По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

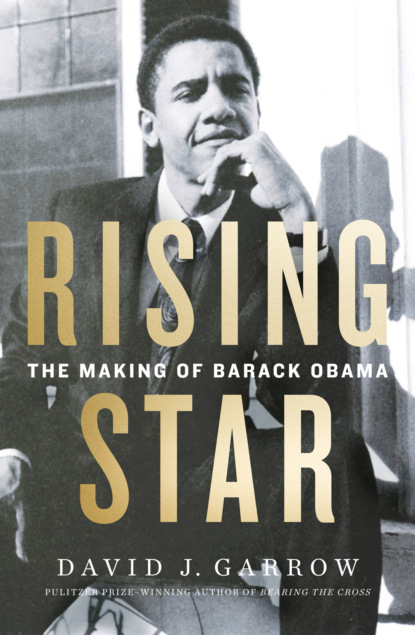

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

More than twenty years later, Barack would accurately recount how “I stopped for the night at a small town in Pennsylvania whose name I can’t remember any more, and I found a motel that looked cheap and clean, and I pulled into the driveway, and I went to the counter where there was this old guy doing crossword puzzles” who “asked me where I was headed, and I explained to him I was going to Chicago because I was going to be a community organizer, and he asked me what was that.” Then came Bob’s monologue: “You look like a nice clean-cut young man, you’ve got a nice voice. So let me give you a piece of advice: forget this community organizing business. You can’t change the world, and people will not appreciate you trying. What you should do is go into television broadcasting. I’m telling you, you can make a name for yourself there.”

“Objectively speaking, he made some sense,” Barack would reflect in that retelling. Two weeks later, he repeated the centerpiece of Bob’s monologue word for word. Thirteen months later Obama recited Bob’s message once more, as he did again five months after that. In May 2008, Obama recounted his memory of that night yet again: “You’ve got a nice voice, so you should think about going into television broadcasting. I’m telling you, you have a future there.”

In contrast to Barack’s indelible memory of their conversation, twenty-nine years later Bob Elia had no recollection of young Obama. When asked, though, he almost immediately told a caller, “You’ve got a nice voice” before launching into a ten-minute monologue on the life-extending powers of a trio of multisyllabic nutritional supplements.

But in 1985, on the next summer morning, Barack checked out of the motel without reencountering Bob, and after heading down South Hermitage Road and bearing right onto I-80, the Ohio state line was just a few miles ahead. I-80 became the Ohio Turnpike and then the Indiana Toll Road once it crossed another state line. Chicago lay six hours ahead, but as Barack Obama drove west, he was headed toward a place he really had never been, indeed toward a place he really had never known: he was heading west toward home.

Chapter Four (#ulink_92d9529c-fcd1-5915-8339-dda1eb3f5a15)

TRANSFORMATION AND IDENTITY (#ulink_92d9529c-fcd1-5915-8339-dda1eb3f5a15)

ROSELAND, HYDE PARK, AND KENYA

AUGUST 1985–AUGUST 1988

West of South Bend, the Indiana Toll Road slides southward as the shoreline of Lake Michigan draws near. The Indiana Dunes give way to Burns Harbor and its huge steel mill, which marks the eastern edge of the Calumet region’s industrial lakeshore. Gary and East Chicago offer a gritty industrial visage before the highway turns sharply north as the Illinois state line approaches. There the interstate becomes the Chicago Skyway, with the East Side, the Calumet River, and then South Chicago flashing by underneath the elevated roadway.

On Saturday afternoon, July 27, Barack Hussein Obama took the next exit heading for Hyde Park, turning northward on the broad boulevard of Stony Island Avenue. At 67th Street, Jackson Park appeared on the east side of the road, offering sunlit greenery all the way to 56th Street. Beenu Mahmood’s summer apartment at 5500 South Shore Drive was just a few blocks away.

Obama stopped at a pay phone but discovered he had miswritten Beenu’s number, and he called Sohale to get it right. Then Beenu met Barack in front of the tall luxury building, whose tenants had access to a heated swimming pool plus an on-site deli—“not exactly the setting I had envisioned for launching my career as selfless organizer of the people,” Barack wrote Genevieve a few days later. “The discordance only increased when we went to a fancy outdoor café downtown to feast on barbecued ribs.”

Beenu’s fiancée, Samia Ahad, was in Chicago too, and after a restful Sunday Barack drove south to Roseland on Monday morning, while Beenu headed to Sidley & Austin’s downtown office. At Holy Rosary’s rectory, on 113th Street across from the sprawling Palmer Park, Barack met his Calumet Community Religious Conference and Developing Communities Project coworkers. Mike Kruglik, he wrote Genevieve, “reminds me of the grumpy dwarf in Snow White” with “a thick beard and mustache. He speaks with the blunt, succinct clip of working class Chicago.” That first day “he barely acknowledged my presence” but as the week went on it became clear that Mike is “both competent and warm.” Adrienne Jackson was “prim,” “helpful and committed,” with “polished administrative skills,” and Obama quickly determined that she, like himself, had been “hired as much to give the staff a racial balance as she was for her abilities.” Of Jerry Kellman, Barack told Genevieve, “In his rumpled, messy way, he exhibits a real passion for justice and the concept of grassroots organizing. He speaks softly and is chronically late, but is real sharp in his analysis of power and politics, and is also disarmingly blunt and at times manipulative. A complicated man … but someone from whom I expect I can learn a few things.”

Obama also wrote that he “made full use of the amenities” that Beenu’s building offered “without guilt.” Samia was on her way to becoming a professionally acclaimed chef, and one evening she cooked a Pakistani dinner; Beenu’s friend Asif Agha joined them, even though the apartment had no dining table or chairs. Asif, like Beenu, had graduated from the famous Karachi Grammar School before receiving his undergraduate degree from Princeton University. He was the same age as Barack, and he had arrived in Hyde Park two years earlier to begin graduate study in languages reaching from Greek to Tibetan, under the auspices of the University of Chicago’s interdisciplinary Committee on Social Thought. With Beenu about to return to Manhattan for his third year at Columbia Law School, Asif was another smart and outgoing member of the Pakistani diaspora that had provided Barack’s closest male friends for the past six years.

Tuesday morning Barack discovered that he had left his car lights on all night, and he needed a jump start so he could meet his day’s schedule. Wednesday morning the car again failed to start, and Beenu, Samia, and Asif all helped push it to get it going. A deeply embarrassed Barack confessed to Genevieve that “I appeared to have left my brains back in N.Y.” because “similar lapses have repeated themselves.” By the next weekend, he had signed a lease for a small $300-a-month studio apartment, #22-I, at 1440 East 52nd Street, in the heart of Hyde Park. He also told Genevieve about the “pang of envy and resentment” he felt toward Beenu’s “prestigious, well-paying and basically straightforward work as a corporate lawyer” and how it contrasted with his far more precarious existence.

Down in Roseland, Kellman’s first goal was to teach Obama community organizing’s defining centerpiece, the one-on-one interview, or what IAF traditionalists called “the relational meeting.” All Alinsky-style organizing recognized the cardinal principle that first “an organizer has to … listen—a lot.” According to Industrial Areas Foundation veteran and United Neighborhood Organization adviser Peter Martinez, the ability to listen is the “critical skill,” for it enables an organizer “to synergize all of the things that they’re experiencing so that they can incorporate that into their thinking in a way that when they talk with people, people can hear themselves coming back within the structure of what it is you’re suggesting might be done.” This, Martinez said, would keep people from feeling like the organizer is putting something “on top of them.”

Kellman knew the first month was “very crucial” with any new recruit, and particularly with someone who “had never encountered blue-collar and lower-class African Americans.” During Obama’s first few days, Jerry took him along so that Barack could watch a veteran organizer ask people to talk about their lives and to say what they thought were the community’s problems, listening especially for how that person’s own self-interest could motivate them to take an active part in DCP. Obama “struggled with this in the beginning,” Kellman recalled, as his connections with people “could be superficial,” and “I would challenge Barack to go deeper, to connect with their strongest longings.” But Jerry was too busy to do this full-time, and so “very quickly he was out on his own, just talking to people, day after day,” with the expectation that each week Barack could conduct between twenty and thirty such one-on-ones with pastors and parishioners from DCP’s Roman Catholic churches. Among the first pastors Obama called upon were Father Joe Bennett at St. John de la Salle, the church that Adrienne Jackson attended, Father Tom Kaminski at St. Helena of the Cross, and Father John Calicott at Holy Name of Mary—who had been so responsible for Jerry’s ad in Community Jobs. Bennett remembered Barack asking him “all kinds of questions,” and when he left Bennett thought “what a sharp, brilliant young man.”

Kellman also took Obama on a driving tour of the neighborhoods DCP and CCRC serviced. More than two decades later, Barack could spontaneously describe what he saw when Jerry drove east on 103rd Street past Trumbull Park before turning south on Torrence Avenue. “I can still remember the first time I saw a shuttered steel mill. It was late in the afternoon, and I took a drive with another organizer over to the old Wisconsin Steel plant on the southeast side of Chicago…. As we drove up … I saw a plant that was empty and rusty. And behind a chain-link fence, I saw weeds sprouting up through the concrete, and an old mangy cat running around. And I thought about all the good jobs it used to provide.” As Kellman had told him, “when a plant shuts down, it’s not just the workers who pay a price, it’s the whole community.”

The people of South Deering had been living for more than five years with what Obama saw that afternoon. “The mill is just like a ghost hanging over the whole community like a cloud,” one St. Kevin parishioner explained, indeed “the ghost of the Industrial Revolution,” another resident realized. “It just sat there and rotted before everyone’s eyes,” Father George Schopp explained, and a beautifully written article in the August issue of Chicago Magazine—one that would have made a memorable impression on any aspiring young writer who read it—described South Deering in the summer of 1985 as “the essence of the Rust Belt … along Torrence near Wisconsin Steel, the stores are empty; only a few taverns remain.”

Kellman also took Obama southward from Roseland, to show him the brick expanse of Altgeld Gardens, which was so distant from all the rest of Chicago apart from the huge Calumet Industrial Development (CID) landfill just to the east where all of the city’s garbage was dumped, and the Metropolitan Sanitary District’s 127 acres of “drying beds” for sewerage sludge just north across 130th Street. Neither the dump nor the sewer plant ever drew much attention, yet just to the northeast, near the older Paxton Landfill, as Chicago Magazine’s Jerry Sullivan wrote, “the greatest concentration of rare birds in Illinois” was spending the summer “squeezed between a garbage dump and a shit farm.”

Obscure scientific journals with names like Chemosphere occasionally published studies that detailed how the presence of airborne PCBs was “significantly higher” around “the Gardens” than anywhere else in Chicago, but just a week after Obama’s introductory tour of the area, an underground fire at an abandoned landfill abutting Paxton—a weird and unprecedented event—drew camera crews, reporters, and city officials to the Far South Side’s toxic wasteland. The chemical conflagration took more than twelve days to finally burn itself out, and region-wide press coverage featured UNO’s Mary Ellen Montes criticizing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for its lack of interest. City officials suggested blowing up the remaining metal drums with unknown contents, and UNO filed suit in federal court against the EPA in hopes of jarring federal officials into action.

In Roseland, more than a mile northwest of the underground fire, the only newsworthy event in the eyes of Chicago newspapers during Barack’s first weeks was the arrest of an initial suspect in a cold-blooded killing that was all too reminiscent of Ronald Nelson’s murder just five months earlier. One Saturday evening, shortly before Barack’s arrival, forty-nine-year-old factory foreman Enos Conard and his twenty-three-year-old son were manning an ice cream truck on 105th Street, hardly five blocks from Father Tom Kaminski’s St. Helena Church. Two men in their early thirties approached and ordered ice cream before one suddenly drew a gun. As Conard reached for his own weapon, the lead assailant fired a single fatal shot into Conard’s chest. Conard left behind a widow and four children, and a fellow vendor complained to reporters that “so many people have guns.”

A mortician from nearby Cedar Park Cemetery had drawn press attention by publicizing his offer of free funerals and burials to victims of Far South Side gun violence, and Conard’s family became the seventh to accept. In late August, police arrested L. C. Riley of Roseland as one of the assailants, and two years later both Riley and triggerman Willie Dixon, also from Roseland, were convicted of Conard’s murder. Dixon was sentenced to life in prison, and three decades later, Dixon remained in the same cellblock at Stateville Correctional Center as Nelson’s killer, Clarence Hayes.

Also in Roseland, although invisible to Kellman and Obama, ACORN’s Madeline Talbott had hired a new organizer, Ted Aranda, who had worked previously for a year under Greg Galluzzo at UNO, to revitalize ACORN’s Far South Side presence after months of inactivity following Steuart Pittman’s departure in mid-March 1985. Unlike CCRC’s and DCP’s church-based organizing, ACORN went block by block knocking on doors to get residents together to tackle community problems. Aranda explained years later that “most of the people that I got involved in the organization were always women.” The goal was to attract enough recruits to hold a community meeting, and Aranda’s Central American heritage was a significant asset, because his dark complexion led most Roseland residents to assume he was African American. “That’s not my identity” once “you look beyond my skin color,” Ted said, but he also had an advantage in Latino neighborhoods, where “they took me for a Hispanic.”

Aranda learned that Roseland residents were angry that the city had not provided them with garbage cans, and Pullman people were upset about a disco patronized by gang members. By early September, the Roseland group, COAR—Community Organized for Action & Reform—had drawn enough interest that Talbott convened a meeting at King Drive and 113th Street—i.e., Holy Rosary. In late October, the Pullman group, ERPCCO—East Roseland Pullman Concerned Citizens’ Organization—succeeded in closing the disco. But by the winter, Ted Aranda “became disenchanted with community organizing as a viable model for radical change,” and he resigned. By the standards of Alinsky-style organizing, Aranda’s months in Roseland had been successful, but as he explained years later, he “was more convinced than ever by the end of my short organizing stint that the political system itself was the problem.” And even though COAR and DCP were working in the very same neighborhood, “Barack Obama I never met at all.”

DCP’s board met on the second Tuesday evening of each month, and at the August meeting in St. Helena’s basement, Kellman introduced Obama so the members could formally ratify his hiring. Virtually everyone was taken aback by how youthful he seemed. “My first thought was ‘Gee, he is really young,’ ” Loretta Augustine recalled years later, and she whispered that to Yvonne Lloyd sitting next to her. Yvonne’s first reaction was just like Loretta’s: “We had children older than he was.” The always outspoken Dan Lee said aloud what they all were thinking: “Whoa, this is a baby right here.” Obama smiled and acknowledged that he looked young, but once he spoke to them about himself and responded to their questions, he quickly won them over.

“He was very candid in his answers—straightforward,” Loretta remembered. “The impressive part was that he seemed to really understand what we were saying to him,” which she considered a marked change from both Mike and Jerry. “When we talked about certain things that he didn’t know about, he didn’t lie. He basically said, ‘You know what, I’m not really familiar with that. However, these are things that we can learn together.’ ” In short order, “we knew he was the right person for us,” Loretta recalled, and though “his honesty has a lot to do with it,” so did Barack’s appearance. “His color did make a difference to us, because it’s important for us and our children and everybody else to understand that people who look like us can do the job.”

The day after that meeting, Barack wrote the letter to Genevieve that described his trip from New York—and his unforgettable conversation with Bob Elia at the Fairway Inn—as well as his first weeks in Chicago. Genevieve had called Barack several days earlier, and he began by apologizing for “my phone manner. You know I dislike the telephone…. Combined with the lingering pain of separation, I’m sure I sounded guarded and stand-offish. I’m better with letters … (yes, more control).” Barack said that Jerry “has thrown me into” several neighborhoods, including Altgeld Gardens and Roseland, “without much … guidance” at all. “There are some established leaders with whom I can work, but I must say that for now, I’m pretty confused and feel my inexperience acutely.” He realized that having “a trustworthy face” worked to his advantage, as did “the dearth of educated young men in the area who haven’t gone into the corporate world.” Barack was pleased with the job, but questions remained. “For all the kindness and helpfulness the communities have offered me so far, I can see the thoughts running through their heads—‘another young do-gooder.’ I know it runs through mine.” So “doubts of my effectiveness in such a setting remain, but at least I feel like I’m in one of the best settings to really test my values that I could hope to find right now.”

Overall, “the work offers neither more nor less than I had anticipated,” which he found reassuring. He characterized Hyde Park as “a poor man’s Greenwich Village,” but he was pleased with his apartment and “the cheap prices in restaurants” though not “the disappointing newspapers.” But another contrast from New York was more striking. “Blacks seem more plentiful, and more importantly, seem to exude a sense of ownership, of comfortable dignity about who they are and where they live than do blacks” in New York. Chicago offered “a much more visible well-to-do and middle class black population who still live in a cohering black community,” and “black culture here is more closely rooted to the South; the neighborhoods have a down home feel…. Even the poorest black neighborhoods seem to have a stronger social fabric on which to rely than in NY” and “as a result, the young bucks, though no less surly and pained than their NY counterparts, appear to feel less need to constantly assert themselves against the respectable, and in particular, the white, world.” Obama wondered whether “these strands of self-confidence” were due to Mayor Harold Washington, whose “grizzled, handsome face shines out from many store front windows in the areas I work.”

Barack wrote that he already had swum in Lake Michigan, but confessed “the almost daily thump in my chest, pain and longing when I think of Manhattan, and the Pakistanis, and when I think of you.” He wrote out his address and phone number and told Genevieve, “I expect you to make use of this information frequently.” He enclosed a $130 check for money he owed her, and closed by telling her about his African sister who had canceled her trip to New York ten months earlier at the last minute: “Auma did get in touch with me and will be coming through Chicago in two weeks. Very excited.”

By late summer 1985, Auma Obama was still in university at Heidelberg, but her closest German friend was now studying at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, a small town southeast of St. Louis, Missouri, which was far from Chicago. Auma traveled to Carbondale for two weeks, calling Barack once to update him on her plans, and then took a long train trip to Chicago, where he met her at the station and then cooked a South Asian dinner for them in his small apartment, where Auma would bunk on the living room couch. Obama was eager to have his sister tell him about their late father, and for the next ten days—interrupted only by his work—the siblings spoke for long hours about Barack Hussein Obama Sr. One day Auma went with him to work at Holy Rosary, where she met Jerry and several parish volunteers. Back in Hyde Park, one evening Auma went beyond her somewhat-edited comments about Obama Sr. and told her brother that he had been fortunate not to have grown up in his father’s household, particularly after Obama Sr. married Ruth. Auma showed family photos to Barack, but she also spoke about Obama Sr.’s drinking problem and the suffering his older children endured as a result of his financial irresponsibility, Roy Abon’go even more than her. Auma also mentioned “the old man’s” auto accidents and job-loss experiences, and told Barack, “I think he was basically a very lonely man.” Barack generally said little in response, but he took time to show Auma Chicago’s downtown sights and museums before the Carbondale friend and her boyfriend arrived in Chicago to take Auma with them to Wisconsin. Before she left, Auma urged Barack to visit her once she returned to Kenya.

Auma later remarked that the visit was “a very intense ten days together” and that “I was very conscious of trying to give him a full picture of who his father was.” In the immediate aftermath of her visit, Barack said little about the new and sad portrait Auma had painted of Obama Sr. to his coworkers or to his only regular outside-work acquaintance, Asif Agha. Barack and Asif had drinks and dinner almost every Thursday night at a restaurant on 55th Street in Hyde Park. “We hit it off … and we saw each other extremely regularly,” Agha recalled years later. “He didn’t know anyone” beyond DCP, and it was obvious that “the work was stressful, and he was discovering himself.” Barack did not talk much about DCP to Asif. “The only person he ever told me much about” was fellow Princeton graduate Mike Kruglik, whom Obama clearly liked. “He came up frequently.” Mostly the two twenty-four-year-olds talked about writing. “I used to write poetry, and he used to write short stories,” and each Thursday “we would share whatever we had been writing.” According to Asif, Barack “was very serious about writing” and regularly turned out short sketches of six to ten double-spaced typed pages, but there was no real suggestion that he would pursue writing as a career. These dinners were sometimes leavened with shots of tequila, giving Obama at least one regular outlet from the stresses and strains of being a real organizer.

A decade later, Obama offered a sketch of Auma’s visit that had her arriving at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, not Union Station, but that did describe her telling him about their father’s tragic latter years. “Where once I’d felt the need to live up to his expectations, I now felt as if I had to make up for all of his mistakes.” Another decade later, during the first six months of his emergence as a nationally known figure, Obama several times opened up about his recollections of Auma’s visit. “Every man is either trying to live up to his father’s expectations or making up for his mistakes,” he told one questioner. “In some ways, I still chase after his ghost a little bit.”

In a long interview with radio journalist Dave Davies, Obama spoke more extensively about his father than at any other time in his life, stating that during Auma’s visit, he learned that his father had had “a very troubled life.” He understood that some of Obama Sr.’s employment problems had occurred “in part because he was somebody who was willing to speak out against corruption and nepotism” within the Kenyan government, but the portrait his mother had so insistently painted “of this very strong, powerful, imposing figure was suddenly balanced by this picture of a very tragic figure who had never been able to really pull all the pieces of his life together.” What Auma had told him was “a very disquieting revelation” that really “shook me up” and “forced me to grow up a little bit.” While “in some ways it was liberating” relative to the implicit expectations Ann’s glowing comments plus Obama Sr.’s own self-presentation to his ten-year-old son back in December 1971 had created, “it also made me question myself in all sorts of ways” because “you worry that there are elements of their character that have seeped into you … and you’ve got to figure out how you’re going to cope with those things,” particularly how Obama Sr. had behaved toward women and the offspring he sired.

Asked on camera by Oprah Winfrey about his father, Obama said, “he ended up having an alcoholism problem and ended up leading a fairly tragic life.” When a friend asked Barack to quickly compose some uplifting advice for young black men, Obama e-mailed that “none of us have control of the circumstances into which we are born” and that some will have to “confront the failings of our own parents.” But “your life is what you make it.” A few years later, Barack admitted that “part of my life has been a deliberate attempt to not repeat mistakes of my father,” whom he acknowledged “was an alcoholic” and “a womanizer.” Obama acknowledged that Auma had revealed how their father had “treated his family shabbily” and had lived “a very tragic life.” Even though Barack did not speak about this disquieting news to Asif, Mike, or Jerry, the long-term impact of Auma’s truth telling would be profound. “This was someone who made an awful lot of mistakes in his life, but at least I understand why.”

In early September 1985, Chicago’s public school teachers went on a citywide strike. It was the third straight fall, and the eighth in eighteen years, that school days were lost to a labor dispute. The Chicago Teachers Union was demanding a 9 percent pay raise and the city had offered 3.5 percent; only 14 percent of union members had actually participated in the strike vote. Independent observers, such as education researcher Fred Hess, told reporters that both sides were being unreasonable, and a Chicago Sun-Times editorial described the union’s behavior as “unconscionable.” Quick intervention by Illinois governor James R. Thompson led to a 6 percent settlement and the loss of only two school days.

That fall, Jerry Kellman was still savoring the triumph he had experienced in early July when the Illinois legislature appropriated $500,000 to fund a computerized CCRC jobs bank that would assess unemployed workers’ skills and market their résumés to potential employers. The big pot of money had been obtained by Calumet City state representative Frank Giglio, a close friend of Fred Simari, the St. Victor parishioner who had been volunteering virtually full-time for Kellman, as well as Hazel Crest state senator Richard Kelly.

The half-million dollars would allow Governors State University (GSU) to hire twenty job-skill-assessment interviewers for ten months to create résumés for unemployed individuals. In news articles about this, Kellman said the program’s success was dependent upon “hundreds” of volunteers stepping forward and pressing employers to hire those workers. Once the funding was confirmed, Jerry made plans to shift Adrienne Jackson to help oversee the new program and began aiming for a massive public rally to kick off the enterprise. Before the end of August, he hired Sister Mary Bernstein, a forty-year-old Catholic nun and experienced organizer, and assigned her to St. Victor to handle CCRC’s Catholic parishes in the south suburbs. In tandem with Mike Kruglik and DCP, the immediate goal was to mobilize as large a crowd as possible for the kickoff rally Kellman scheduled for Monday evening, September 30, a day before the program office at GSU would open officially.

Kellman arranged for the two most powerful individuals in Illinois—Governor “Big Jim” Thompson and Archbishop Joseph Cardinal Bernardin—to speak at the event. Choirs from Joe Bennett’s St. John de la Salle and John Calicott’s Holy Name of Mary would perform, and the invaluable Fred Simari would preside as master of ceremonies. Also featured on the podium would be Lutheran bishop Paul E. Erickson, Methodist bishop Jesse DeWitt, Presbyterian executive Gary Skinner, and the towering young Maury Richards from United Steelworkers Local 1033, whom advance press reports described as “president of the state’s largest”—they might have added “remaining”—steel workers local.

Five days before the rally, the food processor Libby, McNeill & Libby announced that within the next year, it would close its Far South Side Chicago plant on 119th Street; that meant a loss of 450 good jobs. The Sunday before the rally, Leo Mahon praised his St. Victor parishioners like Fred Simari and Gloria Boyda for the time they gave to CCRC’s employment efforts and reminded his congregation that scripture teaches that “the desire for money is the root of all evil.”

On Monday evening, CCRC vice president Rev. Thomas Knutson hosted a pre-rally dinner for the almost two hundred program participants at his First Lutheran Church of Harvey before the 8:00 P.M. rally kicked off at nearby Thornton High School. A racially diverse crowd of more than a thousand, including a watchful Barack Obama and dozens of people from DCP’s Chicago parishes, filled the gymnasium as Fred introduced the speakers, including Loretta Augustine on behalf of DCP. After Maury Richards told the audience, “we’ve lost forty thousand jobs in the past few years,” the governor came forward and began by saying, “My name is Jim Thompson. My job is jobs.” He went on to declare that “jobs are more important than mental health or law enforcement, because unless people are working and paying taxes, there won’t be any resources to pay for those services.”

But the evening’s real star was Cardinal Joe Bernardin, who denounced racism and called for “cultural and ethnic unity in the Calumet region.” He noted how unemployment “cuts across racial and ethnic lines,” and he promised that “the church is here to help you” while stressing that “the real leadership must come from the laity.” Sounding at times like Leo Mahon, Bernardin declared that “every person has a right to a decent home” and vowed that “the cycle of poverty can be broken and community decline can be turned around.” The archbishop pledged further church support for CCRC, and the rally ended with a white female parishioner from Hazel Crest asking the crowd: “Do you want to be part of a community that controls its future?” The audience responded with lengthy applause.

For Obama, the rally and the bus ride back to Holy Rosary provided an opportunity to make some new acquaintances, such as Cathy Askew, who had sat quietly through their introductory meeting at St. Helena. He was also able to talk more with the dynamic Dan Lee, DCP’s board president, and with Dan’s fellow deacon at St. Catherine, the vigorous Tommy West. For Jerry, Fred, Gloria, and most of all Leo Mahon, the rally was a wonderful culmination of their efforts that reached back over five years. Harvey Lutheran pastor Tom Knutson described the rally as “a tremendous experience for the local community.”

Now CCRC’s challenge was to get the new “Regional Employment Network” (REN) up and running. GSU planned to have some skills assessors ready to begin interviewing unemployed individuals by early November, but in early October news broke that an Allis-Chalmers engine plant and an Atlantic-Richfield facility would soon be closing, costing up to nine hundred more good jobs.

Kellman privately had been told a few days before Bernardin’s appearance that the national Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CHD) would be awarding CCRC an additional $40,000 to support the REN program, with an event on Saturday, October 26, marking the public announcement. Obama joined Kellman at the ceremony, and a story in Monday’s Chicago Tribune marked his first appearance in the Chicago press: “Barack Obama, who works with the Calumet Community Religious Conference, said its grant will be used to assess skills of unemployed workers and to aid them in finding jobs.” The first actual assessment sessions kicked off at St. Victor in Calumet City on November 14 and 15, attracting eighty-six applicants ranging in age from nineteen to sixty-seven years old. Six skills assessors prepared a fourteen-page information sheet on each applicant, and Adrienne Jackson wishfully told a local reporter, “There are hundreds of employers out there who need people.” She predicted that REN would interview more than thirteen thousand job seekers during the next eight months.

Looming most dauntingly was the future of LTV’s East Side Republic Steel plant, where the thirty-three-hundred-person workforce included twenty-four hundred members of Maury Richards’s United Steelworkers Local 1033. Since midsummer, LTV executives had been demanding tax abatements from Governor Thompson and Mayor Harold Washington; the city had responded with proposed investment incentives, as the East Side plant, just like Wisconsin and South Works before it, desperately needed significant modernization if there was any chance of long-term survival. LTV had more than $2 billion in debt, had lost more than $64 million in 1984, and its losses for 1985 could be triple that figure. Richards told reporters the only way to save aging U.S steel plants was a commitment from the federal government.

Frank Lumpkin told a congressional subcommittee that the underlying issue was more fundamental: “jobs or income is the basic human right, the right to survive.” Throughout the late summer of 1985, Frank had been writing to Chicago’s daily papers, saying that unemployed workers “are fed up with programs for training and retraining when jobs don’t exist and with job search programs that only provide employment for those who run them.” His bottom-line demand was clear: “the federal government must take over and run these mills—nationalize them—for the good of our country and our community.”

In the Chicago Tribune, Mary Schmich profiled former Local 65 president Don Stazak, who now worked as toll collector on a nearby interstate rather than for U.S. Steel. “I thought of the company as a father,” he told Schmich. In early November, Maury Richards and his 1033 colleagues decided that their situation was so dire that previously full-time officers like the local’s president would return to work in the mill rather than draw union paychecks.

In late September, Obama got news that was almost as disquieting as Auma’s revelations about their father: Genevieve wrote to confess that she had become sexually involved with Sohale Siddiqi. Soon after Barack’s late July departure for Chicago, Genevieve had flown to San Francisco to visit a friend before returning to New York on August 14. That evening she and Sohale “went to a Bonnie Raitt concert together and did ecstasy, that’s what did it,” she later recounted. Her own struggles with alcohol had not improved in the wake of Barack leaving and with the beginning of another school year at PS 133, yet Barack thanked her for “your sweet letter” when he wrote back to her. “The news of Sohale and you did hurt … in part because I was the last to know—the Pakis were sounding awfully stiff the last time I spoke to them. But mainly the hurt was a final tremor of all the mixed-up pain I had been feeling before we parted—watching something I valued more than you may know pass from what is, what might still be, to what was.”

But Barack’s first two months in Chicago leavened his heartache. “It seems that we have both ended up where we need to be at this stage in our lives,” so while “the pain of your absence is real, and won’t lessen without more time, I feel no regrets about the way things have turned out.” He ended by saying he hoped to get back to New York sometime in the months ahead. “All my love—Barack.” Reflecting back years later on what had transpired, Genevieve mused that Barack was probably “very disappointed with me,” for given Siddiqi’s dismissive attitude toward life, Barack no doubt “thought Sohale was an empty shell for a man.”

In Chicago, Barack’s work environs offered him better opportunities for self-reflection than his once-a-week reimmersion in the easy camaraderie of the Pakistani diaspora when he met up with Asif Agha. Jerry Kellman’s invaluable sidekick Fred Simari saw Barack at Holy Rosary almost every weekday that fall. Simari recalled Obama as “quiet, laid back,” “extremely bright,” and as someone who “seemed like he really studied everything.” Father George Schopp had the same impression: Barack was in “learning mode,” just “watching and reflecting.” In addition to his daily work discussions with Jerry, Mike, and Mary Bernstein, Barack also interacted with Holy Rosary secretary Bonnie Nitsche and the parish’s most committed volunteer, Betty Garrett. “We took him as our son from jump street,” Betty said of herself and Bonnie. The two regularly pestered Barack and Holy Rosary’s forty-one-year-old pastor, Bill Stenzel, about their cigarette smoking, which was allowed indoors only in the rectory’s kitchen. This addiction brought Barack and Bill together more than would otherwise have been the case, but that fall Obama also visited every week with St. Helena’s forty-five-year-old Father Tom Kaminski. Like Leo Mahon and George Schopp, Bill and Tom were both progressive and challenging priests, men whose religious faith accorded far more closely with Joe Bernardin’s Catholicism than with the hierarchical, top-down archdiocese that John Patrick Cody had ruled. Bonnie Nitsche and her husband Wally thought that Bill’s strong but gentle spirit made Holy Rosary’s small multiethnic congregation into “a microcosm” of what a community would be if you “got rid of prejudices.” The rectory “was like one big office,” Bill remembered, with the organizers on one side of the first floor, and Bill and Bonnie on the other.