По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

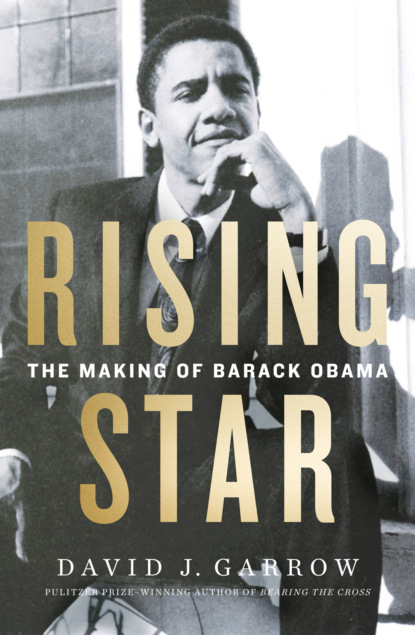

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Monday, May 15, was the last day of spring classes, and Lauren Ezrol and Michelle Jacobs both recall Obama telling their Contracts class that anyone who would like a copy of the outline he had prepared from both semesters’ worth of notes was welcome to it. Jacobs remembered that the document was easily 100, if not 150, typed pages and “had little jokes in it. It was great.” Barack had many takers, because almost everyone agreed with Greg Sater’s assessment that Barack “was the smartest in the class.” Lauren Ezrol agreed: “he just seemed smart and impressive and so sure of himself and well-spoken and older.”

Barack had his Legal History take-home exam on Monday, May 22, followed by Section III’s trio of tests: Property on Wednesday afternoon, Contracts on Friday morning, and Civ Pro on Tuesday, May 30. Property and Civ Pro would cover just the spring, but Macneil’s Contracts exam would determine everyone’s entire grade for the full year, six credits, and “people were really worried,” Brad Wiegmann remembered. David Attisani asserted that Section III suffered “mass hysteria” in advance of the Macneil final.

Mary Ann Glendon’s Property exam was an unpleasant surprise to many members of Section III, with Mark Kozlowski remembering that some of the questions “had nothing to do with the stuff we had covered in class.” Steven Heinen agreed, recalling that students first encountered the word “easement” only on the test. Half of the test, involving six specific questions, concerned Native Americans on “Vintucket” island who were being pressured to sell their seaside property to an aggressive celebrity. An estranged, unmarried couple’s frozen embryos, a building lease, and a “takings” issue constituted the balance of Glendon’s exam.

Friday morning, May 26, brought literal shrieks of horror when angry students confronted Ian Macneil’s bizarrely demanding Contracts exam, which instructed them to write their answers “ONLY INSIDE THE BOX AFTER EACH QUESTION” on the twenty-five-page test. The first, three-part, twenty-minute question asked whether a U.S.–Soviet nuclear missile treaty did or did not constitute a contract, depending on how that concept was defined. An answer of up to fourteen lines was permitted. Ten subsequent questions, ranging from ten to twenty-five minutes apiece, involved, among other topics, a nephew cut out of a will on account of his race and the sale of fourteen hundred convertible sofas. Student complaints raged. Following the Memorial Day weekend, Section III’s “very intense year,” as Paolo Di Rosa termed it, ended with a straightforward two-question open-book Civ Pro exam from Stephen Subrin.

Two hundred eighty-five 1Ls—179 men and 106 women—had decided to enter the Harvard Law Review’s writing competition, and only one day separated the end of final exams and the distribution of the HLR materials. The weeklong assignment consisted of two parts. First was a Bluebook test—The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation, then in its fourteenth edition, dated back to 1926, and was the most widely used style manual in legal academia. First-year students had been introduced to the volume’s arcane instructions, especially for abbreviations, the previous fall in Legal Methods, but this HLR competition was their first real opportunity to apply its editing rules.

The second and far more demanding part entailed writing a lengthy essay—in law review parlance a “note”—weighing the merits and demerits of the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in DeShaney v. Winnebago County. A 6–3 majority had rebuffed a claim that a child who suffered severe brain damage at his father’s hands could sue the local child protection agency, alleging a deprivation of his Fourteenth Amendment right to “liberty.” The Fourteenth Amendment covers only state action, and the majority held that state officials do not have a constitutional obligation to protect children from their parents. Justice Harry A. Blackmun filed an emotional dissent.

Barack had a full week to work on the two-part assignment before it had to be postmarked and mailed to the Review’s offices. But on the day it was due, his car would not start, and time was short. He called Rob Fisher, who was just heading out the door, but Rob immediately drove to Somerville and took Barack to the closest post office, where there was a long line. But Rob remembered Barack successfully sweet-talking his way forward, explaining to people that his envelope had to be postmarked by noon.

On the cover sheet that accompanied the submission, the applicant was asked for their summer contact information. They also had the option of indicating their gender and race, and they could provide a brief personal statement if they had experienced any major hardships in life. The writing competition dated back to 1969, but only in 1981 did the Review introduce affirmative action into the process to increase diversity. Only a trio of rising 2L editors who oversaw the selection process would know whether and to what degree those indicators were considered when all entrants’ scores were collated.

At the Review’s offices on the second and third floors of Gannett House, a wooden Greek Revival structure that dated to 1838, newly hired twenty-four-year-old editorial assistant Susan Higgins collected the 285 entries, assigned each a number, removed their cover sheets, and began sending batches of the submissions to the three dozen 2L editors, now scattered at their summer jobs all across the country. They would grade the numbered papers and send them back to Cambridge. Some of those 2Ls wondered whether the choice of DeShaney inadvertently gave 1Ls of one particular political stripe an advantage on their essays. “There were more interesting arguments to be made on the conservative side,” thought Dan Bromberg, a 1986 summa cum laude graduate of Yale, “and so more points to be won” there than for 1Ls who sided with the dissenters. The grading was a multiweek process, at the end of which the 2L officers, including President Peter Yu, the Review’s first Asian American leader, collated the results and factored in the contestants’ 1L grades that Susan Higgins had gotten from the registrar’s office.

Half of the thirty-eight slots would go to the top writing competition scorers; the other half would be determined by an equation based 30 percent upon those scores and 70 percent upon their 1L grades. If a contestant had indicated their minority status, that fact, but not their names, was flagged on their submission. Gordon Whitman, incoming cochair of the Review’s Articles Office and a member of the selection trio, recalled that race was “a little bit of a featherweight on the process,” but it did not count “a whole lot.” Only when the numerical selections had been made did Susan Higgins match the chosen numbers with the individuals’ names: “I was the keeper of the names with the numbers,” she explained.

In midsummer, the successful contestants—twenty-two men and sixteen women—received a phone call, and then a confirming letter, telling them they had been selected. But there was a tangible cost: they would have to leave their highly remunerative summer jobs three weeks early to return to Cambridge before the beginning of fall classes, to start work on the Review’s first issue of the new academic year.

In preparation for the summer, Barack had “sublet the cheapest apartment I could find,” hardly a block north from where he and Sheila had lived in Hyde Park. He also had “purchased the first three suits ever to appear in my closet and a new pair of shoes that turned out to be half a size too small and would absolutely cripple me for the next nine weeks.” Working at a corporate law firm like Sidley reintensified his fears from a year earlier that going to Harvard “represented the abandonment of my youthful ideals.” But choosing Harvard over Northwestern’s full-cost scholarship meant that “with student loans rapidly mounting, I was in no position to turn down the three months of salary Sidley was offering.”

Obama arrived late for his first day at Sidley’s offices at 10 South Dearborn. It was a rainy June morning. Some days earlier, he had spoken by phone with Michelle Robinson, whom Geraldine Alexis and senior associate Linzey Jones had assigned as Barack’s summer adviser because of their mutual Harvard ties. Obama remembered that “she was very corporate and very proper on the phone, trying to explain to me how the summer program at Sidley and Austin was going to go.”

Barack was shown to her office that first day, and Michelle recalled in 2004 that “he was actually cute and a lot more articulate and impressive than I expected. My first job was to take him to lunch, and we ended up talking for what seemed like hours.” She had expected a biracial, Hawaiian-raised Harvard Law student to be “nerdy, strange, off-putting” and even “weird,” but instead Barack was “confident, at ease with himself … easy to talk to and had a good sense of humor,” she recounted. “I was pleasantly surprised by who he turned out to be.” She did however recall that “he had this bad sport jacket and a cigarette dangling from his mouth.”

Rob Fisher was also working at Sidley’s Chicago office for the summer, and he remembered Barack coming by his office soon after they arrived. “He came in one day and said, ‘My mentor is really hot.’ ” As Michelle’s friend and Sidley colleague Kelly Jo MacArthur recalled, Barack wasted little time in making his interest clear. “He would try to charm her, flirt with her, and she would act very professional. He was undeniably charming and interesting and attractive,” but Michelle rebuffed Barack’s repeated suggestions that they do something together. “She was being so professional, so serious,” MacArthur remembered, and she also knew that Michelle was someone with “conservative morals.”

When Barack pressed, Michelle was characteristically direct and told him that as his adviser, it would look bad if they began going out together. Instead, she tried to set him up with several of her girlfriends, just as she did with Tom Reed, another African American 1L summer associate and Chicago native who had been one year behind her as an undergraduate at Princeton. But Barack persisted. Finally, toward the end of June, Michelle reluctantly agreed. “OK, we will go on this one date, but we won’t call it a date. I will spend the day with you.”

On Friday, June 30, they left Sidley’s offices at about noon and walked the few blocks to the Art Institute of Chicago on South Michigan Avenue to have lunch. “He was talking Picasso,” Michelle remembered. “He impressed me with his knowledge of art.” Then they “walked up Michigan Avenue. It was a really beautiful summer day, and we talked, and we talked.”

Barack had a plan. Opening that evening was a movie that already had been the subject of three different articles in the Chicago Tribune: young African American director Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. It was an ingenious idea, but Michelle’s concern about appearances turned all too real when they saw Sidley’s Newton Minow and his wife Jo at the theater. “I think they were a little embarrassed” at being seen together, Minow recalled. After the film, Michelle remembered, “we had a deep conversation about that” and then ended the day “having drinks at the top of the John Hancock Building,” which “gives you a beautiful view of the city.”

“I liked him a lot. He was cute, and he was funny, and he was charming,” Michelle remembered thinking, but after their encounter with the Minows she was all the more determined not to become a subject of office gossip. But when Barack invited her to accompany him to a training he had agreed to do for DCP at one of the Roseland churches, she agreed to go along.

The small group was “mostly single parent mothers,” but she recalled that Barack’s “eloquent” presentation “about the world as it is and the world as it should be” was one she would never forget. “To see him transform himself from the guy who was a summer associate in a law firm with a suit and then to come into this church basement with folks who were like me, who grew up like me,” Michelle recounted, “and to be able to take off that suit and tie and become a whole ’nother person … someone who can make that transition and do it comfortably and feel comfortable in his own skin and to touch people’s hearts in the way that he did, because people connected with his message,” was remarkably impressive. “I knew then and there there’s obviously something different about this guy,” something “special,” and “it touched me … he made me think in ways that I hadn’t before,” Michelle explained. “What I saw in him on that day was authenticity and truth and principle. That’s who I fell in love with” in that church, and “that’s why I fell in love with him.”

Every summer Linzey Jones hosted a picnic at his home in south suburban Park Forest for all of Sidley’s minority attorneys and summer associates. Events like this were standard fare because summer programs at big law firms were aimed at enticing the students into eventually accepting a permanent job offer. Evie Shockley, an African American 1L from the University of Michigan Law School who shared an office with Barack for part of that summer, recalled attending a Cubs game, seeing Phantom of the Opera, and other theater outings. “It was easy to feel like you weren’t working,” she explained.

That weekend day, Linzey Jones remembered Barack and Michelle being “very friendly with each other,” but Barack joined in when many of the men went to a nearby junior high school to play basketball for an hour. Michelle still lived with her parents in their South Shore home, a few miles below Hyde Park, and when she drove Barack back to his apartment, he offered to buy her an ice cream cone at the Baskin-Robbins on the north side of East 53rd Street. Michelle accepted, and ordered chocolate. Sitting outside, Barack told her about working at Baskin-Robbins in Honolulu “and how difficult it was to look cool when you had the apron and the little brown cap on.” Then, in a direct reprise of a question he had posed three summers earlier, also in Hyde Park, he asked Michelle “if I could kiss her. It tasted of chocolate.”

“We spent the rest of the summer together,” Barack later wrote, but a mid-July phone call informed him that a letter inviting him to join the Law Review was in the mail. That good news meant he had to be back in Cambridge by August 16 to work on the Review’s first issue. He took several days to ponder his choice. “We had a conversation about whether or not he was going to do Law Review,” fellow summer associate Tom Reed recalled. “ ‘I’m not sure if I’m going to do it,’ ” Tom remembered Barack saying. “He was clearly on the fence,” and “there was a moment where he was considering whether that was appropriate for his path.” But finally he told HLR as well as Sidley that he was accepting the offer.

Barack and Michelle kept a very low profile at the law firm, and neither Tom Reed nor Evie Shockley had any idea they were dating. Michelle told only Kelly Jo MacArthur. “When she met Barack, things happened pretty quickly,” Kelly Jo remembered. Michelle recalled years later during a joint interview her memories of “the apartment you were in when we first started dating,” the sublet near Baskin-Robbins. “That was a dump.” But bumping into people they knew seemed inevitable. Jean Rudd of the Woods Fund recounted, “I have a very vivid memory of having lunch on Dearborn Street at an outdoor café there, and Barack and this tall, beautiful woman walk by. And he stopped and introduced us and said that ‘This is my boss.’ … We chatted a little while,” and when they left “I remember saying, ‘What a couple.’ ”

One late July evening, Michelle invited Barack home for dinner to meet her parents and brother. Craig Robinson, at twenty-seven years old, was two years older than his sister and also had attended Princeton University. As a senior he was Ivy League basketball’s 1983 Player of the Year, and after graduation he had played professional basketball in Europe for several years before returning home. Craig met Janis Hardiman, a 1982 Barnard College graduate, soon after she moved to Chicago in 1983, and by 1987 they were engaged and living together in Hyde Park while Craig took classes toward an M.B.A. degree at the University of Chicago. Janis and Craig married in August 1988, soon after Michelle’s graduation from Harvard Law School. Ever since Michelle’s senior year of high school, Craig had known that his sister was quick to dispose of boyfriends, so he made a point of being at the Robinson family home at 7436 South Euclid Avenue to meet this newest suitor.

Craig and Michelle’s parents, Fraser and Marian Robinson, were, like their children, lifelong residents of Chicago’s South Side. Both high school graduates, they had married in October 1960, but Fraser’s hope of finishing college was dashed by insufficient funds. In January 1964, just a few days before Michelle’s birth, Fraser was hired by the city water department, and Marian became a stay-at-home mom. In 1965 the young family moved from the Parkway Gardens Homes in Woodlawn to the cramped top floor of Marian’s aunt’s home on Euclid Avenue, in solidly middle-class South Shore. Craig and Michelle attended nearby Bryn Mawr Elementary School, where Craig skipped third grade and Michelle skipped second. Separate small bedrooms and a common study area gave them their own modest spaces at home. At work, tending steam boilers, Fraser won two promotions along with salary increases, but an increasingly dark cloud hung silently over the happy young family: at age thirty, Fraser had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, though, as Craig later wrote, “we never had an in-depth discussion at home about the frightening course that MS was known to take.” In time, Fraser needed to use a cane and then crutches to help him walk, but he stuck with his job. “We saw him struggle to get up and go to work,” Michelle recalled. “He didn’t complain—ever. He put his energy into us.”

When Michelle reached ninth grade and was admitted to Whitney Young High School, west of downtown, she spent hours a day riding city buses to and from school. Craig won admission to Princeton in 1979, and his father insisted the family would make the necessary financial sacrifices for Craig to go there rather than accept a full scholarship from some less prestigious institution. Michelle grew up thinking she was smarter than her brother, and although Craig had a difficult freshman year, Michelle resolved that if he could attend Princeton, so could she. Her mother knew that test taking was not her forte, and a high school counselor discouraged her interest in Princeton, but Michelle applied anyway and was admitted. The difference between the South Shore world from which Michelle came and the privileged backgrounds of Princeton’s overwhelmingly white and often wealthy student body was profoundly stark.

“The first time when I set foot in Princeton, when I first got in, I thought ‘There’s no way I can compete with these kids … I got in but I’m not supposed to be here,’ ” Michelle recalled. “I remember being shocked by college students who drove BMWs. I didn’t even know parents who drove BMWs.” In addition, black undergraduates realized that Princeton’s racial climate, even in 1981, left much to be desired. Angela Kennedy, one of Michelle’s closest friends, with whom she spent one summer working as counselors at a girls’ camp in New York’s Catskill Mountains, recalled that “It was a very sexist, segregated place. Things reminded you every single second that you’re black, you’re black, you’re black.”

Michelle thrived in Princeton’s classrooms, and by the beginning of her senior year, she was applying to Harvard Law School. Yet in a reprise of high school, her faculty adviser on her senior thesis downplayed her chances. After initially being wait-listed, in late spring of 1985 she was accepted to Harvard.

Michelle’s college thesis, “Princeton-Educated Blacks and the Black Community,” was a powerfully self-revealing document. “My experiences at Princeton have made me far more aware of my ‘Blackness’ than ever before,” Michelle wrote. “I have found that at Princeton … I sometimes feel like a visitor on campus; as if I really don’t belong.” Growing up in South Shore, neither of her parents had been especially outspoken about race, but Marian Robinson’s father Purnell “Southside” Shields, who died in 1983, “was a very angry man,” Michelle’s mother explained. “I had a father who could be very angry about race,” and Marian had given Craig the middle name Malcolm after the early 1960s’ angriest racial firebrand. Marian was likewise wary of interracial relationships. “I worry about races mixing because of the difficulty,” she confessed years later. “It’s just very hard.”

But Princeton made Michelle understand that “I’m as black as it gets.” In her thesis, she observed that “with Whites at Princeton, it often seems as if, to them, I will always be Black first and a student second.” Looking ahead, that left her fearful. “The path I have chosen to follow by attending Princeton will likely lead to my further integration and/or assimilation in a White cultural and social structure that will only allow me to remain on the periphery of society; never becoming a full participant.” She confessed that “my goals after Princeton are not as clear as before” and she rued how “the University does not often meet the social and academic needs of its Black population.” In addition, “unfortunately there are very few adequate support groups which provide some form of guidance and counsel for Black students having difficulty making the transition from their home environments to Princeton’s environment,” as both Michelle and her brother had. She now knew that Princeton was “infamous for being racially the most conservative of the Ivy League Universities.” And her exposure to some fellow students had taught her something else, something prescient indeed: “a Black individual may be unable to understand or appreciate the Black culture because that individual was not raised in that culture, yet still be able to identify as being a Black person.”

Harvard Law School did not offer a much different experience. Czerny Brasuell, Michelle’s one black female Princeton mentor, recounted Michelle telling her by telephone from Cambridge that “If I could do this over, I’m not sure that I would.” A female classmate told Michelle’s biographer Liza Mundy that Harvard “was not a friendly, happy atmosphere.” But once again Michelle persevered. After her 1L year, she returned to Chicago as a summer associate at the law firm of Chadwell & Kayser, working for female partner Jan Anne Dubin and staying with her parents in the home that her great-aunt had deeded to the Robinsons several years earlier, prior to her own death.

Back at Harvard for her 2L year, Michelle volunteered significant time at the Legal Aid Bureau, located one floor—and many status rungs—below the Harvard Law Review on Gannett House’s ground level. After her 2L year, she was a summer associate at Sidley & Austin’s Chicago office. When Sidley offered her a position once she graduated, Michelle readily accepted. At Harvard, “the plan was you go into a corporate firm. So that’s what I did. And there I was. All of a sudden, I was on this path.”

At graduation, her parents paid for a teasingly congratulatory message in the 1988 Harvard Law School Yearbook: “We knew you would do this fifteen years ago when we could never make you shut up.” That summer, Sidley paid for the bar review class she took alongside a friend of her brother’s, Alan King, but only on May 12, 1989—after taking the Illinois exam a second time—did Michelle become a member of the Illinois Bar. Working in Sidley’s intellectual property group, Michelle yearned for meaningful assignments. Given her Harvard loans, her Sidley salary was attractive, but she had not really intended to be a corporate lawyer. “I hadn’t really thought about how I got there,” she recalled. “It was just sort of what you did.”

Craig Robinson recalled the late July evening when Michelle introduced Barack to her family. “My sister brought him over to my mom and dad’s house. We all met him, had dinner. They left to go to the movie, and my mom and dad and I were talking: ‘Oh, what a nice guy. This is going to be great. Wonder how long he will last?’ ” Craig thought Barack was “smart, easygoing, good sense of humor,” but given Michelle’s proclivity for discarding boyfriends, Craig remembered thinking, “Too bad he won’t be around for long.” Marian Robinson was also impressed because “He didn’t talk about himself,” but instead drew out the Robinsons about their own lives and interests. “I didn’t know his mother was white for a long time,” Marian recalled. “It didn’t come up.”

Barack’s taste in movies ran to the realistic, and opening that weekend was Leola, the story of a bright seventeen-year-old African American Chicago girl whose desire to attend college was endangered when she became pregnant. Filmmaker Ruby Oliver was a fifty-year-old former day care operator, and seven weeks after they saw it, Barack talked about the ninety-five-minute movie—later retitled Love Your Mama—while addressing the real-life challenges confronted by black youths. Michelle and Barack continued to see each other almost every day, and when they went out, Michelle usually paid. “He had no money; he was really broke,” she remembered, plus “his wardrobe was kind of cruddy.” Barack’s Occidental roommate Paul Carpenter was visiting Chicago that August, and he heard about Michelle when the two old friends and Paul’s wife Beth had dinner one evening. Another night, Craig and his wife Janis dropped off Michelle at Barack’s sublet in Hyde Park, and Janis and Barack recognized each other from their time at Columbia. “He came out of his apartment to get Michelle, then he and I both said, ‘Oh my gosh, I remember you,’ ” Janis recounted.

Before Barack’s return to Cambridge, Michelle told Craig, “I really like this guy” and made a request. She had heard her father and Craig say that “you can tell a lot about a personality on the court,” something Craig had learned from Pete Carril, his college coach at Princeton. Michelle knew that Craig played basketball regularly at courts around Hyde Park, and he remembers her asking: “I want you to take him to play, to see what type of guy he is when he’s not around me.” Craig agreed to take on this task, but he recalled, “I was nervous because I had already met Barack a few times and liked him a lot.”

Craig quickly scheduled a meet-up, and they played “a hard five-on-five” for more than an hour. Craig’s nervousness quickly fell away because he could see that Barack was “very team oriented, very unselfish,” and “was aggressive without being a jerk.” Craig was happy he could “report back to my sister that this guy is first rate,” and Michelle was pleased. “It was good to hear directly from my brother that he was solid, and he was real, and he was confident, confident but not arrogant, and a team player.” Craig saw only one huge flaw in Barack’s skill set, but it was not relevant to Michelle’s question. “Barack is a left-handed player who can only go to his left.”

Before Obama headed back to Cambridge in mid-August, he knew that this new, two-month-old relationship with Michelle Robinson was perhaps on a par with his now-truncated, three-year-old involvement with Sheila. For Barack, the differences were huge. Sheila was also the biracial offspring of international parents; she had lived in Paris, spoke French and now Korean, and was comfortable around the globe—just like Australian-born, Indonesian-reared diplomat’s daughter Genevieve Cook before her. Michelle Robinson was a graduate of Princeton and Harvard Law School, but she was a 100 percent product of Chicago’s African American South Side, just like so many of the women and men who had revolutionized Barack’s understanding of himself during his transformative years in Roseland.

Barack’s prior relationships had been with women who, like himself through 1985, were citizens of the world as much as they were of any particular country or city. Before Princeton, Michelle Robinson had spent one week each summer with her family at Dukes Happy Holiday Resort, an African American forest lodge in White Cloud, Michigan, forty miles north of Grand Rapids. But if Barack truly believed that his destiny entailed what he thought, he knew full well the value of having roots in one place and having that place be essential to your journey. And who more than Michelle Robinson and her family could personify the strong, deep roots of black Chicago?

Although Michelle would not know that Barack had shared his deeply private sense of destiny first with Sheila and then with Lena, before he left for Cambridge, Barack told Michelle about his belief about his future role. “He sincerely felt, from day one that I’ve known him, that he has an obligation,” Michelle explained, “because he has the talent, he has the passion and he has been blessed.”

The Harvard Law Review, founded in 1887, was in 1989 the oldest and most prestigious legal publication in the United States. Edited entirely by students—beginning with thirty-eight from the rising 2L class, supplemented each successive summer by several top-GPA 3L “grade-ons” for an annual total of about forty—the Review published eight hefty issues a year—November through June—with the law students contributing twenty to forty or more hours of work weekly, aided by a trio of female office staffers and a quintet of part-time undergraduate work-study students. Beyond the law students, there was an oversight board of two professors, the dean, and an alumnus, but they played only a nominal role. In addition, playing an obtrusive role in the Review’s life was eighty-five-year-old eminence grise Erwin N. Griswold, the law school’s dean from 1946 to 1967 (and himself the Review’s top officer—president—in 1927–28), who critiqued every issue and was available to hector the student editors.

The mid-August return to Cambridge served two long traditions. One was to initiate the new 2L editors into the sometimes-complex internal workings of the Review. The masthead—the president, treasurer, managing editor, supervising editors (SEs), and executive editors (EEs)—oversaw the work of five “offices”: Articles, which reviewed scores of long manuscripts submitted by law professors nationwide and chose a dozen or so per year for publication; Notes, which selected and edited substantive analyses written by the HLR editors themselves; Book Reviews and Commentaries, which assigned and handled shorter pieces; “Devo,” or Developments in the Law, which prepared a major team-written study of some cutting-edge topic for publication in each year’s May issue; and Supreme Court, which oversaw the annual November issue and its several dozen student-written synopses of significant cases decided during the prior term of the U.S. Supreme Court. The November issue also contained the Review’s two top-status faculty contributions: the foreword, written every year since 1951 by an emerging star chosen by the editors, and a major case comment authored by an eminent academic, a feature added in 1985.

In HLR’s very elaborate editing system, overseen by the managing editor, student-written work moved from the offices to the SEs and then the EEs; faculty pieces went directly from the offices to the EEs. Everything also went through a “P-read,” in which the Review’s president recommended editorial changes. Each fall and winter “the 2Ls are the labor, the 3Ls are the management,” 2L editor Brad Berenson recounted, until a new masthead for the upcoming year was chosen from among the 2Ls early in February.

The second reason for the pre-semester start was that the November issue had to go to the printer by mid-October. The 2Ls needed an intensive refresher course in Bluebook legal citation style, followed by an introduction to two other common tasks: sub-citing, in which the accuracy of every quotation and footnoted reference in each piece was confirmed by checking the original source, and roto-pool, in which every faculty-submitted manuscript was read and evaluated by several editors before full consideration by the Articles Office.

Most 2Ls spent their first HLR semester in “the pool,” where almost every weekday morning a pink slip of paper from managing editor Scott Collins would appear in their pigeonhole mailbox in the editors’ lounge on the second floor of Gannett House, telling them what their work assignment was. Editors were enticed there each morning by a spread of free muffins and bagels. “My chocolate chip muffin was the mainstay of my morning,” 3L editor Diane Ring recalled. Thanks to the hefty income the Review received from sales of The Bluebook, free pastries seemed like “a very interesting strategy to make sure you got all those second-years on the doorstep every morning getting their assignment, doing the work,” Ring explained. Patrick O’Brien, also a 3L, remembered that “a lot of my law review involvement had to do with free bagels and cream cheese. It would get me there every morning for a free breakfast.” There also were free evening snacks for those who worked late, and as a result, Berenson recalled, Gannett House became “a gathering place,” “almost like a fraternity house for the editors.” Marisa Chun, a 2L, explained that the editors’ lounge and its television served as “our living room.” With everyone’s classes in nearby buildings, popping in and out was a constant feature of HLR life. For some editors, Gannett House became the center of their daily lives, while for others, especially those who were already married, the Review was more like a demanding part-time job.

The 2Ls had three ways out of the “hideous experience” of doing pool work: join the five-person “Devo” team, whose work would satisfy the law school’s written work requirement; join a multiperson group assigned to edit an especially difficult article; or write a note of one’s own, an option often postponed until the 3L year and almost always done for independent study credit under faculty supervision. Gordon Whitman, the 3L Articles Office cochair, had worked for a year as a community organizer in Philadelphia before starting law school and had successfully pushed for the acceptance of a manuscript that argued that the real-world theology of Martin Luther King Jr. offered a superior perspective for examining the contentions made by “critical legal studies” scholars.

The article’s author, Anthony E. Cook, was an African American associate professor of law at the University of Florida who had graduated magna cum laude from Princeton before getting his law degree at Yale. Cook’s dense and complicated analysis looked especially daunting, and Whitman recruited four new 2L editors to work on it: Christine Lee, the young Oberlin graduate who was just about to turn twenty-two, the now twenty-eight-year-old Barack Obama, whom Lee had disliked from their first introduction a year earlier, and two other visibly sharp 2Ls, Susan Freiwald, a 1987 magna cum laude graduate of Harvard College, and John Parry, a 1986 summa cum laude graduate of Princeton. The lengthy manuscript would require weeks of work—it was not scheduled for publication until the March issue—and these four knew by early September what their fall work for the Review would entail.

Fall semester classes began on September 6. Barack and Rob had carefully debated their choices. In Laurence Tribe’s huge and oversubscribed Constitutional Law section, which met five hours per week, they were joined by a number of their 1L Section III classmates. The assigned casebook, William B. Lockhart et al.’s Constitutional Law: Cases and Materials, 6th ed., was the best available. Word among students was that African American professor Christopher Edley, who was back after serving as issues director for Michael Dukakis’s presidential campaign, was “refreshingly good.” His class, Administrative Law, might sound dry and arcane, but Edley taught the sixty-five-student, four-hour-a-week class as an entirely practical “this is how the public policy process works” course, and he supplemented the main text, Walter Gellhorn et al.’s Administrative Law, 8th ed., with various other materials.

Rob and Barack had “an extended discussion” about taking Corporations, as most 2Ls did, weighing the upside value of “understanding the world” versus how their grades in the four-credit class might harm their goal of graduating magna cum laude. But they began it and kept it, finding that Professor Reinier Kraakman, a Yale law graduate with a Harvard sociology Ph.D., “had an interesting mind and approach.” Kraakman focused on “the control of managers in publicly held corporations” and emphasized “the functional analysis of legal rules as one set of constraints on corporate actors.” Rob and Barack found it “a good class, really cool,” and “really enjoyed it.”