По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

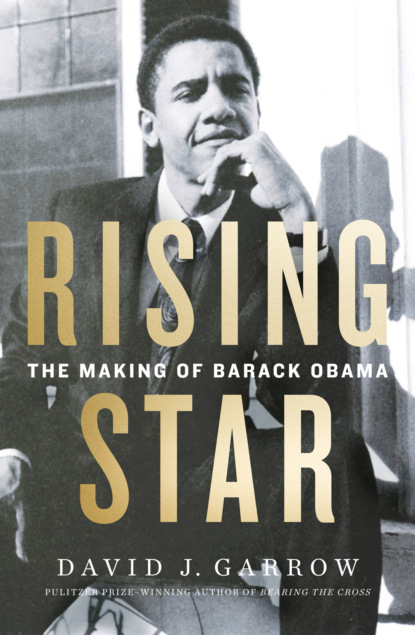

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Rereading this decades later, McNear wondered whether her letters to Barack “were just as pretentious … equally as convolutedly long and laborious.” Barack wrote, “I enjoyed your letter. I like the way you use words,” and then proceeded to a long disquisition on the concept of resistance against a “bankrupt” and “distorted system…. But people are busy keeping mouths fed and surroundings intact, and it is left to the obsessed ones like us to make the alternatives more tangible … so that resistance and destruction arrive in the form of creation.” He then paused to say “excuse the sermons,” but “I also have thought about us and conclude that I like what we have…. Perhaps what I’ve been after is a correspondence, a union, yes—but never exclusive, cocoon-like, ingrown. Rather something outwards, a point of extension.”

With graduation approaching, he had more mundane issues to discuss. “I’ve been sending out letters to development and social services agencies, as well as a few publications, so I should find out in the next few months what I have to work with next year. Classes are the average fare. A class called Novel and Ideology has an interesting reading list covering several of the things we spoke of” when Barack was in Los Angeles. “Of what I’ve read so far I recommend Marxism and Literature by Raymond Williams. A lot of it is simplification, but it generally has a pretty good aim at some Marxist applications of cultural study. Anyway, it might be a good point of departure for further haranguing between us.”

Obama then ends the letter, but the next day he added a long postscript that began by mentioning homeless panhandlers he often saw. “I play with words and work pretty patterns in my head, but the hole is dark and deep below, immeasurably deep. Know that it’s always there, rats nibbling at the foundations, and it can set me to tremble.” Then he thought to respond to something Alex had said about T. S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land and told her to read Eliot’s 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” as well as his Four Quartets. “Remember how I said there’s a certain brand of conservatism I respect more than bourgeois liberalism.” Barack finally concluded by saying, “I can’t mobilize my thoughts right now, so … I leave you to piece together this jumble.”

The label “jumble” could also apply to an article Barack submitted to Sundial, a weekly Columbia student newsmagazine. Just prior to its publication, he wrote to Phil Boerner in Arkansas and mentioned he had “been sending out some letters of inquiry to some social service organizations and will also be making up a resume (no comment) soon. I’ve also written an article for the Sundial purely for calculated reasons of beefing up the thing. No keeping your hands clean, eh.”

The article, titled “Breaking the War Mentality,” began by asserting that “The more sensitive among us struggle to extrapolate experiences of war from our everyday experience, discussing the latest mortality statistics from Guatemala, sensitizing ourselves to our parents’ wartime memories, or incorporating into our frameworks of reality as depicted by a Mailer or a Coppola. But the taste of war—the sounds and chill, the dead bodies, are remote and far removed. We know that wars have occurred, will occur, are occurring, but bringing such experiences down into our hearts, and taking continual, tangible steps to prevent war, becomes a difficult task.”

Following that introduction, Obama cited what he called “the growing threat of war” while profiling the first of two campus antinuclear groups, Arms Race Alternatives. “Generally, the narrow focus of the Freeze movement as well as academic discussions of first versus second strike capabilities, suit the military-industrial interests, as they continue adding to their billion dollar erector sets,” he opined. “One is forced to wonder whether disarmament or arms control issues, severed from economic and political issues, might be another instance of focusing on the symptoms of a problem instead of the disease itself.”

Obama also referenced a recently adopted federal law, set to take effect on July 1, that required every male recipient of federal student aid to demonstrate that he had registered for the draft. Some voices were calling for noncompliance, and Obama observed that “an estimated half-million non-registrants can definitely be a powerful signal” that could herald a “future mobilization against the relentless, often silent spread of militarism in the country.” He then described the second campus group, Students Against Militarism. Declaring that “perhaps the essential goodness of humanity is an arguable proposition,” Barack contended that “the most pervasive malady of the collegiate system specifically, and the American experience generally, is that elaborate patterns of knowledge and theory have been disembodied from individual choices and government policy.” He ended by commending both groups, saying that by trying to “enhance the possibility of a decent world, they may help deprive us of a spectacular experience—that of war.”

New Yorker editor David Remnick would later characterize Obama’s article as “muddled,” but when it returned to public view twenty-six years after it was first published, it generated astonishingly little discussion of what it said about the political views Obama had held on the cusp of his graduation from college. In his letter to Phil, Barack belittled how “school is just making the same motions, long stretches of numbness punctuated with the occasional insight.” Referencing their disappointing fall semester course, he complained that “Said still didn’t have the grades out for his class until a month into the term, and he cancelled his second term class, so we should feel justified in labelling him a flake.”

As he had in his earlier letter to Alex, Barack singled out Davis’s Ideology and the Novel as an “interesting” course, one “where I make cutting remarks to bourgeois English majors and can get away with it.” But overall, “nothing significant, Philip. Life rolls on, and I feel a growing competence and maturity.” After insulting what he called Phil’s “sojourn to Buttfuck, Arkansas,” Barack closed by saying, “Will get back to you when I know my location for next year.”

In Boerner’s absence, Barack had been spending time with old Oxy friend Andy Roth, who was working at the John Wiley publishing house. On Friday, April 1, he and Andy attended the first day of the inaugural Socialist Scholars Conference, held at the famous Cooper Union. Roth remembered them both attending an “interesting” talk by sociologist Bogdan Denitch, one of the most committed leaders of Democratic Socialists of America. But rather than attend the conference’s second day, Barack wrote another long letter to Alex McNear. “There are moments of uncertainty in everything that I believe; it’s that very uncertainty that keeps my head alive,” Barack explained. “In pursuit of such hopes, I attended a socialist scholars conference yesterday with Andy. A generally collegiate affair with a lot of vague discourse and bombast. Still, I was pleasantly surprised at the large turnout, and the flashes of insight and seriousness amongst the participants. As I told Andy, one gets the feeling that the stage is being set, that conduits of word and spirit are being layed across diverse minds—feminists, black nationalists, romantics. What remains to be had is a script, a crystallization of events. Until that time a pervasive mood of unreality hangs over such events, a mood that you can see the people fighting against in their eyes, their tone.”

A decade later Obama wrote passingly but imprecisely about “the socialist conferences I sometimes attended at Cooper Union.” His erroneous use of the plural gave future critics fodder to imagine that the “impact of these conferences on Obama was immense” and that listening to Denitch and similar speakers had “turned out to be Obama’s life-defining experience,” a notion that his letter the very next day to Alex utterly rebuts.

At the outset of that letter, Barack wrote of “churning out assignments” on “state communism” and “the international monetary system” before pausing to reflect on “the wilderness we call life” while smoking and drinking scotch. He reported that he had given his papers to “an elderly woman with a hair-lip and hoarse voice” for typing. This lady was Miss Diane Dee, who was a famous figure around Columbia for decades. A later New York Times profile said “her advertising flyers” are “indigenous to campus walls,” but that her “unkempt hair” and “tired face” made her seem “half-crazed.” One 1983 Columbia graduate believed “she was crazy,” and Gerald Feinberg’s son Jeremy recalled her as “a colorful character—someone I’d expect to appear in a conspiracy theory movie or a Michael Moore film, or both.”

Barack told Alex that Miss Dee was someone “upon whom my graduation depends,” and he was starting to panic because she “has missed two deadlines so far and now seems to have disappeared … no one has answered the phone at her apartment for four days.” He worried that “she’s a mad woman who lures unsuspecting undergraduate papers into her home and then burns them, or uses them to line the bottom of the goldfinch cage.” Following his description of the Socialist Scholars Conference, Barack told Alex that a “sense of unreality describes my position of late. I feel sunk in that long corridor between old values, actions, modes of thought, and those that I seek, that I work towards … this ambivalence is acted out in my non-decision as yet about next year” following graduation.

Three days after Obama wrote that letter, Columbia’s Coalition for a Free South Africa, in tandem with Students for a Democratic Campus, held a divestment rally outside Low Library, Columbia’s administration building. Student leaders Danny Armstrong and Barbara Ransby had been pressing the issue for months, and the scheduling of a university board of trustees meeting on the fifteenth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination offered an occasion for an afternoon protest. Barack convinced his largely apolitical apartment mate Sohale Siddiqi to attend the rally with him. But Siddiqi thought that compared to the black New Yorkers Siddiqi knew from the restaurant where he worked, “Barack didn’t seem like one of them.” Obama “was soft-spoken and gentle” and used “clean language.” Indeed, “I didn’t consider him American,” never mind African American. Siddiqi believed Barack “seemed like an international individual.”

Siddiqi recalls having witnessed an intensifying change in Barack over the preceding eight months. “He had kind of gone into a bit of a shell and wasn’t as talkative or outgoing as in his earlier days,” Sohale said. When Barack did speak, “he’d give me lectures” about “the plight of the poor” and downtrodden. “He seemed very troubled by it,” and “I would ask him why he was so serious.” Sohale’s interest in drinking, picking up women, and enjoying cocaine held little appeal for the newly abstemious Barack. “He took himself too seriously,” Sohale felt, and “I would find him ponderous and dull and lecturing.”

The April 4 rally drew a disappointing crowd of about a hundred, but afterward a core group of about fifteen student coalition members kept up a 9:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M. weekday vigil to highlight Columbia’s refusal to divest. Barack was not among them, and few of Columbia and Barnard’s black undergraduates from 1981 to 1983 have any recollection of Barack Obama. Coalition leader Danny Armstrong said, “I recall seeing Obama on campus” but never interacted with him. Barbara Ransby, a graduate student who managed the coalition’s contact list and chaired most of its meetings, had “utterly no recollection of Obama.” Verna Bigger Myers, president of the Black Students’ Organization (BSO) in 1981–82, remembered that on a campus with so few minority undergraduates, “all the black people see the other black people” even if they did not really know them. Myers’s close friend Janis Hardiman, who a decade later would be Obama’s sister-in-law, remembered Barack as “sort of a phantom who just kind of walked into” BSO meetings but “did not have an active role” or participate in any the group’s activities.

Wayne Weddington, a junior in 1982–83, remembers seeing Obama at BSO meetings, and Darwin Malloy, a year ahead of Obama, recalled meeting him in the cafeteria in John Jay Hall but agrees that “most people would only remember him as a familiar face.” Malloy believed his friend Gerrard Bushell “probably had more interaction with him than anyone,” but Bushell said he “would see him periodically” and “remember him by face” but no more.

Obama would dramatically exaggerate his involvement in Columbia’s divestment activism on several occasions, telling one interviewer that “I was a leader on these issues both at Occidental and at Columbia.” Talking about his two years there to a second questioner, Obama asserted that “while I was on campus, I was very active in a number of student movements” and particularly “I was very active in the divestment movement on campus.” Several years later, on his first visit to South Africa, Obama declared that “I became deeply involved with the divestment movement” and “I remember meeting with a group of ANC leaders” or at least “ANC members one day in New York City.” There are no contemporary records or other participants’ memories that attest to any such encounter.

Columbia’s African American students were also acutely aware that the Faculty of Arts and Sciences included only four black professors. By far the most visible was the handsome, bow-tie-wearing Charles V. Hamilton, best known as the coauthor of Stokely Carmichael’s 1967 book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. Hamilton had arrived at Columbia in 1969, was named to a chaired professorship two years later, and in 1982 was the recipient of the university’s award for excellence in undergraduate teaching. “Everyone knew who Hamilton was,” one 1983 political science major recalled. In addition, as one younger colleague said, “Hamilton was always approachable. The hallway outside his office at the southwest end of the SIPA building was often filled with students.”

But, thirty years later, when asked for the first time whether one particular 1983 African American poli sci major had ever taken one of his courses or sought his counsel, Hamilton said, “I didn’t know him at all.” Black history professor Hollis R. Lynch also has no recollection of Obama, nor does the entire roster of senior political science faculty. Even within Obama’s particular area of concentration, international relations, neither Warner Schilling, Roger Hilsman, Zbigniew Brzezinski, nor John G. Ruggie remembers him. “Never laid eyes on him,” Ruggie said. Indeed, apart from young Michael Baron, “nobody really knew him,” one thirty-year veteran of the department reported. Obama would earn an A on the senior paper he wrote for Baron. It analyzed the decision-making during the arms-reductions negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union. But Baron would discard the paper years before the world beyond Morningside Heights would yearn to read it.

One week before the end of classes, Obama wrote another long letter to Alex McNear, who had taken leave from Oxy for spring term and was working in Pasadena. Citing “the method of negation” and “comparing what is to what might be,” Barack for a second time referred to something he had said in an earlier letter. Then he referenced their time in L.A. four months earlier: “a young black man” and “a young white woman” “that night in Wahid’s apartment in a timeless reddened room.” He also said his job prospect letters had not produced any firm leads, and that “I feel like forgetting the whole enterprise and taking you with me to Bali or Hawaii to live.” McNear years later recalled no actual invitation, and then Barack’s letter descended into vague declarations. “I am often cruel, and my mind will flash on the screen scenes of violence or petty malevolence or betrayal on my part.” McNear had no idea what he was referencing, and then Barack asked, “am I a blathering chump to you right now, or do you glean some sense from this mess?”

Barack continued on similarly, invoking “the necessary illusion that my struggles are the struggles of the first man, the river is the original river … What else? I enjoy my body, even when it frightens or disgusts me … I recall you saying that you still believe the mind is stronger than the body. A dangerous distinction, Alex, a vestige of western thought.” Rereading that passage years later, McNear felt it was “condescending.” Finally leaving his “river” for firmer ground, Barack wrote that it “looks like I will take a two month vacation to Indonesia and Hawaii next month. Will be stopping in L.A. either on the way over or back, if I come back. Will get in touch before I leave … Love, Barack.”

Photos from sometime around Columbia’s May 17 commencement show that Stan and Madelyn Dunham made the long trip from Honolulu to New York City to see their grandson, although Barack years later explained that “I actually didn’t go to my own graduation ceremony” since “my parents couldn’t come.” Soon after, Barack flew from New York to Los Angeles, where he stayed for several days with Alex McNear in her apartment. “We had this kind of picnic lunch on the floor of my living room,” Alex recalled. Even with Barack’s invocation of “black man” and “white woman” in his letter, blackness and racial identity “really was not something that he talked about a lot,” she remembered. “It barely ever came up.” Reflecting on that visit years later, “I felt he was less engaged” than he had been four months earlier. She thought there was “an enigmatic quality” to Obama, and “most of this relationship really revolved around these letters,” irrespective of their clarity.

Obama then flew to Singapore, where he spent five days with Hasan Chandoo and his family, a visit that coincided with Asad Jumabhoy’s appearance in the championship polo match of the Southeast Asian Games. In a letter to Alex, Barack wrote that Hasan “seemed fine, if more subdued than you remember him.” Barack found Singapore “an incongruous place … slick and modern and ordered, one vast supermarket surrounded by ocean and forest and the poverty of ages. Mostly peopled with businessmen from the states, Japan, Hong Kong as well as various family elites of Southeast Asia.” Hasan, Asad, and Barack went to a discotheque or two, but Barack wrote Alex that he remained largely silent when Hasan talked about the choices he was facing, “primarily to leave a space for our friendship should he move into the business world permanently.”

From Singapore, Barack flew to Indonesia and stayed at his mother’s comfortable Ford Foundation home in South Jakarta. Anthropologist friends of Ann’s often stayed there too, and among the guests that summer was a Rutgers University graduate student, Tim Jessup. Ann’s work at Ford had kept her busy throughout 1982 and into 1983. She had written a brief paper entitled “Civil Rights of Working Indonesian Women” and delivered a lecture entitled “The Effects of Industrialization on Women Workers in Indonesia” to the Indonesian Society of Development. In mid-May, she had spent four days in Kenya, of all places, less than six months after her first husband’s death, but Ann never spoke about this trip to friends.

When she wrote a long priorities analysis for Ford’s continued work in Indonesia, Ann recommended that they “focus on a relatively new program area, women and employment,” and particularly “the role of poor women as workers and income-earners.” The ideal grantee would be “a non-governmental social action group founded by women for women,” but she rued “the general weakness and lack of leadership within the women’s movement in Indonesia.” As Alice Dewey and a colleague wrote years later about Ann, “Java”—Indonesia’s principal island—“was as much her home”—if not far more—“as Honolulu.”

In his letter to Alex, Barack wrote that “my mother and sister are doing well,” but with Ann “the struggling seems out of her, and the colonial residue of her life style—the servants, the shopping at the American supermarket, the office politics of the international agencies—throw up continual contradictions to the professed aims of her work.” Barack was writing not from Jakarta but “from a screened porch somewhere on the northwest tip of Java.” He confessed that “I can’t speak the language” and that Indonesians treated him “with a mixture of puzzlement, deference and scorn because I’m American, my money and my plane ticket back to the U.S. overriding my blackness,” as Obama was now old enough to perceive how many Indonesians loathed his skin color. But he closed by saying, “I feel good, engaged, the mystery of reality, the reality of mystery filling me up.”

From that same porch, sitting “in my sarong, sipping strong coffee and drawing on a clove cigarette, watching the heavy dusk close over the paddy terraces of Java,” Obama also wrote a postcard to Phil Boerner. “Very kick back, so far away from the madness. I’m halfway through my vacation, but still feel the tug of that tense existence…. Right now, my plans are uncertain; most probably I will go back” to New York City “after a month or two in Hawaii.” In early July, he and apparently also his almost thirteen-year-old sister Maya flew from Jakarta to Honolulu. Only then did he actually mail his letter to Alex, writing on the back of the envelope that “with the postal system in Indonesia we’d be dead and gone before it arrived.”

Barack did not write to Alex again until September 1, and by then, his tone was dramatically cooler, almost palpably angry. Reacting apparently to something Alex had written to him, Barack wrote that “you are correct when you say that initially you were to me nothing more than a lovely wraith I had shaped to fit my needs, and I fought against this and you taught me yourself and I feel I showed progress eagerly, like a repentant student coming home with high marks. All this I have admitted to you in my letters—go back and reread some.” Indeed rereading them three decades later, McNear reacted immediately to Obama’s self-characterization: “student? … They all seem more like the professor,” and that he was writing lectures. She said they are “not romance letters at all.”

Then Barack’s tone turned almost hostile, or ugly. “When I see you, the palpitations of the heart don’t boil to the surface,” he told Alex. “I care for you as yourself, nothing less but also nothing more. Does this anger you?” Again, “Does this anger you? When I sit down to write I no longer feel the need to bleed for brilliance on the page.” Years later, McNear does not know why Obama’s attitude had changed so starkly during these two summer months in Honolulu. “Here was someone who I felt that I cared a lot about. I loved him, I enjoyed seeing him,” but his interest in her had somehow waned. “I trust the strength of our relationship enough that I can show myself with rollers in my hair,” Barack wrote before again asking, “Does this anger you, Alex? It shouldn’t. Friends feel weary sometimes. When I said that we will ever want what we can’t have, I missed nothing.” He referenced “the bitterness that plagues my grandparents,” a comment McNear later said contradicted everything else she recalled him saying about them.

“I seek something in myself using the clues of this wind, that boy, my mother, your pain, perhaps the world,” Barack wrote, returning to his prior form. “Yes, this requires a monumental arrogance, and of late I feel it whittling away. If my arrogance (which has always been confessed—run back the tapes) angers you, then my last letter, our last meeting, should douse it. It is precisely the arrogance, the sense of destiny, that has been absent. I no longer feel compelled to try to shackle you in my abstruse dreams.” Addressing something Alex apparently had written, “When you doubt my honesty, you give me more credit in the past than I deserve. As though I calculated to deceive you in some way, represented myself as something I didn’t believe I was. You judge me badly; I think I have been as upfront about my doubts and demons as I knew how to be.”

Barack’s defensiveness was more than evident. “And when you question my sincerity (a word much abused, like democracy and justice) … you haven’t been listening very well when I spoke of myself.” He closed the letter by saying, “my plans are still uncertain right now” and that he had been “typing up letters to perspective [sic] employers for the last two hours with maniacal tidiness.” But “unless a job of some interest pops up soon, I’ll be flying back to New York at the end of this month” and will stop in Los Angeles. Almost three months would pass before Barack wrote her again.

Sometime in the first half of October, Obama left Honolulu for New York. If he stopped in Los Angeles, he did not contact Alex. Arriving in New York, he stayed for one week with Wahid Hamid, who now had a job with Siemens, in a second-floor apartment in suburban Long Island. He then returned to the familiar confines of 339 East 94th Street #6A, where he crashed on the living room couch of Sohale and his new roommate. “I felt a slight longing to move back into the known quantity,” Barack wrote Alex a month later, but “the howling and drinking and haze of my short stay smothered any productive impulses I may have had, so that moving to a new situation came easily.”

Obama next found a room in a three-bedroom apartment at 622 West 114th Street #43. He told Alex that out on Long Island he had spent his days “in seclusion sorting through various letters and timetables, spying on the damp, A-frame life of suburbia, wandering along the shoulders of roads” that lacked sidewalks. Wahid was “absorbed with his work” but retains “his integrity and curiosity for the strangeness of life, and I left his apartment certain that our friendship can straddle the divide of our different choices.” His time at Sohale’s had presented “cash flow problems” that had hindered getting his “job hunt in motion” as one week he was unable to pay for postage to mail out résumés, and “the next I have to bounce a check to rent a typewriter.” To remedy that shortcoming,

I took a one week stint supervising a project to transfer the files of the Manhattan Fire Department into a new facility, a fascinating experience affording me a taste of the grinding toil of low-rung white collar jobs, as well as the ambivalent relationships established between employers, employees, and personnel agencies with their shifting mix of loyalty, manipulation, abuses of power, rebellion and concession. The workers, an odd assortment of lower income kids, elderly women and unemployed liberal arts majors, struck me as some of the best people I’ve met; as the 12 hour shifts (uh-huh) wore on I watched much subtle straightforward contact being made and greater political perception than I had expected (although rarely framed in political terms). I felt a greater affinity to the blacks and Latinos there (who predictably comprised about three-fourths of the workforce there) than I had felt in a long time, and it strengthened me in some important way. My role as supervisor clouded the relationship between myself and them, however, since I felt that the company was using it as leverage to extract cooperation from the people for sometimes unreasonable demands. I tapped a feeling of community that comes in people acting in concert on a certain process; yet I felt frustrated that the project was imposed from above, structured according to bids and contracts and the bookkeeper, without lasting benefit beyond the pint-sized paychecks for the workers involved.

At 622 West 114th, “I occupy a room in the apartment of a woman in her late twenties,” Dawn Reilly, who was “a dance instructor and taxi cab driver. The arrangement is fine for now. The place is large and warm, we see little of each other and when we do we maintain a pretty good patter. I suspect I may move if and when the opportunity for a lease arises, though, simply because the rent is a bit steep, and I feel obliged to keep the kitchen clean and air out the living room when I smoke.” Since salaries in “community organizations are too low to survive on right now … I hope to work in some more conventional capacity for a year, allowing me to store up enough nuts to pursue those interests the next.”

He closed by remarking that “I feel lonely yet surefooted, and hope all goes well for you … Get in touch when you get a chance, or impulse. Love, Barack.” A month earlier, Alex had begun seeing a new young man, and she believes she did not reply. Six months would pass before she next contacted Obama.

Within days of mailing that letter, Barack saw a posting at the career office of Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs for a job at Business International Corporation, an international finance information and research firm founded in 1956 that published numerous analytical and data service periodicals from its offices on the seventh floor of One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, on the west side of Second Avenue between 47th and 48th Streets in midtown Manhattan. The job had been posted by BI’s Cathy Lazere, a 1974 graduate of Yale who had earned an M.B.A. at New York University before joining BI’s Global Finance Division eight months earlier, in February 1983. Lazere was responsible for a bimonthly newsletter entitled Financing Foreign Operations—Interest Rate & Foreign Exchange Rate Updater, a four- or five-page publication that cost $900 to subscribe to annually but helped BI pull in a tidy profit as one of a bundle of services that major corporations purchased through individual client programs. In November Lazere was being promoted by division vice president Lou Celi to oversee both FFO and its sister reference publication, Investing, Licensing & Trading (ILT), which was edited by Beth Noymer, a 1983 graduate of Franklin & Marshall College who had joined BI just four months earlier.

Lazere had a roommate at Yale who was from Hawaii and had graduated from Punahou, so when a résumé arrived listing that as well as Columbia, Lazere invited him for an interview. Obama impressed her as “articulate and bright,” and knowing he had attended Punahou, “I assumed he came from a privileged background.” Cathy introduced Barack to Beth Noymer and telephoned Lou Celi to get his approval before offering Barack the position. Obama’s salary would be about $18,500—a respectable sum for a newly minted B.A. in 1983—and he would be expected to write for the finance unit’s flagship newsletter, Business International Money Report (BIMR), as well as to do the research and copyediting necessary to churn out each issue of FFO. A few years later Barack would tell a questioner that he took the job at BI because “I wanted to know how money worked.”

More than three dozen correspondents all around the world submitted the data and material that Lou Celi’s unit sliced and diced to produce their multiple publications. FFO’s content, as its title made clear, was both arcane and impenetrable. Celi’s top deputy and sidekick, Barry Rutizer, had started out at BI doing FFO, and he said, “I couldn’t even read it when I was editing it.” Cathy Lazere agreed. “I was certainly bored when I was editing that stuff.” At the time of Obama’s arrival, issues of FFO consisted of lengthy country-by-country lists of exchange rates accompanied by brief comments and a summary table of “Foreign Exchange Rates of Major Currencies.” Barack had his own office, but the composition and production of BI’s publications took place on a central word processing system that relied upon Wang terminals scattered around the office rather than individually assigned. As a result “we sort of duked it out over Wang time,” Beth Noymer said, with almost everyone regularly moving around the roughly sixty-person office. “The Wangs were a big part of our lives,” Celi’s assistant Lisa Shachtman Hennessey recalled, and “every ten minutes” someone seemed to call out from the bullpen area that “the Wangs are down.” Smoking was more than allowed—“there were ashtrays everywhere,” Lisa remembered—and Obama regularly smoked Marlboros while editing manuscript copy by hand. “There was almost no way to get all your work done between nine and five,” Beth explained, especially on days when the final content had to be sent down to the print shop that BI veteran Peggy Mendelow oversaw in the building’s basement.

Much of BI’s information gathering required telephoning various midlevel officials at corporations and banks. When calls were returned, BI’s switchboard operator announced the call over an office-wide paging system if someone was not at their desk. Brenda Vinson, an African American woman in her late thirties, worked in the library and often covered the switchboard. Obama was the first black college graduate to work at BI, and his unfamiliar first name was a challenge to pronounce. Vinson remembers Barack as “very personable” toward her and her cousin, who were BI’s only other black employees; a Puerto Rican father and son staffed BI’s mailroom. There was a good bit of socializing among the young professionals who worked at BI. A nearby Irish pub was one regular destination, and Beth Noymer later described BI’s office culture as “a hotbed of young singles.”

Obama did not socialize with his BI workmates, but sometime prior to New Year’s Eve, his friend Andy Roth invited him to a party that Andy’s brother Jon was hosting in their sixth-floor apartment at 240 East 13th Street. Jon worked at Chanticleer Press, a publisher that helped produce National Audubon Society guides, and other invitees included Genevieve Cook, a twenty-five-year-old Swarthmore College graduate who had worked at Chanticleer before beginning coursework toward a master’s degree in early childhood education at Bank Street College of Education. She was born in 1958 to parents who were Australian: Helen Ibbitson, the daughter of a Melbourne banker, and Michael J. Cook, a conservative diplomat who would go on to head up Australia’s top intelligence agency before serving for four years as ambassador to the United States. Her parents had divorced when Genevieve was ten years old, and Helen then married Philip C. Jessup Jr., an American lawyer and executive whose International Nickel Company post had him and Helen living in Jakarta during the 1970s. Genevieve attended multiple boarding schools in the U.S. before graduating from the Emma Willard School near Albany, New York. While she was at Swarthmore, her mother and stepfather Phil had moved from Jakarta to New York, and by late 1983 Genevieve was temporarily living in their spacious apartment on Park Avenue just below 90th Street after breaking up with a Swarthmore boyfriend with whom she had lived in Manhattan’s East Village while student teaching that year at the Brooklyn Friends School.

Her four years at Swarthmore were the first time Genevieve attended the same school for more than two years, and it was her first time in one country for more than three straight. “At Swarthmore, I was very drawn to … the drug oriented counterculture” and “its ritualized pot smoking,” she wrote in her impressive 1981 senior anthropology thesis, “Dancing in Doorways.” For the thesis, she interviewed fifteen fellow students who were also the children of expatriates, “people who spent their lives from the time they were born moving around from country to country, who are not members of any one culture, who come from nowhere in particular, and who do not really belong anywhere. You will always know them when you meet them.”

At the Roth brothers’ party, Genevieve did know one when she met one. She and Obama struck up a conversation that lasted several hours after they discovered their mutual ties to Indonesia and expatriate similarities. “I remember being very engaged, and just talking nonstop,” she later wrote. “We both had this feeling of how bizarre and exciting it was that we’d both grown up in Indonesia, and we felt we very much had a worldview in common.” Barack was in no way aggressive. “If anything, he struck me as diffident … although also at ease with himself” and “clearly interested in pursuing this conversation with me.” She found him “just really interesting, intellectually,” and she later reflected that “the thing that connected us is that we both came from nowhere—we really didn’t belong.” Before the night was out, he handed her a small scrap of paper—“Barack Obama 866-8172 622 W. 114th #43”—that she still retains thirty years later. After a phone call the next week, she agreed to meet him at his apartment for dinner, where Barack cooked for the two of them. “Then we went and talked in his bedroom. And then I spent the night. It all felt very inevitable,” she wrote in a private memoir.

That evening stood in sharp contrast to Genevieve’s rejection of a dinner host seven months earlier. That spring she had taken a course at Bank Street that involved having the students share recipes with their classmates. Three decades later Genevieve still had the “Floating Island Pudding” she shared as well as “Zayd’s Catsup,” a contribution from a thirty-seven-year-old classmate. At the end of the semester, that classmate invited her to dinner at his apartment at 520 West 123rd Street #5W. Five-year-old Zayd and his two-year-old brother Malik were asleep, as was Chesa, another almost two-year-old member of the household, whose mother and father were both in prison.

Genevieve was initially surprised that the only food her host had for dinner was grapes, but it quickly became clear what he wanted for dessert. He explained that he was in an open relationship; he and his partner had been leading figures a decade earlier in a group whose slogans included “Smash Monogamy!” His partner was not coming home that night; indeed she was residing involuntarily at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in lower Manhattan, where she would remain for another six months. “He gave getting me into bed quite a good go,” Genevieve recalled, but with a thirteen-year age difference between them, he “seemed awfully old to me!” Her host “was quite miffed that I was not impressed by his ‘status’ ” as a notorious former radical, albeit one whose FBI “Wanted” poster made him appear to have just fallen out of bed rather than striving to get into one. He “backed off when I wasn’t interested,” and Genevieve’s rebuff may have had a greater impact than she realized.

Four months later a federal judge gave her host’s partner a weekend furlough so the two former anti-monogamy advocates could marry, and two months after that, the judge allowed her to return to 520 West 123rd Street on a Christmas furlough. Four days after New Year’s, the judge granted a motion to vacate the contempt citation that had kept Bernardine Dohrn jailed since May 19, and she was free to remain with her two sons and now husband, Bill Ayers. As Genevieve would pluperfectly capture the essence of the story, sometimes indeed the “truth is so much stranger than fiction!”

On Monday, January 9, Genevieve spent a second night with Barack on 114th Street, and the next day wrote in her journal, “I have not experienced the kind of intellectual stimulation Barack offers me since I left college.” She expressed similar feelings in a letter she wrote to him but did not mail, a letter she still had three decades later. “You are the first person I’ve met since being in college who has in some way engaged me in a process of self-intellectual questioning. It is a shock to recognize that my engagement with Bank St., education, friends I’ve made through Bank St. & teaching & the kind of process I’ve touted, of teaching forcing you to be self-evaluative, has all been ‘professional.’ ”

Over the next four weeks, Genevieve continued to record in her journal her reactions to Barack. Intercourse was pleasant, and in bed “he neither came off as experienced or inexperienced,” she later recalled. “Sexually he really wasn’t very imaginative, but he was comfortable. He was no kind of shrinking ‘Can’t handle it. This is invasive’ or ‘I’m timid’ in any way; he was quite earthy.” In one late January entry, she wondered “how is he so old already, at the age of 22?” and she wrote two poems for Barack, one teasing him by way of implicit comparison to the mythical Orion. The second, alphabetical in form, progressed from “B. That’s for you” to “F’s for all the fucking that we do” to “L I love you … O is too.”

Obama spoke excitedly about Genevieve during one phone conversation with Hasan Chandoo in London, yet in a “rather mumbled” one with his mother Ann in Jakarta he made no mention of Genevieve but talked about BI. “Barry,” as Ann called him in a letter to Alice Dewey, “is working in New York this year, saving his pennies so he can travel next year … he works for a consulting organization that writes reports on request about social, political and economic conditions in third world countries. He calls it ‘working for the enemy’ because some of the reports are written for commercial firms that want to invest in those countries. He seems to be learning a lot about the realities of international finance and politics, however, and I think that information will stand him in good stead in the future.”