По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

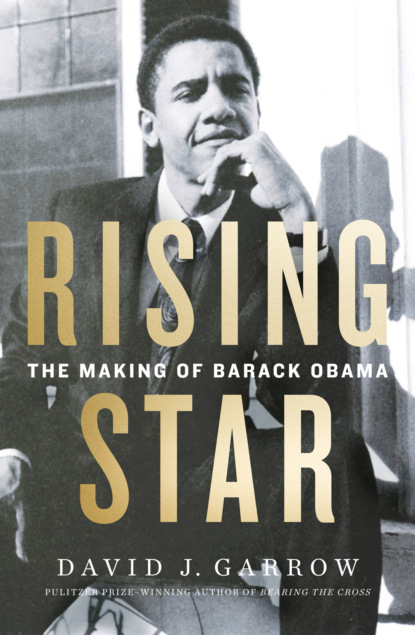

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

With Genevieve, Barack spoke of BI “only to be disparaging” and only “very rarely” did he speak about his actual five-days-a-week work tasks. “His entire attitude was bearing a necessary burden” and one he was deeply uncomfortable with. “Even just putting on the clothes to go to work in that environment was a political divide—it divided him from how he really saw himself,” she later explained. “He definitely wore it like a penance.” On weekday evenings, Barack’s posture was “They’re the enemy, and I’ve just spent all day at work” but also that “I’m above being emotionally affected by my job.”

His coworkers at BI quickly picked up on Barack’s emotional distance. Cathy Lazere, his immediate supervisor, noted his “aloofness.” “He came across as someone not interested in other people,” she said. Beth Noymer, his closest colleague, said he was “quiet and kind of kept to himself.” To vice president Lou Celi, Barack came across as “shy and withdrawn” and “always seemed aloof.” Lou’s deputy Barry Rutizer thought Obama “was kind of self-involved” and “somewhat withdrawn.” Lou’s assistant Lisa Shachtman remembered Barack as someone who was “sitting back and observing” others rather than interacting with them. BIMR editor Dan Armstrong recalled that Obama “really just kind of kept to himself” and “never joined us” when everyone went out after work. Dan thought “diffident” was the perfect adjective, and in Peggy Mendelow’s memories Obama “had an obvious ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign on him.” Years later one colleague would describe Barack as “the whitest black guy I’ve ever met.”

Barack’s life with Genevieve on 114th Street, where she came on Thursdays after a class at Bank Street as well as on weekends, was a separate world from his workday week. In mid-February, Genevieve recorded that Barack the night before had “talked of drawing a circle around the tender in him—protecting the ability to feel innocence and spring born—I think he also fights against showing it to others, to me.” The next day, Presidents’ Day, she recorded her worries about her “unwillingness to believe that he really does like the time spent with me, that he likes me.” Alluding to BI, it “makes me cross that he’s sitting there in that office while all the others take the day off—too soon to scorn the blatant taking advantage of the least powerful on the totem pole—but I hope he will soon find a way to make it clear he sees limits to what can be thrust on him—the loose ends, the overtime.” Her thoughts returned to their weekend together. “It means so much more than lust, after all, all this fucking we do.” Four days later, after Thursday night together, she wrote of “making love with Barack, so warm and flowing and soft but deep—relaxed and loving—opening up more.”

But Genevieve had her own self-doubts. “It’s all too interior, always in his bedroom without clothes on [or] reading papers in the living room. I’m willing to sit and wait too much.” Barack did go out to Long Island one weekend to see Wahid, who had now married his longtime girlfriend Ferial “Filly” Adamjee, yet with Genevieve their time together was interior indeed. She worried “that what men reach for and stay with is the availability to them of a warm time in bed, while they put up with or dismiss the ‘noise’ women ‘indulge’ themselves in.” While “the sexual warmth is definitely there … the rest of it has sharp edges, and I’m finding it all unsettling and finding myself wanting to withdraw from it all. I have to admit that I am feeling anger at him for some reason, multi-stranded reasons. His warmth can be deceptive, tho he speaks sweet words and can be open and trusting, there is also that coolness … Both of us wary … and that is tiring.”

The next weekend found a return to warmth, with Genevieve pleased by Barack’s compliments, “his saying ‘You’re sweet to me,’ that I’m kind, as if he’s not accustomed to that, has not had much of that.” One evening at dinner, Genevieve recorded, she had an image “of being with Barack, 20 years hence, as he falters through politics and the external/internal struggle lived out.” One week later, with Genevieve experiencing a bout of tearful self-pity, “Barack said he used to cry a lot when he was 15—feeling sorry for himself.” Fifteen would have been his tenth-grade year at Punahou, when Barack was closest to Keith Kakugawa, but Genevieve was happy that he “won’t let important things go unspoken. ‘Speak to me.’ ”

Yet more often Genevieve felt a self-distancing on Barack’s part, “a sense of you biding your time and drawing others’ cards out of their hands for careful inspection—without giving too much of your own away—played with a good poker face. And as you say, it’s not a question of intent on your part—or deliberate withholding—you feel accessible, and you are, in disarming ways. But I feel that you carefully filter everything in your mind and heart … there’s something also there of smoothed veneer, of guardedness … I’m still left with this feeling of … a bit of a wall—the veil.”

In early March, Genevieve moved from her parents’ Park Avenue apartment to a top-floor, two-bedroom apartment in a Park Slope brownstone at 640 2nd Street that was owned by relatives of a Brooklyn Friends School secretary. One mid-March morning, she telephoned West 114th Street and for a moment mistook the voice of the third roommate, Michael Isbell, for Barack. Michael’s firm “I’m good” in response to Genevieve’s “How are you?” made her realize “that Barack often doesn’t feel firmly good.”

Barack and Genevieve saw even less of Michael than they did of Dawn Reilly, whom they mostly interacted with on Sunday mornings. Michael worked in advertising, had a full-time girlfriend, and remembered Barack as a quiet, studious smoker. Michael did not get along with Dawn as well as Barack did, and Genevieve believed Dawn “had this kind of motherly attitude towards” Barack, even though she was just five years older. Genevieve remembers Dawn as “a vivacious character … very fond of Barack” and “she thought we were a very cute couple. She saw enough of us that she was very aware when things were good” and also when “things got a little bit strained.” Genevieve recalled that in mid-March, Dawn told her, “ ‘I feel more tension between you two’ ” and said she believed Genevieve was good for Barack, whom she thought was confused about what he wanted. To herself that day Genevieve wrote, “I’m a little worried about Barack. He seems young and defenseless these days.”

Barack intrigued Genevieve greatly, but there is “so much going on beneath the surface, out of reach. Guarded, controlled,” she wrote to herself. Genevieve took the initiative to buy them tickets to a one-woman performance of three short plays by Samuel Beckett at his namesake theater on West 42nd Street. In the last of them, Rockaby, actress Billie Whitelaw onstage uttered just one word, “more.” In between her four increasingly fearful incantations of that one syllable, the audience heard “the tortured final thrashings of a consciousness, as recorded by the actress on tape.” At its close, the audience experienced “relief” as “death becomes … a happy ending,” New York Times critic Frank Rich wrote, saying it was “riveting theater … that no theatergoer will soon forget.” In her journal, Genevieve wrote that “Billie Whitelaw was superb.”

At the end of March, Hasan Chandoo arrived in New York to prepare for his move from London to Brooklyn in early summer. The 1984 Democratic presidential race was in full swing, and on Wednesday evening, March 28, top contenders Walter Mondale and Gary Hart were joined by third-place contestant Jesse Jackson for an intense televised debate from Columbia’s Low Library, moderated by CBS’s Dan Rather. By that time Obama was actively interested in Jackson’s campaign, and the next Saturday, March 31, he persuaded Hasan, Beenu Mahmood, now in his first year at Columbia Law School, and even Sohale, to join him in attending a Jackson campaign rally on 125th Street in central Harlem. Three days later, Jackson finished a strong third in the New York primary with over 25 percent of the vote, including presumably Barack’s. Both Hasan and Beenu also remember that spring and summer that Barack often carried with him a well-worn copy of Ralph Ellison’s famous 1952 novel Invisible Man, which he was reading and rereading. Beenu believed that “Invisible Man became a prism for his self-reflection,” and in retrospect Beenu thought that over time “Ellison assisted Barack in reaching a fork in his life.”

But that fork was more than a year away. Later that night, Barack and Genevieve joined Hasan and Sohale at the latter’s East 94th Street apartment, where Barack had lived a year earlier. “Long time friends, easy with each other but also challenging,” Genevieve wrote in her journal the next day. Everyone “did several lines of cocaine, which added an edge to it all.” For Barack, the almost three years that had passed since he lived with Hasan in South Pasadena in 1980–81 had been almost entirely drug-free, certainly when compared to that year at Oxy and indeed the three previous as well. His twelve months living with Sohale in 1982–83 had seen plenty of “partying” by Siddiqi, but only with Hasan’s incipient move to New York would Barack feel compelled, on account of their friendship, to reengage in something that without Hasan he felt no need to seek out. He was seriously involved with a woman who smoked pot daily, but except when they were at parties with Hasan, Sohale, and Imad, Barack and Genevieve did not partake of such pursuits.

Before the end of that weekend, Barack told Genevieve that “I really care very much about you” and that “No matter how things turn out between us, I always will.” She wrote in her journal that he talked to her as well about his “tendency to be always the observer, how to effect change, wanting to get past his antipathy to working at BI.” A week later “Barack talked of his adolescent image of the perfect, ideal woman—searching for her at the expense of hooking up with available girls.” Presently she imagined him “opting for dirtying his hands in the contradictions and overwhelming complexities this city offers” and resolved that “I must enjoy Barack while I can.” Recounting a scene Barack had described to her, “The image of Barack shaking his grandpa by the shoulders and asking ‘Why are you so damn unhappy?’ really struck me.”

In early April, Barack received a call from Alex McNear, who was still living in Eagle Rock, and soon after, he sent her a long letter, one that portrayed his role at BI somewhat differently from how his coworkers and Genevieve did. “I’ve emerged as one of the ‘promising young men’ of Business International, with everyone slapping my back and praising my work. There is the possibility that they offer the job of Managing Editor for one of the publications, which would involve a hefty raise, but an extended stay,” Barack asserted. “The style and substance of what I write” was such that “I can churn out the crap without much effort” yet “the finished product confronts me as an alien being, not threatening, but a part of another system, another sensibility.”

Barack’s description of some of his interactions with colleagues beggared belief. “Without effort, I find I can perform with flawless grace, patching up their insecurities, smoothing over ruffles among the co-workers.” Yet he described his own attitude with considerable accuracy. “All of them, including my superiors, sense some sort of tethered fury, or something set aside, below the calm surface … so that I remain somewhat alien to them.” Indeed “the implacable manner is not an act, nor is the anger underneath,” but Barack acknowledged that his colleagues “are good people, warm and intelligent.” He told Alex, “I’ve cultivated strong bonds with the black women and their children in the company, who work as librarians, receptionists,” and reported that the only other black men “one sees are teenage messengers.”

Barack admitted “the resistance I wage does wear me down—because of the position, the best I can hope for is a draw, since I have no vehicle or forum to try to change things. For this reason, I can’t stay very much longer than a year. Thankfully, I don’t yet feel like the job has dulled my senses or done irreparable damage to my values, although it has stalled their growth.” But, “like other malcontents, I have my other life as opposed to my working life … weeknights I spend a few hours writing, a few hours eating, and take occasional walks along the river. I recently finished the first fiction piece I’ve attempted in over a year, and I got some good feelings doing it, even though it’s not top quality. I still have a certain ambivalence towards writing/art as a vocation.” As for “my political reading/spectating—my ideas aren’t as crystalized as they were while in school, but they have an immediacy and weight that may be more useful if and when I’m less observer and more participant. On weekends I see Sohale, Wahid et al. fairly frequently and let myself slip back into old comfortable activities like bullshitting and watching basketball,” though to Alex, Barack made no mention of his reintroduction to cocaine. He confessed that “I’ve also become quite close to an Australian woman who teaches in a Brooklyn grade school. She doesn’t put up with a lot of my guff, and has a good sense of humor without any cynicism, which is a good tonic for my occasional attitude problems.” Obama ended the letter by saying “look forward to seeing you in the summer if you choose to come back East. Love, Barack.”

The divergence between how Obama described his interactions with his BI colleagues and how they viewed him was great indeed. Eugene Chang, one of the two editors of the finance unit’s lead newsletter, Business International Money Report, made an effort to get to know Obama, inviting him to lunch at a Korean restaurant and mentioning how he jogged. Barack’s responses were chilly and abrupt: “I don’t jog, I run.” Susan Arterian, a decade older than Obama, thought “there was a certain hauteur about him and a somewhat cultivated aura of mystery.” To her, “BI was a friendly place” with lots of “wonderfully quirky characters,” and Eugene’s BIMR coeditor, Dan Armstrong, saw Barack as “reserved and distant towards all of his coworkers,” notwithstanding how BI was “not a corporate place in any way.”

Bill Millar, a 1983 graduate of CUNY’s Baruch College, found Obama “arrogant and condescending,” someone who “treated me like something less than an equal” even though Millar was a higher-ranking assistant editor. Millar once argued with Barack about corporations that did business in South Africa, and another colleague, Tom Ehrbar, recalled Barack quarreling about the CIA with another coworker who did not remember the exchange. As Peggy Mendelow described Barack, he “kept very much to himself” and “didn’t seem to want to be there.”

Barack was far more interested in old friends than in making new ones. Genevieve described “Barack’s face opening up in a broad grin after talking with Bobby [Titcomb] on the phone in Honolulu.” She also described their sexual interactions positively: “really communicating instead of merely getting off.” At the end of April, Genevieve wrote, “I’m falling in love with Barack…. Spent Sunday with Barack in the park.” They saw a boy in a sandbox “with his Superman cape on, and I launched into some kind of spiel about kids and imagination and fantasy, and he launched into this thing about superheroes and was revealing about some relationship he had to superheroes, and I thought, ‘Oh my God, that’s fascinating, I’ve never heard him come out with that before,’ and I pounced on it and wanted to really like push an exploration of it” but Barack gently rebuffed her.

At the end of April, old Oxy friend Sim Heninger came through New York and stayed with Phil Boerner, who was just about to finish his degree at Columbia. One evening, Sim, Phil, and Phil’s girlfriend Karen had dinner with Barack and Genevieve. Sim in particular was struck by the seriousness of their romantic attachment. Early in May, however, Genevieve detected a “deliberate distancing” on Barack’s part and wrote, “I think I am probably being rejected more for what I represent in Barack’s mind than for who I am.” She imagined that Barack would be more comfortable with a black woman, and she wrote in her journal, “I think I’ve known all along that he plots this into his life as something temporary—not open-ended as he had said.” She wondered if they were just “using each other,” yet understanding what was going on was difficult, because “he is so wary, wary. Has visions of his life, but in a hiatus as to their implementation—wants to fly, and hasn’t yet started to take off.”

Within a week their relationship had righted itself, although Genevieve was feeling “depressed about teaching” as the school year was ending. “It so delights me that from time to time, Barack will talk about the more private, inner aspects of what he sees and feels of our relationship.” In late May, Barack told her one night “of having pushed his mother away over the past 2 years in an effort to extract himself from the role of supporting man in her life—she feels rejected and has withdrawn somewhat.” By then he knew his mother and sister were moving back to Honolulu in mid-August. Ann had learned in February that her Ford Foundation post would expire in six months. She had resolved to make the best of that by returning to her long unfinished Ph.D. at the University of Hawaii, a move that would allow soon-to-be fourteen-year-old Maya to begin ninth grade at Punahou. Ann wrote the chairman of UH’s Anthropology Department to say that “the major reason” for her long absence from the program had been “the need to work to put my son through college,” and with his graduation, “I’m now free to complete my own studies.”

Once classes ended at Brooklyn Friends School, Genevieve left New York to spend a week at her stepfather’s family’s estate in Norfolk, Connecticut. She dreaded the next school year, when she would be teaching first grade at PS 133 in Park Slope. “I’m feeling really bad about myself in general,” she wrote in her journal, and by phone Barack sought to reassure her. By early June, Hasan Chandoo had an apartment at the Eagle Warehouse building on Old Fulton Street underneath the Brooklyn Bridge, and both there and at Sohale’s apartment on East 94th Street, Barack and Genevieve joined some assortment of the Pakistani friends almost every weekend. If Wahid came into the city, or if Beenu and his girlfriend Chinan were present, drinks and dinner would be the centerpiece of an evening. But with Hasan, Sohale, and Imad, pot and cocaine were usually involved, though Barack’s ambivalence about those activities was crystal clear to Genevieve and obvious to Hasan too.

Sometimes Barack would beg off, but most times he asked Genevieve to come along—“We’ll go together,” he would say—knowing that one or both of them would try to leave before the evening got too late or the activities got too “out of control and manic,” as Genevieve described it. For all her pot smoking, Genevieve did not care for cocaine, yet Barack “didn’t like it when I said ‘Well I’m going to leave now’ or ‘I don’t feel like coming’ ” because “that made it harder for him to ignore the fact that he didn’t really want to go either, that he would have rather stayed home and read.”

But Barack’s bond with Hasan was stronger than his self-discipline, and Genevieve thought “it seemed important to Barack that I bolster him in his desire to maintain allegiance to the guys.” To her, Barack’s indulgence “was definitely out of loyalty and an inability to kind of give the flick to people who had been so incredibly loyal and embracing” of “this lost boy, who had no group, who had no community, and they knew him from before,” from Oxy, “and embraced him warmly.” Hasan was “absolutely” the driving force, not Sohale or Imad, and while that trio was “doing lots of cocaine,” Barack “did not do as much as they did.” Indeed, Barack did “a lot less of everything, like for every five lines that somebody did, he would have done half, and for every scotch that Hasan poured, he would have had one out of every ten compared to what Hasan was drinking.”

In a more understated voice, Hasan agreed with Genevieve. “We dabbled in drugs,” but with Barack “there wasn’t anything excessive by him, by my standards.” As of that 1984 summer, Obama was “much more serious” than the college sophomore Hasan had lived with three years earlier, and at times Barack “would tell me to go easy on my drinking or my smoking pot, and I’m saying ‘What a change!’ ” Genevieve recognized a tension between Barack’s loyalty to his Pakistani friends and his emerging realization that “somehow splitting himself off from people is necessary to his feeling of following some chosen route which basically remains undefined.” She continued to worry about “veils and lids and control,” but Genevieve enjoyed being “cosseted in Barack’s apartment” on weekend nights before returning to her Brooklyn apartment and a new roommate whose presence she found irritating. Genevieve found her intimate time with Barack special and uplifting, but she was sometimes troubled by his behavior toward the Pakistanis, writing one night that “the abruptness and apparent lack of warmth with which Barack left them was jarring.”

A few days later Hasan and Barack had dinner at Genevieve’s apartment, and she remained fascinated with Barack’s deeper, preoccupying thoughts. He talked about Ernest Hemingway “and the integrity of grasping for those times, those visions that are ones of true magnificence and profundity,” but “when Barack speaks of missing the signs of some central, centered connection with the powerful maelstroms of deep feeling, grand scopes, I have responded with comments such as ‘Maybe you need not to look for them at such dizzying heights, but on other levels.’ ”

In mid-July, Genevieve took offense at “all the artifice in his manner,” but a large Saturday-night dinner at Hasan’s that included his cousin Ahmed, Beenu and his sister Tahir, and Wahid and his wife Filly left Genevieve impressed with Filly’s intelligence and independence. Yet Genevieve’s persistent self-doubts continued to trouble her feelings about Barack. “How long will it take him to see that I am silly and insecure and inarticulate in a way he will find repulsive rather than acceptable?” she wrote in her journal.

A trio of cheap photo booth pictures the couple took of themselves that summer shows Genevieve looking exceptionally energized, striking, and happy, and a somewhat full-faced Barack looking pleased and happy as well. On the first Sunday in August, Genevieve challenged him to a footrace in Prospect Park near her apartment. Barack greeted the challenge with gently mocking bemusement, but then, to his utter amazement and chagrin, Genevieve won, demonstrating that he had seriously underestimated her. “Barack couldn’t really believe it and continued to feel a bit unsettled by it all weekend” as they showered and then went to see a new film, James Ivory’s The Bostonians, starring Vanessa Redgrave and Christopher Reeve. “Being beaten by a woman,” especially when Barack prided himself on his almost daily running, “really unsettled him,” Genevieve recalled.

Genevieve believed that Barack’s running was motivated by unpleasant memories of having been a chubby boy in his pre-basketball years. “There was still quite a bit of ‘I was a fat boy’ feeling lurking underneath his resolve to be so disciplined with the running. He was very trim, except for a bit of pudgy tummy,” which “he couldn’t get rid of” and “was quite self-conscious about,” she remembered. “That’s why he ran,” to “get rid of that last little bit of being a pudgy boy.”

That did not hinder what she described as “passionate sex,” and after a week apart when Genevieve went to London, she returned to find Barack troubled after having been told by his African sister Auma, who hoped to visit New York in November, about a rumor that their father may have been murdered rather than killed by his own drunken driving. Barack and Auma had become irregular correspondents following Obama Sr.’s November 1982 death, and either just before or just after this latest word from Auma, Barack had a memorable dream about his father that he shared with Genevieve, who had also “grown up without my dad.” But now he also told her that a month earlier he had cried when he saw television news coverage of a mass murder that claimed the lives of twenty-one people at a fast-food restaurant near San Diego. “Interesting that he was connecting the two,” Genevieve wrote in her journal, “when in fact the tears he cries are, I’m sure, buried tears over his dad, and the loss over all the years without him. He was very subdued” for the balance of that weekend.

To Genevieve, who was “constantly looking for an explanation for this wary guardedness” she so often felt from Barack, the answer lay in how “he was not in touch with how deeply wounded he was by his mother’s and his father’s relationships with him.” In her mind, Barack’s “woundedness” and “abandoned child persona” meant “the amount of suppression of negative emotion is just heroic” and explained why “there was a ‘no go’ zone very, very quickly” whenever talk about deep personal feelings threatened to undermine all of that successful suppression.

In late August, Alex McNear called Barack to say she would be arriving in New York on August 23. The two of them had dinner that night, although years later Alex would have no memory at all of that evening. Genevieve was not looking forward to the start of her school year at PS 133, but in her journal she again wrote, “I love him very much.” Obama met up with Mike Ramos for a beer one night when Mike came to New York for the first of two training events for his job at a large accounting firm. Barack talked about quitting his job at BI so he could do something more rewarding, and Mike, impressed with his friend’s courage, ended up crashing at 114th Street rather than making it back to his hotel. Either during that visit or when Mike returned to New York just before Halloween, they had dinner one night with Genevieve, whose unusual name Mike would remember years later.

Early in the fall, Phil Boerner, Barack, and another old Oxy friend, Paul Herrmannsfeldt, who was working at a publishing house, started a book discussion group at Paul’s seventh-floor apartment in Soho. Their first selection was Samuel Beckett’s 1938 novel Murphy, and Phil’s girlfriend Karen plus several friends of friends attended two or three subsequent meetings, but the group petered out within two months. Barack also attended a reading by several writers at the West End bar on Broadway just south of 114th Street that his apartment mate Michael organized just prior to moving out, but his attempt to interest Michael in his own work failed. As Phil later said, they all found Barack “an interesting yet unremarkable person,” a young man whom some saw as “a bit smug” but whom no one imagined would ever be seen as an exceptional individual.

At BI Barack’s colleagues felt similarly. In early fall, Lou Celi and Cathy Lazere launched a new series of “Financial Action Reports” that required updating BI’s data on companies’ cash management strategies in particular foreign countries, with new information gleaned from interviews with corporate treasurers. The first two countries were Mexico and Brazil, and Obama and the slightly more senior Michael Williams were given a task that Williams remembered as “my least favorite project” at BI. About twenty treasurers had to be contacted either by phone or in person in New York, and the thirty-minute interviews had to be transcribed. Williams and Obama each took half, and though Williams recalled transcribing his own tapes, Lou’s assistant Lisa got newly arrived editorial assistant Jeanne Reynolds to transcribe at least one of Obama’s more difficult ones. Williams remembered Barack as someone who “kept to himself,” spoke only when necessary, and never seemed “fully engaged.” That was atypical indeed at “a very friendly place” with “a pretty hip crowd” that offered great opportunities for advancement “if you wanted them.”

Jeanne Reynolds recalled Barack as “quiet, reserved, polite,” and Barack’s copy editor on the Mexico and Brazil reports, newly arrived Maria Stathis, would likewise remember him as “very quiet.” Another new arrival, Gary Seidman, remembered Barack teaching him to use the Telex machine that was cheaper than the telephone for international communication. Barack seemed “aloof,” a stark contrast to his “vibrant” coworker Beth Noymer. When Obama gave Cathy Lazere formal notice one day in November that he was quitting effective early December, Cathy mused that “it must have been a little lonely for him to work at a place for a year and not be fully engaged in the world around him.”

A few days earlier, his sister Auma called from Nairobi to say she was canceling her New York trip because their younger brother David Opiyo had just been killed in a motorcycle crash at age sixteen. That news may have strengthened Barack’s resolve to leave a job he found so foreign to his political views, and although he told Cathy “he wanted to be a community organizer because he didn’t find business that meaningful,” he also was leaving BI without a new job in hand. Cathy, Gary Seidman, and the young man Cathy interviewed and then hired as Barack’s replacement, Brent Feigenbaum, all had the impression that Barack was considering law school in addition to community organizing. In Barack’s exit interview, Lou Celi told him, as he told everyone leaving BI, that he was making a big career mistake, and when Barack told editor Dan Armstrong he did not yet have a new job, Dan asked, “Are you crazy?” He also told Barack he at least should “get another job before you quit.” In Armstrong’s memory, Barack simply shrugged. Feigenbaum spent one day working alongside Barack and recalled him as “remote … not a terribly warm person.” Beth Noymer’s monthly calendar for December 1984 would show “Barack lunch” on Friday the fourteenth, but neither she nor Cathy nor anyone else had any memories of a farewell meal.

Asked two decades later what he recalled from his time at BI, Barack answered “the coldness of capitalism.” He told an earlier questioner, “I did that for one year to the day,” a clear indicator of his desire to leave that world for something he found more fulfilling. But giving up his BI paycheck meant leaving the apartment on West 114th Street, and on the weekend of December 1 and 2, Barack temporarily moved in with Genevieve on the top floor of 640 2nd Street in Park Slope.

Earlier in the fall, they had taken the bus to her family’s estate in Norfolk, Connecticut, where they slept in an open-air cottage and joined Genevieve’s mother and stepfather for one meal. Barack later recounted paddling a canoe on a nearby pond, and a photo shows a happy and relaxed young couple outdoors in the morning sun. Their first week together in Genevieve’s cramped quarters produced minor irritations, but a nice weekend then included seeing the Eddie Murphy film Beverly Hills Cop in downtown Brooklyn. Genevieve was the only white person in the audience, but she says she and Barack never experienced any hostility or rudeness toward them as an interracial couple.

In the days just before Barack left to spend the holidays in Honolulu, their feelings of being in each other’s way multiplied, with Barack saying, “I know it’s irritating to have me here,” and telling Genevieve that she was being “impatient and domineering.” But they exchanged Christmas gifts, with Barack embarrassed when Genevieve bought an expensive white Aran cable-knit wool sweater for him at Saks Fifth Avenue. When he asked her what she wanted, Genevieve suggested lingerie, which she says “threw him into an absolute tailspin” before he returned with something that Genevieve privately thought was “incredibly tame.”

A week before Christmas, Obama flew to Honolulu, and he spent much of his time in transit reading a book by Studs Terkel, most likely his newly published The Good War: An Oral History of World War II. On New Year’s Day, he wrote to Genevieve that “my trip has progressed without any notable events” but that “I was foolish to think that I’d have the time or energy to work on my writing” in Hawaii because “reacquainting myself with the family has proven to be a fulltime job … they all have used me as a sounding board for all sorts of conflicts and emotions that have previously stayed below the surface…. I’ve been the catalyst for tears, confessions, ruminations, and accusations.”

Genevieve had never met any of Barack’s family, but he offered her sketches of them all. “My mother is as I last saw her, gregarious and sensitive, although she’s undergoing some difficult changes after uprooting herself from Indonesia” to live in a visibly humble cinder-block apartment building at 1512 Spreckels Street, where she and fourteen-year-old Maya shared the two-bedroom unit 402, less than a block from Maya’s ninth-grade classrooms at Punahou.

“My grandfather,” Barack went on, now age sixty-six and retired, “appears immutable. He looks more robust than ever, even while eating donuts, smoking a cigarette, and drinking whiskey simultaneously. My grandmother is doing less well—she continues to drink herself into oblivion,” indeed “incoherence,” when not working. “Her unhappiness saddens me deeply…. It may be my helplessness in the face of her problem that angers me more than the problem itself. But she retires next year, and if the fortitude she’s channeled exclusively into her work can’t be transferred into the remainder of her life, not much life will remain.” With Maya, “I watch with joy her development into a fine person,” but being back in the all too familiar tenth-floor apartment at 1617 South Beretania meant that “ghosts of myself and others in my past lurk around every corner.”

Obama wrote that his relatives all “think I’m too somber…. My mother explains that I was normal until 14, from there went directly to 35.” Stan joked that Barack is “as mean to himself as he is to everyone else. The only difference is he likes it.” But Obama was clearly discomforted by this return to his childhood surroundings. “I have trouble fitting into these Island Ways,” he told Genevieve. Within blocks were “the apartment house where I was conceived … the hospital where I was born … and the school where I spent a third of my life.” But nonetheless “I’m displaced here, it’s not where I belong—sometimes I think my only home is on the road towards expectations, leaving what’s known, complete, behind. I no longer find that condition romantic—at times I resent it deeply—but I accept it.”

That sentence was as self-revealing as any Obama had ever written, but the contrast between “the incredible isolation of people here” in far-off Hawaii and “the nervous energy or self-consciousness you find in New York” was discombobulating. “My contradictory feeling for Hawaii reflects itself in my relationship with Bobby, who embodies the beauty and limitations of the place. He’s making a comfortable living running a concession at a local high-school, and supplements his income with cash from a few big cocaine deals he was involved with last year”—an aspect of a best friend’s life that was unobjectionable only if you viewed cocaine use itself as unremarkable.

Obama observed that Titcomb “jokes about his appetite for food and women, exhibiting a charm and flair in everything he does, but a sustained commitment or depth in nothing.” But Barack added, “He loves me and I love him, but he senses different priorities in me now,” though “I admire and envy his easy manner and fluid grace.” One day the two old friends went scuba diving two miles off Oahu, fifty feet down. On another, Ann’s mentor Alice Dewey “argued in husky tones with me and a few other of my mother’s friends over politics, sexual relations, art and the economy.” Only “after five hours and four cups of coffee” did Barack drive her home.

Alluding most likely to how they had met exactly one year earlier, Barack asked Genevieve, “How did you spend New Year’s Eve? Mine was not as eventful as the last one.” He told her he was flying back to New York on January 22 and would likely stay with Hasan and his cousin Ahmed at the Eagle Warehouse apartment “until I find a place. I confess to a fear of failing to find a useful gig for myself upon my return, but have no thoughts of doing anything else. I expect the transition may be tough on me,” as his prior attempts to obtain a politically satisfying job had failed, “but I expect you to have some patience with my foolishness and kick me when I get out of line. I miss you very much, and hope your enthusiasm for school stays high.” He signed off “Love, Barack.”

The same day Barack wrote that letter to Genevieve, his mother Ann privately recorded her own plans for the New Year. Many of her jottings concerned the multiple debts she owed her parents, including $1,764 per semester for Maya’s Punahou tuition, and $175 for an airplane ticket for “Barry.” The “$4,846 withdrawn from account by Toot” was later updated with “$3,940 repaid 2/6/85.” A long numerical “People List” began with Maya as #1, Ann’s Indonesian lover Adi Sasono #2, “Bar” #3, her parents #s 4 and 5, and included former brother-in-law Omar Obama as #175. The “Long Range Goals” she listed on New Year’s Day began “1. Finish Ph.D. 2. 60K 3. In shape 4. Remarry 5. Another culture 6. House + land 7. Pay off debts (taxes) 8. Memoirs of Indon. 9. Spir. develop (ilmu batin) 10. Raise Maya well 11. Continuing constructive dialogue w/ Barry.”

Once Obama returned on January 22, Genevieve was disappointed that having him back in her daily life was “so disruptive, instead of a sweet re-meeting.” Given how challenging teaching first grade at PS 133 was, “I actually find his interruption of my focus on school as damaging, disconcerting,” but “he’s really into travelling his path with concentrated determination as well. It is still true that I want to live alone.” Obama later wrote of refusing the offer of a well-paid job from an impressive black man who headed a New York City civil rights group and had recently dined at the White House with “Jack,” the secretary of housing and urban development. Arthur H. Barnes headed up the New York Urban Coalition, but African American New Yorker Samuel R. Pierce was HUD secretary; only four years later did Jack Kemp succeed him.

Instead Obama focused on a job ad from the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), for its Project Coordinator post at the City College of New York (CCNY) in West Harlem. NYPIRG, founded in 1973, was based on a campus chapter model first outlined in Action for a Change. A Student’s Manual for Public Interest Organizing, a 1971 book written by famous consumer advocate Ralph Nader and three coauthors, one of whom, Donald K. Ross, became NYPIRG’s initial executive director. By 1985 NYPIRG had chapters at most campuses of New York State’s two public college systems, the predominantly white State University of New York (SUNY) and the largely minority City University of New York (CUNY). Campus referenda that authorized a $2-per-student-per-semester fee provided NYPIRG’s financial base.

The project coordinator post paid only about $9,200, half of what Barack had been making at BI, and the CCNY job was open at midyear because of the departure of a young woman whose fall tenure had been unsuccessful. Yet the CCNY chapter boasted one of NYPIRG’s most experienced student leaders, Buffalo native Diana Mitsu Klos, who had moved to New York City eighteen months earlier upon being elected NYPIRG’s student board chair for the 1983–84 academic year. NYPIRG’s campus projects statewide were overseen by Chris Meyer, and 1983 Yale graduate Eileen Hershenov supervised CCNY and other Manhattan chapters from NYPIRG’s tumbledown office at 9 Murray Street in lower Manhattan. On some day in late January or early February, Obama appeared there for a job interview with Hershenov and Meyer, who were “enormously impressed” with him, particularly since NYPIRG was “desperate to diversify” its predominantly white staff, especially at such a heavily minority campus as CCNY.

Obama’s hiring was all but immediate, as CCNY’s spring semester classes began on Monday, February 4. Eileen accompanied him up to City and introduced him to Diana Klos and seven or eight other core chapter members, including Alison Kelley, who thought Obama was “very poised, very together” right from day one. The NYPIRG chapter had a small office with desks and a telephone in a homely metal trailer known as the Math Hut that sat between CCNY’s iconic Shepard Hall and the college’s low-rise administration building south of 140th Street on the east side of Convent Avenue, just across from the North Academic Center (NAC), a hulking modern gray-brick behemoth that housed City’s humanities and social science departments.