По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

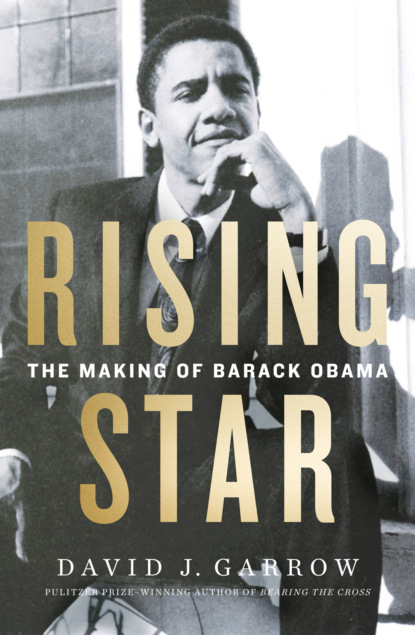

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

From the beginning, Bonnie thought Barack “was more together, more poised” than his older coworkers, and Bill recalled that Barack became “very curious” about religious faith while suddenly being surrounded by so many committed Catholics. “He had a curiosity about what’s this phenomenon” and a “very respectful” attitude toward faith. Obama asked if he could attend Sunday mass, and Bill can recall him sitting with the congregation. Jerry Kellman was about to convert to Catholicism, and he understood how “the churches we dealt with were extended families,” ones that exposed Obama to “a broad sense of religion.” For Barack “his sense of church and his sense of God became very much a community experience,” and “it was a very formative period” for him, Jerry explained. Obama often drank coffee with Tom Kaminski, and they talked “about all sorts of things,” including family, but Fred Simari believes that Obama’s time in the kitchen at Holy Rosary had the most impact. “Bill Stenzel spent a tremendous amount of time with Barack,” and “some of that spiritual-type formation” that Bill exuded “wore off on Barack, there’s no doubt.”

That fall, Barack continued his one-on-one conversations with pastors like Bob Klonowski of Lebanon Lutheran in Hegewisch and Catholic parishioners like Loretta Augustine at her home west of Altgeld Gardens. “It was surprising how receptive people were to talking with him,” Loretta remembered. Tom Kaminski noted “what a terrific listener he was” and watched as Barack’s acceptance spread. At the three-month mark, Obama’s $10,000 trainee salary was doubled to $20,000, the apprentice director salary that Kellman had advertised five months earlier.

Meanwhile the warfare between Harold Washington and the city council majority opposed to him, led by South Chicago’s 10th Ward Alderman Ed Vrdolyak, was constantly in the headlines. Washington had accepted UNO’s invitation to speak at its annual fund-raising banquet on October 30, where the mayor would present a thank-you award to the archdiocesan Campaign for Human Development (CHD). Attendees were greeted outside by picketers led by South Deering Improvement Association president Foster Milhouse, who told reporters, “We want UNO out of our neighborhood, and we want Father Schopp and UNO out of St. Kevin’s.” The far right’s complaints continued with a letter to the editor of the Daily Calumet denouncing CCRC and UNO and calling for concerned citizens to “rid their communities of these revolutionaries.” An anti-UNO rally at the Calumet City American Legion hall featured Foster Milhouse and attracted a crowd of about a hundred, and another letter to the Daily Cal thanking the paper for its coverage warned of the philosophy of the “anti-God idolizer of Lucifer” Saul Alinsky.

With UNO adding affiliates in other Hispanic neighborhoods, Mary Ellen Montes chaired an evening meeting that drew a crowd of two thousand. Mayor Washington, Governor Thompson, and powerful Illinois House speaker Michael J. Madigan all joined Lena on stage, but afterward she denounced Thompson’s refusal to commit $6 million for a new West Side technical institute. UNO and other Southeast Side groups continued to fight against any expansion of the area’s overflowing landfills, but with city officials all too aware of Chicago’s looming garbage crisis, Washington’s aides maintained an ominous silence on the issue. City officials had finally acknowledged that the well water samples from the isolated Maryland Manor neighborhood south of Altgeld Gardens “definitely contain cyanide,” but the projected cost of $460,000 to extend water and sewer lines to those taxpayers’ homes postponed any remedial action, even though the Tribune and the Chicago Defender ran prominent news stories about the problem. More than a year would pass before the work was carried out.

In mid-November Obama was finally able to write a long letter to Phil Boerner. “My humblest apologies for the lack of communication these past months. Work has taken up much of my time,” but now “things have begun to settle into coherence of late.” Barack described Chicago for Phil, calling it “a handsome town” with “wide streets, lush parks,” and “Lake Michigan forming its whole east side.” Although “it’s a big city with big city problems, the scale and impact of the place is nothing like NY, mainly because of its dispersion, lack of congestion.” Chicagoans are “not as uptight, neurotic, as Manhattanites,” and “you still see country in a lot of folks’ ways,” but “to a much greater degree than NY, the various tribes remain discrete…. Of course, the most pertinent division here is that between the black tribe and the white tribe. The friction doesn’t appear to be any greater than in NY, but it’s more manifest since there’s a black mayor in power and a white City Council. And the races are spatially very separate; where I work, in the South Side, you go ten miles in any direction and will not see a single white face” excepting in Hyde Park, a considerable exaggeration on Obama’s part. “But generally the dictum holds fast—separate and unequal.”

Obama said his work took him to differing neighborhoods, with residents’ concerns ranging from sanitation complaints to job-training programs. “In either situation, I walk into a room and make promises I hope they can help me keep. They generally trust me, despite the fact that they’ve seen earnest young men pass through here before, expecting to change the world and eventually succumbing to the lure of a corporate office. And in a short time, I’ve learned to care for them very much and want to do everything I can for them. It’s tough though. Lots of driving, lots of hours on the phone trying to break through lethargy, lots of dull meetings. Lots of frustration when you see a 43% drop out rate in the public schools and don’t know where to begin denting that figure. But about 5% of the time, you see something happen—a shy housewife standing up to a bumbling official, or the sudden sound of hope in the voice of a grizzled old man that gives a hint of the possibilities, of people taking hold of their lives, working together to bring about a small justice. And it’s that possibility that keeps you going through all the trenchwork.”

But Obama’s most vivid image was the one Kellman had shown him three months earlier in South Deering: “closed down mills lie blanched and still as dinosaur fossils. We’ve been talking to some key unions about the possibility of working with them to keep the last major mill open, but it’s owned by LTV,” which “wants to close as soon as possible to garner the tax loss,” Barack told Phil. He ended the letter by saying his apartment was “a comfortable studio near the lake” and that “since I often work at night, I usually reserve the morning to myself for running, reading and writing.” He enclosed a draft of a short story dealing with the black church and asked Phil to mark it up and return it. “I live in mortal fear of Chicago winters,” and “I miss NY and the people in it … Love, Barack.”

The letter documented several significant turning points in Barack’s new life. Most important of all was the emotional attachment Barack had already developed toward the people on whose behalf he was working: I “care for them very much and want to do everything I can for them.” The second was that now, more than three months in, Obama was much more comfortable with his weekday work. As his close friend Asif Agha remembered, “in the beginning, he was enormously frustrated because the whole scene was completely chaotic,” but in “struggling with those frustrations,” Asif witnessed Barack “coming together around them as a purposeful person.” Kellman was focused on the jobs bank and his initial contacts with Maury Richards’s Local 1033 at LTV Republic Steel, but Obama’s workday involved interactions with DCP’s core participants—Loretta Augustine and Yvonne Lloyd from Golden Gate and Eden Green, down near Altgeld Gardens, Dan Lee and Cathy Askew from St. Catherine of Genoa in struggling West Pullman, Betty Garrett and Tom Kaminski from central Roseland, and Marlene Dillard from the solidly working-class London Towne Homes well to the east—which presented daily challenges that were mundane as well as relentlessly unceasing.

Yet as close as Obama became with Loretta and Dan, as well as to white priests like Bill Stenzel and Tom Kaminski, he had no closer a bond with anyone than Cathy Askew, the white single mother of two “hapa” daughters—half black, half white. Askew was a small-town Indiana native whose family had shunned her after she married an African American who fathered her two daughters, then disappeared entirely from their lives. Cathy taught school at St. Catherine’s, and one of her daughters, Stephanie, had a congenital heart condition that left her less than fully robust. Early on Obama told Cathy about his own father and mother. As a result, “I don’t think of him as really like African American. He’s African, and he’s American,” she said. As he later wrote, Barack also recognized “the easy parallels between my own mother and Cathy, and between myself and Cathy’s daughters, such sweet and pretty girls whose lives were so much more difficult than mine had ever been.”

Having lived with a black man, Cathy saw Barack as something else: “he didn’t look African American to me. I was really glad to find out he was a hybrid, because my kids are hybrids.” From the beginning, she thought Barack “was gawky … very quiet … very thoughtful,” she remembered. In those early months, he “was at a loss for a long time, I think, over where to focus…. I saw him doing a lot of listening to people and trying to pull things out of people. There was no focus. Everybody seemed like they wanted something different and nobody had anything in common.”

Early that winter, Obama organized a meeting at St. Catherine for area residents to voice their unhappiness about police responsiveness to the district commander. Hardly a dozen people showed up, and the commander was a no-show too. Years later, Obama would repeatedly recall that evening. Loretta had been there, as well as Cathy. “He got frustrated. I think he almost quit once,” Cathy said. Obama would recount even his core members saying they were tired and ready to give up, and “I was pretty depressed.” As he remembered, across from the church, in an empty lot, two boys were tossing stones at an abandoned building. “Those boys reminded me of me…. What’s going to happen to those boys if we quit?”

At the beginning of December, Chicago’s steel industry was back in the news. Eighteen months earlier, Mayor Washington had appointed a Task Force on Steel to study the industry’s future, and its report demonstrated that the entire effort had been a waste of time and energy. Early on Frank Lumpkin and his Save Our Jobs Committee colleagues had hoped the task force would show that their ideas about government investment could revive one or more Southeast Side mills. Washington sympathized with these hopes, but the task force brushed aside Lumpkin and his sympathizers. Its primary academic consultant, Ann R. Markusen, asserted that “Reaganomics and industrial leadership (or lack of it) deserve the major blame” for the plant closings and added that Chicago was “a city in deep, long-term trouble.” She also acknowledged that “national and international forces beyond the grasp of local governments are important determinants of steel job loss.” Task force member David Ranney stressed that in retrospect the “idea that the steel industry in Chicago might recover appeared absurd” and that what the Far South Side experienced during the 1980s “highlights the limits of local electoral politics.”

During November and December, Maury Richards from USW Local 1033 and Jerry Kellman from CCRC met four times with Chicago’s economic development commissioner, Rob Mier, one of Washington’s most influential aides, to determine how they should react to the loss of a thousand or more jobs if there were even a partial shutdown of LTV’s East Side mill. Mier knew that this would be “a severe blow” to the city because a majority of the steelworkers lived in Chicago, and the mill paid $18 million a year in city and state taxes while contributing $300 million to the city’s economy. The union, CCRC, and Mier agreed that everything possible had to be done to convince LTV to invest $250 million to rebuild a blast furnace and acquire a continuous caster, or alternatively to sell the aging plant to a company that would. “Most of the discussants seem to realize that neither of these outcomes may be possible,” Mier told the mayor. Noting that LTV held defense contracts worth $1.3 billion, Mier reported that “both CCRC and Local 1033 are committed to coordinating a corporate campaign against LTV if LTV refuses” to invest or sell.

Obama, Loretta Augustine, and Marlene Dillard went with Jerry to one or more of his meetings with 1033’s officers and city officials, though no one except Jerry spoke on CCRC’s behalf. On December 19 Kellman and Richards sent a formal letter to the mayor, copied to Mier, asking Washington to “provide the leadership,” in coordination with local congressmen, that would pull together a package of city, state, and federal financial incentives for LTV. The Christmas holidays stalled these actions, but in the press, LTV called its Chicago mill “more vulnerable” than its remaining ones in Ohio and cited its massive $2.6 billion debt burden, intimating that bankruptcy was far likelier than any investment of capital in the East Side plant.

Over the holidays, Barack took off almost two weeks, flying first to Washington, D.C., to meet his—and Auma’s—older brother Roy Abon’go, who had married an African American Peace Corps volunteer named Mary. Before leaving Chicago, Barack told Tom Kaminski how apprehensive he was about seeing Roy, and the visit got off to a bad start when Roy failed to meet him at the airport. When Barack telephoned, Roy said a marital argument meant that Barack should find a hotel room rather than stay with Roy. The two brothers did have a long dinner that night, plus breakfast in the morning, before Barack headed to New York, where he would rendezvous with his mother and sister and where Beenu Mahmood and Hasan Chandoo were happy to offer free lodging and renew their close acquaintances.

Maya was now a tenth grader at Punahou, and Ann was still living in Honolulu, trying to finish her Ph.D. dissertation. Two months earlier, the Internal Revenue Service had levied a $17,600 assessment against her for unpaid taxes on her 1979 and 1980 income from USAID contractor DAI, but Ann would leave the levy unpaid for years to come. Barack ended up spending more time with Hasan, Beenu, and Wahid Hamid than with his mother and sister, and though he did not see Genevieve in person, a letter he wrote to her soon after New Year’s recounted an emotional phone conversation they had had, albeit one she would be unable to recall in any detail years later.

Hard guy that I am, I’ve managed to stay embittered and sullen towards you for a whole week and a half. But that’s about it. I won’t try to analyze whether what I did was correct or incorrect, right or wrong, for you or for me. I do know that I had to vent my feelings fully; otherwise I would have choked off something important inside me, permanently. Had to get my head and heart in better communication with each other, in better balance. The consensus seems to be that the whole episode was good for me. My mother and Maya enjoyed comforting me for a change. Asif, my linguist friend in Chicago, says I need the humility.

Whatever had transpired, Barack wrote, “reminded me of the rare, fleeting nature of things. My own dispensability,” and “perhaps I’m more apt to believe now something you seem to have understood better than I—when happiness presents itself … grab it with both hands.” But “I still feel some frustration at the fact that you seemed to have wrapped me up in a neat package in our conversations. Stiff, routinized, controlled. The man in the grey flannel suit. A stock figure. It felt like you had forgotten who I was.”

Friends, Barack wrote, “recognize who you are … even when you’re acting out of character,” as Barack apparently had. “I hope I haven’t lost that with you. I hope I remain as complicated and confusing and various and surprising in your mind as you are in mine.” He closed by saying that “phone calls will still be tough on me for the time being, but cards or letters are welcome.” He hoped to get back to New York in the summer to see the child whom Wahid and his wife Filly were expecting, and “hopefully we can spend some time more productively than this last time out. Some fun, maybe. Laughter. Ambivalently yours. But w/ unconditional love—Barack.”

More than six months since they had parted, the depth of Barack’s emotional tie to Genevieve remained powerful indeed.

While Obama was away, two major developments upended Chicago politics. The Chicago Sun-Times gave Harold Washington a stinker of a Christmas morning gift by revealing that an undercover FBI informant, working at the behest of the local U.S. attorney, had made cash payoffs to several city officials and aldermen. As the story played out over the coming weeks, Michael Burnett, aka Michael Raymond, had been introduced to his targets by a “friendly, easy-going” young lobbyist, Raymond Akers, whose car sported a personalized license tag: LNDFLL. Akers was the city council lobbyist for Waste Management Incorporated (WMI), which had 1985 revenues totaling $1.63 billion.

Four months earlier two administration appointees had accepted as much as $10,000 in cash from Burnett, and on December 20, FBI agents had confronted 9th Ward alderman Perry Hutchinson at his Roseland home. On two occasions in early October, Hutchinson had accepted a total of $17,200 from Akers in a lakefront apartment near Chicago’s Navy Pier. Unbeknownst to Hutchinson, FBI agents in the apartment next door filmed the encounters with a camera inserted through the common wall. A week later Hutchinson accepted another $5,000 from Akers in Roseland. All told, Hutchinson had received $28,500, and he told journalists, “I figured as long as the guy was dumb enough to give me all of that money, I’d be smart enough to take it.” Hutchinson claimed he used $8,500 to hire an additional staffer and had distributed the remaining $20,000 to schools and community groups in Roseland. Reporters were unable to identify any recipients.

Soon it was revealed that a second black alderman and mayoral supporter, Clifford Kelley, who had led a city council effort to discredit a top WMI competitor, had accepted cash bribes too. Then news broke that city corporation counsel James Montgomery allegedly had been aware of at least one of these payoffs months before Washington first learned of the bribes on Christmas morning. The Chicago Tribune described this as “a widening scandal that some believe could cost [Washington] re-election” a year later. Montgomery quickly resigned, but several weeks later a Tribune story headlined “Lobbyist Paid for City Aide’s Vacation” showed that a year earlier, Akers had given a travel agent $4,200 in cash to cover a weeklong trip to Acapulco for Montgomery and his family. No charges ensued.

Independent white voters who loathed Chicago’s long history of public corruption had been essential to Washington’s 1983 triumph, and they would be needed for his reelection in 1987. Ironically, as the controversy built, mayoral opponents like Ed Vrdolyak remained largely silent. One opposing alderman explained to the Tribune: “If we do nothing, the mayor might ultimately bury himself.”

Despite Washington’s huge popularity among African Americans, his first three years in office had been anything but successful. Some months earlier, Chicago Magazine—not a bastion of Vrdolyak supporters—had published a thoroughly negative report on Washington’s record to date. He “has been miserably inept at communicating his ideas to the city” and “his administration is plagued by excessive disorganization,” Chicago reported. Washington had “gained 30 pounds” and looked “physically run-down.” One black activist who had championed his election back in 1983, Lu Palmer, complained that Washington was relying upon “apolitical technocrats” who were “barricaded on the fifth floor of City Hall. The people aren’t part of it.” The magazine also said Washington “may be the least powerful Chicago mayor in recent history” and singled out the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) as a “full-fledged disaster.” Politically, Washington’s agenda was “to a great extent, stalled,” primarily because Vrdolyak’s city council majority kept the mayor largely “on the defensive.”

When the bribery scandal broke, Washington’s administration was already besieged. Yet a federal appeals court ruling in August 1984 that black and Hispanic voters were so underrepresented by the city’s existing ward map that the Voting Rights Act was being violated seemed to provide an opening for Washington, because new elections could overturn Vrdolyak’s 29–21 council majority. In June 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the appellate finding, and the case was sent to a district judge who instructed the opposing lawyers to redraw seven wards, all of which were represented by Washington opponents. On December 30, the court ordered new elections in those wards to be held on March 18. In the interim, Washington announced that Judson H. Miner, the forty-four-year-old civil rights lawyer who had litigated the redistricting challenge, would be his new corporation counsel.

But on the Far South Side, the fate of LTV Republic’s East Side steel mill was still in question. In early January, a front-page Wall Street Journal story described the company’s prospects as “dim at best,” and a week later Crain’s Chicago Business published a long report that the Daily Calumet said “sent shock waves through the Southeast Side.” Jerry Kellman told the local paper that LTV should put the mill up for sale, but Maury Richards said that the 1033 union understood that the East Side facility was “losing between $5 million and $8 million every month.”

In mid-January Obama attended a three-day training event in Milwaukee for minority organizers sponsored by the Campaign for Human Development and the Industrial Areas Foundation. Soon after he returned, Chicago headlines confirmed Jerry and Maury’s fears: “LTV Announces 775 Layoffs” plus the closing of the East Side mill’s most modern blast furnace. Kellman told reporters that Illinois officials had “written off the steel industry” and GSU’s Regional Employment Network immediately scheduled four days of skills-assessment interviews at Local 1033’s office in an effort to find new jobs for laid-off workers. Yet everything Frank Lumpkin and his colleagues had experienced in the years since Wisconsin Steel’s sudden closure told them how scarce jobs were on the Far South Side and in the south suburbs.

Loretta Augustine and Yvonne Lloyd encouraged Barack to focus on the sprawling Altgeld Gardens public housing project, just east of where they lived. They introduced him to their pastor at Our Lady of the Gardens, Father Dominic Carmon, and Obama also met with parents whose children attended Our Lady’s small Catholic grade school. He was introduced to Dr. Alma Jones, the feisty principal of Carver Primary School and its adjoining Wheatley Child-Parent Center, virtually all of whose students came from within Altgeld. Jones was immediately impressed with Barack. “Talking to him, he was so much older than he was. It was like talking to your peers rather than somebody the age of your children.” In a community where few people could imagine meaningful change, Jones stood out as an important voice of encouragement for a young organizer venturing into unfamiliar territory.

Despite Altgeld residents’ letters to Mayor Washington complaining about “heavy drug traffic” seven days a week, no city residents were more completely ignored and forgotten than the tenants of Altgeld Gardens. Dr. Gloria Jackson Bacon, who almost single-handedly provided medical care to Altgeld residents for decades, explained that by the 1980s “many of them did not venture outside. Many of them lived almost like insular lives inside of Altgeld.” Bacon recalled others speaking pejoratively of “ ‘those people out there, those people out there,’ and I’d say, ‘These are your people.’ ” Loretta Augustine remembered once taking some Altgeld schoolchildren to the zoo and realizing that “one or two of the kids had never been downtown before.” Loretta referred to Lake Michigan, and “the kid responded, ‘Chicago has a lake?’ ” As Alma Jones told one reporter who visited her school, “Altgeld Gardens is an isolated, enclosed island. We have no stores, no jobs and one traffic signal.”

Barack continued his weekly get-togethers with Asif Agha, but his social life was so meager that Kellman and Mary Bernstein discussed ways to help him meet more people his own age. “He felt to me like a nephew,” Mary remembered, with Barack calling her “Sistah,” and she calling him simply “Obama.” In her eyes, Barack “was always serious,” indeed “driven,” but above all “he was very solitary.” Bernstein recalled that Barack once asked her, “How am I going to get a date?” working in Roseland and spending his evenings at meetings or visiting DCP parishioners. “You don’t want to date any of the women I know,” Mary humorously replied. “They’re all old, and they’re all nuns.”

Loretta Augustine, Yvonne Lloyd, and Nadyne Griffin were all looking out for the young man’s welfare. “I felt very protective, very motherly towards him,” Loretta later told journalist Sasha Abramsky. “We were worried that he wasn’t eating enough,” Yvonne Lloyd recalled. “We were always trying to make him eat more.” Loretta could see that Barack was “very focused” and “very serious,” and more than once she suggested he lighten up. “You shouldn’t be so somber and uptight and serious all the time.” Obama later said he was indeed “very serious about the work that I was trying to do.” Marlene Dillard’s strong interest in jobs had her spending as much time with Barack as anyone, and though she found him “very dynamic” and “very sincere,” his maturity meant she “never looked at him as a son.” But Nadyne Griffin felt just like Loretta did: “He was just like a son to me,” and Tom Kaminski found the church ladies’ solicitude heartwarming: “Everyone wanted to be his mother, everyone thought she was his mother,” and “I felt like an uncle.”

Barack stayed in touch through regular long-distance phone calls with old friends like Hasan Chandoo, Wahid Hamid, and Andy Roth, and in late February, he sent Andy a long letter that was similar to the one he had written Phil Boerner three months earlier:

As I may have told you on the phone, when you’re alone in a new city, the fullness or emptiness of the mailbox can set the tone for the entire day.

Work continues to kick my ass. A lot of responsibility has been dumped on me: I’m to organize an area of about 70,000–100,000 folks and bring the local churches and unions into the action. I confront the standard stuff: the turpitude of established leaders (i.e. aldermen, preachers); the lassitude of the masses; the “we’ve seen middle class folks come in here before and make promises and ain’t nothin’ happened” attitude, which is true; my own inhibitions about playing for power and manipulating folks, even when it’s for what I perceive to be their own good. At least once a day I think about what I’m doing out here, and think about the pleasures of the upwardly mobile (though still liberal Democratic) lifestyle, and consider chucking all this. Fortunately, one of two things invariably snap me out of my brooding: 1) I see such squalor or degradation or corruption going on that I get damned angry and pour the energy into work; or 2) I see a sign of progress—one of my leaders, a shy housewife, dressing down some evasive bureaucrat, or a young man who’s unemployed volunteering to help distribute some flyers—and the small spark will keep me rolling for a whole day or two.

Who would have ever believed that I’d be the sucker who’d believed all that crap we talked about in the Oxy cooler and keep on believing despite all the evidence to the contrary. Speaking of contrary, I’m in such a state for lack of female companionship, but that will require a whole separate exegesis.

A few weeks later, Barack sent a postcard to his brother Roy and his wife Mary, and a longer message to Phil Boerner. He thanked Phil for his encouraging comments about the short story Barack had sent him, but he emphasized what a “discouraging time” he was having:

Unfortunately, I haven’t had much time for writing (stories or letters) lately, what with this work continuing to kick my ass. Experienced some serious discouragement these past three weeks, mainly because of the incredible amount of time to get even the smallest concrete gain. Still, I’m putting my head down and plan to work through my frustrations for at least another year. By that time I should have a fairly good perspective on both the possibilities and limitations of the work.

No one in mid-1980s Chicagoland had anywhere near the degree of success Jerry Kellman did in winning major grants from the Campaign for Human Development, the Woods Fund, the Joyce Foundation, and Tom Joyce’s small but always-pioneering Claretian Social Development Fund. Grant makers regularly visited the organizations they supported, and by early 1986, Jerry had been introducing Barack as a new mainstay in DCP’s Far South Side organizing work. Archdiocesan CHD staffers Ken Brucks and Mary Yu met Barack through Kellman, but the two most influential funders Barack got to know that winter were Woods Fund director Jean Rudd and program officer Ken Rolling. Jean had become Woods’s first staffer five years earlier. Ken, like Greg Galluzzo, was a former Catholic priest who had spent more than half a dozen years in organizing before joining Jean at Woods in 1985. Woods’s commitment to organizing was reaching full flower just as Jerry and then Barack arrived on the scene. As Jean deeply believed, “community organizing is intended to be transformational for ‘ordinary’ people. Through its training and actions, people recognize their worthiness, their legitimacy, their place in a democracy, their power, their voice.” That was the work, and the teaching, that she and Ken wanted to support and champion.

Decades later Jean remembered when Jerry first brought Barack to meet them. “In that first meeting, I was very, very impressed…. He was very, very reflective, very candid … very winningly … humble about what he had to catch up on” about organizing and about Chicago. “I believe I said to my husband, ‘I’ve really met the most amazing person today.’ ” But most of Woods’s actual contact with DCP, CCRC, and other grantees like Madeline Talbott’s ACORN was handled by Ken Rolling, who was even more impressed upon first meeting Barack. “I’ve just met the first African American president,” he told his wife Rochelle Davis that evening. Ken said much the same thing to CHD staffer Sharon Jacobson, who a quarter century later remembered it just as Ken and Rochelle had: “I want you to watch this guy, Sharon. He’s going to be president of the United States one day.”

Jacobson played a leading role in CHD’s grant making in Chicago, and Renee Brereton, based in Washington, was the crucial staffer for allocating national funds. She had directed $42,000 to CCRC in 1984, $40,000 in 1985, and by early 1986, Brereton and Jacobson were overseeing that year’s grant to DCP. She gave DCP’s application 90 out of a possible 100 points, citing as the only shortcoming the confusing organizational overlap between CCRC and DCP. Brereton believed that “DCP is expanding its power base through coalition work with unions, and public housing projects,” and she was impressed with the leadership training Kellman had done with parishioners from DCP’s Catholic churches. “The staff is strong with a commitment to hiring minority staff,” and she recommended at least another $30,000.

Sharon Jacobson oversaw the local Chicago committee that ratified Brereton’s recommendations, and she noted DCP’s intent to develop an employment training and placement program for residents of Altgeld Gardens as well as its desire to improve Far South Side public schools. She wrote that “the large geographical area” DCP sought to cover “is too broad” and threatened to dissipate DCP’s efforts rather than focus them, but DCP was Chicagoland’s “strongest organizing project. In the past year, we have witnessed thorough leadership training, successful multi-issue campaigns, and widespread grassroots community support,” and $33,000 was committed to DCP.

Jacobson also wrote to Brereton that Obama’s attendance at the CHD-IAF minority organizer training in Milwaukee had proven notable; out of twenty attendees, he and one other “had demonstrated the most potential,” leading Jacobson and Mary Yu to recommend that Barack be invited to attend IAF’s premier training event, a ten-day course that took place each July at Mount St. Mary’s College in the Santa Monica Mountains above Los Angeles. CHD would pay Barack’s $500 tuition, $400 room and board, and also cover his travel expenses.

On March 18, special elections were held in the seven redrawn city council wards. Washington’s backers captured two seats from Vrdolyak’s 29–21 majority, but two other pro-Washington candidates fell short of the necessary 50 percent plus 1 and were forced into runoff contests to be held on April 29. Victory was assured for the Washington supporter in the black-majority 15th Ward, but in the 26th Ward, two Puerto Rican candidates, one of whom was sponsored by powerful Vrdolyak ally Richard Mell, faced off amid a cascade of election-misconduct allegations. The Chicago Tribune labeled the 26th Ward contest “the most closely watched election in Chicago history,” with both Washington and Vrdolyak campaigning there two days before the rematch, and Washington’s young election lawyer, Tom Johnson, a 1975 graduate of Harvard Law School, keeping a close eye on the proceedings. When Washington’s ally, Luis Gutierrez, prevailed by a surprisingly comfortable margin of more than 850 votes, the mayor attained a 25–25 city council split, putting him in position to cast a decisive tie-breaking vote—at least until the next regularly scheduled city elections just one year later.

While most of Chicago focused on the Washington vs. Vrdolyak contest, another vote—by United Steelworkers members on a dramatically concessionary new contract with LTV—was building to its own climax on April 4. One week earlier, on March 28—the sixth anniversary of Wisconsin Steel’s closure—Harold Washington met with Frank Lumpkin’s Save Our Jobs Committee. At LTV Republic’s East Side mill, Maury Richards campaigned against the proposed 9 percent reduction in workers’ hourly wage rates and benefits. But even though 1033’s members voted against the new contract 1,254 to 750, well over 60 percent of LTV’s nineteen thousand steelworkers in other states approved it.

As winter turned to spring, DCP began to focus on the forlorn state of the Far South Side’s public parks, a visible example of basic city services being denied to black and Hispanic neighborhoods but not white ones. The city’s parks were overseen by a quasi-independent entity, the Chicago Park District (CPD), which remained a notorious nesting ground for white Democratic ward organization loyalists, even after Washington’s three years in office. Two energetic DCP members—Nadyne Griffin, who had a special interest in Robichaux Park, up at 95th Street, and Eva Sturgies, who lived across the street from Smith Park, at 99th and Princeton—had brought this issue to Obama’s attention. DCP began distributing leaflets in the solidly middle-class blocks around Smith Park, encouraging the community to attend a meeting to address the problem. Aletha Strong Gibson, a college graduate homemaker in her early thirties who lived one block south on Princeton, knew that Smith Park “really wasn’t very safe or conducive for young children” like her six- and four-year-olds. Gibson went to the meeting and spoke up. Afterward Barack “said he’d like to come meet with me about doing some more work on the parks issue,” and following that one-on-one Aletha became a key recruit.

One day early that spring, when Barack was visiting the handsome old Monadnock Building in the downtown Loop, which housed many small progressive organizations, he stopped into the offices of the ten-year-old Friends of the Parks (FOP) and introduced himself to John Owens, a twenty-nine-year-old army veteran who had become FOP’s community planning director a year earlier after finishing a degree in urban geography at Chicago State University. Owens was immediately impressed with Obama. “This guy sounds like he’s president of the country already,” Owens recounted just four years later. “He had an air of authority and a presence that made you want to listen.” Barack talked about the discriminatory treatment accorded Far South Side parks, and Owens explained some of what he knew about “the ins and outs of the Chicago Park District.” Barack had “all kinds of personality,” and “we sort of clicked,” Owens explained.

Barack invited John down to Roseland, and they worked together to start compiling a list of parks the CPD was ignoring: Abbott Park, east of the Dan Ryan Expressway; West Pullman Park, on Princeton Avenue; Carver Park, down in Altgeld Gardens; and the huge Palmer Park, just north of Holy Rosary. One afternoon in Palmer Park, gunshots sounded nearby, and they both ducked behind parked cars. Owen recalled Obama saying, “ ‘You hear that? Whoa!’ ” and remembers thinking, “ ‘Well, he hasn’t been around here very long.’ ”

John and Barack hit it off. Some evenings they went to music clubs together. “I could see he was somebody that I could learn a lot from,” said Owens, and Obama also could learn from Owens, a native of the South Side’s middle-class Chatham neighborhood, about his life experiences as a black man who had grown up in Chicago. Johnnie—as he was often called—quickly became Barack’s first truly close black male friend, at least since the cosmopolitan Eric Moore at Oxy. Before the end of April, Barack asked Johnnie to attend the upcoming July IAF training in Los Angeles, and Owens readily agreed.

In early May, Jerry Kellman’s CCRC got another major grant: $30,000 from the Joyce Foundation to support Mike Kruglik’s organizing work in Chicago’s south suburbs. But Kellman also used his connections within Chicago’s Catholic archdiocese to re-create, in somewhat different form, Tom Joyce and Leo Mahon’s original vision of CCRC as an organization straddling the Illinois–Indiana state line to encompass the entire Calumet industrial region. Jerry had been thinking about restarting work in Indiana even when Barack first arrived, but underlying that was a fundamental truth that Leo and Tom had experienced and that Greg Galluzzo best articulated in explaining that “what was joined together industrially and geographically is not together politically.”