По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

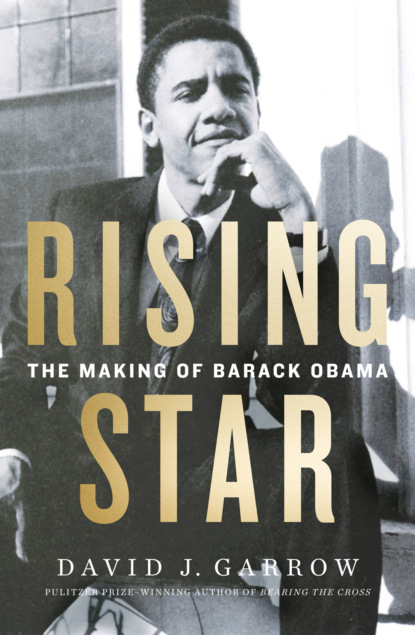

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The April 4, 1979, execution of former Pakistani president Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who had been deposed two years earlier in a military coup led by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, had greatly intensified Pakistan’s political turmoil and also caught the attention of several Oxy students. Hasan Chandoo had grown up in a politically aware family, and his mother was a distant relation of Pakistan’s revered founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Chandoo’s girlfriend Margot Mifflin, a sophomore who had started an Oxy field hockey team that Hasan volunteered to coach because he found its star player so attractive, knew best how “passionate” Chandoo’s hatred was for the military dictatorship. “I think I recall Hasan spray painting ‘Death to Zia’ somewhere on campus,” she later recounted. Pakistan was a regular topic of discussion in the Haines Annex alcove and even more so in the Freeman student union snack bar that everyone called the Cooler. Open during the day and then again from 8:00 P.M. to 11:30 P.M., the Cooler was the favorite hangout for Oxy’s most politically conscious students, like Caroline Boss, as well as for self-identified literati like Chuck Jensvold, a junior transfer from a community college who was five years older than his classmates.

By spring term 1980, Barry was an evening regular there too. “Obama always seemed to be in there,” smoking and drinking coffee, “just jousting back and forth with whoever would come,” Eric Moore remembered. One day when Barry walked into the Cooler, Caroline Boss from his political science class introduced him to Susan Keselenko’s roommate, junior Lisa Jack, an aspiring portrait photographer. Lisa already had been told that Barry was this “hot” guy, and seeing that he indeed was “really cute,” she asked if she could take a roll of photos of him. Barry readily agreed, and a few days later he walked over to Lisa and Susan’s nearby apartment. Wearing jeans, a dress shirt, and a leather bomber jacket with a fur collar, Barry also wore a ring on his left index finger, a digital watch on his left wrist, and a bushy Afro that was in need of a drive to South Central. Jack’s first fifteen photos captured Obama smiling and smoking while sitting on a simple couch. Then Obama doffed the jacket, rolled up his shirtsleeves, and put on a colorful Panama hat he had brought along. Jack shot eighteen pictures of Obama wearing the hat, then a final three of him bareheaded. Throughout them all, Obama looked without question happy, carefree, and very young for eighteen years of age.

Over a quarter century later, when Jack discovered her old negatives and sold publication rights for some of them to Time magazine, former Oxy classmates who had clear memories of Obama’s daily appearance during those years said the guy in the photos bore little resemblance to how they remembered him. “That’s not how he looked or dressed,” Eric Moore commented. John Boyer was even more succinct: “That’s not him.”

After spring term exams, Barry spent some of the summer living with Vinai Thummalapally in the apartment Vinai and Hasan Chandoo had shared. Barry returned to Hawaii for at least part of the summer, and on July 29 he registered for the reinstituted military draft at a Honolulu post office. His almost ten-year-old sister Maya had landed in Hawaii twelve days earlier; their mother, Ann, apparently had arrived some weeks previously, because on June 15, a local attorney had filed her signed divorce complaint against Lolo in the same court where sixteen years earlier Ann had divorced Barry’s biological father. Ann’s filing said that “the marriage is irretrievably broken”; in a supporting document she stated that “husband has not contributed to support of wife and children since 1974,” was “living with another woman” and “wishes to remarry.” Ann reported that she was living “in 4-bedroom house provided by” DAI, her employer, and that she had “2 full-time live-in domestics.” The decree she and Lolo signed stated that Lolo “shall not be required to provide for the support, maintenance, and education” of Maya.

Ann and Maya were again staying with Alice Dewey, but Barry was back with his grandparents in their apartment near Punahou. As Obama later told it, one morning Stan and Madelyn argued over her wanting him to drive her to the Bank of Hawaii instead of her continuing her years-long pattern of taking a bus. Madelyn said that on the previous morning an aggressive panhandler had continued to confront her even after she gave him a dollar. Barry offered to drive her downtown, but Stanley objected. He said Madelyn had experienced this before and had been able to shrug it off, but now her fear was greater simply because this panhandler was black. That angered Stan, who refused to take her.

In Obama’s later telling, Stan’s use of the word “black” was “like a fist in my stomach, and I wobbled to regain my composure.” Stan apologized for telling Barry, and said he would drive Madelyn downtown. Then they left. Stanley’s obvious comfort with people of color, as well as his liberal political leanings, may not have been fully shared by now fifty-seven-year-old Madelyn, and in Obama’s recounting years later he added that never had either grandparent “given me reason to doubt their love.” Yet he was struck by the realization that men “who might easily have been my brothers” could spur Madelyn’s “rawest fears,” at least when they aggressively approached her at close quarters.

Obama says he went that evening to see Frank Marshall Davis, who was now approaching his seventy-fifth birthday. Frank’s poetry from the years before his 1948 move to Hawaii was now being rediscovered and studied by a younger generation of African American literature scholars, several of whom had interviewed Frank about his long and fascinating life. Barry recounted his grandparents’ argument, and Frank asked if Barry knew that he and Barry’s grandparents had grown up hardly fifty miles apart in south central Kansas at a time when young black men were expected to step off the sidewalk if a white pedestrian approached. Barry hadn’t. Frank remembered Stan telling him that when Ann was young, he and Madelyn had hired a young black woman as a babysitter and that she had become “a regular part of the family.” Frank scoffed at that patronizing, but told Barry that Stanley was a good man even if he could never understand what it felt like to be black and how those feelings could affect black people.

“What I’m trying to tell you is, your grandma’s right to be scared. She’s at least as right as Stanley is. She understands that black people have a reason to hate. That’s just how it is. For your sake, I wish it was otherwise. But it’s not. So you might as well get used to it.” In Obama’s telling, Frank then fell asleep in his chair, and Barry left. Walking to the car, “the earth shook under my feet, ready to crack open at any moment. I stopped, trying to steady myself, and knew for the first time that I was utterly alone.”

That night was apparently the last time Obama saw Frank Marshall Davis. But no matter how overdramatized Obama’s later account may have been, his previous nine months at Oxy had exposed him for the very first time to mainland African Americans who had a racial consciousness that a Hawaiian who had hardly ever experienced even minor racial mistreatment could not grasp any more than his sixty-two-year-old white grandfather could understand what four decades of being a black man in mainland America had taught his friend Frank. And black Oxy students from South Central L.A. or St. Louis had more trouble feeling at ease in a 90 percent white institution than someone from Punahou could. Barry Obama’s Oxy classmates were not being racially obtuse when they saw their happy, relaxed, and reserved friend as a multiethnic Hawaiian rather than a black American.

Oxy’s fall term classes began at the end of September 1980. By then, Barry had accepted Hasan Chandoo’s invitation to share a two-bedroom ground-floor apartment in a small two-story, multiunit building at 253 East Glenarm Street in South Pasadena, a fifteen-minute drive from Oxy. Before the dorms opened, Hasan’s younger friend Asad Jumabhoy, an Indian-origin Muslim also from Singapore who was an entering freshman, crashed on their living room couch. Hasan had a yellow Fiat 128S, and Barry soon acquired a beat-up red Fiat coupe. Vinai Thummalapally and an Indian roommate lived upstairs, and Barry sometimes gave Vinai’s girlfriend Barbara a lift to or from Oxy.

Living off campus, Barry spent more time hanging out in the Cooler between and after classes. Cooler regular Caroline Boss cochaired Oxy’s Democratic Socialist Alliance, in which Hasan was active, and Hasan was also still coaching Margot Mifflin’s field hockey team. As Margot and Hasan got more involved, Margot and her roommate, Dina Silva, spent increasing time at Hasan and Barry’s apartment. “They had great social gatherings, parties, dinners,” Dina recalled, and Imad Husain and Paul Carpenter, still living in Haines Annex, plus Paul’s girlfriend Beth Kahn, were among the regulars. “They used to throw a great party there,” Paul agreed. “Food and dancing and a great mix of folks,” including Bill Snider and Sim Heninger from the old Haines Annex crowd plus Wahid Hamid, Eric Moore, and Laurent Delanney. Barry and Hasan went on outings with Wahid or Vinai and Barbara to places like Venice, where Margot took a photo of Barry, Wahid, Hasan, and Hasan’s cousin Ahmed all wearing roller skates.

Whether in the Cooler or at Glenarm, Hasan’s passionate interest in politics dominated many discussions. Hasan was “very outspoken about his political views, very aggressive, opinionated, extroverted,” Margot remembers, and identified himself as a Marxist—at least “to the extent that any of us knew what we were talking about,” as Susan Keselenko sheepishly puts it. Asad Jumabhoy concurs that “Hasan was very radical at the time” and “had very strong views and he could support his argument very well.” To Chris Welton, who returned to Oxy that fall after a year abroad and soon became a close friend after meeting Hasan in one of Roger Boesche’s classes, what everyone in Hasan’s circle shared was “an outlook” that contemplated the wider world beyond “the borders of the United States.” The crux of their orientation was “international, period,” or what Caroline Boss called a “more globalized perspective” than undergraduates who had experienced only the mainland U.S. could envision.

Irrespective of the venue, Hasan was “a force to be reckoned with,” Paul Carpenter recalls; Sim Heninger terms him “just a domineering personality.” Compared to Hasan, who “cursed like a sailor” while smoking incessantly, everyone saw Barry as quiet, measured, and reserved. Chris Welton remembers him as “a keen observer,” Caroline Boss would call him “mainly an observer.” Dina Silva thought of Barry as “quiet,” “thoughtful,” and “contemplative” during conversations. Obama “was listening and absorbing everything much more than being demonstrative,” Paul Anderson recalls. “He would watch people—that is what I remember,” artist friend and junior Shelley Marks recollects. “I specifically remember him being quiet and watching and observing.”

During the 1980–81 academic year, Barry and Hasan became the closest of friends. Hasan’s girlfriend Margot describes it as “an affectionate relationship,” one that “wasn’t hampered by masculinity issues. They were open with each other, affectionate with each other,” for Hasan was “an open, intimate, direct person.” Often the two of them would sit and study in their kitchen; Chandoo can picture Obama reading Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” at that kitchen table. Some nights Barry studied in a glass-enclosed area in the library’s basement that everyone called the Fishbowl. Other nights Margot Mifflin and Dina Silva would join Hasan and Barry to study on East Glenarm. Marijuana was a regular though perhaps not nightly relaxant for Hasan and Barry. “I got stoned with him many times,” Margot acknowledged when asked about that 1980-81 year. And, on a less regular basis, “we did occasionally snort cocaine” at Glenarm as well, although it was “not a routine part” of their lives at that time. Sim Heninger can remember nights of “uproar and hilarity” at Barry and Hasan’s apartment, but also at least one scene that was “a little scary for me.” Bill Snider, reflecting back on both Obama’s freshman and sophomore years, deftly remarks that “his memory may be a little hazy” both from those nights at Haines Annex and from the subsequent regular parties on Glenarm.

In mid-October 1980 Roger Boesche and faculty colleague Eric Newhall failed badly in an effort to persuade Oxy’s faculty to adopt a resolution demanding that the college divest itself of stock holdings in companies still doing business in South Africa. Oxy’s student newspaper immediately noted that two years earlier student activism had forced the issue to the top of Oxy’s agenda. Just days later, Caroline Boss announced that she and friends were reviving the Student Coalition Against Apartheid (SCAA). Oxy president Richard Gilman dismissed divestment as “an altogether too simplistic solution” while nonetheless acknowledging “the racist conditions in South Africa,” but a young sociology professor, Dario Longhi, who had studied in Zambia, took the lead in organizing a series of expert visiting speakers on South Africa for late in the fall term. Earl Chew took an active role while also complaining that Oxy lacked a “multicultural curriculum and social life” and needed far greater diversity.

Sometime late in the fall term, Eric Moore and Hasan Chandoo had conversations with Barry Obama about his name. Eric had spent part of the previous summer in Kenya as part of Crossroads Africa, a student educational program that dated from 1958 and in which Oxy was an active collegiate participant. “What kind of name is Barry Obama—for a brother?” Eric asked him one day. “Actually, my name’s Barack Obama,” came the answer. “I go by Barry so that I don’t have to explain my name all the time.” Moore was struck by Barack. “That’s a very strong name,” he told Obama, who then raised the issue with Hasan one day while they walked across campus. Chandoo agreed, and liked Barry’s middle name too. While most close friends like Paul Carpenter and Wahid Hamid had called him “Obama” instead of Barry and stuck with that usage, from that day forward Eric, joined only by Bill Snider, began addressing him as Barack while Hasan, being Hasan, would sometimes say “Barack Hussein,” as Asad Jumabhoy clearly remembers even thirty years later. Margot Mifflin too “can remember Hasan saying ‘He goes by Barack now,’ and I said, ‘Well, what is Barack?’ and he said ‘That’s his name.’ ” At the time, she recalls, “it was jarring.”

Over a quarter century later, Obama would say that he saw the change from Barry to Barack as “an assertion that I was coming of age, an assertion of being comfortable with the fact that I was different and that I didn’t need to try to fit in in a certain way.” With his Oxy friends “he would never correct you” if he was addressed as Barry, Asad explains, but when Obama returned to Honolulu for Christmas 1980, he told his mother and his sister that from now on he would no longer use his childhood nickname and instead would identify himself as Barack Obama. But to his family, just as with Hasan, Eric, and Bill, the name change signified no break in who they thought he was. As Snider explained, “I did not think of Barack as black. I did think of him as the Hawaiian surfer guy.”

Long breaks between academic terms gave Barack and his best friends plenty of opportunities to travel. One week Barack and Wahid Hamid headed down to Mexico, then northward to Oregon, in Obama’s red Fiat. Two days before the end of fall term exams, Hasan and Barack showed up in the Oxy library with a surprise birthday cake for Caroline Boss, who was hard at work on her senior thesis and whom they spoke with almost every day in the Cooler. Caroline invited the duo to stop by her family home in Portola Valley, near Stanford, over the holidays when Hasan and Barack would be on the road in Hasan’s yellow Fiat. Either before or after a New Year’s Eve party in San Francisco at which Hasan introduced Barack to another Pakistani friend, Sohale Siddiqi, Hasan and Barack arrived at midday at Boss’s home.

Her boyfriend John Drew, a 1979 magna cum laude Oxy political science graduate, was also there; he was in his second year of graduate school at Cornell University. Boss had spent the summer of 1980 in Ithaca taking summer classes, and Drew knew Caroline as “a fun, scintillating, hyper-extroverted,” and “intellectually vibrant” young woman who, despite her adoptive parents’ significant wealth, worked cleaning an Oxy professor’s home. That winter day in San Mateo County, the four young people headed out to lunch with Caroline’s parents; Drew recalled much of their conversation focusing on Latin America and particularly El Salvador. Back at the Bosses’ home, as Drew remembered it, he and Obama got into a “high-intensity” argument about the relevance of Marxist analysis to contemporary politics. Drew’s “most vivid memory” was how strongly Obama “argued a rather simple-minded version of Marxist theory” and that “he was passionate about his point of view.”

Drew recalled Obama citing the work of the late French Caribbean decolonization scholar Frantz Fanon. At Oxy Drew had been active in the democratic socialist student group, but a course that past fall with Cornell’s Peter Katzenstein had significantly altered Drew’s views. “I made a strong argument that his Marxist ideas were not in line with contemporary reality—particularly the practical experience of Western Europe,” Drew would recount years later. In Drew’s memory, “Caroline was a little shocked that her old boyfriend was suddenly this reactionary conservative,” but Obama shifted to downplay their degree of disagreement, conceding that there was validity to some of Drew’s points. Drew briefly saw Barack three more times during the remaining six months of his relationship with Boss before finishing his Ph.D., teaching at Williams College, and evolving into an ardent Tea Party conservative.

Oxy’s 1981 winter classes began on January 6. For the first two weeks of January, Hasan’s friend Sohale, who now lived in New York City, joined them in the Glenarm apartment as they hosted almost nightly parties. For Barack, though, this new term would be by far the most academically and politically engaging ten weeks of his collegiate career. One course he chose, Introduction to Literary Analysis, was taught by English professor Anne Howells, who had been at Oxy almost fifteen years. Utilizing the popular Norton Introduction to Literature, Howells had her fifteen students devote the first five weeks of the term to a “close reading of poetry—old-fashioned textual analysis” and then five weeks to reading short stories. There was “not very much reading, but a lot of writing”—five papers in the course of ten weeks. Barack “spoke well in class,” Howells would recall, and submitted well-written papers, but “he wasn’t a really committed student” and was late with assignments more than once.

Obama also enrolled in English 110, Creative Writing, which met Tuesday and Friday mornings 10:00 A.M. until 12:00 P.M., with David James, an Englishman who had graduated from Cambridge in 1967 and earned his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania in 1971. After teaching for nine years at the University of California at Riverside, James had arrived at Oxy just four months earlier. He required interested students to submit a writing sample prior to registration, an indication of the seriousness he brought to his teaching. At least five of the dozen or so students in the small class were earnest aspiring writers: Jeff Wettleson, Mark Dery, Hasan’s girlfriend Margot Mifflin, and Bill Snider and Chuck Jensvold, the older transfer student, both of whom Barack had known since his freshman year.

David James was “a marvelous character,” Dery recalled, “a classic British Marxist film theory jock” who was “a very penetrating analyst of poetry.” James handed out copies of contemporary poems he believed students would find stimulating, including ones by Sylvia Plath, W. S. Merwin, and Charles Bukowski, but viewed the course as “essentially a workshop to facilitate the students’ own compositions.” Jensvold’s presence was especially generative, for writing “seemed to define his whole being,” James remembered. In particular, Jensvold had an acute “eye for concrete detail” and knew that “amassing an inventory of details” was invaluable to a creative writer. Dery also appreciated Jensvold’s presence in what became “a very invigorating class.” Chuck was “an exemplar of the serious writer,” and as an older student he was “almost our mentor.” Dery and another classmate each referred to Jensvold as “hard-boiled,” and that classmate warmly remembered Chuck as “the Bogart of Occidental.”

Dery also recalled James as “a strict disciplinarian” who “didn’t suffer fools gladly” and had “zero tolerance for undergraduate lackadaisicalism.” A growing problem as the term progressed was students “straggling into class late.” One morning an angry James announced, “I am going to lock the door.” Soon a figure appeared outside the frosted glass door, unsuccessfully trying the handle. James did not react, nor to an ensuing tap or two on the classroom window. Finally Dery took the initiative to open the door, and in strolled Barack Obama. To Dery, Barack was “some species of GQ Marxist,” but an “almost painfully diffident” one whose “caginess,” even in the Cooler, made it hard to know “what he truly thought.”

A third course that winter was Political Science 133 III, the final trimester of Roger Boesche’s upper-level survey of political thought, this one covering from Nietzsche through Weber to Foucault. The fifteen or so students included Hasan as well as Barack’s former Haines Annex neighbor Ken Sulzer. Although memories three decades later would be hazy on the exact details, the results of two different assignments were notable in disparate ways. Sulzer and his friend John Boyer recalled seeing Obama heading into the library late one evening before an exam or paper was due. A day or so later, pleased with his own A-, Sulzer asked Barack what he had gotten, but Obama demurred. Sulzer grabbed Barack’s blue book and was astonished that Obama had gotten a higher A than he had.

Some weeks later, though, Boesche returned a paper on which he had given Obama a B. As both Barack and Boesche later recounted, within days, Obama encountered his young professor in the Cooler and asked, “Why did I get a B on this?” Boesche viewed Obama as “a student who gives incredibly good answers in class” but failed to consistently live up to his ability level on written assignments that required sustained preparation. In the Cooler, Boesche told Obama that he was smart, but “You didn’t apply yourself,” that he “wasn’t working hard enough.” Barack responded, in essence, “I’m working as hard as I can.” Boesche knew better than to believe that, but Obama would remain irritated about that B even a quarter century later, especially because Hasan Chandoo, not known for his academic diligence, received a higher grade for the term than did Barack: “I knew that even though I hadn’t studied that I knew this stuff much better than my classmates.” Obama believed Boesche was “grading me on a different curve, and I was pissed.”

Obama would allude to that experience a half-dozen times in later years, often not expressly mentioning Boesche but recounting how “I had some wonderful professors … who started giving me a hard time…. ‘Why don’t you try to apply yourself a little bit?’ And that made a big difference” in later years as Obama gradually came to appreciate that he was much smarter and far more analytically gifted than anyone who knew him at either Punahou or Occidental fully realized in those times and places.

Early 1981 was just as significant politically for Obama as it was academically. A listless rally on the first day of classes resulted in an Oxy newspaper headline reporting “Students Lack Interest on Draft Issue.” Six days later, an evening appearance by Dick Gregory, the comedian and political activist, that Hasan played a lead role in engineering, attracted a huge crowd of 550. Greeted by the “thunderous applause,” Gregory then spoke for more than two hours, offering up a pastiche of loony assertions about election tampering and CIA and FBI involvement in the killings of both Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King Jr., all somewhat leavened by countless humorous asides.

Two days later, a far more serious student forum explored all manner of prejudices at Oxy itself, with African American junior Earl Chew confessing, “Coming here was hard for me. A lot of things that I knew as a black student, that I knew as a black, period, weren’t accepted on this campus.” Three days later, in response to a flyer distributed on campus, Hasan and Barack drove to Beverly Hills to join 350 others in a silent candlelight vigil protesting the opening of a new South African consulate on Wilshire Boulevard. Relocation of the office there, from San Francisco, had attracted hundreds of protesters three months earlier when the consulate first opened. The vigil was cosponsored by the Gathering, a two-year-old South Central clergy coalition led by Dr. King’s closest L.A. friend, Rev. Thomas Kilgore, the L.A. chapter of King’s old Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the antinuclear Alliance for Survival.

Four days after that event, Thamsanqa “Tim” Ngubeni, a thirty-one-year-old South African member of the African National Congress living in exile in Los Angeles, addressed a lunchtime crowd of students on Oxy’s outdoor Quad. Born on the outskirts of Johannesburg in 1949, Ngubeni had joined the South African Students’ Organization in his early twenties and moved to Cape Town. A friend of prominent student leader Steve Biko, Ngubeni was arrested by South African authorities and imprisoned for several months before leaving South Africa and eventually making his way to L.A. in 1974, three years before Biko was killed while in South African police custody. A soccer scholarship enabled Ngubeni to attend UCLA, where he helped initiate the Afrikan Education Project and led demonstrations against the Bank of America’s involvement in South Africa.

In his January 21 speech at Oxy, Ngubeni told the students that South African apartheid “causes human beings to be considered as second-class citizens within their own country, the place where they were born and raised.” ANC’s goal was for black South Africans to be “recognized as human beings” in a country that had “more prisons than schools.” Ngubeni defended the ANC’s own use of violence against the South African regime, emphasizing that “we’ve been negotiating with them all these years while they were shooting us down in the streets.” He challenged Oxy’s students to reconsider which banks they patronized given how Bank of America and Security Pacific, like IBM and General Motors, continued to do business in South Africa.

Ngubeni often preached that “if you live for yourself, you live in vain. If you live for others, you live forever,” and his remarks that day certainly made an indelible impression on at least one of his young listeners. Barack Obama would tell two student interviewers a quarter century later that his meeting an ANC representative was the first time he thought about his “responsibilities to help shape the larger world.” Hasan’s intense politicization and their drive to Beverly Hills for the candlelight protest against South African apartheid were, like Roger Boesche’s professorial reprimand, the beginnings of an evolution that would flower more fully in the years ahead.

As winter term approached its midpoint, political events took place almost nightly. On Sunday evening, February 8, Hasan and Barack both attended a dinner held by Ujima as part of Black Awareness Month at Oxy. The next night Lawrence Goldyn delivered a scintillating talk, deftly titled “Why Homosexuals Are Revolting.” On Tuesday evening, Phyllis Schlafly, the conservative Equal Rights Amendment opponent, spoke at Oxy and was met with heckling from a trio of young men: Hasan Chandoo, Chris Welton, and Barack Obama. But the activist students’ primary focus was on the Student Coalition Against Apartheid’s upcoming divestment rally on February 18, scheduled to coincide with the next meeting of Oxy’s board of trustees. Oxy’s paper urged all students to attend since it “has the potential to be the most effective display of student initiative in recent years.”

Three students took the lead in organizing the rally: Caroline Boss, Hasan Chandoo, and Chris Welton. Caroline and Hasan decided the roster of speakers, with Hasan recruiting Tim Ngubeni to return as their keynote speaker, while Chris and Hasan handled the logistics for the noontime gathering just outside Oxy’s administration building, Coons Hall. No one can remember who first had the idea of opening the rally with a “bit of street theater,” in which two supposed South African policemen dragoon a young black speaker who wants to quiet the crowd, but Hasan and Caroline were two of Barack Obama’s closest friends. Obama later wrote that he prepared for what he expected would be two minutes of remarks prior to being dragged off.

Margot Mifflin and Chuck Jensvold videotaped the rally for a class project. A large banner calling for “Affirmative Action & Divestment NOW” hung in the background. Two folksingers played “The Harder They Come” and the crowd sang along before Barack, wearing a red T-shirt and white jeans, stepped up to the microphone. It was too low, forcing him to hunch over it. Barack asked “How are you doing this fine day?” before declaring that “We call this rally today to bring attention to Occidental’s investment in South Africa and Occidental’s lack of investment in multicultural education.” The crowd cheered and clapped. Barack, with his right hand in his front pants pocket, nodded and resumed speaking. “At the front and center of higher learning, we find it appalling that Occidental has not addressed these pressing problems.” The crowd cheered again, and Barack continued, “There is no—” before Chris Welton and another white student suddenly grabbed him from behind and wrestled him offstage, much sooner than Barack had expected.

“I really wanted to stay up there,” Barack later wrote, “to hear my voice bouncing off the crowd and returning back to me in applause. I had so much left to say.” In his own fictional retelling, he spoke much longer than actually was the case. “There’s a struggle going on,” he imagined having said. “I say, there’s a struggle going on. It’s happening an ocean away. But it’s a struggle that touches each and every one of us. Whether we know it or not. Whether we want it or not. A struggle that demands we choose sides.” In his recounting, Barack had gone on for another seven or more sentences, drawing cheers from the crowd and imagining that a “connection had been made.” But as Margot Mifflin later wrote after watching the videotape she had long retained, Barack’s version was “factually inaccurate” and “Obama’s speech was not long enough to be galvanic, or really even to be called a speech.” A detailed account of the rally in the next issue of Oxy’s student paper did not mention the opening skit at all. “Led by chants of ‘money out, freedom in,’ and ‘people united will never be defeated,’ ” the story said the ninety-minute rally attracted a crowd of more than three hundred, plus several local TV news crews.

As a few Oxy trustees and even President Gilman watched, Caroline Boss introduced Tim Ngubeni, who spoke briefly before giving way to senior Sarah-Etta Harris, a Cleveland native, Philips Exeter graduate, and Ujima leader with a glowing résumé that included a semester’s study in Madrid and a summer fellowship in Washington, D.C. A photograph taken by sophomore Tom Grauman during Ngubeni’s remarks captured a tall, regal Harris standing well apart from Caroline, Hasan, Obama, and other friends, including Wahid Hamid and Laurent Delanney.

Harris warned the crowd that by continuing to invest in companies that did business in South Africa, Oxy’s trustees “are telling us that they support oppression over there and also over here.” She then spoke directly about Oxy. “I can count the number of black faculty on two fingers, and black student enrollment has been going down steadily.” Harris drew cheers from the audience when she said she found it “hard to believe that the trustees cannot redirect their investments to correct some of the problems we have right here on campus.”

Many viewed freshman Becky Rivera as the day’s star speaker. “We’re upset,” she announced, and they were “demanding answers and demanding action.” Margot Mifflin remembers several African American women jumping to their feet during Rivera’s speech and exclaiming, “Say it!” Rivera closed by declaring that “students are responsible for revolutions. Students have power. It starts on the campuses.”

The rally’s final speaker was Ujima president Earl Chew. Caroline Boss remembers him as “so angry and on fire” but also “a kind person.” Chew was a complicated figure because he “had this prep school background, but at the same time he was very street.” After almost three years at Oxy, he was “very disillusioned” with a college that was “so painfully white.” Chew denounced Oxy’s idea of a liberal arts education as “a farce,” and excoriated the college for “taking our tuition and investing it in the oppression of our ancestral people.” Divestment “may not change the apartheid regime, but it’s letting our brothers and sisters in South Africa know that we … know better than to oppress other humans for economic gain.” As the rally broke up, Rivera sought out Obama to congratulate him on his role. “He really had been on the fringes politically up until that point,” Rivera recalled. She told him, “I wish you would get more involved,” but rather than thanking Rivera, Obama was simply “noncommittal.”

That evening Hasan and Barack hosted a party to celebrate everyone’s efforts. Caroline Boss remembers her exchanges with Obama that evening and, like Rebecca Rivera earlier, she was annoyed that he was openly moping rather than savoring his role. “I was really annoyed with him” when he started “yapping about how ‘I didn’t do a good job, and I could have said it better.’ ” As Boss recalled, “we all sort of went ‘Shut up! It was great. It was fine. You did what you were supposed to do. Move on.’ ” She was irritated that Barack viewed their group effort only in terms of himself. “The rally wasn’t about you developing your technique,” she spat out. “It was about South Africa, not you.”

Obama would recall a similar conversation with Sarah-Etta Harris, who had quietly befriended him a year earlier. Boss’s annoyance was grounded in the many discussions she had had with him in the Cooler, including ones about Obama adopting Barack in place of Barry. “A lot of the year’s conversations when they weren’t about politics was about identity, me talking about being adopted and him talking about sort of this weird experience of who’s his father and where’s his mother.” Caroline’s adoptive parents came from Switzerland, and were now wealthy, but Caroline’s maternal grandparents had been peasants who worked as a janitor and maid in an Interlaken bank. “I was very forthright about my own feelings about my adoptive state,” Boss remembers, and Barack was “absolutely” clear that he was wrestling with his own feelings about having been abandoned by both his birth parents. “That was something where he and I had a kind of a common understanding,” she explains, “of what it means to try to figure all that out.” Regarding his mother, Barack “was just very conflicted that she was absent so much,” yet given her resolute independence “he admired her enormously and of course found her irritating.”

Obama and Boss also discussed “class and race,” with Boss citing her grandmother’s story to argue the primacy of the former over the latter. Her grandmother had “a royal name,” Regina, despite her humble life circumstances, and Boss made Regina “a prominent part of some very intense conversations concerning the relationship between class and race.” She said Barack talked “about a lot of things that he’s seeing and feeling” with regard to race in the U.S. Boss said she would reply, “Yeah, but my grandmother in Switzerland—you have to see this internationally—my grandmother’s scrubbing those floors, and my mother and her brothers aren’t allowed to go into most of the town. The police will come and get them because they’re in the tourists’ place because they’re just these little local brats as far as the town council was concerned, so class is huge.”

Fifteen years later, Obama combined these reprimands into an account of how a woman named “Regina” upbraided him after he responds to her kudos about his skit with cynical sarcasm, saying that it was “a nice, cheap thrill” and nothing more. Regina replies that he had sounded sincere, and when Obama calls her naive, Regina counters that “If anybody’s naive, it’s you” and tells him his real problem: “You always think everything’s about you…. The rally is about you. The speech is about you. The hurt is always your hurt. Well, let me tell you something … It’s not just about you. It’s never just about you. It’s about people who need your help.”

In Obama’s telling, that night at the party another friend approaches and recalls the awful messes they had left in the Haines Annex hallway a year earlier for the poor Mexican cleaning ladies, to which Barack manages a weak smile. “Regina” angrily asks Obama why he thinks that’s funny. “That could have been my grandmother,” she said. “She had to clean up behind people for most of her life. I bet the people she worked for thought it was funny too.” In truth, it was not Harris but another African American woman, young American studies professor Arthé Anthony, who had objected when someone mentioned the dorm messes during a conversation in Barack and Hasan’s kitchen.

In future years, Obama would embrace the mantra of “It’s not about you” as a core life lesson and as a powerful antidote to what he described as “the constant, crippling fear that I didn’t belong somehow.” He would invoke the story of a cleaning lady “having to clean up after our mess” on subsequent occasions both obscure and prominent, and would cite a friend’s rebuke about her grandmother having cleaned up other people’s messes. With one interviewer, Obama would fuzz the details, saying, “I remember having a conversation with somebody and them saying to me that, you know, ‘It’s not about you, it’s about what you can do for other people.’ And something clicked in my head, and I got real serious after that.”

Obama would recite the moral of the story—“It’s not about you. Not everything’s about you”—without naming Harris, Boss, or Anthony. In one rendition, Obama said the rebuke had come from a female professor, but in his written account of that night, he gave Regina the biography of the tall, regal Sarah-Etta Harris. His physical description of Harris was distorted—only her “tinted, oversized glasses” match up to the Harris of 1981—and he says she was brought up in Chicago, not Cleveland, but the other history he attributes to “Regina” is drawn from Harris’s own undergraduate achievements. Most of Obama’s Oxy friends have difficulty remembering Harris, but “Regina” leaves Oxy “on her way to Andalusia to study Spanish Gypsies.” A 1981 Occidental promotional prospectus highlighted Harris’s receipt of a Watson Fellowship and said she “will travel to Hungary, France, Italy and Spain to study the socio-economic problems of sedentary gypsies of those countries.” Obama’s account accurately details the lifelong impact that Harris’s, Boss’s, and Anthony’s rebukes of his self-centeredness had on him, but the “Regina” story merges no fewer than three conversations into one.

The same issue of the Oxy newspaper that covered the rally on its front page also featured “Rising Above Oxy Through Columbia.” Junior Karla Olson wrote that a year earlier she had been “stuck in a rut” at Oxy. Deciding that she needed to try another institution, “I tried to pick a college the polar opposite of Oxy” and “within a month I had applied and been accepted as a visiting student to Columbia University in New York City.” Upon arriving there, she had been presented with “Columbia’s catalogue of 2,000 or more available classes,” a stark contrast to tiny Occidental. Olson knew Columbia was “an Ivy League school,” but “I soon realized that I wouldn’t have to work nearly as hard as I do at Oxy.” Olson lived in Greenwich Village, where she had easy access to “museums, art galleries, Broadway, Fifth Avenue, Central Park, clubs, bars, restaurants, and a myriad of other diversions.” It seemed as if “95 percent of Columbia students live off-campus, and most go straight home from class … making it really hard to meet people,” but “my overall experience at Columbia was fantastic…. I learned a lot from my classes and benefited even more from the opportunities New York offered in my spare time.”

At Occidental, many if not most students thought about transferring to larger institutions. Eric Moore, who tried unsuccessfully to transfer to Stanford, believed “most people were trying to transfer from Oxy,” and Phil Boerner, Obama’s across-the-hall friend from Haines Annex, “wanted to attend a larger university” and one that was less “like Peyton Place” than Oxy, where “everybody knew who was dating who.”

Nineteen-year-old Barack Obama had never even passed through New York City, and he knew no one there aside from Hasan’s friend Sohale Siddiqi, but one day he asked Anne Howells, his literature professor, if she would write a letter of recommendation for him to Columbia University. “He wanted a bigger school and the experience of Manhattan,” Howells recalled years later. “I thought it was a good move for him.” Oxy assistant dean Romelle Rowe remembers Barack discussing a transfer to Columbia and saying he wanted “a bigger environment.” Years later Obama would say he transferred “more for what the city had to offer than for” Columbia, that “the idea of being in New York was very appealing.” Crucial too was how his closest friends were soon leaving Occidental. Hasan and Caroline were graduating in June and both were headed for London, Hasan to join his family’s shipping business and Caroline to study at the London School of Economics. Wahid Hamid, in a dual degree program, was about to shift to Cal Tech.