По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

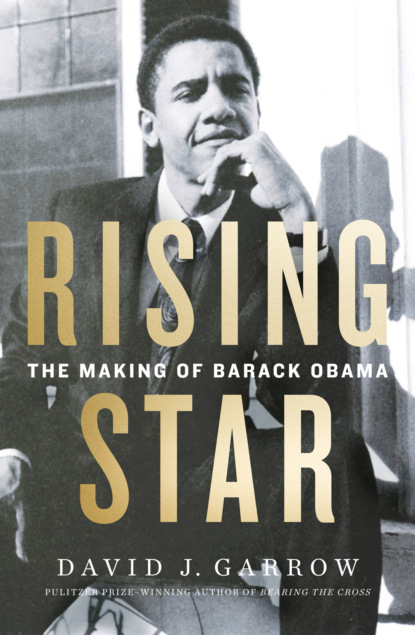

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Ever since early summer, Obama had met ambivalence among DCP’s congregations about forcefully targeting the sorry state of Chicago’s public schools. He later acknowledged that “every one of our churches was filled with teachers, principals, and district superintendents,” or, as UNO’s Phil Mullins more pungently yet properly put it, “if you removed every education bureaucrat from Reverend Wright’s church, it would go under.” Barack spent much of the last months of 1987 trying to expand DCP’s base by approaching the pastors of largely Protestant, and mainly Baptist, Greater Roseland churches. He realized that these congregations “have had no direct involvement in the issues surrounding the public school system,” and DCP wanted to enlighten them about “the need for broader reform in the school system.” Jerry Kellman knew that Mary Bernstein’s father, a senior Teamsters official, was a close colleague of Robert Healey, a former Chicago Teachers Union president who was now head of both the Chicago Federation of Labor and the Illinois Federation of Teachers. Mary arranged for Obama to meet with Healey, but Healey had no interest in aiding a movement that would empower parents.

Roseland’s five high schools were in sorry shape. One study revealed, “High school students in Roseland are testing more than ten percent below the city-wide average,” and that average was more than 30 percent below grade-level norms. The dropout rates at the two weakest schools, Harlan and Corliss, were rapidly increasing. Corliss’s principal published an essay in the Journal of Negro Education describing her efforts to combat “gang activity and vandalism,” “low teacher morale,” “disrespectful attitude and behavior of students,” and “student apathy and high failure rate” at her school. Julian, named after the pioneering black chemist Percy Julian, was considered to be the best of the five, but the principal there, Edward H. Oliver, still had a serious problem with ganglike female “social clubs.”

A crowd of three hundred showed up for CEN’s November 17 kickoff rally at Tyrone Partee’s Reformation Lutheran Church. The Defender covered the event, where DCP announced it would begin offering tutorial and counseling services at both Holy Rosary and Reformation in early 1988 to students referred by Carver, Fenger, and Julian high schools. Olive-Harvey College president Homer Franklin as well as Chicago State University vice president Johnny Hill pledged their institutions’ assistance, and Chicago United policy director Patrick Keleher said that his organization would arrange for employment internships.

Barack was also keeping up with the city’s landfill crisis. When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a report attributing the South Side’s poor air quality to highway traffic and wood-burning stoves without mentioning landfills, the Tribune said that UNO’s Mary Ellen Montes “laughed when told of the EPA’s findings. ‘That’s crazy. Wood-burning stoves? Are there any left?’ ” Then the Sun-Times revealed that the Paxton Landfill had been operating without the necessary permits since 1983. The newspapers had a field day at the Washington administration’s expense, but mayoral aide Howard Stanback remained focused on the O’Brien Locks issue.

On November 16 South Chicago Savings Bank president Jim Fitch convened an initial meeting of all interested parties, ranging from South Deering’s Foster Milhouse to Bruce Orenstein and Mary Ellen Montes from UNO and hard-core landfill opponents Marian Byrnes and Hazel Johnson, who did not like anything they heard. Four days later Lake Calumet environmentalist James Landing distributed a letter warning that the Washington administration “is making prodigious attempts” to win over opponents of a new O’Brien Locks landfill.

On Wednesday morning November 25, the day before Thanksgiving, a Chicago Tribune headline announced “948 School Jobs Axed for Teachers’ Raises.” In order to meet the pay raises in CPS’s new union contracts, 167 elementary school teachers had been terminated. Then, at 11:01 that morning, Harold Washington collapsed with a heart attack in his City Hall office. The sixty-five-year-old mayor was seriously overweight, and attempts to revive him were unsuccessful. An official announcement was delayed for more than two hours, but word that Washington had died spread rapidly throughout the city, with tearful crowds gathering outside City Hall.

“Mayor’s Death Stuns City” read one headline the next day. Black Chicago’s loss was especially painful and heartfelt. Seven months earlier, when Washington was reelected, the Tribune editorialized that “he has been a symbol more than a leader,” but he was also the greatest “symbol of black empowerment” the city had ever seen. Only with his April 1986 erasure of Ed Vrdolyak’s city council majority had Washington truly become Chicago’s mayor, and as one Tribune story poignantly declared, “Washington’s legacy is not what he did, but what he was on the verge of doing.”

The next morning the Tribune lauded Washington as “a symbol of success and dreams realized for people who felt they had little reason to dream, let alone achieve,” while again noting that “his tangible record of accomplishments is a short list.” Economic development commissioner Rob Mier would write that “many of his goals and plans remained unfulfilled or barely started.” Mier also recognized that Chicago’s loss was greater because Washington had “died at the peak of his power.”

Tribune reporter John Kass highlighted how Washington had been “an incredibly charismatic leader,” but one of Washington’s most fervent early backers identified the mayor’s greatest mistake. “He took the power to himself, almost like Mayor Daley” in earlier decades, “and the political maturity of black politics stopped while he increased his power.” White 49th Ward reform alderman David Orr, who became interim mayor upon Washington’s death, had articulated the underlying problem months earlier: “There’s a large group of black aldermen … who don’t support reform but who have to vote with the mayor because he’s so popular in their wards.” By tolerating rather than purging those black aldermen who professed to support him while nonetheless remaining fully loyal to the Democratic party machine, Washington had advanced “his own political self-interest at the expense of institutionalizing his reform movement,” wrote historian Bill Grimshaw, the husband of Washington’s top political aide, Jacky Grimshaw.

The enormity of Washington’s failure became clear within the first hours after his death, as his city council majority sundered into two angrily hostile camps. Washington’s true supporters rallied behind the mayor’s council leader, 4th Ward alderman Tim Evans, with whom Barack and DCP’s Altgeld asbestos protesters had met eighteen months earlier. Washington’s opponents eagerly reached out to the black machine aldermen, who now controlled the balance of power in a political world where they no longer had to bow to a singularly charismatic leader. Washington’s political base “unraveled immediately after he was pronounced dead,” John Kass wrote, and Rob Mier also rued “the immediate collapse of his political coalition.”

Over the Thanksgiving holiday weekend, the two factions warred publicly as Washington’s body lay in state for a fifty-six-hour around-the-clock wake in the lobby of City Hall. Monday night at the UICC Pavilion where Washington had hosted his Education Summit just seven weeks earlier, his official memorial service turned into a political rally for Evans. Yet the only votes that would count were those of the fifty city council members, and by Tuesday morning, there was little question that 6th Ward black machine alderman Eugene Sawyer would become Chicago’s next mayor thanks to Washington’s hard-core opponents plus at least five black aldermen who would support Sawyer over Evans.

As Tuesday night’s council meeting convened, a crowd of thousands stood outside City Hall, chanting “No deals” and “We want Evans.” Clownish behavior marred the council’s proceedings as protesters mocked black Sawyer allies like 9th Ward alderman Robert Shaw, and Sawyer was not formally elected as Harold Washington’s successor and sworn into office until 4:00 A.M. Wednesday.

In skin color Gene Sawyer was just as black as Harold Washington, but as the angry crowd well knew, Chicago now had a completely different mayor than the one it had just buried. When Sawyer was asked by a historian some months later about Washington nemesis Ed Vrdolyak, his answer highlighted the chasm: “He’s a fun guy!”

“I loved Harold Washington,” Barack blurted out years later when asked what he had thought of the mayor. He once wrongly but perhaps wishfully stated that in 1985 “I came because of Harold Washington,” and at another time, he mused that “part of the reason, I think, I had been attracted to Chicago was reading about Harold Washington.” There was no doubt that Washington, or more precisely Washington’s treatment at the hands of the Vrdolyak majority during Barack’s first nine months in Chicago, contributed in some degree to Barack’s own embrace of a resolutely black racial identity. “Every single day it was about race. I mean every day it was black folks and white folks going at each other. Every day, in the newspapers, on TV, in meetings. You couldn’t get away from it,” Obama later recounted. “It was impossible for Harold to do anything.”

Upon his arrival in Chicago, and throughout all of his Oxy and Columbia years prior to Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential run, Barack had been “skeptical of electoral politics as a strategy for social change,” he later acknowledged. “I was pretty skeptical about politics. I always thought that the compromises involved in politics probably didn’t suit me.” Jerry Kellman, Greg Galluzzo, and the Alinsky tradition of organizing certainly did not teach respect or admiration for elected officials. But watching Washington week after week, even if he had never been physically closer than in that nondescript Roseland storefront eight months earlier, had fundamentally changed Barack’s mind. “You just had this sense that his ability to move people and set an agenda was always going to be superior to anything I could organize at a local level,” Obama explained in 2011.

In his own telling years later, Obama was in that angry, chanting crowd outside the city council chambers that Tuesday night, witnessing what he called Washington’s “second death.” Yet even at the time he wrote that, Barack understood Washington’s fundamental error, just as Bill Grimshaw had explained it. “Washington was the best of the classic politicians,” Obama told an interviewer. “But he, like all politicians, was primarily interested in maintaining his power and working the levers of power. He was a classic charismatic leader, and when he died, all of that dissipated. This potentially powerful collective spirit that went into supporting him was never translated into clear principles, or into an articulable agenda for community change,” Obama rightly stated in words that would echo painfully two decades later. “All that power dissipated.”

Yet in those last weeks of 1987, Washington’s death strengthened Barack’s belief that now was the time to leave DCP for law school. He had “a sense that the city was going to be going through a transition, that the kinds of organizing work that I was doing wasn’t going to be the focal point of people’s attention because there were all these transitions and struggles and tumult that was going on in the African American community,” he recalled in 2001. “So I decided it was a good time for me to pull back” and attend law school.

Barack’s long-pondered personal essay was finished, but completing his application required soliciting letters of recommendation as well. Al Raby was a recognizable name to anyone who knew the history of the 1960s, and Michael Baron had given him an A for his senior year paper at Columbia, the most serious piece of coursework Barack had ever tackled. Now working at SONY, Baron readily agreed to write a letter. But Baron’s knowledge of him was now more than four years dated, so Barack also went to see John McKnight, asking him to keep their conversation confidential, especially from Greg and Mary. “Would you write me a letter of reference? You’re the only professor I know.” McKnight immediately said yes, but asked Barack what his plans were. “I want to go into public life. I think I can see what can be done at the neighborhood level, but it’s not enough change for me. I want to see what would happen in public life” and “I think I have to go to law school to do that.” McKnight questioned whether Barack understood how fundamentally different life as an elected official would be from that of an organizer. While the latter was quintessentially an advocate, “my experience is that legislators are compromisers,” McKnight observed, people who synthesize conflicting interests. “You want to go into a world of compromise?” he asked. Barack responded affirmatively, saying, “That’s why I want to go into public life” and to pursue a role quite opposite that of a confrontational Alinsky organizer. “It’s clear to him he’s making a decision that that’s not the way he’s going,” McKnight remembered. “He left for a different mode of seeking change.”

With Gene Sawyer uncomfortably ensconced in City Hall, the Parent Community Council’s ten public forums were surrounded by uncertainty. At the first one, Chicago United’s Patrick Keleher reiterated the business community’s demand for dramatic reforms, and at the third Sawyer pledged “my commitment to the Washington reform agenda.” In response, Manford Byrd protested that CPS’s “many needy students” meant that any improvement in schools’ performance would require “major additional funding” for more teachers, counselors, and, of course, “other professionals.” DCP’s Aletha Strong Gibson told one reporter that the reform movement would be undeterred by the mayor’s loss. “Harold Washington did not move the community. The community moved Harold Washington,” she declared. “It is incumbent upon us to keep our voices raised. We have to take back ownership of the schools.”

Sawyer also inherited Chicago’s landfill problem, with Howard Stanback seeking to quickly explain the city’s O’Brien Locks strategy to the new mayor. Environmental activist James Landing realized that Washington’s death would not alter the situation, and even he wondered whether the opponents should give up and join Jim Fitch’s effort to agree on what the Southeast Side neighborhoods should demand from WMI. Senator Emil Jones’s special legislative committee concluded its investigation by ruing “the lack of one centralized authority to address all environmental problems” in the area, but also bluntly acknowledging that continuing Chicago’s ban on landfill expansion “is irresponsible unless the city is able to implement a successful citywide waste-disposal plan” through massive recycling.

At DCP, Barack and Johnnie were preparing the CEN tutoring program to start in early 1988, in both Roseland and Altgeld, undeterred by the December murder of an eighteen-year-old Gardens youth by five fellow teenagers, all members of the infamous Vice Lords gang. Weeks earlier Barack had asked Sheila to go with him to Honolulu for the Christmas holidays so that his relatives could meet her, the first time Barack had ever introduced a girlfriend to his family.

Madelyn had just turned sixty-five, and a year earlier had retired from the Bank of Hawaii. Stanley, almost seventy, was now retired too. Ann Dunham, still struggling to complete her dissertation, told her mentor Alice Dewey how much she was looking forward to meeting Sheila, and Sheila would always remember how exceptionally warm Ann was to her throughout the couple’s visit to Honolulu. Ann was fascinated that Sheila had written her master’s thesis on Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Sheila remembers the two of them “talking about that thesis, my time in Paris, and my work at Chicago.” Ann was “genuinely very interested and warm and inquisitive. She was extremely generous with us and treated Barack with reverence. She really admired him and thought the world of him.”

Even though Ann and Sheila liked each other very much, Sheila felt that Ann was not in favor of her and Barack getting married. She wondered if Ann “sensed what we already knew, that we were too isolated and would sophisticate each other.” Sheila was especially struck by how everyone in Hawaii—Gramps, Toot, Maya—called Barack either “Bar” or “Barry.” In Chicago, only Asif used “Barry.” When Sheila called him “Barry for fun one day, just because everyone else was calling him that name,” Obama’s reaction was unforgettable. “He got so angry at me. Irrationally furious, I’d say. He told me that under no circumstances was I ever to use that name with him.” Perhaps Obama had some deep boy-versus-man association to the two names, but Sheila understood that he “was very sensitive about this aspect of his life and wanted me walled off from it—like a lot of other things in his life.”

Back in Chicago, the mayor’s Parent Community Council moved toward recommending that each Chicago public school be controlled by a locally elected governing board, but without Harold Washington present to embrace its conclusions, school reformers started arguing over which of several just slightly different proposals should be introduced in the state legislature. DCP participated tangentially, following UNO’s lead, with Danny Solis in charge and Johnnie Owens rather than Barack following developments most closely.

In late January Barack wrote to Phil and Karen Boerner to apologize for missing their wedding, and updated them on his plans: “I’ve decided to go back to law school this fall—probably Harvard.” At the end of the month, Barack also wrote to Anne Hallett at Wieboldt to submit DCP’s 1988 grant application, but he gave no indication that he might be leaving DCP anytime soon. He wrote that “DCP has come a long way in the past year,” most notably in hiring Owens, “someone with both the talent and background to become a lead organizer in his own right.” Because of DCP’s “success with the education issue … we have the potential in the coming year to become a truly powerful advocate for change not only in the area, but citywide,” Barack boastfully asserted. “Whether we fulfill that potential will depend on two things: how well we parley the Career Education Network into a vehicle for organizing parents and community, and whether the relationships we have established with the major Black churches in the South Side translate into their making a full commitment” to DCP by contributing financially so that the organization could begin to wean itself from outside funders. “If we succeed, I envision us having 30 new churches involved by the end of 1988.”

That was optimistic, because Obama’s ongoing efforts to connect with dozens of black pastors had garnered polite conversations but few enlistments. If CEN was to grow beyond a small pilot program in which DCP housewives tutored dozens of high school students in a trio of church halls, funding was necessary for “significant expansion of the program by the State Legislature.” Barack also still hoped that Olive-Harvey could reallocate resources “to create a comprehensive job training program with specific emphasis on Public Aid recipients and with the outreach and satellite facilities necessary to target the Altgeld Gardens population.”

DCP would soon hire a CEN project coordinator, thanks to Emil Jones’s state money and the Woods Fund, and hoped to approach major corporations through Chicago United. Barack’s success at fund-raising had let him raise his own salary to $27,250 and Johnnie’s to $24,000. Ideally Olive-Harvey would foot the bill to house CEN, but expanding the program for the 1988–89 school year depended on state board of education officials and state legislators.

Obama believed that “parents and churches” were “the most crucial ingredients” for “a long-term process of educational reform.” Gamaliel and Don Moore’s Designs for Change, now a top player in the citywide school reform movement, could be asked to provide parental training. The city’s community colleges were responsible for vocational and general educational development (GED) training, but their actual track record was even worse than that of Chicago Public Schools. “Only 8 percent of the 19,200 persons enrolled in GED preparation classes in 1980 actually received certificates,” Barack had discovered, and “only 2.5 percent of those enrolled in City College basic education programs end up pursuing additional vocational or higher education.” Instead, just as at CPS, “funds go into central administrative tasks rather than student instruction.”

Barack’s church-recruitment efforts continued throughout the winter of 1987–88. One successful visit was to a small church on West 113th Street just across from Fenger High School. Thirty-two-year-old Rev. Alvin Love had arrived at Lilydale First Baptist Church four years earlier, inheriting an “elderly congregation” that was “comfortable sitting and doing nothing.” Love wanted to “get this congregation engaged in their community,” and he was happy when Obama “just walked up to the door and rang the bell” and asked if Love would tell him what he thought Roseland needed. Love, like other pastors before him, asked Barack which church he belonged to. Love warned Barack that his standard response—“I’m working on it”—wasn’t going to be acceptable to all black clergymen. Barack invited Love to a box-lunch gathering of other interested pastors, and he was slowly beginning to expand DCP’s ties to freestanding Protestant congregations.

The clergymen with whom Barack was having the most contact, however, were not involved at all in DCP. One was Jeremiah Wright at Trinity United Church of Christ, whom Barack continued to visit on a regular basis. Barack also began speaking with Sokoni Karanja, a longtime Trinity member whom he had met through Al Raby when Karanja emerged as one of the most outspoken African American voices calling for school reform. Barack “was trying to think about ministers and how to organize ministers across the whole city—African American ministers—because he felt like the power that was needed for the community to get its just due was through that,” Sokoni remembered. “He was trying to think about churches and how to organize the churches.” Barack also told Sokoni about his plan to attend law school. “One of the things I notice is that a lot of these politicians get in trouble because they don’t know the law,” Barack commented. Becoming a politician was indeed his goal. “He was talking about becoming mayor of Chicago,” Sokoni—just like Mike Kruglik—remembered. “We had a lot of conversations about it,” and “that’s what he emphasized to me. It sounded like a good idea.”

The other church Barack visited frequently was St. Sabina. DCP members like Cathy Askew, Nadyne Griffin, and Rosa Thomas knew Barack “was a big admirer of Father Pfleger,” but Cathy’s fellow St. Catherine’s parishioner, Deacon Tommy West, saw the most of Barack at St. Sabina. One of St. Sabina’s wintertime ministries involved a tangible outreach to the homeless, many of whom lived in the relative warmth of Lower Wacker Drive, the underground level of a downtown Chicago roadway. “We brought clothes and food down there for them,” West explained. “My wife made corn bread” and “minestrone soup.” One evening Barack joined Tommy and Mike Pfleger for the trip downtown. “He was with us underground, feeding the homeless,” West recounted. “Lower Wacker—I remember him going to that with us,” Mike agreed. Tommy also remembered Barack saying he was about to go back to school. He “told me when he went down to Wacker Drive with us and we had the soup and the coats.” Tommy had asked why, and he recalls Barack saying, “I just get tired of getting cut off at the pass” by government officials, and “I need some other stuff. I’ve got to go. This is something I have to do.”

But one day in those early months of 1988, Barack went with Mike Pfleger and Tommy West on a different sort of outing. Years later Barack would say that “the single most important thing in terms of establishing” safe neighborhoods “is having a community of parents, men, church leaders who are committed to being present and getting into the community and making sure that the gangbangers aren’t taking over, making sure that there’s zero tolerance for drug dealing.” In 1988 Pfleger shared that sentiment as strongly as anyone could, and he had adopted an interdiction technique that was nonviolent direct action at its most aggressive: walking into a known drug seller’s home in clerical garb, asking if he could use the bathroom, then grabbing whatever narcotics he could and heading for the toilet. Only “a very small group” of men accompanied Mike on such drug raids, and Tommy West—wearing a deacon’s collar—was a regular participant.

Pfleger cannot remember Barack going with him on such a sortie, although “he very well may have.” But Tommy West recalls Barack’s involvement with great clarity. “One time he went with us to this drug dealer’s house, and Father Mike grabbed up the guy’s drugs and ran in the washroom—first he asked the guy, could he use the washroom,” and once in there Mike “dropped it and flushed it, and the guy pulls out his pistol. I said, ‘Look, put that up. He’s a priest—you don’t want to hurt him. Use it on me.’ He said, ‘No, he’s the one who did this.’ I said, ‘Don’t touch him. That’s God’s man. You don’t want God to be down on you the rest of your life. Leave him be and try to find you somewhere else.’ He said, ‘I think I will, because I’m ready to kill him.’ So Barack said, ‘Woo.’ ” Mike Pfleger looked calmly at his colleagues. “I’m doing God’s work. God is taking care of me.”

“He was around for that one,” Tommy affirmed. “That was the first time I remember him going inside of the drug dealer’s home with us to see what Father Mike did.” Then, with the dealer still holding his gun, Tommy again asked the man to leave: “ ‘then we can get out of here.’ ” The dealer did take his gun and leave, and as the raiding party exited as well, “everybody was kind of shook up,” Tommy West recalls with considerable understatement.

Barack had developed significant relationships with Mike Pfleger and Jeremiah Wright, just as he had two years earlier with Bill Stenzel and Tom Kaminski. But at home on South Harper, Sheila Jager never heard a single word about any of them, or about institution-based religious faith. “I don’t think Barack ever attended church once while we were together,” and he “certainly was not religious in the conventional sense,” Sheila reiterated. Barack “never suggested going to church together,” and “I had no awareness of Jeremiah. He certainly never mentioned him to me.”

Barack’s closest Hyde Park male friend, Asif Agha, remembers their conversations similarly. “I always assumed he was an atheist like me.” Barack “had no interest in religion” and knew “nothing about Islam.” Asif’s friend Doug Glick, Barack’s companion on all those long summer drives to and from Madison, bluntly concurred. “I do not believe he believes in Jesus Christ.” Asif states the trio’s consensus succinctly: Barack “did not have a religious bone in his body.”

In Barack’s daily life with Sheila, “he didn’t tell me a whole lot about” who he was dealing with in his work, Sheila explains, “although he did bring a lot of their ideas home.” Barack “never compartmentalized ideas, which we discussed freely.” At home “we spent a great deal of our time discussing/talking about all sorts of things, which was one of the things I liked so much about him.” And, just like at DCP, Barack “was also a very good listener.” Yet “we lived a very isolated existence,” and even their immediate neighbors at 5429 South Harper barely remember either Barack or Sheila.

One longtime older resident had no recollection at all, and custodian Joe Vukojevic, who lived directly across the hall from Barack and Sheila, only remembered being introduced to Barack’s mother Ann during her summer 1987 visit. Barack and Sheila’s immediate upstairs neighbors, John Morillo and Andrea Atkins, thought Joe the janitor was “a very nice guy” but “practically never” saw Sheila or Barack. They would remember the unusual name on the mailbox, and saying hi to Sheila, but Barack was “just another guy doing laundry” in the basement laundry room.

On January 31, the Daily Calumet reported that South Chicago Savings Bank president Jim Fitch was privately brokering talks to allow Waste Management to use the O’Brien Locks site as a new landfill in exchange for a $20 million community trust fund. Fitch then called for another gathering of neighborhood representatives at 7:30 P.M. Monday, February 8, at his bank to discuss “the structure of the community trust.” Since the Daily Cal story “events have been evolving rapidly,” Fitch explained, and “conversations with Waste Management have continued.”

UNO’s Bruce Orenstein and Mary Ellen Montes had previously attended Fitch’s conclaves, but now they grew concerned. If UNO and the city’s Howard Stanback hoped to have the community fund managed by mayoral allies, they could not allow Fitch to continue driving the conversation with WMI. Bruce and Lena called on Fitch at his bank in advance of the meeting and told him he lacked the authority to have this gathering because he had not been involved in the fight to stop the landfills. Bruce recounts telling him, “We think you’re undermining our agenda, you’re undermining the agenda of the community, the wishes of the community.” Bruce and Lena “really asked him to stop,” but Fitch was no rookie at power politics. He recognized their raw grab for control and brusquely dismissed them.

Orenstein next called Barack to ask for DCP’s support in a confrontational move straight out of the Alinsky-style community organizing playbook. Local print and broadcast journalists were notified, a press release was prepared, and late Monday afternoon prior to the scheduled meeting, Barack, Loretta Augustine, and other DCP members drove to UNO’s office on East 91st Street, less than two blocks from Fitch’s South Chicago Savings Bank. “We met there, we practiced,” Bruce remembered. “Barack and I and Mary Ellen and Loretta have devised this thing,” and shortly after 7:30 P.M., Mary Ellen led a column of more than one hundred participants, including some children, out the door and down the street toward the bank’s second-floor conference room. The goal was “to let Fitch know in no uncertain terms he does not represent the will of the community on this issue,” Bruce recounted. “We just wanted to tell him that in front of everybody else who was around the table,” including UNO and DCP’s old friend Bob Klonowski, pastor of Hegewisch’s Lebanon Lutheran Church. Bruce remembered the group very quietly “walking up the stairs and being actually quite nervous,” for “it was quite a confrontational approach to things.”

But with Mary Ellen in the lead, the “ambush”—as the Daily Cal’s front-page headline the next day called it—worked to perfection. “Mary Ellen led the charge and we walked in and the camera lights went on,” Bruce recalled. “Barack and Loretta and the TV cameras and the Chicago Tribune” reporter Casey Bukro all followed Lena into the conference room. “Everybody looks up” as Mary Ellen approached Fitch. “Tonight we publicly take the position ‘No deals Jim Fitch, no deals Waste Management,’ ” Lena proclaimed. “We will fight you every step of the way.” As a confrontational leader, “she was fantastic,” Bruce knew. “Then we turned on our heels and walked out.” It was a “very memorable action,” even “a hoot of an action,” and from Bruce’s perspective, Barack had shown no discomfort with these tactics: “I certainly think he enjoyed it.”

UNO and DCP’s press release claimed that “We are diametrically opposed to any ‘buyoff’ deal … with Waste Management,” while acknowledging that “communities are due substantial reinvestment.” A simultaneous one by Howard Stanback on behalf of the mayor’s office was deceptively titled “City Reaffirms Landfill Moratorium” and asserted that “Waste Management is misleading the public if they suggest that they are in a position to acquire O’Brien Locks for landfilling.”

As Bruce Orenstein told the Daily Calumet, “If Waste Management gets ahold of that property, out the window goes any protection for the community.” The real issue was not the fate of the O’Brien Locks acreage, whose future looked preordained, but who on the Southeast Side would control whatever community trust fund would receive the $20 or $25 million that Waste Management was clearly willing to pay. Only Hegewisch News editor and community activist Vi Czachorski gave readers a clear understanding of what was happening. “Montes wants a landfill at the O’Brien Locks,” directly across the Calumet River from Hegewisch, and in exchange, she gets “a trust that UNO would operate” rather than Jim Fitch and other traditional Vrdolyak loyalists. But UNO’s Alinskyite “ambush” not only infuriated Fitch’s nascent coalition, it also angered the trio of hardcore landfill opponents—Jim Landing, Marian Byrnes, and Hazel Johnson—who had been reconsidering their own position. Within a week, they were picketing outside Chicago’s City Hall, clear evidence that Bruce and Barack’s strategy of blowing up Fitch’s negotiations had torpedoed any prospect of achieving a community-wide consensus.

For Barack, all this tussling created a fundamental personal tension. He had made clear to John McKnight that he rejected the confrontational politics of the Alinsky tradition, even though he had just helped lead an action that was so pugnacious it had made even the hard-bitten Orenstein nervous. It unquestionably was the “most confrontive meeting he had ever been involved in,” Bruce acknowledged, and “left to his own devices, I don’t think he would have designed an action like that.” True enough. What then accounted for so stark a contradiction?

A weekend or two after the South Chicago ambush, Barack took Sheila to see a movie that had debuted the Friday before the Fitch action: The Unbearable Lightness of Being, an adaptation of Czech writer Milan Kundera’s 1984 novel. Set in Czechoslovakia in the years leading up to the Prague Spring of 1968, the film featured three leading characters: Tomas, a young doctor, his partner Tereza, and his additional lover Sabina. The movie was not necessarily loyal to the spirit of Kundera’s book, and, at almost three hours’ length, it had not been praised in prominent reviews in the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times. The Tribune’s critic wrote that “the film has no vision and no life,” and warned that it “is likely to be incomprehensible to anyone who hasn’t read the novel.”

Vincent Canby’s Times review was more revealing. Tomas, played by Daniel Day-Lewis, lived a compartmentalized life, with “one part of his mind” analyzing something while another “part that’s outside it criticizes” the first. Tereza, played by Juliette Binoche, “falls profoundly in love with” Tomas “without knowing anything about him.” In turn, “Tomas is drawn against his will into commitment to Tereza,” yet with Sabina, played by Lena Olin, he indulges in “a passion for … sex that excludes serious emotional commitment … while always remaining a little detached.” Tomas “remains committed to Tereza, though still unfaithful.” The film conveyed “an accumulating heaviness” accentuated by its “immense length.”

Almost a quarter century later, Sheila Jager described the film as an indelible memory, explaining that it could offer “some insight into our relationship…. Although Barack did not fool around (not that I know of), I remember being powerfully moved by that film when we saw it together because Tomas and Tereza’s relationship seemed to so uncannily mirror the dynamics of our own—Tomas’s ‘neurosis’ like Barack’s ‘calling.’ ” She believed that perhaps was “why I reacted so hard when I saw that film. Because it was mirroring reality in an eerie sort of way, and I somehow understood what was happening even if I was unaware of what was going on. I remember feeling so trapped and suffocated back then, just like poor Tereza and her cheating husband. I’ll never forget that feeling of desperation, and wondering what I was going to do. I remember him telling me how he wished he could take me to the countryside and live with me,” just as Tomas does with Tereza, “but he couldn’t do that, no matter how much he loved me,” because his destiny inescapably must trump love. “I always knew that I couldn’t marry him,” yet in those early months of 1988, Sheila never doubted Barack, in part because something happened between them, something Barack subsequently never spoke about.

Barack was also close with the almost thirty-year-old Mary Ellen Montes—Lena—and he told her too about the vision of his future that otherwise he had only shared with Sheila. “He wanted to be the president,” Lena explained. “He used to say that his goal was to be the president of the United States.” Their ambitions were mutual. “By the time I met Barack, I was thinking about politics as well, with aspirations of being the mayor.” Lena told him, “I could see myself being the mayor of the city of Chicago. That’s where I’d want to end it, and his thing was oh no, he wanted to go on to be the president.” While Barack had told Mike Kruglik and Sokoni Karanja that being mayor of Chicago was his ultimate goal, Lena firmly declared, “That’s not what he’s telling me.”

Lena understood their similar trajectories. “You start to feel and realize your potential, so as you’re growing in this arena, why wouldn’t you think about those things? … That’s why I thought about the mayor,” and for Barack “it’s because of what he realized as he’s growing in the public arena and realizing his potential.” She knew that getting a law degree was “absolutely” his first step toward electoral politics. Across those months, “our conversations—they were real. They were genuine, sincere conversations about ourselves and what we wanted to do, what we were doing, what we were thinking of.” Lena knew Barack lived with someone. “I hear of her,” Lena explained. “Asian woman.” No, “I never met her…. I remember him saying she was Asian.” What did Barack tell Lena about that relationship? “He gave the impression that they lived together more because of convenience—they both needed a place to stay.”