По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

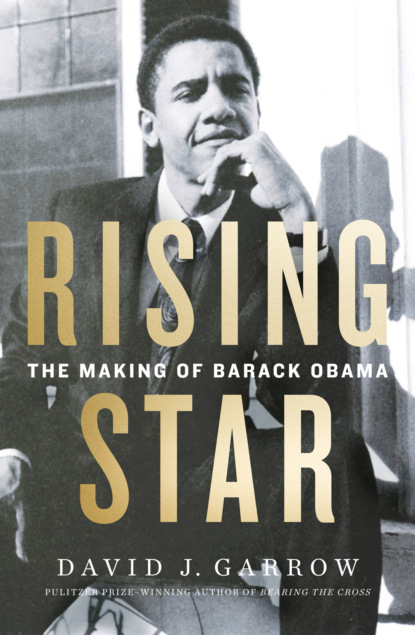

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Even as his time in Roseland was ending, Obama still had to keep up with DCP’s school reform alliance with UNO. Johnnie, Aletha Strong Gibson, and Ann West were more involved than he was, but DCP continued to follow UNO’s Danny Solis and Lourdes Monteagudo. By late April, what was left of Harold Washington’s official Education Summit had failed to endorse reform legislation that was muscular enough to satisfy top reformers like Don Moore, Fred Hess, and Pat Keleher of Chicago United. So UNO and DCP were now formally backing Chicago United’s proposal, which was introduced in the state legislature by Senate Education Committee chairman Arthur L. Berman as S.B. 1837.

When Berman’s committee held a daylong hearing on four competing bills on Tuesday, April 26, Barack and a small group of DCP members including Loretta Augustine, Rosa Thomas, Aletha Strong Gibson, and Ann West traveled to Springfield to lobby legislators and to hear Lourdes Monteagudo testify on behalf of UNO and DCP in support of S.B. 1837. Writing in the Tribune, CPS superintendent Manford Byrd once again energized reform advocates by decrying their attacks on “some monolithic, intractable bureaucracy which in fact does not exist” and claiming that “the school system is broadly understaffed.” First the Sun-Times and then the Tribune began publishing multipart exposés on CPS’s failings. The Trib series debuted with a long feature on one elementary school, “a hollow educational warehouse” that is “rich in remedial programs that draw attention to a child’s failures.” An accompanying editorial warned that “Chicago’s public school system is failing its children and jeopardizing the city’s future.” The next day, in a culmination of negotiations that Don Moore’s Designs for Change colleague Renee Montoya had been conducting with UNO’s Danny Solis, DFC’s reform bill, H.B. 3707, sponsored by African American Chicago representative Carol Moseley Braun, was strengthened with the addition of provisions from Chicago United’s S.B. 1837. UNO and DCP joined in publicly shifting their support to the Braun bill, whose cosponsor was progressive Chicago Puerto Rican state senator Miguel del Valle, and reform energies increasingly coalesced behind the Braun–del Valle measure. In one Trib story, powerful 14th Ward alderman Edward Burke declared that “nobody in his right mind would send kids to public school.” In another, Manford Byrd called himself “probably the most gifted urban administrator in this country” while once again dismissing CPS’s obligations to its students: “When you’re all done, the learner must learn for himself.”

In the final ten days before Barack’s departure from Chicago for his two-month trip to Europe and then Kenya, things came completely apart at 5429 South Harper Avenue. Ever since Barack had transferred to Columbia almost seven years earlier, he had kept a journal, using it to record vignettes that might find their way into a future book and also sometimes for creating drafts of short stories and even letters to friends. Sheila knew of Barack’s practice, and sometime after their heated argument outside the Spertus museum, she decided to take a look at it. Lena Montes heard from Barack what ensued. “She reacted to this journal that he kept under his bed or mattress,” Lena recalled. “I remember when he says that she found some journal, and he talks about somebody in this journal and that she’s upset” after she read it. Barack did not tell Lena whether she was that someone. “Was it a straw that broke the camel’s back? I’m not sure. I just remember him saying that she … was leaving because of this journal.”

Just as Barack was about to leave Chicago, Sheila moved out of their apartment and moved in with her younger friend Simrit “Sima” Dhesi, who had just completed her undergraduate degree at the University of Chicago, and her sister in an apartment four blocks away at 5324 South Kimbark Avenue. Sheila later said that May 1988 “was kind of a blur for me.” Barack mentioned what was happening not only to Lena, but also to Loretta Augustine and even to his archdiocesan friend and Hyde Park neighbor Cynthia Norris. Cynthia understood that Sheila “was upset,” and that the tensions between her and Barack were “because of her race…. Yes, I do remember that.” Norris knew that Barack “had a lot of respect for” Sheila, and from what she knew, “I thought he handled things very, very well.” Loretta remembered it similarly. “He talked to me about her,” she recalled. “We had some really open and candid conversations” about the turmoil. “He obviously cared for her,” and was disturbed by what was happening. “I remember telling him, ‘If it’s really real, what you all have, you’ll come back’ ” after his trip and revive the relationship, “ ‘and if it’s not, you’ll go forward.’ ”

A number of small going-away parties occurred during Barack’s last week before he departed. Reformation Lutheran caretaker John Webster remembered one there, which was also where the small CEN program was now centered; Margaret Bagby recalled another one at St. Catherine’s with catered food. One evening everyone from DCP was invited to a quiet party at a small restaurant in suburban Blue Island. Greg Galluzzo, who had spent so many hours with Barack over the previous eighteen months, “bought him a briefcase and had it engraved” with just “Barack” as a useful going-away present for a law student.

On another night, Barack and Bruce Orenstein went out to drink beer, and Barack asked Bruce what he would be doing ten years from now. “I’m going to be making social change videos,” Bruce answered. Bruce in turn asked Barack the same question. He said he intended to write a book about his upcoming trip to Kenya, and then “I’m going to be mayor of Chicago.” Bruce was taken aback. “That was the first I heard of it,” and “I thought it was a lot of moxie to say that he was going to be mayor.”

A few days later, with Sheila having moved from their apartment, Barack flew east. Almost that same day, a dinner announced several weeks earlier was taking place to honor Frank Lumpkin for the eight years he had devoted to winning recompense for the Wisconsin steelworkers who had been thrown out onto the streets of South Deering back in March 1980.

Frank’s loyalties had not changed. The banquet’s proceeds would “benefit the People’s Daily World,” the newspaper of the Communist Party USA, but that did not deter a trio of notable figures from signing on as public patrons. State Senator Miguel del Valle, sponsor of the pending school reform bill, was one, 22nd Ward reform alderman Jesus “Chuy” Garcia was a second, and Monsignor Leo T. Mahon was a third. “Best wishes to a man who fights for justice,” read Leo’s greeting in the banquet program. Maybe Foster Milhouse and the other right-wing zealots had been right all along, that social justice Catholicism and grassroots communism were indeed one and the same.

Roberta Lynch, CCRC’s first staff organizer, and Tribune business editor Dick Longworth both sent their apologies for being out of town, but a crowd of more than four hundred attended, including U.S. congressman Charles Hayes, a veteran of both labor struggles and the 1966 Chicago Freedom Movement. The Daily Calumet gave the event glowing coverage—“Lumpkin Honored at Dinner”—and three days later editorialized in his honor, simply and accurately calling him “a hero.” After eight years of organizing, Frank Lumpkin had prevailed, and even triumphed.

Just short of three, Barack Obama was headed toward Harvard Law School with the intent of becoming not just mayor of Chicago but eventually president of the United States.

Barack had scheduled a full month to see the great cities of Europe all by himself: Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, and Rome, then to London and from there to Nairobi. He later wrote that he anticipated “a whimsical detour, an opportunity to visit places I had never seen before,” but his memory would be that “I’d made a mistake” in allocating so many days for his European grand tour, because “it just wasn’t mine.” After almost three years of interacting with a dozen or more people almost every single day, now he was entirely alone in countries where he knew virtually nothing of either the language or the culture.

Before the end of May he was busily dispatching postcards to Sheila, Lena, Cathy Askew, and Cynthia Norris from Paris, “some quite humorous,” Sheila remembered. To Cathy, he wrote about how beautiful the buildings were, to Cynthia he described the city’s astonishing appeal: “I wander around Paris, the most beautiful, alluring, maddening city I’ve ever seen; one is tempted to chuck the whole organizing/political business and be a painter on the banks of the Seine. You’ll be amused to know that since I don’t know a word of French, I’m left speechless most of the time. Wish you a fruitful summer. Love, Barack.”

Traveling largely by bus and train, Barack was also reading a journalistic account of modern Africa in preparation for his visit to Kenya. He later told about meeting and trying to converse with a Senegalese traveler on the way from Madrid to Barcelona, but in subsequent years, Barack never referred to any experiences or memories from his four weeks on the continent. By the last weekend in June, he was in London, where Hasan and Raazia Chandoo had moved six months earlier from Brooklyn. The three of them had lunch in a brasserie before seeing Wim Wenders’s new film, Wings of Desire, at a cinema in Notting Hill.

From London Heathrow, Barack flew to Nairobi. His sister Auma and his Aunt Zeituni, the family member who had been the closest to his late father, met him at the airport, but Barack’s suitcase did not arrive until several days later. In preparation for his visit, Barack also had read a brand-new book on Dedan Kimathi, a Kenyan anticolonial warrior of the 1950s whom the British had executed in 1957, but instead of discussing Kenyan history while he stayed at Auma’s apartment, sleeping on her couch, they talked mostly about their extended clan of relatives. “There was never a moment of silence or embarrassed awkwardness” between them, Auma recalled. But with Barack wanting to meet as many family members as possible, “It wasn’t all nice. Sometimes he wanted to see a relative I didn’t really get along with, and he’d be like ‘It’s my right, and I need to see them, and I’m not going alone, and you’re coming with me,’ ” she explained.

Auma always assented, although her thoroughly unreliable Volkswagen Beetle was their primary mode of transport around sprawling Nairobi. One drive took them to see Auma’s mother Kezia and her sister Silpa Jane, who six years earlier had been the telephone caller who told Barack of his father’s death. On another, Zeituni took Barack to meet her older sister Sarah, who was living in a scruffy slum. But the most difficult visit was to Ruth Baker Ndesandjo, whose son Mark—Barack’s younger brother—was home for the summer and about to begin graduate school at Stanford after having just graduated from Brown. Barack later imagined that Ruth had invited him and Auma to come for lunch, but both Ruth and Mark convincingly remember Barack and Auma turning up with no forewarning. As Mark recounts, a “very awkward, cold” encounter ensued, as Ruth found the unexpected arrival of her ex-husband’s namesake “pretty traumatic.” Years later she recalled, “I closed up. I had nothing to say,” for “I didn’t have the capacity to talk with him or exchange with him because he was a reflection of a man I hated. So I didn’t want anything to do with him.”

Barack wanted to see more of Mark, and they arranged to have lunch a few days later. Mark remembered thinking that Barack had a “cold” demeanor, “absolutely no sense of humor,” and “wanted to shut out any emotional involvement” with his likewise half-Luo, half-white American brother, especially when Mark bluntly stated that “our father was a drunk and he beat women.” Barack later admitted that meeting Ruth and Mark, and grasping at least in part how abusively his father had treated them, affected him deeply. “The recognition of how wrong it had all turned out, the harsh evidence of life as it had really been lived, made me so sad,” far more so than he had been three years earlier when he had learned during Auma’s visit to Chicago just how deeply tragic a life Barack Obama Sr. had led.

During Barack’s second week in Kenya, Auma took him on a wild-game safari, and then the two of them plus Zeituni and Kezia took a train northwest to Kisumu and then a jitney bus to the family homestead at Nyang’oma Kogelo. There Barack met Sarah, the stepmother who had raised his father. Barack asked her if anything of his father’s still survived. “She opened a trunk and took out a stack of letters, which she handed to me. There were more than thirty of them, all of them written by my father,” carbon copies “all addressed to colleges and universities all across America” from when Obama Sr. was seeking admission to the University of Hawaii and other colleges. Holding them reminded Barack of the letters he had written a few years earlier, “trying to find a job that would give purpose to my life.”

That moment, even more than standing at his father’s unmarked grave in the side yard of Sarah’s small, tin-roofed brick home, marked the most powerful and direct paternal link Barack had ever experienced. The connection was underscored when relatives remarked that Barack’s voice sounded “exactly how his father spoke.” Barack’s visit to Nyang’oma Kogelo, like his earlier one to Aunt Sarah in that Nairobi slum, made Barack realize that his Kenyan relatives’ lives sometimes paralleled those of people whom he knew in Altgeld Gardens. Pondering John McKnight’s analysis, in Kogelo Barack wondered whether “the idea of poverty had been imported to this place, a new standard of need and want.”

Barack later wrote that while in Kenya, “for the first time in my life, I found myself thinking deeply about money,” perhaps foreshadowing the debt load he was about to take on to follow his father’s footsteps to Harvard rather than attend Northwestern cost free. He told Auma that his decision to attend law school was a response to his experiences in Chicago, because as a community organizer he could not “ultimately bring about significant change.” Back in Nairobi, everyone went to a photography studio so that a family portrait could be taken, and Barack and Auma made a brief visit to an elementary school so that he could meet his youngest sibling, George, the son of Jael Atieno.

One night Auma took Barack to meet one of her former teachers, a woman who had also known their father. Barack recounted her presciently telling him that being a historian “requires a temperament for mischief” and instructing him that when confronted with roseate fictions, “truth is usually the best corrective.” For his final weekend in Kenya, Auma and Barack took a train eastward to the country’s second largest city, coastal Mombasa. Overall, “it was a magical trip,” Barack remembered, an immersion into the life of the father who had abandoned him, an immersion that “made me I think much more forgiving of him” than he had been before experiencing Luo life and culture for the very first time.

Before the end of July, Barack returned to Chicago, where he was all alone in the 5429 South Harper apartment until the lease expired in early August. When Asif’s friend Doug Glick stopped by, he was struck by how different the place looked without Sheila. But Barack and Sheila’s two months apart had not ended the relationship between them. Johnnie Owens had run into Sheila in Hyde Park during the summer and remembers how “upset,” even “brokenhearted” she seemed about what had happened just before Barack’s trip. But Barack’s more-than-weekly letters from Europe and Kenya had rebuilt much of their bond. Even so, in little more than two weeks he had to head to Massachusetts before the start of Harvard’s fall semester. He needed to purchase a better car than the blue Honda Civic that he had driven from Manhattan just over three years earlier, and he replaced it with an off-yellow 1984 Toyota Tercel hatchback he bought for $500 from a suburban police officer.

Barack also wanted to be sure that Johnnie’s transition was going as smoothly as possible, not just at DCP, where everyone already knew Johnnie, but also with DCP’s downtown supporters. “He made sure that the leaders were comfortable,” Johnnie remembered, but “the main thing he did was transfer those financial funder relations” with Jean Rudd at Woods, Anne Hallett at Wieboldt, and Aurie Pennick at MacArthur. Just a few weeks later, MacArthur would award DCP its second annual $20,000 grant. Barack “left the organization in a very good position,” Johnnie explained, and the effort Barack put into the transition further showed that he intended to return to Chicago after law school.

Barack’s greatest disappointment was the lack of state funds to expand DCP’s after-school tutoring program, but with state government consumed by the struggle over Chicago school reform, the legislature had remained in session beyond its normal end-of-June adjournment to pass a compromise bill. At the end of May, reform forces had reunified themselves into a new coalition called the Alliance for Better Chicago Schools, or ABCs, with UNO playing a lead role and DCP a minor one. A massive June 6 rally had called upon reform supporters to make their case in person to state legislators in Springfield, and the slogan “Don’t come home without it!” became reformers’ new rallying cry.

The Chicago City Council approved a vote of no confidence in Manford Byrd by 39 to 4, soon followed by the resignation of a board of education member who now felt similarly. “I assumed education was the first priority of the whole system, and it is not,” retired business executive William Farrow announced. Down in Springfield, House speaker Michael J. Madigan brought the interested parties together for marathon negotiation and drafting sessions in his office. Danny Solis and Al Raby both took part, but the most influential participant was one of Madigan’s deputies, Chicago state representative John Cullerton. By the end of June Al Raby was proclaiming that “real reform of Chicago schools is within our grasp,” and on Saturday, July 2, both houses of the state legislature passed a compromise bill. Failure to adopt the measure by the end of June would delay its effective date for a year, but Chicago United’s Patrick Keleher said the bill represented “as much if not more than any of us had hoped for.”

Barack heard far less encouraging news about his other top concern, the Southeast Side landfill tussle. Mayor Sawyer’s new UNO-and-DCP-dominated task force had held additional public hearings during June, and in late July met privately with both city and Waste Management representatives. By the end of the summer, its report to Sawyer was complete, though several weeks would pass before cochairs Loretta Augustine and Mary Ellen Montes joined the mayor at a City Hall press conference. “The city of Chicago is facing a crisis,” Sawyer announced. “We’re going to have to bite the bullet and do some things that we would prefer not to do,” namely allow the O’Brien Locks site to become a landfill. That outcome had always looked inevitable, but Bruce, Barack, and Mary Ellen’s strategic success in blowing up the Fitch negotiations meant that any landfill now would be controlled not by Waste Management but by the Metropolitan Sanitary District.

Alinsky-style warfare had not only destroyed a likely Southeast Side consensus to accept a quid-pro-quo deal with Waste Management, it had deprived those neighborhoods of the multimillion-dollar bounty WMI had been willing to pay. It was a debacle all around. A decade later, Jim Fitch would be sent to federal prison for eighteen months and fined $1 million for looting bank funds throughout the 1980s in order to contribute to Southeast Side politicians. Another decade further on, with UNO having abandoned South Chicago and transformed itself into something that bore no resemblance to the organization that Mary Gonzales, Greg Galluzzo, and Mary Ellen Montes had originally built, UNO would endorse a Waste Management effort to expand Southeast Side landfills.

In Barack’s final days before he left for Harvard, the DCP members to whom he had become closest held a small barbecue for him at Loretta Augustine’s home. He assured them, “If you have problems, you can contact me and I’ll do what I can.” He also had a trio or more of presents for them, wooden figurines he said he had brought back from Kenya. Dan Lee remembered that Barack gave him “a statue of a warrior with a chipped beard.” Cathy Askew recalled admiring a giraffe, but “I think he gave me the zebra because of the mixed black and white stripes,” an acknowledgment of their disagreement about biracial identity.

Mary Ellen Montes did not attend that party, but one evening Barack took her out to dinner at a downtown restaurant. “We had our own kind of little going-away party, Barack and I, and it was just Barack and I,” she remembered. Barack promised to write to her, and he would, but that night, or the next morning, was the last time Lena and Barack would see each other in person.

With the lease on the South Harper apartment expiring several days before Barack planned to leave, he joined Sheila in her apartment on South Kimbark. She was preparing to leave Chicago soon too to begin her dissertation fieldwork in South Korea thanks to a Fulbright fellowship, and when she joined Barack for a farewell visit to Jerry Kellman’s home, they had a question for Jerry and his wife. “They come to dinner at our house,” Jerry remembered, “and they say ‘Could you please keep this cat?’ ” The Kellmans willingly agreed to give Max a new home. “Barack was not sad to give Max away,” Sheila explained, but for Max the transition was all to the good, and he would enjoy eight years of love with the Kellmans.

Jerry knew that Barack and Sheila were not breaking up, just headed in different geographical directions. He thought “they had a great, healthy relationship,” although one that was now constrained by Barack’s career plans. “By the time Barack left to go to law school, he had made the decision that he would go into public life,” Jerry realized. Indeed, “my sense is that Barack’s dream was to come back and possibly become mayor of Chicago.”

But Barack was still trapped between his belief in his own destiny and his deep emotional tie to Sheila. One day that final week “he said that he’d come to a decision and asked me to go to Harvard with him and get married, mostly, I think, out of a sense of desperation over our eventual parting and not in any real faith in our future,” Sheila recalled. Her memory was reminiscent of Genevieve’s from three summers earlier, when Barack had asked her to come to Chicago with him, and Genevieve had thought Barack was asking her only because he was certain her answer would be no.

Now, once again, the answer was no, and Sheila was upset by Barack’s presumption that she should postpone, if not abandon, her dissertation research in order to accompany him to Harvard. A “very angry exchange” followed, with Sheila feeling that Barack believed that his career interests should trump hers.

Barack started eastward within a day or two, knowing he could stay temporarily with his uncle Omar, who had remained in greater Boston ever since first arriving there thanks to his older brother a quarter century earlier and whose phone number and address Aunt Zeituni had given Barack while he was in Nairobi. But before heading back down Stony Island Avenue to the Skyway and then the Indiana Toll Road, Barack needed to have one other conversation.

“I was a little troubled about the notion of going off to Harvard. I thought that maybe I was betraying my ideals and not living up to my values. I was feeling guilty,” he told a college audience just six years later. Barack called Donita at Trinity and made an appointment to see Jeremiah Wright to seek his counsel about those doubts. In a way, it was just like the conversation he had had nine Augusts earlier, in Honolulu, when eighteen-year-old Barry had gone to visit Frank Marshall Davis before leaving for Occidental and life on the mainland.

Years later, before their relationship was torn apart, Wright would say that Barack was “like a son to me.” One of the most knowledgeable and savvy women in black Chicago would make the same point: “Jeremiah Wright was the black male father figure for Barack,” she emphasized. “Don’t underestimate the influence that Jeremiah had on Barack.” Wright would not specifically remember their conversation that August day, but Barack always would. In a way, it was a three years’ bookend to the admonishing monologue about being a do-gooder that Bob Elia have given him that night in the motel lobby on South Hermitage Road.

That exchange would stay with Barack always, as would this one, but the substance of Wright’s message was identical to the warning that old Frank had voiced: “You’re not going to college to get educated. You’re going there to get trained,” trained “to manipulate words so they don’t mean anything anymore,” trained “to forget what you already know.” Wright’s message was just five words, ones that would ring in Barack’s ears for the entire two-day drive eastward: “Don’t let Harvard change you!”

Chapter Five (#ulink_c7d7289a-c9eb-5c50-89ea-50e49b260a4c)

EMERGENCE AND ACHIEVEMENT (#ulink_c7d7289a-c9eb-5c50-89ea-50e49b260a4c)

HARVARD LAW SCHOOL

SEPTEMBER 1988–MAY 1991

Omar Onyango Obama, the younger brother whom Barack Obama Sr. had helped come to the United States in 1963 to attend high school, was by August 1988 an unmarried forty-four-year-old store clerk living in central Cambridge. Omar’s apartment at 48 Bishop Allen Drive was his twenty-seven-year-old nephew’s first destination when Barack exited the Massachusetts Turnpike upon arriving from Chicago. Omar had never completed high school, but his mundane work life had not kept him from developing keen political interests. “I am a Pan-Africanist,” he wrote in a letter to Ebony magazine, one who shared “the dreams of brothers Marcus Garvey, W. E. B. Du Bois and Malcolm X.” Barack had never met his uncle Omar, but Omar happily hosted him while Barack scoured the Boston Globe’s classified ads looking for a place of his own.

John “Jay” Holmes owned the handsome, almost century-old Queen Anne–style Langmaid Terrace apartment building at 359–365 Broadway in Somerville’s Winter Hill neighborhood. Harvard Law School was a twelve-minute, two-and-half-mile drive away, but for $700 a month a one-bedroom basement-level “garden” apartment there offered more private and spacious quarters, including a nice exposed-brick living room, than other rentals closer in. By the end of August, Barack was happily settled at 365 Broadway #B1, and on September 1, Harvard Law School (HLS)’s two-day registration and orientation for first-year students—“1Ls”—got under way on its multibuilding campus on the east side of Massachusetts Avenue, a short distance north of Harvard Square.

The entering class of 1991 numbered 548 students, selected from among seventy-one hundred applicants. Forty percent of the new class were women, and 22 percent were nonwhite, including fifty-seven African American students, of whom almost two-thirds were women. That was impressive diversity: the 2L and 3L classes had started with sixty and seventy-three African Americans, respectively. While the average age of the new 1Ls was twenty-three, with an overwhelming majority coming directly from their undergraduate studies, 5 percent of the class was over the age of thirty, including “many students who experienced the ‘real world’ before coming to law school,” according to the weekly Harvard Law Record. Word among the faculty was that “preferences for applicants who had taken time off, engaged in public works, or participated in other significant outside activities or experiences” had played a significant role in admissions decisions.

The school had an illustrious reputation but a deeply troubled internal culture. For three years, the faculty had been embroiled in toxic ideological warfare that had seen four junior faculty members denied permanent appointments, the first such tenure denials in seventeen years. That quartet was seen as “crits,” or proponents of “critical legal studies” (CLS), a left-wing school of thought that viewed legal rules and doctrines as inherently conservative rather than politically neutral. While several prominent crits, including CLS’s most erudite proponent, Roberto Mangabeira Unger, a Brazilian legal philosopher, were senior members of the Harvard law faculty, other full professors, including Robert C. Clark and David Rosenberg, were perceived as conservative “law and economics” devotees who were generally hostile to the work of crits.

James Vorenberg, dean of the law school since 1981, had announced his upcoming departure from that post in April 1988, just as tensions over a second issue of faculty composition—racial and gender diversity—were reaching a new peak as well. Seven years earlier, the roughly sixty-member Harvard law faculty had included just one tenured woman and a single tenured black male, who passed away in 1983. By 1988 there were five senior women, all white, and two tenured black men—Derrick Bell and Christopher Edley—with one more woman and three additional black men—Charles Ogletree, Randall Kennedy, and David Wilkins—all on the cusp of consideration for permanent appointments. In May 1988, the Black Law Students Association (BLSA) occupied Vorenberg’s office in a “study vigil” to protest the school’s failure to appoint additional minority faculty, with Professor Bell and legendary civil rights organizer Robert Moses addressing a student rally the next day.

Even with their healthy representation in each entering class, Harvard’s black law students felt a constant need to prove they were just as qualified as their white classmates to succeed at HLS. “Everything here says you can’t do it,” graduating BLSA president Verna Williams remarked in a fifty-page 1988 BLSA publication. “BLSA fights that negative attitude, and that builds you up.” The 1988 class had found BLSA in “disarray” upon their 1985 arrival and had worked to show that black students could attain leadership positions in multiple student organizations. By their 3L year, they had succeeded, with 1987–88 marking “the first time in HLS history that black law students, in significant numbers, had not only gotten involved in campus organizations outside of BLSA, but had done so with such success and capability that their peers … asked them to lead the organizations.”

But law students of all races were deeply unhappy with the institution’s culture. In the late 1980s “attending Harvard Law School was a miserable experience for the majority of its students,” one highly supportive alumnus later acknowledged, and a 1988 forum soliciting student input regarding the selection of Vorenberg’s successor instead focused on “the alienation students have felt from the law faculty,” the Harvard Crimson reported. “I don’t always feel that professors are here who can teach,” one 3L woman told the paper. “Law school seems to exist primarily for the professors.” Another 3L wrote in a subsequent memoir, “I didn’t know any of my law school professors,” and described how “the one thing that actually drew the student body together was a widespread disenchantment with our teachers.” He also recounted that although 70 percent of his classmates had arrived at Harvard expressing an interest in practicing public interest law, only six out of 474 actually accepted legal-services jobs after graduation.

Four years earlier a young sociologist, Robert Granfield, had begun questioning scores of Harvard law students to analyze the “complex ideological process that systematically channels students away from socially oriented work.” He concluded that “students come to believe that effective social progress occurs primarily through the use of elite positions and resources.” Graduates “feel that they have emerged with their altruism intact, while having actually been co-opted” into joining large corporate law firms as a result of their acculturation at what he called “a tremendously powerful co-optive institution.” The bottom line was that “employment in organizations designed principally to serve the corporate rich came to be seen as highly compatible with public service ideals.”

BLSA’s long, mid-1988 report included a four-page essay entitled “Minority and Women Law Professors: A Comparison of Teaching Styles,” written by a graduating 3L who had accepted a job at the Chicago office of Sidley & Austin, one of the country’s most prominent corporate law firms. Michelle Robinson had taken Criminal Law with Charles Ogletree and Family Law with Martha Minow, a young professor who had been awarded tenure in 1986 and whose father was one of Sidley & Austin’s best-known partners. Robinson briefly interviewed both Ogletree and Minow, as well as David Wilkins, because she saw each of them as highly atypical faculty members: “each one of these professors spends an enormous amount of time with students—particularly minority and women students,” she wrote. Robinson clearly admired Minow, writing that “sitting in her Family Law class is like sitting in the studio audience during a taping of the Phil Donahue Show.” Not all compliments are actually flattering, but it was David Wilkins, in just his second year of teaching at Harvard, who supplied the real gist of Robinson’s essay. “The problem here is that only about ten percent of the professors care enough about students to spend time with them,” he bluntly told her. “Consequently, this ten percent gets a disproportionate share of students to counsel.” He pointed out further that they bore that heavy ancillary burden while also striving to write the law review articles necessary for promotion to tenured full professor.

Like many of her fellow students, Robinson lamented the law faculty’s relative lack of “people who possess the enthusiasm, sensitivity and ingenuity necessary to bring excitement back into the classroom.” She also decried the school’s lack of interest in hiring a more diverse faculty and said it “merely reinforces racist and sexist stereotypes,” attitudes that also were manifest in “the rude statements and questions posed by students”—white students—“to Professors Wilkins and Ogletree.” But as Robinson’s acceptance of Sidley & Austin’s highly remunerative job offer underscored, another defining element of the law school’s culture was that the high cost of a Harvard education provided a powerful incentive for graduates to take the best-paying jobs available.