dry. “We’re never going to forget that,” Barack said to Doug. “Religions start at moments like that.”

In Chicago, the battling intensified over the Southeast Side landfills and their toxic impact on nearby residents. The Sun-Times published a six-part, front-page series of stories titled “Our Toxic Trap” which focused on CID, the Metropolitan Sanitary District’s (MSD) “shit farm” just north of Altgeld Gardens, and older, more mysterious dumps like the Paxton Landfill. Hazel Johnson was quoted on the “nauseating stench” of sewage sludge permeating Altgeld and said, “it smells just like dead bodies.” In response, the state legislature created a special joint committee to investigate the problems, and the MSD’s board pledged its own study after an angry public meeting during which Johnson called one African American MSD commissioner an “Uncle Tom.” After a large illegal dump was discovered in a remote corner of Auburn Gresham, four city sanitation workers who were excavating the waste for transfer were “overcome by noxious garbage fumes” and hospitalized.

On June 30, WMI’s Mary Ryan proposed to Chicago’s city council that if the city would set aside its existing moratorium on landfill growth, WMI would move forward with an “economic and community development assistance program” that could be a huge “ ‘catalyst’ toward revitalizing” the entire Southeast Side. But Ryan’s proposal only intensified the fury of local activists like Marian Byrnes, Vi Czachorski, and Hazel Johnson over a possible deal between the city and WMI to expand landfill capacity. “Perhaps Washington is Vrdolyak in disguise on dump issues,” James Landing, the chairman of the Lake Calumet Study Committee (LCSC), told his fellow allies.

With a new and energetic Chicago chapter of the international environmental group Greenpeace eagerly joining in, Southeast Side activists prepared for a July 29 blockade of all dumping at CID. A large rally drew media coverage, and a dozen or more Greenpeace members and local activists would chain themselves together to CID’s entrance gate to block waste trucks from entering the landfill. By the morning of the twenty-ninth, DCP’s Dan Lee, Cathy Askew, Margaret Bagby, Loretta Augustine, Betty Garrett, and Obama joined the protesters. Cathy recalled years later, “He led that. He led that in the background. He had to be there to bail them out.”

The day was “beastly hot,” one young Greenpeace member remembered, and “wearing a media-friendly buttoned-down shirt” became a sweaty mistake. But the blockade was a grand success. The Daily Calumet reported that a crowd of 150 people gathered and said it was “the largest environmental protest in years.” As many as a hundred waste trucks were backed up on the nearby expressway and unable to enter CID, as protesters chanted, “Take it back!” They blocked the entry gate from 10:00 A.M. until midafternoon. One photo caption said: “Wearing a gas mask, Deacon Daniel Lee of the Developing Communities Project … makes a point about odors and toxic wastes.”

Some reporters lost interest as the day dragged on, and the next morning’s Sun-Times erroneously reported that “there were no arrests.” Leonard Lamkin, an East Side activist who joined the chain-in, said that “when the media went away, that’s when they made the arrests.” Hazel Johnson and Marian Byrnes were among the sixteen participants taken into custody, and the women remained jailed for six hours even though the men were released in less than two. Scott Sederstrom, the young, overdressed Greenpeacer, thought “it was almost an act of mercy by the Chicago police to take us into their air-conditioned precinct house for booking…. The Cubs game was on TV in the station” and comments about baseball leavened the fingerprinting process. “As a further act of generosity, they let me stay in the air-conditioned area watching a little more of the game” instead of moving Sederstrom to a holding cell. Given the Cubs’ all-too-typical performance, though—they were trailing 10–0 by the seventh-inning stretch—interest in the game understandably waned. Weeks later the charges were dropped against defendants who agreed not to enter any WMI properties for one year.