По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

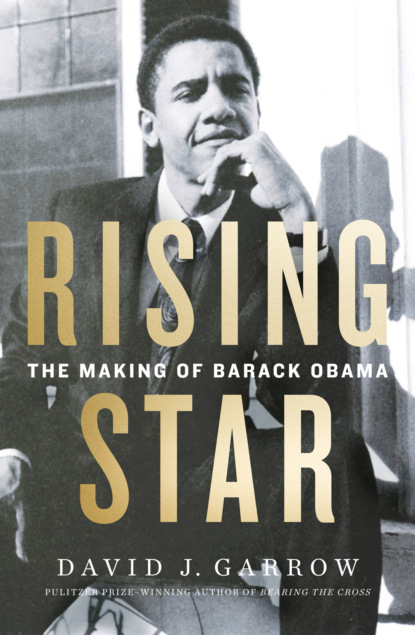

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Rob appreciated that Barack was “very much a synthetic thinker,” just as other classmates had sensed from his many summary expositions, and Rob realized as well that virtually everyone around them “recognized from the start” that Barack was “exceptional.” Rob understood that Barack’s time in Chicago had been “an extraordinary experience for him,” and although Rob has no memory of any such conversation, one of his closest friends vividly remembers a phone call early in Rob’s time at Harvard in which Rob said he had just met the first African American president of the United States.

“Barack and I both looked at law school as an intellectual playground, a place to develop ideas, to have fun with ideas,” Rob explained. “There is no question, when he was in law school, his path in his mind was to be a politician. That is where he was going, and that was crystal clear from day one of law school,” along with definitely returning to Chicago upon graduation. During their conversations, Rob learned that “Barack recognized he had exceptional talents, and that that was a gift from God, that was something special.” Barack “felt a great moral obligation to use” his “special gifts” to “help people … and that was very palpable, very real, and very deep.” Just as Sheila Jager had heard Barack speak about his destiny, Rob too understood that Barack had a sense of himself that was rooted in his experiences in Roseland. “The way he described it to me,” Rob recalled, during “long deep conversations … he pictured an elderly African American woman sitting on a porch and just saying to him, ‘Barack, you’ve got special gifts. You need to use them for people.’ That was a very deep-seated belief. There’s no question about that,” even in the fall of 1988. Rob also knew that Barack’s identification as black “was a choice,” and that “making choices about identity did limit personal choices, and that pained him.”

Barack “spent so much time together” with Cassandra “Sandy” Butts that a mutual friend explained how “everybody thought they were dating, even though I don’t think that was ever the case.” As Jackie Fuchs forthrightly put it, voicing a perception widely shared among female classmates, Barack “gave off zero sexuality…. He came off as completely asexual.” His relationship with Sandy, who was four years younger and whose parents had divorced before she was a year old, had an older brother–younger sister closeness.

“When I first met Barack, I thought he was this black guy from the Midwest, and he did not volunteer his background, other than coming from Chicago,” Cassandra explained. “I didn’t know that Barack’s mother was white until a couple of weeks into knowing him. It wasn’t something that he volunteered.” Sandy was interested in Africa and had visited Zimbabwe and Botswana as an undergraduate, and only after Barack mentioned his trip to Kenya did his family story emerge: “My mother is white.” Like Rob, Sandy also soon realized that Barack’s years in Chicago had been “the most formative” of his life, and “he talked about how powerful the position of mayor of Chicago was,” just as he had told Mike Kruglik and Bruce Orenstein months earlier. Barack “certainly saw in Harold Washington a model,” one who was “incredibly influential,” and “his ambition was to eventually run for mayor.” In Cassandra’s memory there was no question Barack “wanted to be mayor of Chicago, and that was all he talked about as far as holding office…. He only talked about being mayor, because he felt that is really where you have an impact. That’s where you could really make a difference in the lives of those people he had spent those years organizing.” She remembered too that “Barack used to say that one of his favorite sayings of the civil rights movement was ‘If you cannot bear the cross, you can’t wear the crown,’ ” a rough approximation of Martin Luther King’s January 17, 1963, statement—“The cross we bear precedes the crown we wear”—that was featured in the epigraph of the King biography that had been published midway through Barack’s time in Chicago.

Cassandra believed Barack’s intellectual seriousness made him “a bit of a geek in law school,” but his Chicago experiences gave him a real-world grounding most of his younger classmates lacked. She remembered a 1L discussion among black students about whether the preferred label should be “black” or “African American.” “Barack listens to all of this, and near the end … he basically makes the point that it was kind of this false choice, that whether we’re called ‘African Americans’ or ‘black,’ it really doesn’t matter, what matters is what we’re doing to help the people who are in communities that don’t have the luxury of having this debate.” Cassandra thought of Barack as “African and American,” with “a sense of direction and focus” that distinguished him. Compared to his younger classmates, Barack seemed “incredibly mature,” with a “very calm” demeanor, and Cassandra thought “Barack was as fully formed as a person could be at that point in his life.”

An informal study group emerged that included David Troutt, Gina Torielli, and Barack. They met sometimes at the BLSA office or at Torielli’s apartment. On one occasion, when Barack was outside smoking, Gina worried that “my landlord was going to call the police” after seeing a black man on the front porch. On another, when everyone was saying what their dream job was, Barack “said he wanted to be governor of Illinois.” Still, most of Barack’s study time was spent with Rob, and when the law school’s 1989 Yearbook appeared some months later, an early page featured an uncaptioned photo of Barack sprawled on a couch listening as a smiling Rob spoke while holding a loose-leaf notebook. “When I think of those two that year,” Gina Torielli explained, that picture “is how I remember often finding them.” The photo captured the ring on Barack’s left index finger that he had worn ever since his first year at Oxy. Rob remembered precisely when the picture was taken. “I was explaining macroeconomics to Barack, and … we also had an extended discussion about the national debt in that session and how and whether it mattered.” It was no accident that Cassandra thought Barack something of a geek, or that virtually everyone in Section III looked up to Rob and Barack as the smartest minds in their midst.

Barack was more forthcoming with Rob than with anyone else at Harvard, indeed with anyone other than Sheila and Lena. Even though Barack “never mentioned mayoral politics” and never said anything “that would suggest to me that he had his sights on mayoral politics,” it was clear “he was just extremely politically ambitious” and “wanted to go as far as he could. There was no doubt in my mind he was thinking presidency” and “he shared that with me at the time.”

Obama’s classmates could see that too. We “knew he’d be in politics. That was obvious right from the start,” Sherry Colb explained, and Lisa Paget agreed that Barack “was clearly going to be a politician.” David Attisani thought that Harvard’s classrooms were “something of a rehearsal for him for public life,” that “he was getting himself ready” and seemed to be “self-consciously grooming himself for … some kind of public life.” In retrospect, Jackie Fuchs thought Barack “had already decided that he was a future president,” and wondered if his self-transformation mirrored that of her past bandmate, Joan Jett. “I’m sure Barack as a child was perfectly ordinary, just like Joan was. Until the moment he decided that he was a star.” Fuchs was not enamored of the 1988 Barack—“in law school the only thing I would have voted for Obama to do would have been to shut up”—but among the 1Ls who socialized together, David Troutt believed there was “none more careful, more guarded about his personal life than Barack.” David Attisani likewise viewed Barack as “a very private guy” who was “quite cautious about where he appeared socially.”

One Thursday evening, several young members of Section III, including Scott Sherman, a 1988 highest honors graduate of the University of Texas at Austin, decided to head down to Harvard Square to drink. Seeing Obama studying nearby, Sherman invited him to join the group, but Barack demurred. “No, you young guys go on down and have fun. I have work to do here,” and Barack’s comment left Sherman “feeling like a sophomoric frat boy. He was serious” and “he was not wasting his time at the law school,” Sherman recalled. “He was there for a reason,” and there was no gainsaying the five-year age gap between Barack and most of his fellow students.

Years later, classmates pictured how Barack appeared back then. “He always wore the same ugly leather jacket,” Jennifer Radding said, and everyone remembered seeing him smoking outside Harkness Commons—“the Hark”—or, during the winter, in a basement smoking room that was one of the few authorized locations after a Cambridge antismoking ordinance had taken effect eighteen months earlier. “He really did smoke a lot,” Mark Kozlowski recalled, and sometimes in the basement, Barack talked with Kenyan LL.M. student Maina Kiai, who also had arrived that fall. Kiai remembered him “always asking questions about Kenya and Africa,” and “we talked a great deal about poverty in the USA.” Diana Derycz also recalled Barack as a “big smoker” who was “outside smoking” before classes even in winter. Sarah Leah Whitson believed that by 1988 at Harvard Law smoking was a symbolically transgressive act that set one apart from the student mainstream. Rob Fisher thought that Barack “enjoyed it,” and Lisa Paget remembered that when Barack was “walking on campus in his leather jacket with his typical cigarette in his hand, he had swagger.”

Barack was also among several dozen 1Ls who signed up to do scut work—“sub-citing,” as in substantive citation checking—for the Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, one of the law school’s student-run journals that welcomed 1L participation. At the end of October, Barack’s sister Maya, who was a freshman at Barnard College in Manhattan, came up for a weekend, including a Halloween-evening dinner party at Barack’s apartment for which ten or so people were encouraged to come in costume. Rob and Barack’s 1L friend Dan Rabinovitz and his buddy Thom Thacker came wearing whale outfits inspired by the freeing that week of two creatures that had been trapped in the ice off Point Barrow, Alaska.

“I remember from early on thinking that Barack was the single most impressive individual I’d ever met,” Rabinovitz recalled, and that his Somerville apartment “seemed incredibly hip.” Barack had “made it a great place to live,” and his taste for Miles Davis and similar musicians was evident from “the wonderful jazz playing in the background.” Dan had also been an organizer, and he agreed with Barack “that to really deal with the fundamental issues in people’s lives, you needed to engage the political system.” Dan too remembers how Barack “made clear absolutely it was his intention to go back to Chicago and to be involved politically.” Thom Thacker vividly recalls that Halloween evening, perhaps because Barack “possessed a magnetic charm” or more likely because Maya was now “drop-dead gorgeous.” But either that evening or a few days later, Thom would recount how “I remember Dan remarking to me that he thought Barack would be president of the United States one day.”

On November 8, 1988, George Bush handily defeated Michael Dukakis to keep the presidency in Republican hands. “Dukakis’s loss was a major loss, and we were feeling it,” David Troutt recalled, but Mark Kozlowski remembers David Rosenberg beginning Wednesday’s Torts class with a caustic quip about the Supreme Court aspirations of one of his favorite colleagues: “Larry Tribe can unpack!” Rosenberg’s respect and affection for Rob and Barack was now expressing itself in a different way, because when their favorite NBA team, the Chicago Bulls—“We were both big Michael Jordan fans,” Rob says—was in Boston that night to play the Celtics, Rosenberg gave them “like second row” tickets so they could watch an “awesome” 110–104 Bulls victory in which Jordan scored fifty-two points.

By early November, Rob, Barack, and Mark Kozlowski had agreed to work together on the upcoming spring semester Ames Moot Court exercise, and they also enlisted Lisa Hertzer, another member of their small Legal Methods class and a 1988 Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Stanford. The Legal Methods course had proven more daunting for 3L instructor Scott Becker than for most of the 1Ls. “Barack was so far ahead of the curve intellectually,” Becker remembered, that often sessions featured the “hyper-ambitious” Obama explaining, “I think this is what Scott means by that,” although never in a way that embarrassed Becker.

Barack and Rob were also beginning to think about summer jobs for 1989, and Barack wanted to return to Chicago. Barack’s old friend Beenu Mahmood, who had welcomed him there in 1985 while he was a summer associate at Sidley & Austin, was now in his third year as a lawyer in Sidley’s New York office, and “I suggested that he seriously look at Sidley,” Beenu remembers. Barack had kept in regular touch with Beenu, who believed by 1988 that “Barack was the most deliberate person I ever met in terms of constructing his own identity.”

Sidley actively sought out top 1Ls, and Beenu recalls speaking with Sidley managing partner Thomas A. Cole about Barack. Well before Christmas, his résumé arrived at Sidley’s Chicago office, where 1972 Harvard Law School graduate John G. Levi oversaw the firm’s recruiting at his alma mater and 1976 Northwestern Law School graduate Geraldine Alexis headed up Sidley’s minority associate recruiting effort.

On the Friday after Thanksgiving, Barack learned the surprising news in that day’s New York Times: “Albert Raby, Civil Rights Leader in Chicago with King, Dies at 55.” A memorial service at the University of Chicago’s Rockefeller Chapel attracted more than a thousand mourners, and Teresa Sarmina, one of Raby’s former spouses, spoke of how he “would get excited about a person and the potential he could see in that person.”

In Cambridge, the last two weeks of fall semester classes featured a December 7 meeting with Ian Macneil that about 60 percent of Section III attended. “A wide range of complaints were voiced,” Macneil recalled, and tensions were raised further because the final exam in the yearlong course would not take place until late May. Only in their final week of classes in mid-December did Section III learn that its other exams would take place on the afternoons of Monday January 9, Wednesday the 11th, and Friday the 13th. With Civ Pro teacher David Shapiro leaving for Washington, students’ marks on the two-and-a-half-hour open-book midyear test would constitute half of their eventual grade on Harvard’s somewhat odd A+, A, A-, B+ B, B-, C-, and D eight-point scale. Shapiro posed only two essay questions of equal weight, one involving securities fraud and the other concerning an interlocutory (interim) appeal involving hundreds of lawsuits stemming from a hotel fire. No one could have found it easy. Two days later, Richard Parker’s three-and-a-half-hour open-book Crim Law exam posed three questions weighted at 50, 25, and 25 percent. The first posed a hilariously complicated fictional scenario involving a racially profiled terror suspect carrying cocaine who bumps into a knife-wielding drunk who then stabs a passerby. Students were instructed to “respond specifically to all” of six analytical issues. The shorter second and third questions were visibly easier, with the former offering as one of two options an essay on the Burger and Rehnquist Courts’ rulings on searches and interrogations. The third requested a response to a quotation asserting that changes in substantive criminal law doctrines offered a better chance of combating racism than did procedural reforms. On Friday the 13th, Section III’s exam week ended with a three-hour, open-book, two-question Torts exam from David Rosenberg. “Careful organization will be highly valued, as will conciseness and clarity of presentation,” the exam advised. One question dealt with a gang fight prompted by a movie about gang warfare, the second probed a manufacturer’s liability after a polio vaccination of a child infected the youngster’s father.

With his first three exams complete, Obama flew to Chicago for ten days before spring semester classes began. Staying with Jerry Kellman’s family, Barack immediately learned that Al Raby’s death was not the only sadness that had befallen his Chicago friends. When Barack left Chicago in mid-August, Mike Kruglik replaced Greg Galluzzo as DCP’s consultant-adviser, and in Mike’s first heart-to-heart conversation with John Owens, Johnnie confessed that he was losing a struggle with cocaine addiction. “I was shocked,” Kruglik recalled, but he immediately arranged for Owens to enter a thirty-day residential treatment program on Chicago’s North Side and drove him there to help him check in.

A month later, Johnnie was back at DCP, but the group’s core members felt he had not been prepared to fully shoulder the weight of being executive director. “John was good, but he was not Barack,” Betty Garrett explained. “There was no one in my eyesight that would have been able to fill Barack’s shoes.” Aletha Strong Gibson remembered that they all realized that Owens “wasn’t quite ready” to assume such “a high-pressure position.”

Jean Rudd and Ken Rolling at Woods felt similarly. “When Barack left, Johnnie was really very feeling kind of abandoned,” Jean recalled. “He wasn’t quite ready to be in charge yet” and “just wasn’t confident at that point.” Ken agreed that “John became director before his time.” When Barack learned what had happened, he discussed the situation with Jean, Ken, and Jerry, who remembered that he was “deeply concerned about it” because “he’s feeling responsible.” Kellman also thought that if “DCP blows up in a scandal,” it could hurt Barack’s reputation. Owens recalled that Barack “suggested that I change the name of DCP” because he “figured if I didn’t do a good job with it or something went wrong, it wouldn’t come back to haunt him.” Johnnie saw Barack as deeply strategic about his own future, but Barack refused to acknowledge that. “I was pressing him one time, and he got angry. ‘No! I said no!’ ” But Barack’s exceptionally rare outburst did not alter Owens’s firm belief.

During Obama’s first semester at Harvard, the Illinois legislature had finally approved a comprehensive Chicago school reform bill, which Chicago United’s Patrick Keleher praised as “a fantastic bill,” one that called for every Chicago public school to be governed by an eleven-member Local School Council composed of six parents, two area residents, two teachers, and the principal. UNO and Gamaliel had played a significant role in the victory, but the hard work of implementing it still lay ahead.

Barack had corresponded regularly with Mary Ellen Montes throughout the fall. “The letters came for a while,” Lena remembered, but then there was “a determining letter that was sort of like we weren’t going to write to each other anymore, and so we didn’t.” By January 1989, Lena was involved with someone else, and she and Barack were never again in touch. In Lena’s and Sheila’s absence, and with his friendship with Johnnie now seriously strained, Barack’s two strongest Chicago relationships were with Kellman and Kruglik, and during his ten days back in Chicago, he readily helped both of them with their ongoing organizing work.

Jerry was now fully occupied in Gary, Indiana, and thanks to both Woods and the Diocese of Gary, he had just publicly launched Lake Interfaith Families Together (LIFT), named after the county that encompassed much of northwest Indiana. In Chicago’s south suburbs, Mike was rapidly growing the South Suburban Action Conference (SSAC), and in January 1989, he hired a new young African American organizer, Thomas Rush, a 1988 graduate of Haverford College.

Rush recalled that even during his first long conversation with Kruglik, Mike mentioned Barack, with the implication being that “this guy was special within organizing.” Mike asked Barack to call Thomas, and the next morning they met for forty-five minutes over coffee. Knowing that Barack was at Harvard, Rush expected someone arrogant, but instead he thought Obama was calm and self-assured, with an “even temperament.” Rush remembered that when Barack mentioned Jeremiah Wright, it was “almost like his mind left for a minute” as Barack looked away. When Thomas asked how attending Harvard Law School would connect to further organizing work, Barack said, “I don’t know that I’ll be directly involved, but this will always be a process that I support, whatever I do.”

A few days later, during a LIFT training in Gary, which Kruglik and Rush attended, Obama, along with Kellman, led the day’s sessions for a group of some forty people. At the end of the day, Rush rode back into Chicago with Barack. As Thomas recalled it, Barack mentioned “that he would like to find a good relationship,” ideally “a woman with the body of Whitney Houston and the mind of Toni Morrison.”

Before Barack returned to Cambridge, he had his summer job interview at Sidley & Austin’s Chicago office. “We brought in all of the kids who had a Chicago connection,” John Levi recalled, for twenty-minute conversations with two or more Sidley lawyers. African American applicants generally were seen by a trio of Levi, Geraldine Alexis, and Alexis’s chief lieutenant, Michelle Robinson, the 1988 Harvard Law graduate who had played such an active role in BLSA before joining Sidley eight months earlier.

“Michelle I distinctly remember saying, ‘I cannot see him. Will you please make sure you can see him?’ ” Levi remembered. He did, and “I was wowed” by Obama. “I thought he was phenomenal. He was one of the best interviews I’ve ever had, really.” He recalls that Obama demonstrated “poise and sparkle” and clearly was “a compelling person.” Geri Alexis had a similar reaction. “I remember very vividly” speaking with Barack. “He impressed me so much that I called down to the recruiting office, and I said, ‘We really need to give this guy an offer before he leaves the building,’ and they said, ‘Well, we don’t do that for 1Ls,’ and I said, ‘You’re going to do it for this one,’ ” and they did.

John Levi concurred. “I called Michelle later in the day and said, ‘Boy, did you miss a good one,’ ” and Robinson replied, “ ‘That’s what everybody is telling me.’ ” As Levi recalled, Barack “accepted quickly too.”

Spring classes began on January 25, and Barack, Rob Fisher, Mark Kozlowski, and Cassandra Butts all chose for their elective 18th and 19th Century American Legal History, taught by assistant professor William “Terry” Fisher, a 1982 Harvard Law graduate who had clerked for Justice Thurgood Marshall. The three-hour-a-week lecture class covered “the formative era of American law,” with emphasis on the changes between the Revolution and the Civil War, especially regarding slavery. Famous cases like Marbury v. Madison and McCulloch v. Maryland were supplemented by doctrinal-specific readings addressing contracts, torts, property law, criminal law, and the status of women. The semester’s final three weeks were devoted to slavery, with recent articles by leading scholars like Paul Finkelman and Robert Cottroll playing a central role.

Section III’s Civ Pro also met for three hours a week, with Northeastern’s Stephen Subrin replacing David Shapiro. Some students found Subrin likable, while others felt he was a letdown compared to Shapiro. Contracts with Ian Macneil continued for three hours a week while Three Speech reported an unsupported rumor that “the Scowling Scot” might remain at Harvard more than one year. Lisa Hay occasionally included a crossword puzzle, and one had the clue, “He pauses before speaking.” The correct answer was “Obama.”

Rob Fisher had stopped attending Contracts—“It was so horrible that I basically skipped all of it”—but Barack remained a regular if sometimes tardy presence. Three Speech’s list of “highlights” included “February 21: Obama knocks on contracts door, 9:21 A.M.,” more than twenty minutes late. Ken Mack remembered that Barack was one of Macneil’s “favorite students,” and Macneil recalled that he had “such a commanding presence…. I was always a little too impatient in class, so if students went off the track, I would interrupt before I should. When I did that with Barack, he said ‘Let me finish.’ He wasn’t rude, just firm.’ ”

Spring’s most weighty course was five hours a week of Property Law, taught by Mary Ann Glendon, a 1961 graduate of the University of Chicago Law School who had joined the Harvard faculty in 1987. She assigned the class A. James Casner et al.’s 1,315-page Cases and Text on Property, 3rd ed. On the first day, Glendon called on Barack, mispronouncing his surname by making it rhyme with Alabama. Barack corrected her. Paolo Di Rosa thought that “was kind of a nervy thing to do,” but Barack “had the confidence to do that without being rude about it.”

Three Speech regularly captured how Glendon’s excellent sense of humor made for a relaxed classroom atmosphere. “I assume that a lot of you are in some relation to Harvard,” Glendon suggested. “What’s that relation? What? No, I don’t mean ‘serfdom.’ ” On another occasion, a student asked, “How long do you have to, you know, ah, live together, for these common-law marriages?” and Glendon drily responded, “Why do you ask?” Glendon was a widely popular teacher, and Rob Fisher remembered her as “an excellent professor” whom he and Barack visited for some “very open-ended, interesting intellectual discussions.” Fellow students recall both Barack and Rob as regular classroom participants. Ken Mack thought Glendon was “very interested in what Obama had to say in class” and “liked him a lot.” Edward Felsenthal, a 1988 magna cum laude graduate of Princeton, would “vividly remember” Barack as someone who “talked all the time” in Property. There were some “heated battles between Barack and Mary Ann Glendon,” Felsenthal recalled, because Obama “objected to some pretty core tenets of the common law of property.” So “they went at it,” and “nobody else sparred like he sparred with her.” Rob remembered a time when Glendon asked why a court had set aside a condominium bylaw barring children as residents. Barack spoke up, saying, “Folks gotta live someplace,” and “everyone laughs,” but the crux of his response—the reasonableness standard—was indeed key. That “tells you a lot about how he was thinking about” legal questions while at Harvard, Rob explains. He and Barack “loved” Glendon’s “great” class, even though twenty years later Glendon would refuse to appear on the same platform with her former student because of her intense opposition to abortion.

In early February, the Harvard Law Record and the Harvard Crimson gave front-page coverage to news that the student-run Harvard Law Review had elected an Asian American 2L as its new president and an African American woman as one of its two supervising editors. Crystal Nix, a 1985 Princeton graduate who had been a New York Times reporter prior to law school, was the first black person ever elevated to one of the Review’s top masthead positions.

Far more controversial news landed a week later when Harvard president Derek Bok, a 1954 graduate of the law school who had served as its dean for three years before being elevated to the presidency in 1971, unexpectedly chose forty-four-year-old Robert C. Clark as the new law dean. Clark was “generally well-liked by students,” the Crimson reported, because he was an excellent classroom teacher, but some of his more liberal colleagues complained about the selection of the conservative law and economics proponent. In the Boston Globe and the New York Times, Gerald Frug called Clark “a terrible choice” and Morton Horwitz denounced the selection as “a disaster for the law school,” asserting that Clark had opposed the appointments of women and minority professors. Clark rebutted Horwitz’s claims as “untrue” and “terribly unfair,” while three more professors attacked Clark. In contrast, prominent liberal constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe spoke positively about Clark, and a Wall Street Journal editorial praised the selection. Several weeks later the controversy seemed to subside when the faculty unanimously promoted Randall Kennedy and Kathleen Sullivan to full professor, the third black male and the sixth white woman holding tenured appointments.

At 12:30 P.M. on Thursday, February 23, the 1Ls’ exam grades were finally distributed. Barack and Rob had mixed reactions. In David Rosenberg’s Torts, Rob earned a straight A, and Barack something similar, but in Richard Parker’s Crim Law, Rob received only a B+, and as he remembered, “Barack and I both didn’t like the grade we got.” Many classmates would have been overjoyed to receive a B+, as they confronted lower grades than they had ever before received. For some, the “effect was devastating,” but not so for Barack and Rob, who plunged into the Ames Moot Court assignment that would culminate with a faux oral argument on Thursday evening, March 23, the night before spring break began.

The ungraded Ames exercise had four written assignments: an initial “issues analysis” of the faux case, an outline of the brief to the three-judge faux court, a draft of the brief, as well as the final brief. Throughout the six weeks, students had four conferences with Scott Becker, the twenty-five-year-old 3L from Illinois who had led their fall Legal Methods class and was now the teams’ adviser. Barack and Rob took opposing sides, with Mark Kozlowski as Barack’s partner and Lisa Hertzer as Rob’s. Their case involved two issues related to inside information and the stock market: the first was whether a clerical employee had violated the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 in buying stock based on a research report she had proofread, and the second was whether sharing that information with a friend with whom she then twice purchased stock represented a conspiracy punishable under the RICO Act of 1970. Each student team was given a twenty-two-page faux indictment of the two defendants, “Janine Egan” and “Jennifer Cleary,” that gave the facts that had led to their convictions, which were now on appeal.

Early on, Barack and Rob took the exercise “extraordinarily seriously,” Mark thought, and exhibited great determination to win the competition. But once it sank in that it was ungraded, their emerging desire to graduate magna cum laude—5.80 or better, with 6 representing A minus—took precedence. Rob knew that for Barack “it was very important to him to get magna cum laude … to demonstrate that things”—i.e., a Harvard Law School diploma—“weren’t given to him” as a result of how affirmative action may have helped him win admission. Mark Kozlowski realized that Barack and Rob “both decided they were going to make magna cum laude,” and that made them “less serious about” the Ames exercise as it proceeded.

In advance of the two pairs’ oral arguments before Professor Hal Scott and two other faux judges, Mark and Barack completed their thirteen-page brief, with Barack writing the insider trading argument and Mark handling the RICO question. Barack contended that Egan’s work “inevitably” and “necessarily” would have made her aware that the materials she had proofread were nonpublic information, which she then misappropriated in violation of the 1934 statute. Barack flubbed badly in referencing the U.S. “Court of Appeals of the Second District,” when he should have written “for the Second Circuit,” and a careful eye would have caught misspellings and bad grammatical errors, such as “recieve,” “the harm done by insider trading are diffused,” and “employes like Egan regarding the in no way mitigates.” It was visibly sloppy work, especially compared to what Mark offered in the RICO section. “The Egan-Cleary enterprise victimized not merely” Egan’s employer, they argued in conclusion, “but the integrity of the securities market as a whole.” Oral argument turned into “a bit of a fiasco,” Kozlowski remembered, when he “got into a fight” with Professor Scott. “Barack was somewhat angry with me afterward,” Mark recalled, but “by that point” both Barack and Rob were happy to leave moot court behind them.

That same day, Ian Macneil received a letter from the Women’s Law Association, complaining that Section III’s Contracts reading earlier that week had contained sexist material. In dealing with a convoluted contracts problem known as “the battle of the forms,” Macneil’s casebook invoked the phrase “jockeying for position” and then quoted a couplet from Byron’s “Don Juan”: “A little still she strove, and much repented, / And whispering, ‘I will ne’er consent,’—consented.” Given Section III’s history with Macneil, some classmates knew as soon as they read those lines that controversy would follow. Bonnie Savage, the WLA chair, wrote, “Repeated instances of sexism in both your contracts textbook and your classroom discussions have been brought to the attention of the Women’s Law Association.” She said the Byron quote reflected “sexist attitudes” and “has no place in a contracts textbook.” Indeed, “by using sexist language, you encourage sexist thought and, in essence, promote hostility against women.”

Macneil later acknowledged, “I knew the class considered me a first-class bastard,” but the WLA aspersions were “a bolt out of the blue.” When classes resumed after spring break on Monday, April 3, every member of Section III and every member of the law school faculty received an eight-page, single-spaced letter of rebuttal that Macneil addressed to the WLA. “Throughout the year I have had a great many complaints about the course from students of both sexes,” but only two had anything to do with gender, and at the December 7 grievance session, “not a word was said about any alleged sexism.” Macneil declared that “this whole affair … reeks of McCarthyism” and said its roots lay in his efforts “to insist that students act like professionals in the classroom respecting participation, preparation, attendance, and promptness.” Two days later, Macneil reiterated his mandatory sign-in policy, saying he had referred the names of three regular absentees to law school administrators. A number of students spoke up in support of Macneil, and others asked about the upcoming, much-feared final exam.

A week later, the Boston Globe published a lengthy story, highlighting “Macneil’s tough classroom manner” plus “his volatile temper and argumentative style.” The Globe quoted Bonnie Savage as saying the WLA feared Harvard might give Macneil a permanent appointment. More significant, Jackie Fuchs told the paper that Macneil “goes out of his way to avoid being sexist,” and that she, like a good many other Section III women, felt that WLA’s “letter was really out of line.” The Harvard Law Record’s own extensive coverage included multiple students noting that they had been given no notice that the law school’s long-dormant attendance policy might suddenly be enforced.

Within Section III, the news coverage generated something of a pro-Macneil backlash. Brad Wiegmann remembered feeling badly for Macneil because “people were treating it as if it was the civil rights movement over whether you had to attend your Contracts class.” Lisa Hay believed Macneil “got a raw deal” from Section III, and David Troutt agreed he was “a decent guy” whose relational view of contracts “actually was probably a good theory.” Among students who later became contracts lawyers, some, like David Attisani and Shannon Schmoyer, said that Macneil’s course had been of no professional value, but an equal if not greater number strongly disagreed. Steven Heinen “really appreciated his very practical approach to contracts,” and said Macneil’s teaching has “served me well” in later years. David Smail, who would become general counsel of a prominent international hotel corporation, remembers Macneil as “a pompous asshole,” but “as much as I despised the man,” Macneil’s “relationship approach to contracts is one that I really fervently believe in, and I preach it every day in my business.” As a general counsel, “you’re living with the contract rather than just drafting it,” and Macneil’s perspective “is a very powerful way of looking at contracts.”

Soon after the news stories, law school administrators convened a small meeting with Macneil and several students. Ali Rubin remembered that Barack had “distanced himself from” the complaints, and Mark Kozlowski knew that Barack felt “there was nothing we could do about it.” Rob remembered that “Barack and I both felt that the revolution was a little over the top,” and by April, Obama was playing “a mediating role” and was “calming people down.”

Lauren Ezrol, one of Section III’s official representatives on the Law School Council, recalled being summoned to the meeting. “It was Barack, me, and then everyone else in the room was an administrative type, like a dean of students, and Macneil was there.” They were “supposed to try to work out the issues,” but rather than some dean taking the lead, instead Barack “was the one who with great confidence talked to Macneil” and “worked out whatever resolution” was agreed to. Ezrol thought Obama was “unbelievably impressive,” and his interaction with Macneil was entirely amicable. “I was just blown away,” Ezrol remembered, “to see someone operate with such ease and confidence and maturity. It was remarkable.” Years later, just prior to his death, at age eighty, in 2010, Macneil recalled that Obama was “a calm person in a class that was not altogether characterized by people being calm,” adding that it was “obvious that his class respected him.”

Barack and Rob continued to visit David Rosenberg even after their fall Torts class ended. Rosenberg believed they should expose themselves to “the best minds on the faculty,” and as the time for choosing 2L fall courses drew near, Rosenberg recommended well-known constitutional law teacher Laurence H. Tribe. For most 1Ls, it would take a good deal of gumption to approach one of Harvard’s most prominent professors, Rosenberg knew, but on Friday, March 31, Obama did so, and Tribe was immediately taken by this heretofore unknown student. As Tribe remembered it, their first conversation lasted for more than an hour, and before it ended, Tribe asked Obama to become one of his many research assistants, which Tribe had never asked of a 1L who had yet to take one of his courses. Tribe wrote his name—“Barack Obama 1L!”—on that day’s desk calendar page, and soon Barack drew Rob Fisher into this relationship with Tribe as well.

When word spread among their close aquaintances that both Obama and Fisher were now working for Tribe, Ken Mack can remember thinking how astonishing that was. Tribe was so impressed by Barack that he mentioned him to his colleague Martha Minow, a 1979 Yale Law School graduate who had clerked for Justice Thurgood Marshall before joining the Harvard faculty in 1981. Minow was always interested in students from Chicago, because she had grown up in the city’s northern suburbs and her father, Newton Minow, who had served as chairman of the Federal Communications Commission during the Kennedy administration, was now a Sidley & Austin senior partner. Martha told her father about Tribe’s impression of Obama, and he picked up the phone and called John Levi to ask if Sidley’s Harvard recruiters knew about this 1L who had wowed Laurence Tribe. Levi had a ready answer: “We’ve already hired him…. He’s coming here for the summer.”

Before Barack began studying in earnest for late May’s final exams, he faced a trio of choices. Wednesday night, April 12, was the informational meeting for 1Ls interested in the weeklong writing competition that would take place in early June to select thirty-eight members of the Class of 1991 for the prestigious Harvard Law Review. The next evening was the initial editors’ meeting for the upcoming year’s Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, which Barack had worked on as one of thirty 1Ls during the preceding months. One 2L editor, Sung-Hee Suh, remembered Barack “talking very calmly” during a sometimes heated discussion of hate speech, “articulating both sides” of the debate as students of color and free speech absolutists disagreed vehemently on the issue. She recalled thinking he was very “calm, cool, and collected.” Outgoing managing editor Wendy Pollack noted that Barack did not participate in the journal’s election for the upcoming year’s board, a clear sign that he intended to try for the premier Law Review instead. Barack had asked David Rosenberg whether he should do so, and Rosenberg said, “Yes, of course.”

April 13 was also preregistration for fall classes, but the 1Ls would not learn until May 8 whether or not they had gotten into popular, oversubscribed courses, such as Laurence Tribe’s section of Constitutional Law. Cassandra Butts remembered that “Barack did not get in,” but some “special pleading” with Tribe quickly succeeded.