По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

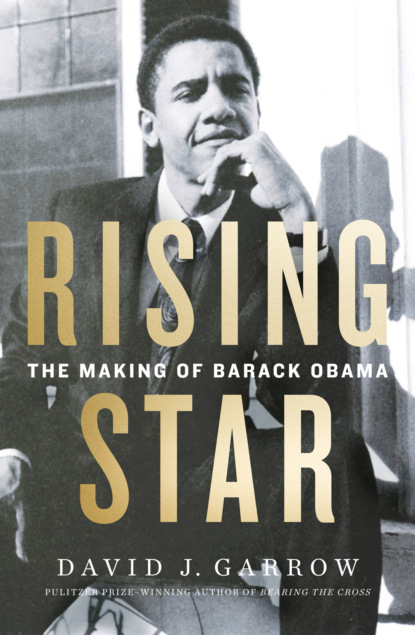

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Barack’s diminution of his life with Sheila to Lena was reminiscent of how he had characterized it to Phil Boerner eighteen months earlier: “winter’s fast approaching, and it is nice to have someone to come home to,” given his “mortal fear of Chicago winters.” After years of distancing himself from his mother, Barack’s identification as African American—not international, not hapa, not biracial—was now complete. This transformation had been immensely aided by his exposure to and ease with strong black women like Loretta Augustine, Marlene Dillard, Aletha Strong Gibson, and Yvonne Lloyd, but this success came at a high price, one visible only in the light of the distance, the unknowable distance, that was always impenetrably there. That distance, that lightness, would extend well beyond 1988.

Two days after the action against Jim Fitch, a remarkable, substantive victory was announced by attorney Tom Geoghegan: Navistar, the renamed International Harvester, would pay $14.8 million to Frank Lumpkin and twenty-seven hundred other surviving former Wisconsin steelworkers. The largest individual payment would be $17,200, though Frank, with a better-protected pension, would receive only $4,000.

No one in Chicago doubted that Frank deserved the most credit for this achievement, and the ex-workers approved the settlement in an overwhelming vote of 583 to 75. But Frank was never someone to pat himself on the back. “It is a victory of sorts,” he told the Daily Cal. “It was the best we could get, and that’s the way everyone who voted for it felt. But we appreciate the feeling that the little guy has won and that giants can fall.” Tribune business editor Richard Longworth wrote a wonderful tribute to Frank, describing him as “an amazing man … who is probably as close to a saint as Chicago has these days.” Tom Geoghegan is “the only other real hero,” a commendation underscored when James B. Moran, the federal judge handling the Wisconsin litigation, publicly praised Tom’s “dedication,” “professionalism,” and “modesty in seeking fees.” Frank also represented the last of a dying breed: at South Works hardly seven hundred men were still working, and Republic LTV was down to 640. Maury Richards would soon be reelected as Local 1033’s president, but even as dedicated a steelworker as Maury was beginning to wonder what his next career would be.

By mid-February, UNO, hoping to take the lead in Chicago’s fractured school reform movement, distributed a twenty-nine-page proposal to compete with a much more detailed plan championed by Don Moore’s Designs for Change, Sokoni Karanja, and Al Raby from Haymarket. DCP was listed as an organizational backer of UNO’s plan, but no DCP member was among the twelve names credited with preparing the document. Danny Solis, Peter Martinez, and Lourdes Monteagudo, an elementary school principal now working closely with UNO, were among them, as was an education professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Bill Ayers, who had arrived there six months earlier and met both Danny and Anne Hallett the previous fall. Acknowledging that “good schooling is an expensive proposition,” the UNO proposal called for the hiring of an astonishing 14,563 additional educators for Chicago’s elementary schools, at a cost of $442 million. UNO envisioned an annual CPS budget increase of $584 million, and called for a $481 million increase in state funding to support it.

On February 18, the same day that the Sun-Times gave the proposal prominent coverage, UNO and DCP brought busloads of members to a school reform hearing at board of education headquarters, but the overflow crowd intimidated officials and the meeting was adjourned. Soon a third major plan, this one backed by Fred Hess’s Chicago Panel, Gwendolyn LaRoche from the Chicago Urban League, and Patrick Keleher from Chicago United, joined the confusing fray. DCP concentrated on getting its Career Education Network off the ground, with Obama and Owens hiring an African American woman in her early thirties, Cassandra Lowe, who had been working as a college recruiter for nearby St. Xavier University, to oversee it. By early March, afternoon counseling sessions for fifty or so high school students were finally under way at Reformation Lutheran and at Our Lady of the Gardens. Asked about DCP’s 1987–88 change from an employment emphasis to its new concentration on secondary schooling, Owens explained that “the focus shifted to the more fundamental question of preparing people for jobs in a changing society.”

By the end of February, Barack had to decide both about law school and about making his long-mulled trip to Kenya before the fall 1988 academic year began. His sister Auma had returned home from Heidelberg and would eagerly host a midsummer visit.

Barack later would write that he applied to Harvard, Yale, and Stanford, but he also applied elsewhere, including to Northwestern University’s law school, right in downtown Chicago. Acceptance letters had arrived from both Harvard and Northwestern, but with one huge difference: Harvard’s financial aid package would require him to take out loans of well over $10,000 a year, while Northwestern’s offer, the Ronald E. Kennedy Scholarship, would allow him to attend a top-twenty law school in Chicago for free. Debating his choice of school, Barack asked Jean Rudd and Ken Rolling at the Woods Fund about attorneys from whom he could seek advice. Jean’s husband Lionel Bolin was a descendent of a famous African American family, a 1948 graduate and now a trustee of prestigious Williams College, and a successful broadcast executive who, after serving in the U.S. military, had graduated from low-cost New York Law School. Woods Fund board member George Kelm, a low-key civic activist, had been managing partner of a prominent Chicago law firm, Hopkins and Sutter, before becoming president of the Woods family’s Sahara Enterprises investment firm.

Barack “was trying to make a strategic choice about which school,” Jean Rudd recalled, and Jean and Ken remember Barack telling them about Northwestern’s full-scholarship offer. George Kelm was a Northwestern Law School alumnus and a past president of its alumni association, and he strongly advised Barack against attending Harvard. Northwestern was so interested in persuading Barack to accept its Kennedy Scholarship, named after an African American faculty member who had died four years earlier at the age of forty-two, that the admissions office asked the law school’s dean, Robert W. Bennett, to speak with Obama. “The admissions people came to me and they said, ‘We’ve got a fantastic prospect for this scholarship’ ” and “ ‘we want you to try to talk him into taking it,’ ” Bennett recounted. “Barack was brought to my office” and “I tried to talk him into taking this Ronald Kennedy Scholarship.” Bennett was a 1965 cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School, and Barack was “the only applicant that the admissions people ever” asked him to help recruit during a full decade as dean.

Neither Kelm and Bennett’s efforts nor the full three-year scholarship were sufficient to outweigh Barack’s belief in his destiny. Harold Washington had graduated from Northwestern’s law school, and only once had a Harvard law graduate become president—Rutherford B. Hayes, in 1877. Northwestern law alumni had been major party presidential nominees five times, but William Jennings Bryan was a three-time loser and Adlai Stevenson had lost twice. It would be a costly decision for Barack—a cumulative difference of more than $40,000—but his choice was evidence of how deeply he believed what he so far had shared only with Sheila and Lena.

The only person in Barack’s workday world, other than Lena, to whom he spoke about leaving was Johnnie Owens, whom he had recruited to DCP with at least half an eye toward this decision. Johnnie remembered the moment clearly. “I didn’t have a clue until one day he asked me, ‘Are you ready to lead?’ I’m like ‘What do you mean? What are you talking about?’ ‘I’ve been accepted at Harvard Law School,’ ” and he would be leaving DCP to attend its three-year J.D. program. “And I’m like ‘What?’ ” Owens remembered, for there had been no prior indications that Barack was contemplating such a future. “Nothing. Absolutely nothing: about applying, that he was interested, anything like that. And so he began explaining to me how he’d been struggling with the thought of maybe going into the ministry versus law school.” Neither Sheila nor Lena ever heard him talk about the ministry, but as Johnnie remembers it, Barack “said he had ideas and thoughts about going into the ministry and that he had actually talked to Reverend Wright about some of this.”

Barack asked Johnnie to succeed him as DCP’s executive director, promising not only to work with the members on the transition, but also to introduce Owens to the trio of women who were DCP’s most important funders: Jean Rudd at Woods, Aurie Pennick at MacArthur, and Anne Hallett at Wieboldt. Owens agreed, but several weeks passed before Barack was ready to tell DCP’s volunteer leaders about his upcoming move.

On March 5, ten days before Democratic ward-level and congressional primary elections across Chicagoland, the Chicago Tribune reported that Waste Management had fired two managers at its SCA chemical waste incinerator at 11700 South Stony Island Avenue for repeatedly disconnecting air-monitoring devices designed to measure the facility’s destruction of highly toxic PCBs. WMI insisted that the misconduct “did not threaten health or safety,” but Marian Byrnes, Hazel Johnson, and congressional candidate Mel Reynolds picketed the plant, demanding it be closed. Metropolitan Sanitary District officials pulled back from a plan to dump eighty thousand cubic yards of sewage sludge in a wetlands property five blocks south of SCA.

Howard Stanback, Bruce Orenstein, and Barack were working on plans to have Mayor Sawyer attend a postelection March 17 rally at St. Kevin to announce publicly the city’s strategic alliance with UNO and DCP regarding landfills. On Election Day, four African American ward committeemen who were allied with Sawyer were defeated, an unsurprising verdict on the process that had made Sawyer Harold Washington’s successor. Two successful challengers were forty-eight-year-old educator Alice Palmer in the 7th Ward, who defeated organization loyalist William Beavers in a virtual landslide, and young West Side activist Rickey Hendon in the 27th Ward. Another winner, in a South Side state representative contest, was 8th Ward precinct captain Donne Trotter, who a year earlier had turned out such an impressive victory margin for Harold Washington at London Towne Homes. One of the few challenges to a Sawyer loyalist that failed was Salim Al Nurridin’s 9th Ward committeeman contest against Bill Shaw, whose twin brother Bob, the 9th Ward alderman, bizarrely alleged that Salim operated a harem full of welfare recipients. Only slightly more uplifting had been Emil Jones and Mel Reynolds’s unsuccessful challenges to incumbent 2nd District congressman Gus Savage.

When the Tribune reported that the thirty-six-year-old Reynolds had voted only twice since he turned twenty-one, Reynolds claimed that plotters had altered his voting records. Tribune political reporter R. Bruce Dold commended Reynolds for running “a surprisingly effective first-time campaign” and praised him as “a walking role model for black achievement.” But when the votes were tallied, Reynolds received only 14 percent, Jones 24 percent, and Savage won renomination with just 53 percent.

Stanback, Orenstein, and Obama carefully scripted the St. Kevin evening rally where Gene Sawyer would eagerly agree to UNO and DCP’s demand for a new mayoral task force to study the city’s landfill options. Unlike Jim Fitch’s committee, this new group would be heavily stacked with UNO and DCP loyalists. Howard, Bruce, and Barack jointly drafted Sawyer’s remarks, and then both organizers, along with Lena and Loretta, met with Sawyer, Stanback, and other mayoral aides at City Hall. A young assistant to Stanback, Judy Byrd, remembered being struck by Barack, who “spoke with such command and such clarity.” This was in stark contrast with Bruce’s impression of the new mayor. “I remember in that meeting talking to Sawyer,” Orenstein said, “and feeling like no one’s there, no one’s home.” Yet the central trio worked exceedingly well together. Bruce found Barack “very collaborative and very easy to work with,” and was repeatedly impressed by how Barack made sure that his top leader was never ignored or left out: “he was looking out for Loretta.” In addition, “Stanback’s a full partner. I remember Stanback saying at the time that he’s never had a more collaborative relationship with a community organization, and he really appreciated it.”

At Stanback’s insistent urging, Orenstein also tried to convince some hard-core landfill opponents like Marian Byrnes to take part in the new process, but Byrnes realized that this was all leading to two predetermined ends: a new landfill at O’Brien Locks that the city desperately needed, and a $20 to $25 million community trust funded by Waste Management that would be controlled by UNO and DCP, not Jim Fitch and the wider community.

Angry but determined, Marian, Hazel Johnson, and others picketed St. Kevin that evening, distributing a no-more-landfills flyer that invoked the title and featured song from the Eyes on the Prize civil rights documentary that had aired a year earlier. UNO members tried to obstruct the leafleting, and when Hegewisch News editor Vi Czachorski, a UNO opponent, tried to enter the basement, UNO’s Phil Mullins physically blocked her. “As I descended St. Kevin’s stairs, Mullins put his arms across the narrow stairway and said ‘You can’t attend this meeting.’ I tried to continue, crowds pushed. Mullins said ‘I’m getting the police. I’ll charge assault!’ ” Czachorski wrote in the next issue of her weekly newspaper. “I left.”

UNO and DCP’s own dueling flyer demanded that Sawyer name a new task force “made up entirely of residents who live in communities affected by landfills.” Only such a group can “take this issue out of the backrooms and into the light of day.” DCP also distributed a statement in Loretta Augustine’s name denouncing “backroom deals that ram landfills down the communities’ throats and send the enormous profits from such dumping into corporate and city coffers.”

As a crowd of more than six hundred filled St. Kevin’s basement, Orenstein paced nervously while Barack was “relaxed and cool.” Sawyer carried with him a briefing memo summarizing the remarks that Loretta and Mary Ellen would make as well as his own speech, typed out in large, bold capital letters. A seven-piece mariachi band provided entertainment as multiple TV camera crews set up their equipment. DCP president Dan Lee and St. Kevin pastor George Schopp joined Loretta, Lena, and the mayor on the stage.

DCP’s Loretta Augustine opened the meeting. “We, as residents, have had no control over what has happened in our community. We are tired of being victims. We are taking control of our own community.” Then Lena spoke, followed by Sawyer. “Waste disposal and landfill decisions will no longer be made in the back room, at a table full of politically connected financial opportunists,” the mayor read, his text sounding far more like Bruce Orenstein than Gene Sawyer. “Whatever happens here will be because you decide.”

With Lena and Loretta flanking the mayor, Lena then took charge of the traditional IAF-style colloquy with Sawyer, just as she had with Harold Washington almost five years earlier on that same stage. UNO and DCP had encouraged their supporters to be boisterous, and one reporter called the crowd “raucous.” Lena enjoyed her role to the hilt, and she began reciting the formal demand that the mayor appoint a new task force within ten days. She warned Sawyer to “be careful how you respond because this is an angry group of people tonight.” The mayor stuck to his script and pledged full acceptance of UNO and DCP’s demands. At that point, Lena turned to the cheering crowd and declared, “I’m going to take it for granted that we will have all the power we want!” As one veteran organizer later remarked, five years as a quintessential Alinsky leader had made Mary Ellen Montes into “one of the most macho women I had ever met.”

As the gathering concluded, Bruce and Barack were ecstatic about the meeting. But UNO and DCP’s Alinsky-style power grabs—first blowing up the Fitch talks, then bringing a sad sack mayor to heel before an excited crowd—had fractured the Southeast Side community. Bruce, Lena, and Barack had succeeded in infuriating and alienating the local business leadership and the true environmentalists, two groups that just weeks earlier had been prepared to join forces in a true community consensus. Ed Vrdolyak quickly put Sawyer on notice, objecting to the city allowing UNO and DCP to control negotiations with Waste Management: “For certain community organizations who without question do not truly represent the vast majority of homeowners, residents, and taxpayers to submit their community buyout (sellout) wish list is totally and completely wrong.”

But Vrdolyak’s public protest bore no political fruit, and a week later, Sawyer and Stanback announced a new sixteen-member Task Force on Landfill Options: Mary Ellen Montes led a group of five UNO supporters, including Father George Schopp; five other appointees were DCP members: Loretta Augustine, Dan Lee, Marlene Dillard, Margaret Bagby, and Father Dominic Carmon. Bob Klonowski was another ally, and no more than three appointees, including Marian Byrnes and Hazel Johnson, were likely dissenters. It was hard to imagine a more politically unrepresentative group.

In late March Barack announced his upcoming departure. He went to see Loretta first. “He told me he was leaving and he needed to go back to school.” Most DCP members learned the news at a meeting where Barack spoke of a smooth transition to Johnnie Owens as his successor. Dan Lee recalls that “I wanted to cry” and “we all got teary-eyed…. He was like a brother.” Tommy West called out, “No, you can’t go,” but they all realized that Barack’s potential reached well beyond Roseland. “We hated to see him go,” Yvonne Lloyd remembered. “It was very sad,” but they all appreciated, as Betty Garrett explained, that “if he could better himself, then we wanted him to go.” Barack remembered overhearing Yvonne remark how different he seemed now than he did on that August day two and a half years earlier when Jerry Kellman had first introduced him. “He was just a boy. I swear, you look at him now, you’d think he was a different person.” Of course, in many ways indeed he was.

Cathy Askew was the most emotional about Barack’s announcement. “I was really upset,” she recalled. “I thought we were friends.” Barack remembered Cathy expressing her disappointment and saying. “What is it with you men? Why is it you’re always in a hurry? Why is it that what you have isn’t good enough?” Yet they all understood how frustrating the past year had been for Barack. “For the leader or organizer who feels expected to bring some change and improvements to the community, the day-to-day litany of roadblocks and resistances makes it hard,” one close observer of Chicago organizing wrote that spring.

Marlene Dillard had watched Barack experience repeated setbacks while always trying to hide his disappointment from DCP’s members. The outreach to Local 1033 at Republic LTV had gone for naught, the efforts in Altgeld Gardens had led to little, and only now was a tiny version of CEN getting under way. Again and again, “I always felt that it was a disappointment to him.” Whenever she and Barack visited a funder like Woods, “he was trying to project how great we were doing.” Then, “when we were leaving,” he would turn to her and apologize for his braggadocio: “Well, we’re trying.” Overall, “I think it weighed very heavy on him…. He was leading people, and he was getting nowhere.” Indeed, Marlene came to believe “that he felt ‘If I could just become the mayor of Chicago, I would be able to do this.’ ”

Ernie Powell saw the same thing. “I think Barack got a little frustrated with that, and he felt like he had to get into the seat of power.” The DCP pastors who interacted regularly with Barack understood likewise. With CEN operating out of Reformation Lutheran, Tyrone Partee saw Barack almost daily and remembered him saying, “I’m going to law school.” Barack knew Tyrone was from a political family, and to him, Barack was “clear that he wanted to go into politics. ‘I believe that’s what I’m called to do.’ ” Alvin Love was caught off guard by Barack’s announcement, but he realized Barack was “frustrated with the speed of change” and had concluded that “there might be a better way to do” things.

Barack went to see both Rev. Eddie Knox at Pullman Presbyterian Church and Rev. Rick Williams at Pullman Christian Reformed Church in person. With Knox, Barack presented Harvard as an opportunity he was pondering, and Knox smilingly replied, “There isn’t much to think about.” Harvard was such “a golden opportunity” and Knox believed “You’re going to go far.” Rick Williams reacted similarly. “I’m happy for you,” Rick remembered saying, “but I’m also sad, because this kind of work needs people for the long haul, people like yourself.” Rick understood Barack’s hope of building a truly large, multicongregational alliance to pursue educational reform and employment opportunity all across Chicago, but, just as Jeremiah Wright had sought to explain a year earlier, bringing people and churches together behind such an agenda was far more complicated than Barack could imagine. Rick told Barack that Harvard was “a wise decision” and wished him well. “You are going to do more for more people getting a law degree from Harvard than you would do here.” Barack had “a passion for making life better for lots of people,” Rick remembered, and to do that, “you’ve got to have power.”

Barack also visited Emil Jones at his office on 111th Street. No elected official had done more for Barack and DCP, and Jones said he was sorry to see him go. To Jones as to others, Barack emphasized that there was no question he would return to Chicago after law school. He called Renee Brereton and other CHD staffers to tell them, plus organizing colleagues like Linda Randle. Barack apologized to Howard Stanback for pulling up stakes during their landfill effort. Stanback was surprised by Barack’s choice. “ ‘Why are you going to Harvard?’ He said, ‘Because I need to.’ I said, ‘Are you coming back?’ ” to which Obama said, “I’m absolutely coming back.”

Barack, Loretta, and Yvonne Lloyd all attended Lena’s thirtieth birthday party, but by early April, there was not much to celebrate regarding UNO and DCP’s position in the Southeast Side’s landfill war. Anger at Sawyer’s new task force was white hot, especially in Hegewisch, just across the Calumet River from the O’Brien Locks site. Hegewisch News editor Vi Czachorski asked Howard Stanback, “Why should UNO decide if there will be a landfill in our backyard?” and Marian Byrnes, Hazel Johnson, and three allies called the task force unrepresentative and called on Mayor Sawyer to disband it. That group held its first public hearing at St. Kevin on April 7, and this time UNO’s critics made it into the basement meeting room, mocking cochairwomen Lena Montes and Loretta Augustine with chants of “No deals,” the same slogan Lena had used during the Fitch ambush two months earlier.

The Daily Cal reported that Loretta defended the panel’s “makeup and goals” as a “positive development for the community and said the mayor had pledged to abide by the task force’s findings,” with its report due at the end of May. “The panel approved reopening discussions with Waste Management,” with Lena declaring, “What is different about it is that it will be talked about in open hearings, not behind closed doors.” But when old foe Foster Milhouse rose to speak, “Montes quickly closed” the meeting.

The Daily Calumet editorialized against any reopening of negotiations with WMI, and UNO’s opponents advocated for a popular referendum vote against landfill expansion on the upcoming fall general election ballot in Southeast Side wards. One week later, the task force convened its second hearing at Our Lady of the Gardens gymnasium in Altgeld Gardens, where the tumultous Zirl Smith meeting had occurred two years earlier. Father Dominic Carmon, a task force member and Our Lady’s pastor, remembered that Barack “was there listening,” as at the previous St. Kevin session too. Howard Stanback, Jim Fitch, and WMI’s Mary Ryan all spoke to the panel as a crowd of 125 chanted “No more dumps.” For the first time, Stanback publicly acknowledged that the city did want the O’Brien Locks site to become a new landfill. Mary Ryan said WMI would immediately place $2 million into a community trust fund, with similar sums to be added every year, and it would give up title to two other parcels of land, including the marshland just below South Deering whose vulnerability had led Harold Washington to impose the initial landfill moratorium. That was followed by numerous single community members who spoke fervently against the deal. In the days that followed, the Daily Cal kept up a regular drumbeat against the task force. “Why study something no one in the community wants or asked for?” political columnist Phil Kadner queried.

As the UNO–DCP landfill gambit drew more and more flak, the task force’s third hearing, scheduled to take place at Bob Klonowski’s Hegewisch church, was postponed and moved to Mann Park’s field house. When it finally convened, Klonowski welcomed the crowd in a calm tone, but, according to Vi Czachorksi, when a city representative again explained why O’Brien Locks was the best option available, “500 angry, frustrated people shouted down the city proposal of a new landfill.” The meeting “ended abruptly when Mary Ellen Montes lost control, stating ‘This has turned into a war.’ ” Declaring that “It doesn’t appear we can conduct this in a civilized manner,” she dissolved the hearing, leaving the entire UNO–DCP–Stanback strategy in tatters. The mayor’s office named several additional task force members and postponed its reporting date until later in the summer, but the entire venture was now dead.

Years later, Bruce Orenstein acknowledged that his and Barack’s game plan had gone entirely awry. When “we make ourselves the center of authority … we make ourselves the target” for large numbers of Southeast Side residents who for years had been opposed to the city using their neighborhoods as a dumping ground. Orenstein mused that if Harold Washington had not died, perhaps the O’Brien Locks deal with Waste Management could indeed have netted the community a $25 million trust fund, just as he, Obama, and Stanback had envisioned. But Gene Sawyer had no public stature as mayor. “With a very strong mayor” like Washington, a successful outcome was highly plausible, but “now we have a very weak mayor.”

During April’s landfill warfare, Gamaliel held its fourth weeklong training at Techny Towers, and Barack drove out there for several days’ sessions. By then, everyone knew he was leaving. Mary Gonzales was “pretty upset” when she heard, and David Kindler recalled thinking: “there goes one of our best and brightest.” Kindler’s friend Kevin Jokisch remembered telling Greg Galluzzo that Gamaliel would certainly miss Barack, with Greg responding, “We held on to him about as long as we were going to. Barack will probably end up being a United States senator.”

One evening that week, Barack drank beer with Mike Kruglik and talked about what he wanted to do after law school. “Obama is talking about his vision for a very powerful, sweeping organization across black Chicago, of fifty to 150 congregations, that would be highly disciplined, highly focused, professionally organized,” Mike remembered. “This vision … had such a claim on his mind” and Barack was explicit about “coming back to Chicago after Harvard and reengaging in community organizing in a more powerful way.”

Barack was thinking ahead in part because Ken Rolling and Jean Rudd at Woods had decided to fund and commission a series of articles about community organizing in Illinois Issues, the state’s premier public policy journal. Barack accepted an invitation to write one, but a quick deadline loomed. He had decided that he would travel to Nairobi to see Auma and meet the other members of his Kenyan family, but before that he wanted to spend at least three weeks on his own touring the big cities of Europe. Thus he needed to write his article before he left Chicago in late May. His essay would document how his thinking had evolved. Recent African American activism, Barack wrote, had featured “three major strands”: political empowerment, as personified by Harold Washington; economic development, of which black Chicago had seen very little; and community organizing. Barack argued that neither of the first two “offers lasting hope of real change for the inner city unless undergirded by a systematic approach to community organization.” Electing a black mayor like Washington was “not enough to bring jobs to inner-city neighborhoods or cut a 50 percent drop-out rate in the schools,” though such a victory did have “an important symbolic effect.”

At the community level, “a viable organization can only be achieved if a broadly based indigenous leadership—and not one or two charismatic leaders—can knit together the diverse interests of their local institutions.” Barack claimed that DCP and similar groups had attained “impressive results,” ranging from school accountability and job training programs to renovated housing and refurbished parks. Those assertions echoed what Marlene Dillard had heard Barack boast about during their visits to DCP’s funders, yet when he wrote that “crime and drug problems have been curtailed,” he was making his wishfulness give way to fantasy. It was true that “a sophisticated pool of local civic leadership has been developed” thanks to DCP’s recruitment and training efforts, but he admitted that organizing in African American neighborhoods “faces enormous problems.” One was “the not entirely undeserved skepticism organizers face in many communities,” as he had experienced; a second was the “exodus from the inner city of financial resources, institutions, role models and jobs,” as he had seen all too well in Roseland and especially in Altgeld. Third, far too many groups emphasized what John McKnight called “consumer advocacy,” and demanded increased services rather than “harnessing the internal productive capacities … that already exist in communities.” Lastly, Barack declared that “low salaries, the lack of quality training and ill-defined possibilities for advancement discourage the most talented young blacks from viewing organizing as a legitimate career option.”

Barack also argued that “the leadership vacuum and disillusionment following the death of Harold Washington” highlighted the need for a new political strategy. “Nowhere is the promise of organizing more apparent than in the traditional black churches,” if those institutions would “educate and empower entire congregations and not just serve as a platform for a few prophetic leaders. Should a mere 50 prominent black churches, out of the thousands that exist in cities like Chicago, decide to collaborate with a trained organizing staff, enormous positive changes could be wrought in the education, housing, employment and spirit of inner-city black communities, changes that would send powerful ripples throughout the city.”

Barack ended his essay on a revealingly poetic note, writing that “organizing teaches as nothing else does the beauty and strength of everyday people.” When the entire series of Illinois Issues articles was subsequently republished in book form, one reviewer quoted that sentence as the single most powerful statement in the entire volume. But another of Barack’s sentences about organizing was the most revealing of all, for when he wrote that through their work “organizers can shape a sense of community not only for others, but for themselves,” he was publicly acknowledging the self-transformation he had experienced in the homes and churches of Greater Roseland.

As early as his second year at Oxy, Barack had felt “a longing for a place,” for “a community … where I could put down stakes.” The idea of home, of finding a real home, “was something so powerful and compelling for me” because growing up he had been a youngster who “never entirely felt like he was rooted. That was part of my upbringing, to be traveling and always … wanting a place,” “a community that was mine.” His “history of being uprooted” allowed Barack to develop in less than two years what Sheila knew was “his deep emotional attachment to” Chicago, one that was almost entirely a product of Greater Roseland, not Hyde Park.

“When he worked with these folks, he saw what he never saw in his life,” Fred Simari explained. “He grew tremendously through this,” through what he acknowledged was “the transformative experience” of his life, through what Fred saw was “him getting molded.” Greg Galluzzo saw it too and said that Barack “really doesn’t understand what it means to be African American until he arrives in Chicago.” But, working with the people of the Far South Side, Barack “recognizes in them their greatness and then affirms something inside of himself.” Through “the richest experience” of his life, through discovering and experiencing black Americans for the first time, Barack “fell in love with the people, and then he fell in love with himself.”

Years later, Barack admitted that “the victories that we achieved were extraordinarily modest: getting a job-training site set up or getting an after-school program for young people put in place.” And he also knew that “the work that I did in those communities changed me much more than I changed the communities.” Ted Aranda, who had worked for Greg and in Roseland before Barack and whose Central American heritage made it possible for him to be accepted as black or Latino, came to the same conclusion as Barack. “I’m not sure that community organizing really did that much for Chicago,” he reflected. “I don’t know that we had any really tremendous long-term effect.” But Greg, looking back on a lifetime of organizing, understood the great fundamental truth of Barack’s realization: “it’s the people you encounter who are the victories.” For Ted, the disappointments and frustration of organizing radicalized him. A quarter century later, deeply devoted to Occupy, Ted was driving a cab. Greg understood as deeply as anyone that “the great victory of the whole thing is Barack himself.”

In mid-April, the Spertus museum, part of a historic Jewish cultural center on South Michigan Avenue in downtown Chicago, opened a seven-week exhibit depicting the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi henchman who had played such a central role in the anti-Semitic effort to exterminate European Jews. The centerpiece of the exhibition was a continuous film of the trial, supplemented by large photographs and illustrations of newspaper stories plus Jewish artifacts documenting the culture that the Nazi Holocaust had sought to destroy.

The Tribune publicized the opening, and then, less than three weeks later, a front-page Tribune story revealed that anti-Semitism was alive and well even in Chicago’s City Hall: “Sawyer Aide’s Ethnic Slurs Stir Uproar,” read the headline of a story about mayoral assistant Steve Cokely, who had recently delivered four “long and frequently disjointed” lectures under the auspices of Louis Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam (NOI). Tapes of them were on sale at an NOI bookstore, and while anti-Semitism lay at the center of Cokely’s often incoherent ramblings about a “secret society,” he also called both Jesse Jackson and the late Harold Washington “nigger.” Even worse, it was revealed that Mayor Sawyer’s office had known about the recordings for more than four months, and three weeks earlier representatives of the Anti-Defamation League had met with Sawyer about the lectures. But Cokely was still on the mayoral payroll.

Well-known Catholic monsignor Jack Egan labeled Cokely’s retention a “travesty,” but a number of prominent black aldermen defended Cokely. Danny Davis, a supposed reformer from the 29th Ward, called Cokely “a very bright, talented researcher with an excellent command of the English language.” The 9th Ward’s Robert Shaw, citing voters he knew, said, “I don’t think it would be politically wise for the mayor to get rid of Mr. Cokely.” But the Tribune published a blistering editorial, denouncing Cokely as “a hate-spewing demagogue” and “a fanatic anti-Semite” and also lambasting Davis. After five days of feckless indecision, Gene Sawyer finally fired Cokely, but the damage to Chicago, never mind to Sawyer’s indelibly stained reputation, was already done. That evening, at a large West Side rally, Roseland’s Rev. Al Sampson introduced Cokely to a cheering crowd as “our warrior” and declared that “this is a case of Jewish organizations trying to stop one black man from having the right to speak.”

In the middle of this, Barack took Sheila to see the Eichmann exhibit. Both of them would long remember what ensued. In Obama’s later account, in the one single public reference he would ever make to his 1980s girlfriends, he created a character who was a conflation of Alex, Genevieve, and mostly Sheila who goes with him to “a new play by a black playwright.” Several weeks earlier Barack had taken Sheila to see a Chicago amateur production of August Wilson’s powerful 1985 play “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” but Sheila would remember the aftermath of the Eichmann exhibit more vividly than Wilson’s play. As they left, she asked Barack not about Eichmann, but about Steve Cokely and why so many prominent black Chicagoans were defending him rather than denouncing his moronic anti-Semitism. In Obama’s version, his white girlfriend asked about black anger, and he replies: “I said it was a matter of remembering—nobody asks why Jews remember the Holocaust, I think I said—and she said that’s different, and I said it wasn’t, and she said that anger was just a dead end. We had a big fight, right in front of the theater,” and “When we got back to the car, she started crying. She couldn’t be black, she said. She would if she could, but she couldn’t. She could only be herself, and wasn’t that enough.”

Obama would admit that “whenever I think back” to that argument, “it somehow makes me ashamed.” Sheila and Barack did argue angrily that early May night on South Michigan Avenue, but it was because “I challenged him on … the question of black racism,” and his response was so disappointing that their argument became “pretty heated.” As Sheila recalled it, “I blamed him for not having the courage to confront the racial divide between us,” but in retrospect, she concluded that the chasm between them was not racial at all. Instead it lay in the profound tension between Barack’s insistence on “realism,” on pragmatism, and what she believed was simply a lack of courage on his part. “Courage was a big issue between us,” and their arguments over her belief that he lacked it were “very, very painful.”

In early May, Sheila and Barack’s mutual friend Asif Agha returned to Hyde Park after six months in Nepal. He remembers thinking at the time that “they had a good relationship. They were really tight, really solid,” but he also noted that the tensions between them were even greater than they had been during that tumultuous weekend in Madison nine months earlier. Asif thought Sheila had a deeper commitment to their lives together than did Barack, and now, listening to Barack talk about his goals, Asif understood that his friend “wanted to have a less complex public footprint” as a future candidate for public office, particularly in the black community. Asif recalls Barack saying, “The lines are very clearly drawn…. If I am going out with a white woman, I have no standing here.”

Asif realized just how profound the tension had become for Barack between the personal and the political. “If he was going to enter public life, either he was going to do it as an African American, or he wasn’t going to do it.” When asked if Barack had said he could not marry someone white, Asif assented. “He said that, exactly. That’s what he told me.”