По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

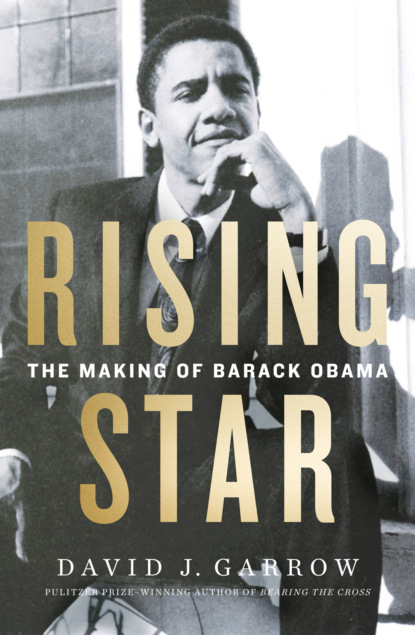

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In August, Maria Cerda, the director of the Mayor’s Office of Employment and Training (MOET), finally appeared at a community meeting in Altgeld Gardens to respond to DCP’s request that MOET open an office within reasonable travel distance of the Gardens. Obama had prepared Loretta Augustine to chair the meeting, but almost immediately, Cerda became “very aggressive and domineering,” according to Loretta. “I was supposed to introduce the issue, and she tried to take over,” and became openly patronizing, asking Loretta, “Do you even know what we do?” Then, from the back of the room, came Barack’s voice: “Let Loretta speak! We want to hear what Loretta has to say!”

Obama was determined to avoid another breakdown like the Zirl Smith session, so he put aside his own rule about remaining quietly in the background, and this time intervened forcefully if anonymously. Loretta remembered that “people kind of picked it up,” chanting “Let Loretta speak!” In the end, Cerda agreed that MOET would open an office on South Michigan Avenue in central Roseland, a ten-minute bus ride from the Gardens, before the end of November.

By midsummer, Greg Galluzzo and Mary Gonzales were expanding UNO’s reach by linking up with and reactivating the Gamaliel Foundation, founded in the 1960s but long dormant. Greg had been seeking funding for this new vision since early 1986, and he believed that Gamaliel could serve as a training institute that would “generate a flow of leadership for the city’s future.” Mary and Greg saw community organizing as “the way people can move from a sense of helplessness and isolation to active participation in the decisions affecting their lives.” Greg felt that Chicago’s vibrant “movement” activity in earlier years had “distracted people” from pursuing long-lasting change. “Compared to the work of real community organizations, movement activity is much less grounded in communities,” he wrote. By September Greg had raised almost $100,000 for Gamaliel, with the two largest grants—$40,000 and $30,000—coming from the Joyce Foundation and the Woods Fund.

Within UNO, Danny Solis and Phil Mullins wanted to train the parents of Chicago public school students: “Improving the quality of education in Chicago is the city’s greatest challenge and clearest need.” Citing the research of Fred Hess on Chicago dropout rates, Gamaliel noted how “students are simply not prepared to handle high school classes.” By 1986, that represented a bigger problem than ever before. “Ten years ago in S.E. Chicago, a student at Bowen High School could drop out of school and get a job in the steel mills making more money than their teachers.” That world was gone, and “the major obstacle” to improving outcomes for current students “is the ineptness and mismanagement at the Board of Education level.”

Like IAF, Gamaliel would do trainings, and in early August, a one-week course for sixty community group members took place at Techny Towers, a suburban retreat center owned by the Society of the Divine Word. Obama, having the full IAF training to his credit, delivered a presentation there one day, and among those in attendance was Mary Ellen Montes. “Everyone was awed by Barack,” Lena remembered. “I was getting divorced,” and as a single mother with three children, she now had a full-time job at Fiesta Educativa, an advocacy group for disabled Hispanic students. She was immediately taken with the young man three years her junior. “Barack was extremely charismatic,” and she wanted to see more of him. “We talked quite a bit after I met him at Techny Towers,” and with Sheila Jager in California visiting her family, Barack and Lena spent a number of late-summer evenings together in Hyde Park.

“We went out to eat a few times” and “we just enjoyed talking to each other,” Lena recounted. “He was a lot of fun to talk to and we really enjoyed each other’s company.” Obama would remember some intense making-out, while Lena explained, “I’m a passionate person.” What she termed “the relationship/friendship that we had” became a close one as Barack became part of the UNO–Gamaliel network. Greg Galluzzo believed that “the continuing development of community organizing as a profession is mandatory,” and with Gamaliel often bringing its organizers together, Barack and Lena were now professional colleagues as well as intimate friends.

Obama had been in Chicago for more than a year, and it had been a more challenging and instructive period than any other of his life. He had learned a great deal about others and himself. He had bonded with Mike Kruglik, Bill Stenzel, and Tom Kaminski, as well as with DCP leaders, such as Loretta Augustine, Dan Lee, and Cathy Askew. He had also made two good friends around his age: Asif Agha and Johnnie Owens. But more changes were coming.

Jerry was shifting his focus to Gary, after being bruised by the failure of his Regional Employment Network, which could not claim to have placed even one unemployed worker in a meaningful new job. Given what was now transpiring at LTV’s East Side mill and at South Works, jobless workers on Chicago’s Far South Side faced even dimmer prospects for employment in the immediate future. Obama later wrote that Kellman had told him that CCRC’s region-wide aspirations, like DCP’s highly disparate neighborhood composition, were fundamentally ungainly and that he “should have known better.” Jerry asked Barack to come with him to Gary, but Barack said no: “I can’t just leave, Jerry. I just got here.” Kellman warned him, “Stay here and you’re bound to fail. You’ll give up organizing before you give it a real shot,” but Barack stood firm. He saw a fundamental human difference between them. Barack in twelve months had established meaningful emotional bonds with half a dozen or more colleagues, while Jerry, as Obama later wrote, had “made no particular attachments to people or place during his three years in the area.”

Obama also made a personal decision that was unlike anything he ever suggested to Genevieve: he asked Sheila Jager to move in with him. “It all seemed to happen so fast,” she later explained. Earlier in the summer, Barack had renewed his one-year lease on his studio, but it was too small for two people. Johnnie Owens was living with his parents and looking for a place, so Barack suggested he sublet the studio. Sheila had no support apart from her graduate fellowship, but Barack offered to cover the $450-a-month cost of apartment 1-N at 5429 South Harper Avenue, a quiet, tree-lined block of three-story brick buildings.

Sheila thought it was “really spacious,” with a living room, an open study, “a good-sized bedroom,” and a large, eat-in kitchen. “I thought it was a bit plush for a struggling couple,” but with Barack’s $20,000 salary and $100 a month from Sheila toward food and shopping, by early October the young couple had set up house. Barack continued to see both Asif and Johnnie regularly, with Barack taking Johnnie to see a fall exhibit featuring the work of French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Soon after moving in with Sheila, Barack tardily responded to a letter and short story Phil Boerner had sent him. Barack confessed to feeling older, or at least overextended. “Where once I could party, read and write, with a whole day’s worth of activity to spare, I now feel as if I have barely enough time to read the newspaper.” He counseled Phil about writing fiction, recommending that he focus on “the key moment(s) in the story, and build tension leading to those key moments.” He also suggested that Phil “write outside your own experience,” because “I find that this works the fictive imagination harder.” Barack spoke of thinking about and missing Manhattan, “but I doubt I’ll be going back.”

Then he introduced Sheila. “The biggest news on my end is that I have a new girlfriend, with whom I now share an apartment. She’s half-Japanese, half-Dutch, and is a Ph.D. candidate” at the University of Chicago. “Very sweet lady, as busy as I am, and so temperamentally well-suited. Not that there are no strains; I’m not really accustomed to having another person underfoot all the time, and there are moments when I miss the solitude of a bachelor’s life. On the other hand, winter’s fast approaching, and it is nice to have someone to come home to after a late night’s work. Compromises, compromises.”

Obama’s pose that fear of cold temperatures underlay his desire that Sheila and he live together downplayed his own decision and initiative. Then he updated Phil on how DCP was now becoming a freestanding organization, “which gives me no one to directly answer to and control over my own schedule. But the downside is that I shoulder the responsibility of making something work that may not be able to work. The scope of the problems here—25 percent unemployment; 40 percent high school drop out rate; infant mortality on a par with Haiti—is daunting; and I often feel impotent to initiate anything with major impact. Nevertheless, I plan to plug away at it at least until the end of 1987. After that, I’ll have to make a judgment as to whether I’ve got the patience and determination necessary for this line of work.”

The breakup of CCRC, with DCP and the South Suburban Action Conference (SSAC) taking its place, coincided with Leo Mahon leaving St. Victor. He had announced seven months earlier his September departure, and he had felt his energy flagging before that. In one of his last pastoral letters, Leo addressed the LTV and South Works news in words that echoed across the previous six years. “Catholic social teaching insists that the workers have first right to the fruits of their labor,” in line with “the Christian principle that workers, not money, come first.” Corporations should put “human concerns ahead of profit and dividends,” but LTV and U.S. Steel had made “clear that power and profit are both more important than people and jobs.” Leo’s advice was the same as in 1980: “let us translate our concern and our outrage into protest and into political action.”

Following Kellman’s shift to Gary, Greg Galluzzo took on a formal mentoring role to Obama by becoming DCP’s “consultant.” He introduced Barack to a young tax attorney, Mary-Ann Wilson, who at no charge—“pro bono”—would handle the state and federal paperwork necessary to establish DCP, like UNO before it, as an independent, nonprofit corporation.

Illinois, like the Internal Revenue Service, required a bevy of forms and submissions that Barack and DCP members would spend a good portion of that fall completing and signing. A set of bylaws was copied and updated from an earlier version Kellman had drafted in 1984. Illinois articles of incorporation required three directors—Dan Lee, Loretta Augustine, and Tom Kaminski were named—as well as a registered agent. Barack, as “project director,” left blank the space asking for his middle name. A separate, full-fledged board of directors listed Dan as president, Loretta as vice president, and Marlene Dillard as treasurer, along with everyone who was active in DCP: Cathy Askew, Yvonne Lloyd, Nadyne Griffin, Eva Sturgies, and Aletha Gibson, plus several women who had signed in at a meeting or two but not reappeared.

Simultaneous to his work with Mary-Ann Wilson, Barack was conducting one-evening-a-week training for DCP members at Holy Rosary, while also drafting his own initial grant applications. The trainings, informed by what he had learned during his ten days with IAF, involved DCP veterans such as Dan Lee and Betty Garrett plus relative newcomers such as Aletha Strong Gibson. They also attracted new faces such as Loretta’s neighbor Margaret Bagby and Aletha’s close friend Ann West, a white Australian whose husband was black and president of the PTA at Turner-Drew Elementary School. Another important PTA figure, Isabella Waller, president of the regional Southwest Council, brought along her best friend, Deloris Burnam. Ernest Powell Jr., the politically savvy president of the Euclid Park neighborhood association and someone Barack had recruited over the summer, came as well. Close to twenty people attended the weekly sessions, at which Barack always took off his watch and put it on the table so he could see it during the training.

For Obama, the grant applications were a major concern. The first would go to Ken Rolling and Jean Rudd at the Woods Fund, which he hoped would renew the $30,000 given to CCRC for DCP in 1986. The ten-page, single-spaced document offered a retrospective account of the past fourteen months, and made clear, as he had stressed previously, that the Far South Side’s “two most pressing problems” were a “lack of jobs, and lack of educational opportunity.” Obama had one especially audacious goal for 1987: a “Career Education Network to serve the entire Far South Side area—a comprehensive and coordinated system of career guidance and counseling for high school age youth” with “a centralized counseling office” augmenting in-school counselors so as to reduce the dropout rate and channel more black high school graduates into higher education. “Youth in the area,” he warned, “are slipping behind their parents in educational achievement.”

Obama already knew that to build DCP two types of expansion were necessary: an outreach to congregations beyond the Roman Catholic base that Kellman had developed and the recruitment of more block club and PTA members like Eva Sturgies, Aletha Strong Gibson, Ann West, and Ernie Powell. DCP’s neighborhoods, from Altgeld northward to Roseland, West Pullman, and even solidly middle-class Washington Heights, were ill served by their elected officials, who “have generally poured their efforts into conventional political campaigns, with almost no concrete results for area residents.” Obama spoke of the need to “dramatize problems through the media and through direct action,” but DCP’s most pressing need was funds to hire another African American organizer. He realized a $10,000 entry-level salary would not attract experienced candidates, so DCP’s proposed 1987 budget called for $20,000 for that position and an increase in Barack’s salary to $25,000.

Ken and Jean at the Woods Fund told Barack to introduce himself to Anne Hallett, the new director of the small Wieboldt Foundation, whose interests closely paralleled those of Woods, and also to consider applying to the larger MacArthur Foundation. Obama visited and spoke with Hallett in November, and soon thereafter a front-page story in the Chicago Defender highlighted MacArthur’s announcement of $2.4 million in grants to community organizations, including $16,000 to Frank Lumpkin’s Save Our Jobs Committee. Before the year’s end, Obama submitted to Wieboldt a formal request for $10,000 that was virtually identical to the one he had sent Woods. Boasting that DCP was “an organization equal to any grass-roots effort going on in Chicago’s Black community right now,” Obama admitted that his employment and educational opportunities agenda represented “an ambitious program.” He said DCP needed “about two years” to recruit enough churches to be self-sustaining, and he told Hallett that DCP would soon reach out to MacArthur too.

The Far South Side’s two most notable developments in fall 1986 were both environmental. In late September, Waste Management Incorporated withdrew its long-pending application to open a new landfill west of South Torrence Avenue and would instead target the 140-acre O’Brien Locks site on the west bank of the Little Calumet River, surrounded on three sides by WMI’s huge CID landfill. UNO treated this news as a huge victory, infuriating environmental activists Hazel Johnson and Vi Czachorski, whose Altgeld Gardens and Hegewisch neighborhoods were just west and east of the O’Brien site. Johnson and Czachorski’s organizations, along with Marian Byrnes, formed a new antidumping alliance, Citizens United to Reclaim the Environment (CURE). Together with Sierra Club members, CURE organized a well-covered protest outside City Hall. As officials continued to seek the least bad solution to Chicago’s looming landfill crisis, UNO and CURE would be on opposite sides wherever the battle line was drawn. A few weeks later, 10th Ward alderman Ed Vrdolyak, a nemesis of Harold Washington as well as UNO, threw his support behind CURE.

That dispute seemed mild compared to a front-page headline in the October 25 Chicago Tribune: “South Side Facility Burning ‘Superwaste.’ ” The incinerator at 117th Street and Stony Island Avenue, little more than a mile from South Deering’s Bright Elementary School to the north and Altgeld Gardens to the southwest, was one of just five nationwide that was licensed to burn highly toxic PCBs. Although a front-page 1985 Wall Street Journal story ominously headlined “Plants That Incinerate Poisonous Wastes Run Into a Host of Problems” had cited the plant’s location, neither UNO nor most anyone else in Chicago had taken note that it was operating close to capacity, burning more than twenty thousand gallons of PCBs seven days a week. Experts agreed that incineration was much better than burial, but neither Illinois EPA nor Chicago officials had objected to this facility’s location.

In early November, United Neighborhood Organization held its annual dinner at an East Side banquet hall. Frank Lumpkin was one of two honorees, and the guest speaker was George Munoz, the new young president of the Chicago Board of Education. Newspaper photographs showed two of Chicago’s most promising Hispanic political stars—Munoz and Maria Elena Montes, as Lena’s name now sometimes appeared—seated on the dais. UNO and Gamaliel’s expansion had elevated Danny Solis to UNO’s executive director and Southeast Side organizer Phil Mullins to a supervisory role, and in Mullins’s stead, Bruce Orenstein, a young IAF veteran who knew Greg Galluzzo, took charge of UNO’s Southeast Side work.

As Barack was drawn into Greg Galluzzo’s UNO and Gamaliel network, one Gamaliel board member, John McKnight, stood out as the most intellectually intriguing voice at the regular gatherings, where most participants adopted a macho tone. Throughout the mid-1980s, McKnight had continued the same powerful themes he had voiced in earlier years. “Through the propagation of belief in authoritative expertise, professionals cut through the social fabric of community and sow clienthood where citizenship once grew,” he told one audience while warning of the danger that “a nation of clients” posed to a democratic state. In an article entitled “Community Organizing in the ’80s: Toward a Post-Alinsky Agenda,” McKnight and his younger colleague Jody Kretzmann declared that “a number of the classic Alinsky strategies and tactics are in need of critical revision.” Rather than confronting some “enemy,” the emphasis should be on “developing a neighborhood’s own capacities to do for itself what outsiders will or can no longer do.” The focus should shift public dollars away from salaries for service providers to investment in “local productive capacities” that will strengthen rather than weaken communities.

A year earlier, in November 1985, Chicago Magazine—a monthly not easily mistaken for a social policy journal—had devoted six glossy pages to a lengthy interview with McKnight. In the article, he said Chicagoans needed to recognize that “the industrial sector of America has abandoned us,” and that a new future loomed. “We’re turning out young people from universities right and left who really are looking for something to do. In the elite universities what do we offer them? We offer them the chance to become lawyers.” On the other hand, a sizable population of heavily dependent poor people was necessary to support the “glut” of professional servicers “who ride on their backs.” Public funds should be used to employ low-income people rather than pay servicers to patronize them. “To the degree that the War on Poverty attempted to provide services in lieu of power or income, it failed,” McKnight argued. “Poor people are poor in power.” For poor Chicagoans to become citizens rather than clients, “shifting income out of the service sector into economic opportunity for poor people is absolutely essential.”

In early 1986 McKnight wrote in the Tribune that instead of subsidizing medical behemoths, local health dollars should be directed toward “creating neighborhood jobs that provide decent incomes for local people.” In a subsequent interview, he decried “a society focused on building on people’s weaknesses,” one that emphasized “deficiency rather than capacity.” Service professionals’ control over the lives of the poor magnified rather than alleviated their poverty, for “if you are nothing but a client, you have the most degraded status our society will provide.”

Health services were the most dire problem, and publicly funded “medical insurance systematically misdirects public wealth from income to the poor to income to medical professionals.” Yet change would be difficult because “many institutional leaders” had come to see communities as nothing more than “collections of parochial, inexpert, uninformed, and biased people” who understood their own needs far less well than did service professionals. “Institutionalized systems grow at the expense of communities,” and America’s “essential problem is weak communities.”

John McKnight’s influence on people exposed to his social vision was profound even if unobtrusive. Ellen Schumer, a fellow Gamaliel board member and UNO veteran, said that within the world of Chicago organizing, McKnight “really challenged the old model.” His impact was also felt throughout Chicago’s progressive foundations, with Wieboldt acknowledging that it was “fortunate to have John McKnight join us” at the board’s annual retreat “to talk about the substantive changes in Chicago neighborhoods today that require new strategies for organizers.”

If McKnight was Chicago’s most significant social critic, the front pages of the December 3, 1986, editions of all three Chicago daily newspapers announced another: G. Alfred “Fred” Hess, a little-known policy analyst, education researcher, and former Methodist minister. After completing a Ph.D. in educational anthropology at Northwestern University in 1980, with a dissertation on a village development project in western India, Hess had joined the foundation-funded Chicago Panel on Public School Finances, and in 1983 he succeeded Anne Hallett as executive director.

Hess had made the front pages of Chicago’s daily papers nineteen months earlier thanks to a lengthy study entitled “Dropouts from the Chicago Public Schools: An Analysis of the Classes of 1982–1983–1984.” The Chicago Sun-Times had summarized Hess’s findings in a boldface banner headline: “School Dropout Rate Nearly 50 Percent!” His discovery that 43 percent of students who had entered Chicago high schools in September 1978 dropped out prior to graduation was a percentage that Obama had accurately cited a year earlier when he had written to Phil Boerner about the worst ills plaguing the neighborhoods where he worked. Hess’s data readily showed that high schools with predominantly minority populations had a dropout rate as high as 63 percent.

One Tribune story highlighted how at one Roseland high school, remaining in school did not mean students were studying. “We were sitting at a lunch table in the cafeteria rolling joints one morning,” a seventeen-year-old girl told reporter Jean Latz Griffin. “There was a security guard right next to us, but he didn’t say anything. People smoke it anywhere. Some teachers say ‘Put it out,’ but no one really does anything. You can’t snort coke inside school though. That would be too obvious.” Out of Corliss High School’s eighteen hundred students, only forty-eight were taking physics, only seventeen had qualified for the school’s first-ever calculus class, and almost 50 percent were enrolled in remedial English. A report similar to Hess’s, from a parallel research enterprise, Donald Moore’s Designs for Change, revealed that only three hundred out of the sixty-seven hundred students who had entered Chicago’s eighteen most disadvantaged high schools in 1980 had been able to read at a twelfth-grade level if they graduated in 1984.

In a prominent Tribune feature four weeks before Obama arrived in Chicago, Hess had warned that Chicago Public Schools (CPS) were damaging the city’s future. “We are in danger of creating a permanent underclass that is uneducated and unable to advance. It means a set of neighborhoods in which the majority of people are constantly unemployed and a strain on the social system in welfare and the high cost of crime. If we don’t take strong action now, we’ll pay for it later.” Don Moore emphasized how job losses were magnifying the consequences of CPS’s failures. “Parents are feeling a real desperation now because they are seeing unskilled jobs disappearing … 20 years ago the manufacturing industries in Chicago didn’t depend on employees being terribly literate. The economy has changed.” Former Illinois state education superintendent Michael Bakalis wondered to the Tribune why “the general community of Chicago, particularly the business community, has not been absolutely outraged by the performance of the Chicago Public Schools.” In July 1986, Hess told Crain’s Chicago Business that the way to reform public schools was to develop “real power for local citizens to control their local schools. Let local citizens hold local school officials accountable for the effectiveness of their schools. This would be real and significant decentralization of power that could make a difference.”

Illinois state law mandated that high school students receive at least three hundred minutes of daily instruction. Beginning in spring 1986, Hess’s Chicago Panel discovered that many Chicago high schools had fictional “study hall” classes in their students’ otherwise skimpy schedules that created a false paper trail to meet that requirement. The resulting report, “Where’s Room 185?,” released on December 2, created an immediate uproar. The Tribune editorialized that CPS “administrators are deliberately and illegally cheating students of part of the education to which they are entitled.” It also showed that in an overwhelming majority of actual classes, teachers actively taught for less than half of the class period. Noting how recently promoted CPS superintendent Manford Byrd’s response was to “hunker down and criticize the design of the study,” the Tribune declared that it was “inexcusable that it took an outside research panel” to uncover CPS’s “fundamental failure.”

The Chicago Defender ran a prominent page-three story, “Dropout Rate Irks Parents,” publicizing DCP’s desire to meet with board of education president George Munoz to discuss the problem. “We have a lot of dropouts,” DCP project director Barack Obama told the Defender. “We acknowledge that the dropout question is complicated, and there are no quick fixes to keep kids in school. We are urging Munoz to study the counseling system, recommend changes, and expand the numbers. This will have a direct effect on kids in the schools now.” Obama also said that students’ preparation prior to their high school years should be examined, “because there are a lot of possibilities out there.”

In addition, two public controversies highlighted Altgeld Gardens residents’ problems with both the CPS and the CHA. On December 4, one day after “Where’s Room 185?” debuted in Chicago newspapers, the Defender’s Chinta Strausberg reported on six teachers at the Wheatley Child-Parent Center who had transferred to other schools because they feared that Wheatley was permeated with asbestos. Superintendent Byrd insisted that tests had shown the air at Wheatley was “safe,” but Wheatley parents threatened to boycott the school and demanded an immediate inspection. On December 15 just 37 of Wheatley’s 377 young children attended school, and for the next two days that number dropped to 17 and then 11. One parent told the Tribune, “We can’t help but notice that the kids go to school all week and come home with rashes and wheezes. When they are home for the weekend, it all clears up.”

The boycott continued until the Christmas–New Year’s break, but being “home” at Altgeld was no picnic either, as a Tribune series detailing what it called the CHA’s “national reputation for mismanagement” documented. “If I had a job, I wouldn’t be here. This is not a good place to raise kids,” one young Altgeld mother told the newspaper while complaining about the prevalence of youth gangs. Two days later the Tribune reported that Zirl Smith was resigning as CHA executive director, and the next day’s paper emphasized how “Chicago has used the CHA as a way to isolate blacks.”

When news broke that administrative ineptitude had cost CHA $7 million in federal aid, CHA’s board chairman resigned as well. Fifteen months would pass before asbestos removal finally began in some 575 Altgeld homes, almost two years after Smith’s tumultuous visit to the Gardens. Harold Washington’s press secretary, Al Miller, later recounted the mayor remarking that “he didn’t believe there was a solution” to the CHA’s profound problems.

Shortly before Christmas, Barack Obama and Sheila Jager flew to San Francisco to spend a holiday week at her parents’ home in Santa Rosa. Although they had been living together for hardly four months, their relationship had quickly become one of deep commitment—indeed, so deep that for several weeks they had been discussing getting married during the trip to California.

Asif Agha had watched their relationship grow. Over the previous sixteen months, Asif had seen “Barry”—as he alone called Obama—acclimate to Chicago. “We were kind of an anchor point for each other,” and “Barry” spoke frankly to Asif about his acculturation. “I am the kind of well-spoken black man that white organization leaders love to give money to,” Asif remembered Obama remarking. Asif saw Obama with the eyes, and ears, of a linguistic anthropologist. “In terms of his performed demeanor, diction, speech style, he was white, not black,” Asif observed. Obama was open enough with Asif for him to know that Barack’s significant girlfriends prior to Sheila had been white, and Asif appreciated the underlying duality of Obama’s Chicago experience. His weekday work in Altgeld and Greater Roseland immersed him in African American life in a way that no prior experiences ever had, but in Hyde Park, his home life with Sheila and their occasional socializing with other anthropology graduate students was entirely multiethnic and international, just like his Punahou and Pakistani diaspora life had been in Honolulu, Eagle Rock, and New York.

Asif Agha. Eunhee Kim Yi. Arjun Guneratne. Their names alone, just like Sheila Miyoshi Jager, highlighted their international and ethnic diversity. Tania Forte was Egyptian, Jewish, and had grown up in France. Chin See Ming was born and raised in Malaysia before graduating with honors from Rice University in Houston. It was a “very, very cosmopolitan” group, Ming recalled, and when Sheila one day introduced Ming to Barack, I “just assumed he was a graduate student.”

For Sheila and her classmates, the first two years of the graduate anthropology program were “like boot camp,” Ming explained. Everyone had to take a double-credit introductory course called Sociocultural Systems, taught by Marshall Sahlins, a prominent anthropologist but “not a warm and cuddly person” and indeed “a very, very scary man” to some. Sheila coped far better with Sahlins than most of her classmates, and in her dissertation she wrote that “my greatest intellectual debt” was to Sahlins. “There was a very strong esprit de corps among the grad students” and “people worked very hard,” Ming recalled. “You were never off,” and everyone knew that student attrition would reach 50 percent.

Asif knew Sheila as “a very wonderful, wonderful person,” someone who was “passionate” about her work as well as her relationship with Barack. One evening the three of them accompanied Asif’s girlfriend Tammy Hamlish to a talk that her aunt Florence Hamlish Levinsohn, an outspoken local writer, was giving. Three years earlier Levinsohn had published a “patchy, parochial, frankly admiring” biography of her university classmate Harold Washington just after his election as mayor. Tammy had wanted Asif to meet Aunt Florence, but the evening quickly devolved into an unmitigated disaster. Asif remembered that he “started giggling at what the lady was saying, and Barry and I made eye contact, and that was fatal, because then for the next ten minutes we kept uncontrollably giggling and couldn’t control it and almost falling off our chairs because what the lady was saying was just absurd. And neither of us could control it, and because we were sitting next to each other and kept making eye contact, we’re triggering each other over and over and over. Tammy meanwhile is turning red,” and Levinsohn took note of their behavior too. She “was most upset” and “Tammy was mortified,” Asif recalled.

Apart from that embarrassing scene, Barack and Sheila were familiar faces at anthropology graduate students’ occasional parties. Sheila Quinlan, a Reed College graduate who was a year ahead of Sheila, remembered how “everyone thought they were a very sincere couple.” Barack was “quiet,” “friendly,” and “a sweet boy.” Indeed, as Chin See Ming put it, Barack “fit into the scene,” just as he likewise had learned to do in Roseland and even down in the Gardens. Jerry Kellman watched as Obama comfortably embraced his dual lives. “He found a way to be part of the black community and live beyond the black community,” Kellman explained. “He discovered he could live in both worlds.”

But in December 1986, and for almost two years thereafter, the looming and overarching question was whether Barack Obama could live in both worlds with Sheila Miyoshi Jager as his wife. Five months earlier, before asking Sheila to live with him, he had inquisitively questioned Arnie Graf about the long-term dynamics of interracial marriage and raising half-black, half-white children. And although most passersby and even most anthropology students would not see them in such a way, Sheila knew that “Barack is as much white as I am.” With her half-Japanese ancestry paralleling his half-Kenyan, she and Barack were equally white—one half apiece.

“Marriage was THE vital issue between us and we talked about it all the time,” Sheila explained more than two decades later. Barack “kept work matters and his private life separate,” so their marriage conversations, while known to Asif, were not something Kellman, Kruglik, Tom Kaminski, or Cathy Askew ever heard about from someone so “very private” as Obama. In their time alone together, Sheila saw someone whom no one in DCP ever did, someone with a “deep seated need to be loved and admired.” In their evenings at the spacious apartment on South Harper, Barack read literature, not history, while Sheila had more than enough course readings to occupy her time. And, of course, there was another dimension as well. Barack “is a very sexual/sensual person, and sex was a big part of our relationship,” Sheila later acknowledged.

Everything had come together fast. In “the winter of ’86, when we visited my parents, he asked me to marry him,” Sheila recounted. Mike Dees, her father’s closest friend and Sheila’s virtual uncle, had been told by Bernd in advance that Barack was a prospective son-in-law. “He and Sheila … were going to get married,” Dees explained. “They were coming out, they wanted to get married, and so they called me to come up and look the guy over and see what I think.”

One day right after Christmas Mike drove up to Santa Rosa, and “I ended up with Barack for an afternoon,” he recalled. “We just visited.” Barack was clearly a “very bright guy,” and, complexion aside, came across like “a white, middle-class kid.” Then, after dinner, Bernd and Mike had “a big political thing with Barack” while Sheila and her mother Shinko were occupied elsewhere. The two older men and Barack found themselves on “completely opposite sides of the fence,” Mike explained, because “we’re both conservative Republicans.” Barack “kind of thought he was going to lecture to us” about politics and ideology, “and we kind of shot him down.” It got “really heated” and “went on for quite a while.” Barack seemed “very taken aback by it,” Mike recalled. “Barack kind of thought he was going to sit down and get anointed. He’s very self-centered, and he ended up getting beat up.”

Although Barack “didn’t do very well,” to Mike “it was just a political argument. I think to the father and Barack it was more than that,” indeed, much more. “For Barack it was a big deal, for Bernd it was a big deal,” because Barack “was going to be the chosen one that night, and it didn’t work out” that way. It was readily apparent that the older man was sitting in judgment on the younger, perhaps not so differently from the time twenty-five years earlier when Stan Dunham had first met Barack Obama Sr. But here the verdict was negative, not positive. “I don’t know whether his color entered into the picture or not,” Dees said about Bernd’s attitude toward Barack.

By the end of the evening, and again the next morning, Bernd made his view of Barack and his marriage proposal crystal clear. “Bernd was against it,” because he felt that Barack was unworthy of his daughter’s hand. Sheila remembers that “my father was concerned over his ‘lack of prospects’ and wondered whether, as a community organizer, he could even support me, something that deeply offended Barack. My mom liked Barack a lot, but simply said I was too young” to get married. “I went along with their judgment, basically saying ‘Not yet,’ ” she recalled. The unsettling holiday visit concluded, and “they ended up going back without getting married,” Mike Dees affirmed.

Barack and Sheila would revisit that decision again and again over the twenty months that lay ahead.