По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

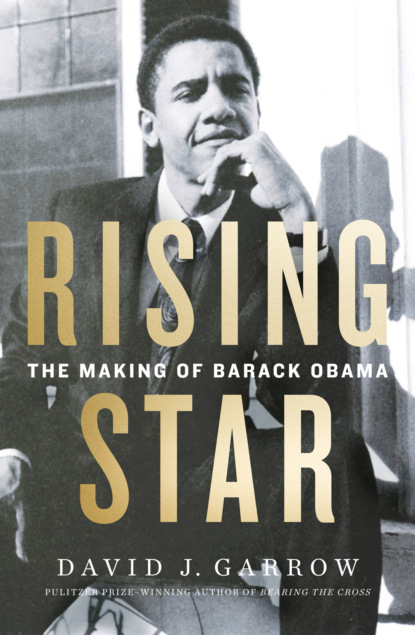

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

During the first week of January 1987, Gamaliel held a three-day retreat for its seventeen organizers, plus Ken Rolling from Woods, at a Holiday Inn in south suburban Matteson. More important, Obama was now meeting for at least an hour a week, one on one, with Greg Galluzzo to talk about his Developing Communities Project work. Greg’s monthly calendar recorded the regularity of their discussions: Thursday morning, January 15; Wednesday lunchtime, the 21st; Friday morning, the 30th. On Wednesday, February 4, they spoke for two and a half hours; on Monday, February 9, for two more. Wednesday, the 11th, Greg came to Barack’s apartment; Tuesday, the 17th, they met for another ninety minutes—ten hours of conversation in just thirty days.

As anyone who knew Galluzzo would testify, he was so intense that no discussion with him ever devolved into idle chitchat. Deeply committed to his belief that “the essence of organizing is the transformation of the person” into someone who was “serious about being a power person in the public arena,” Greg’s self-confidence and challenging interpersonal style was robust indeed. True to the Alinsky tradition, Greg’s insistence that people unapologetically seek power for themselves was completely nonideological and entirely pragmatic: “Find out what people want,” he said, “and then we’ll decide what we’re going to do about it.” He also agreed with the Alinsky tradition of avoiding insoluble “problems” while constantly searching out winnable “issues.” Greg knew it was essential to “learn politics as the art of the possible.” He believed that, properly taught, “community organizers are pragmatists” who firmly appreciate that “in 99 percent of the cases the end does justify the means.” In addition, an Alinsky organizer assumed a dual public and private life. As one veteran put it, “you compartmentalize life and then it allows your consciousness to go to the beach.”

On the Far South Side, parents in Altgeld Gardens, aided by Barack, maintained their boycott of the Wheatley Child-Parent Center until January 20, when the CPS provided documentation that no asbestos had been found in the school. The boycott energized Altgeld residents’ interest in Hazel Johnson’s People for Community Recovery, and Mayor Washington spoke at a PCR meeting that drew several hundred people. The Tribune reported a new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency study that had found that “more than 20,000 tons of 38 toxic chemicals are emitted into the air each year in the Lake Calumet region on the Southeast Side.” The Daily Calumet reported that Waste Management’s 1986 quarterly earnings were up an astonishing 349 percent, and a WMI representative, Mary Ryan, had quietly begun speaking with interested parties about WMI’s desire to add the O’Brien Locks site as an adjoining landfill to its huge CID dump just east of Altgeld. Ryan spoke first with Bruce Orenstein, UNO’s new Southeast Chicago organizer, and Mary Ellen Montes. “Waste Management would be very willing to bring benefits to the community, gifts to the community, for your acquiesence, your agreement to allow us to dump there,” Orenstein remembers Ryan explaining. He and Lena were intrigued by Ryan’s offer but wanted to ponder what dollar amount would be appropriate and how such a sum should be managed and invested. Ryan also called on George Schopp at St. Kevin, Dominic Carmon at Our Lady of the Gardens, Hazel Johnson of PCR, civic activists ranging from Marian Byrnes to Foster Milhouse, and Obama on behalf of DCP. In mid-February Lena, Bruce, Hazel, and Barack met to discuss how to respond to WMI’s bold initiative.

But Obama’s top priority in early 1987 was recruiting supporters for his Career Education Network. In addition to Dan Lee, Aletha Strong Gibson, and Isabella Waller, the three DCP members most interested in the proposal, he also discussed his idea with four people he already knew: Dr. Alma Jones, the indomitable principal of Carver Primary School in Altgeld; John McKnight, whom he was getting to know well through Gamaliel; Anne Hallett of the Wieboldt Foundation, with whom he had spoken in November and who had given DCP a $7,500 grant; and John Ayers, a close friend of Ken Rolling’s who had observed DCP’s “Let Loretta speak!” meeting with Maria Cerda and worked for the prestigious Commercial Club. McKnight and/or Hallett suggested that Barack approach Fred Hess, and Hess recommended that Barack introduce himself to Gwendolyn LaRoche, the education director of the Chicago Urban League. LaRoche scheduled a thirty-minute appointment, but her conversation with the “very polite young man” lasted “about two hours.” LaRoche explained that much of the federal and state funding that was supposed to go to schools with high concentrations of poor students was instead being spent on administrative jobs at CPS headquarters. “Barack was very much interested in” how “our kids were being cheated” by CPS, Gwen LaRoche Rogers recalled years later. The Urban League was already sponsoring after-school tutoring programs in churches, an approach that would fit perfectly with DCP’s congregational base.

Obama reached out as well to Homer D. Franklin at Olive-Harvey, a fifteen-year-old community college just north of 103rd Street that was named for two African American Medal of Honor recipients, and to George Ayers at Chicago State University, on the south side of 95th Street. Olive-Harvey would be crucial to Barack’s hope of establishing a job-training program focused upon public aid recipients and especially Altgeld Gardens residents. DCP also won board of education president George Munoz’s agreement that CPS counseling specialists would cooperate with DCP’s effort.

Obama would later say that his Far South Side work was inspired by what he knew about the history of the black freedom struggle during the 1950s and 1960s, and in late January 1987, Chicago’s public television station, WTTW, joined in the nationwide PBS broadcast of the six-part landmark documentary series Eyes on the Prize on Wednesday evenings at 9:00 P.M. These first six episodes covered only the years from 1954 to 1965—a second set of eight programs three years later would include an episode focusing on Chicago’s own 1965–1967 Freedom Movement—but the Defender and the Tribune publicized and praised the early 1987 Eyes telecasts. The Defender also accorded a full-page headline to a review of a new biography of Martin Luther King Jr., calling the book “a magnificent and unvarnished study” based upon “exhaustive research.” Written by one of Eyes’ three senior advisers, the book devoted the better part of two long chapters to King’s role in the Chicago Freedom Movement. Those chapters highlighted how one particular Chicago civil rights activist, thirty-two-year-old schoolteacher Al Raby, had convinced King to come to Chicago and had been at his side throughout every day of the 1966 campaign.

In subsequent years, Raby played a significant role in the 1970 revision of Illinois’s state constitution before running unsuccessfully for 5th Ward alderman in Hyde Park. Eight years later, Harold Washington’s top political adviser, Jacky Grimshaw, persuaded Washington to name Raby his campaign manager for his successful 1983 primary campaign against incumbent mayor Jane Byrne. But as Raby’s longtime closest friend, Steve Perkins, later explained, “Al and Harold just didn’t have good chemistry” and indeed “rarely communicated.” Once Washington triumphed, Raby was “moved aside” and “totally marginalized.” Raby ran for Washington’s now-vacant congressional seat, but the new mayor backed labor veteran Charles Hayes, and Raby’s loss seemingly left him with “no future in Chicago.” He accepted the number two post at Project VOTE!, a trailblazing voter registration organization, and moved to Washington, D.C.

Eighteen months later, in early 1985, Raby returned to Chicago after Jacky Grimshaw convinced Harold Washington to name him as the new head of the city’s Commission on Human Relations. But Al Raby was no one’s bureaucrat. Instead, as Steve Perkins would emphasize, notwithstanding how Al was “an intensely private person,” he was also “a continual talent scout, always looking for new activists with special gifts.” Judy Stevens, Raby’s deputy at the commission, also watched as “he mentored people.” By early 1987 Al was living in Hyde Park with Patty Novick, who two decades earlier had introduced Al and Steve.

One morning Obama joined Patty and Al for breakfast, and soon after, Al called Steve: “he wanted me to come have breakfast with Barack, and so we had breakfast at Mellow Yellow,” a well-known Hyde Park eatery. “Barack was fabulous. He was smart, he was articulate—it was a joy to meet him,” Steve remembered. Patty recalled how “I want you to talk to” was one of Al’s favorite phrases, and one day in early 1987 Raby took Barack to City Hall and introduced him to Jacky Grimshaw, who was serving as Washington’s director of intergovernmental affairs. According to Jane Ramsey, the mayor’s director of community relations, “Al was all over the place,” and Grimshaw can picture Barack that day: “he was a kid,” although a “very serious” one. But Raby was far more influenced by his experiences with King than by city politics. “Al was determined to create a base for a long-term movement,” Steve Perkins emphasizes.

In early 1987, Harold Washington’s aides were focused on his reelection, and Jane Byrne was mounting a stiff challenge in the upcoming Democratic primary. The mayor’s employment aide Maria Cerda had made a point of renting a portion of Local 1033’s East Side union hall as a new jobs-referral site. Maury Richards said that income “was just totally instrumental in keeping us afloat” and “at a critical time.” Soon Richards was put on the city’s payroll part-time, allowing him to hold the local union together while also staffing the Dislocated Worker Program. Washington needed all the votes he could get in Southeast Side precincts, and Maury was deeply thankful to Washington, whom he described as “a great guy.” Eight days before the election, steel was poured at South Works for the first time in seven months, another small victory for South Side steelworkers.

Just before midnight on February 25, Byrne conceded defeat after mounting a “powerful challenge” to Washington, whose 53.5 to 46.3 percent victory “was much closer than the mayor’s strategists had been counting on,” the Tribune reported the next day. But the headline “Mayor’s Tight Win Just Half the Battle” pointed to the April 7 general election, when Washington would face two white Democrats running as independents: Cook County assessor Tom Hynes, a relative “Mr. Clean” by Chicago standards, and 10th Ward alderman Ed Vrdolyak, the mayor’s worst nemesis. Fewer white voters had turned out to support Byrne than had voted against Washington in 1983, though the mayor’s own white support had barely risen from four years earlier. A larger, more heavily white electorate was possible on April 7, but Washington was “a heavy favorite” as long as both Hynes and Vrdolyak remained in the race.

On the Far South Side, Obama was trying to generate more grassroots support for his Career Education Network idea. Five high schools drew students from major portions of DCP’s neighborhoods: Harlan at 96th Street and South Michigan Avenue, Corliss on East 103rd Street, Julian at 103rd and South Elizabeth in Washington Heights, Fenger on South Wallace Street at 112th Street, and Carver down in Altgeld Gardens. Barack and a number of DCP’s most active members, including Dan Lee and Adrienne Jackson, began staging modest street corner demonstrations near the troubled high schools to draw attention to the schools’ horrible dropout rates, especially among young black men. One morning that spring, they held a rally on busy 111th Street a block north of Fenger, where one year earlier a Defender photo of the school’s top academic achievers had pictured one dozen African American women. Among the passersby was Illinois state senator Emil Jones Jr., whose office was less than two blocks away. “I stopped to see what they were out there for,” Jones later explained. He knew Adrienne Jackson, and she introduced Jones to Obama. “Barack was part of the group,” Jones recalled. “I met him on the corner.” But Jones was not happy to see protesters just down from the 34th Ward headquarters. “You have a lot to learn,” he told Adrienne and Barack. “You’ll get more flies with honey than you will the way you all are doing this.”

Jones viewed them as an “in-your-face type of group,” but invited them to his office, where they laid out their dropout prevention goals, and particularly Obama’s hope of winning state funding for his Career Education Network. Jones thought Obama was “very bright and intelligent and very sincere” but also “very aggressive and somewhat pushy.” More seriously, Jones thought Obama “was naive as related to the political situation.” He did not know that in most any Chicago ward organization, real power was with the ward committeeman, who often doubled as alderman, and not with state legislators, even one with the grand title of senator. In addition, the Illinois legislature was made up of two very separate chambers.

“We can work together,” Jones told Obama, but “you haven’t got a deal on the House side” until a supportive state representative was recruited. But with Jones’s backing, Barack now had a significant state political figure, in addition to Al Raby’s City Hall connections.

But still Obama’s biggest challenge was expanding DCP’s base beyond Roman Catholic parishes like Holy Rosary and St. Catherine and PTA groups from middle-class Washington Heights. His first significant recruit was Rev. Rick Williams, the Panamanian-born pastor of Pullman Christian Reformed Church (PCRC) on East 103rd Street. PCRC had been founded in 1972 as a “mission” church when Roseland’s four long-standing Christian Reformed churches left the neighborhood in the wake of its rapid racial turnover. Williams arrived at PCRC in 1981, and by early 1987 PCRC possessed the most racially integrated congregation on the Far South Side.

One day Obama and Adrienne Jackson called on Williams, who was immediately impressed by Barack’s “humility” and “his ease with people.” Williams also saw that Obama’s focus on growing DCP was rooted in an IAF-style worldview: “they wanted to work with churches because churches have values and churches have people and churches have money.” But Williams also knew that building an ecumenical base for DCP would be difficult because “these churches are of different persuasions, denominations, ways of thinking…. Creating community out of these churches” would be “a very complicated thing,” and even more difficult for some pastors because Barack himself was “not a church-going person.” But because Obama was “a principled person,” Williams readily signed on, telling Barack, “You are wise beyond your years,” when he and Adrienne departed.

Just a block west of Holy Rosary was Reformation Lutheran Church. One young woman from that congregation, Kimetha Webster, had been active in DCP for months, and sometime that spring, she took Barack and Bill Stenzel there and introduced them to the church’s new young pastor, Tyrone Partee, as well as her father, John Webster, a congregation mainstay and the church’s caretaker. If Obama’s Career Education Network became a reality, its after-school counseling and tutoring efforts would require more space than Holy Rosary alone could offer. Obama explained DCP’s aspirations before asking, “Pastor, do you think it’s possible that we could do some things here at the church?”

Partee was, like Barack, just twenty-five years old, and he came from a politically active family. His uncle Cecil Partee, the longtime committeeman of the 20th Ward, had served for two decades in the Illinois state legislature, including one term as president of the state Senate, a landmark achievement for an African American in the thoroughly white Illinois state capitol. Cecil Partee also was a crucial supporter of Harold Washington and now served as city treasurer. Tyrone immediately offered Barack Reformation’s support and space in its Fellowship Hall. “I believed in what he was doing for our community,” Partee said. But getting to know John Webster was even more valuable because he offered to show Barack around Roseland. “Everybody knew Mr. Webster,” Partee recalled. “He knew the good and the bad on everything.”

A third pastor Barack called upon was Alonzo C. Pruitt, a former Chicago Urban League community organizer and now the young vicar of St. George and St. Matthias Episcopal Church on 111th Street. St. George was known for its weekday program that each morning fed about forty hungry people, some of whom lived at the nearby Roseland YMCA and others in the neighborhood’s abandoned buildings. Pruitt was also impressed with Obama and agreed to lend his name to DCP’s efforts.

Among Roseland’s many churches, the faith most widely represented was not Catholic, Lutheran, Christian Reformed, or Episcopal; it was Baptist. Baptist churches were freestanding and independent, not tied to any denominational hierarchy or bishop, and their pastors could be as iconoclastic as they chose to be. By early 1987, central Roseland’s most immediately pressing problem, as Pruitt’s feed-the-hungry program highlighted, was the increase in the number of homeless people. That problem had its roots in the foreclosed loans and boarded-up homes that had increased dramatically in the past seven years due to the loss of tens of thousands of jobs, in the steel mills and also at previously vibrant manufacturing firms, from Dutch Boy and Sherwin-Williams paints to Carl Buddig meats and the Libby, McNeill & Libby food cannery.

Late in 1986 the Daily Calumet’s superb steel reporter, Larry Galica, in an article about the human costs of unemployment, quoted Alonzo Grant, a black Roseland homeowner with a wife and three children who had lost his job at South Works and not found a new one. “I have no income whatsoever. I can’t receive public aid. I’m three months behind in my house mortgage payments, I’m two months behind in my car payments, and I’m behind in my utility bills.”

Starting in late 1985, Neighborhood Housing Services (NHS), a ten-year-old foundation-supported organization whose mission was to help homeowners in declining, heavily minority neighborhoods, began planning a Roseland program at the request of Ellen Benjamin, executive director of the Borg-Warner Foundation. Benjamin had been interested in Roseland for several years, and within six months, the Borg-Warner Foundation committed $450,000 to NHS Roseland. Chicago’s Department of Housing soon matched that with $500,000 in city funds, and the state of Illinois contributed $200,000. By late 1986, NHS had named a neighborhood director and had appointed a local board that included Salim Al Nurridin, a Roseland civic activist and native of Altgeld Gardens who had converted to Islam years earlier.

Early in 1987, with Alonzo Pruitt of St. George in the lead, six Roseland churches announced they were offering overnight shelter to any needy person on evenings when the temperature fell well below freezing. Also participating was Mission of Faith Baptist Church, whose pastor, Rev. Eugene Gibson, was president of the Roseland Clergy Association (RCA), and Fernwood United Methodist Church, whose pastor, Rev. Al Sampson, was a forty-eight-year-old veteran of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference whom King himself had ordained as a minister. Those three clergymen were taking the lead in protesting the lack of black professionals at a heavily patronized bank in Beverly, a largely white neighborhood immediately west of Washington Heights. They were also demanding youth employment opportunities at a large shopping plaza west of Beverly in Evergreen Park.

Pruitt, Gibson, and Sampson’s efforts received prominent coverage in the Defender, and sometime in early 1987 Obama got Gibson on the phone and won an invitation to the RCA’s next regular meeting. As Obama later told it, he made a brief presentation to the ten or so clergymen before someone else arrived late to the meeting. “A tall, pecan-colored man” with straightened hair “swept back in a pompadour,” wearing “a blue, double-breasted suit and a large gold cross across his scarlet tie” asked Barack whom he represented.

When Barack said DCP, the minister said that reminded him of a white man who had called on him many months before. “Funny-looking guy. Jewish name. You connected to the Catholics?” When Barack said yes, this person whom Obama called “Charles Smalls,” responded that “the last thing we need is to join up with a bunch of white money and Catholic churches and Jewish organizers to solve our problems … the archdiocese in this city is run by stone-cold racists. Always has been. White folks come in here thinking they know what’s best for us…. It’s all a political thing.” Smalls knew Obama meant well, but Barack wrote that he felt he was “roasting like a pig on a spit.”

Years later, a journalist named Al Sampson as the intolerant preacher, and Obama later confirmed that identification, explaining that he had just changed the appearance of the short, stout, and dark-skinned Sampson. Asked for the first time about the allegation, Sampson said he did not recall ever meeting Barack Obama in the late 1980s, but in a 2002 video interview Sampson had expressed his admiration for the notoriously bigoted Louis Farrakhan.

More than a quarter century later, Alonzo Pruitt still had a “vibrant memory” of that RCA meeting, with Barack wearing “an open-necked pale yellow shirt” and light brown dress shoes. Pruitt could picture Barack “carefully listening” and “responding with courtesy and restraint even when” others “did not practice courtesy and restraint. I was impressed that he was not defensive or hostile even when a reasonable person might choose the latter. At first I thought he was aloof, but as the meeting went on I realized that his getting angry would simply create a new issue with which to deal, and he was focused on what he perceived to be the heart of the matter.”

Obama received a dramatically warmer welcome when he visited Trinity United Church of Christ (TUCC) on 95th Street. Trinity was well known to every minister on the South Side because its pastor, Jeremiah A. Wright Jr., had grown his congregation from just eighty-seven members when he started there in 1972 to more than four thousand by the day Obama first visited. Almost two years earlier, Adrienne Jackson had tried unsuccessfully to interest Wright in DCP, and in Obama’s own later account, an aged “Reverend Philips” with a dying church first recommended he visit Wright. Yet among Chicago’s black preachers, an undocumented consensus would emerge that it was Rev. Lacey K. Curry, the dynamic pastor of Emmanuel Baptist, a vibrant church in the Auburn Gresham community north of DCP’s self-defined 95th Street boundary, who had told Barack to go see Wright.

But Wright would attest to much of Obama’s account of his first visit to Trinity, where Wright’s attractive secretary, Donita Powell Anderson, was at least as interested in the young gentleman caller as was her pastor. “She was smitten,” Wright smilingly remembered. In Barack’s telling, Wright’s first words to him were a humorous greeting: “Let’s see if Donita here will let me have a minute of your time.”

As of March 1987, forty-five-year-old Jerry Wright had already lived an eventful life. Raised by two well-educated parents in the Germantown neighborhood of northwest Philadelphia, Wright knew the black church from his earliest years because his father, Jeremiah Sr., was pastor of Grace Baptist Church. Years later, in a long interview, Wright would confess to misbehavior during his high school years—including an arrest for car theft—that was more serious than any of Obama’s indulgences while at Punahou. Jerry followed his father’s and mother’s footsteps and began college at Virginia Union University in Richmond before dropping out and enlisting in the marines. After two years, he changed uniforms and became a navy medical corpsman, ending up at Lyndon B. Johnson’s Bethesda bedside when the president underwent surgery in late 1966.

Upon leaving the service, Wright enrolled at Howard University to complete his undergraduate degree and also earn a master’s. Reconnecting to religious faith, Wright entered the University of Chicago Divinity School before becoming an assistant pastor at Beth Eden Baptist Church, in the Morgan Park neighborhood west of central Roseland. By late 1971, that affiliation had ended and Wright was searching for new employment when an older friend and mentor, Rev. Kenneth B. Smith, mentioned that the small congregation of Trinity UCC, where Smith had been the founding pastor in 1961, was searching for a new minister. Wright was interviewed by Vallmer Jordan, one of TUCC’s most dedicated members, and on March 1, 1972, Wright became Trinity’s pastor.

Wright inherited a small congregation and an annual budget of just $39,000, but the church had something almost equally valuable: a newly coined church slogan that declared Trinity as “unashamedly black and unapologetically Christian.” When the United Church of Christ created Trinity, it was aiming for a “high potential church” that would attract “the right kind of black people,” according to longtime Trinity member and staffer Julia M. Speller in her University of Chicago Ph.D. dissertation. “The class discrimination exhibited by the denomination” was stark, and soon after arriving at Trinity, Wright complained publicly that his new congregation had become “a citadel for the ultra-middle-class Negro.” He later quoted one founding member as confessing that “we could out-white white people,” and he also wrote that a “ ‘white church in a black face’ is exactly what we had become!”

Just two blocks east of Trinity were the Lowden Homes, where DCP’s Nadyne Griffin lived, and Wright later remembered that when he arrived at Trinity, “we first had to stop looking at the neighbors around the church as ‘those people.’ ” Within eight months, he had introduced a new youth choir, and not long after that, he told the senior choir to expand its repertoire to embrace gospel music. Those innovations caused almost two dozen of Trinity’s existing members to leave the church, and Jerry later wrote that “eighteen months into my pastorate … I felt as if I were a failure. It seemed to me as if everyone was leaving our church.”

But these changes brought in new members, and by 1977 Trinity’s congregation had grown to four hundred. In late 1978, the church moved into a new building with a seven-hundred-seat sanctuary, and in 1980, with Wright’s powerful sermons now being broadcast on the radio, Trinity’s membership began a rapid climb, reaching sixteen hundred by early 1981. The congregation included a number of prominent black Chicagoans, such as well-known Illinois appellate judge R. Eugene Pincham and Manford Byrd, like Val Jordan a charter member since 1961. In early 1981, when Byrd was passed over for promotion from deputy to superintendent of the Chicago Public Schools in favor of a black woman from California, Trinitarians were among the many black Chicagoans who vocally protested the denial of what Trinity called Byrd’s “earned ascension” in favor of an outsider. In response, Val Jordan and several others drafted a wide-ranging statement of values, modeled in part on the Ten Commandments, as a way of honoring Byrd at an August 9, 1981, ceremony. Trinity’s twelve-point “Black Value System” was notable for its powerful “disavowal of the pursuit of middleclassness” and an attendant warning against thinking “in terms of ‘we’ and ‘they’ ”—i.e., “those people”—“instead of ‘US’!”

By fall of 1982, Trinity had reached twenty-eight hundred members and its annual budget was now $700,000. In response, Wright and a trio of academically oriented members—Sokoni Karanja, Ayana Johnson-Karanja, and Iva E. Carruthers—drafted an almost two-hundred-page “compendium text for church-wide study.” Wright wrote an eleven-page statement of Trinity’s mission, beginning with a forceful call for “a conscious cutting across class and caste lines and so-called economic levels” and “utterly abandoning or rejecting the notion of the ‘middle class’ as the proper vineyard into which God has called us to labor.”

Wright also called out the usually unspoken dangers that “Black self-hatred” posed in African American communities, and he later recalled with some embarrassment how he had been entirely ignorant of the harm that youth gangs were doing in neighborhoods like Roseland until his eldest daughter Janet and her boyfriend were robbed at gunpoint in 1982 on Halsted Avenue, less than ten blocks from the Wrights’ home, by several Gangster Disciples. But perhaps equally daunting was how his daughter got her property returned, along with an apology, in just three hours after complaining to a next-door neighbor who knew who to call.

In that 1982 essay, Wright emphasized that Trinitarians “start from the cultural strengths already in existence within the Black tradition,” a view in keeping with John McKnight’s social capital emphasis. Throughout the decade, Trinity’s outreach ministries would grow along with the church, with a food co-op and a credit union being joined by a housing ministry that addressed the problem of foreclosed, boarded-up homes plus a high school counseling project and Saturday youth programs. “Educating constituents as to all the nuances and subtleties of the racist political system operative in Chicago,” Wright wrote, “is a very definite part of our ministry at Trinity.”

In 1983, Wright took a lead role, along with eight other black churchmen including Al Sampson, in fervently endorsing Harold Washington’s mayoral campaign. Borrowing Trinity’s own “unashamedly black and unapologetically Christian” slogan, the statement was supported by more than 250 members of the clergy. By 1986 Trinity had more than four thousand members, twenty-eight of whom were preparing for the ministry, and Wright was preaching at two separate Sunday services to cope with the growth. One charter member cited Wright’s “ability to call all his parishioners by their names, even as the church membership grew into the thousands,” as one more of his impressive gifts. Julia Speller wrote that by 1986 “a definite mission-consciousness began to emerge at Trinity,” and Jerry was pursuing a deepening interest in black Americans’ African cultural roots. Wright had been profoundly influenced by the pioneering black liberation theologian James H. Cone’s landmark 1969 book Black Theology and Black Power, although he strongly faulted Cone for calling African Americans “a people who were completely stripped of their African heritage.” Trinity, Wright wrote, “affirms our Africanness,” including “the premise that Christianity did not start in Europe. It started in Africa,” and “we affirm our African roots and use Africa as a starting point for understanding ourselves, understanding God, and understanding the world.” Indeed, “we understand Africa as the place where civilization began.”

By the time of Obama’s visit to Trinity in March 1987, word about Jeremiah Wright’s church had spread well beyond Chicago. A PBS Frontline television crew and well-known black journalist Roger Wilkins had just spent days at Trinity preparing an hour-long documentary on the church that would be nationally broadcast ten weeks later. “The rooms of Trinity are crammed full of its members all day, every day,” Wilkins told viewers while describing the church’s outreach ministries and Bible-study classes. “Trinity is one of the fastest growing and strongest black churches in America.”

Responding to Wilkins’s questions, Wright spoke colloquially and bluntly. For black teenagers in Roseland, Wright said, “You can’t be what you ain’t seen…. So many of our young boys haven’t seen nothing but the gangs and the pimps and the brothers on the corner,” and in their daily lives “they never have their horizons lifted.” But Wright also emphasized black Americans’ lack of self-esteem. “If I can somehow be white: a lot of black people have that feeling. If I can somehow be accepted. And Africa is a bad thing. I’m not African. I’m not African. I’m part Indian. I’m part Chinese. I’m part anything.”

That part of Wright’s worldview would resonate deeply with Barack, but his perspective on the breadth and depth of American racism matched that of Martin Luther King Jr. “How do we attack a system, get at systemic evil and realize that it’s not the individuals, it’s the system,” he told Wilkins. “You hate the sin and not the sinner.” Wilkins closed the telecast with a prophetic description of Trinity’s importance. “This church will be measured by how much of its power will reach beyond its own doors, and by how much its members will reach back, back to those left behind.” The day of the broadcast, the Sun-Times told Chicagoans not to miss “a compelling and moving portrait of one Chicago clergyman who has made a difference.” Jeremiah Wright “sets a standard of excellence that should inspire clergy of all faiths.”

“The first time I walked into Trinity, I felt at home,” Barack later told Wright’s daughter Janet. Furthermore, Obama recalled, “there was an explicitly political aspect to the mission and message of Trinity at that time that I found appealing.” In their first 1987 conversation, Barack tried to sell Wright on DCP’s program. “He came with this Saul Alinsky community organizing vision,” Wright recounted years later. “He was interested in organizing churches,” yet Barack’s depth of knowledge about the black church was woeful indeed. “He didn’t know who J. H. Jackson was,” Wright remembered, naming the conservative, dictatorial president of the National Baptist Convention who pastored Chicago’s Olivet Baptist Church and was infamous for changing Olivet’s address from 3101 South Parkway to 405 East 31st Street when Parkway was renamed Martin Luther King Drive.

Wright remembers that Obama “had this wild-eyed idealistic exciting plan” of “organizing pastors and churches” all across Roseland in support of his Career Education Network. “I looked at him and I said, ‘Do you know what Joseph’s brother said when they saw him coming across the field?” Obama, utterly unfamiliar with the Bible, said no. “They said ‘Behold the dreamer.’ You’re dreaming. This is not going to happen,” Wright told him. “You’re in a minefield you have no concept about whatsoever in terms of trying to get us all to work together, even on something as important as the educational issues in the Roseland community,” Wright explained, citing the twin evils of denominational divides and local Chicago politics.

Given Wright’s busy schedule, that first conversation ended after an hour. But Obama soon returned, talking first with Donita before sitting down with Wright, who remembers he had “questions about this unknown entity, the black church, and its theology…. I had studied Islam in West Africa, and he wanted to know about that.” In addition, “we talked about the difference between theological investigation, rabbinic study, and personal faith, personal beliefs, and how I separated those two,” Wright recalled. “Our visits became more of that nature and that level than the community organizing piece, because I said, ‘That ain’t going to happen. If you mention my name, I can tell you preachers who are not coming in the Roseland area.’ ” That surprised Obama, and Wright also spoke about the black church’s “rabid anti-Catholic” sentiment. “We would spend time talking about religious stuff like that to help him understand that brick wall he’s running up against in terms of organizing churches.” So “most of the time … we talked about how insane” religious antipathies could be, “more so than community organizing.”

Barack continued to visit Wright in the months ahead, and their conversations gave Obama a greater understanding of why almost all of the people with whom he was working held their religious faith as a source of strength that could give them courage. It not only “bolstered them against heartache and disappointment” but could be “an active, palpable agent in the world,” undergirding their involvement by offering “a source of hope.” Witnessing that, Barack remembered, “moved me deeply” and “made me recognize that many of the impulses that … were propelling me forward were the same impulses that express themselves through the church.”

Obama was even more warmly welcomed by Father Michael Pfleger at St. Sabina Roman Catholic Church in the Gresham neighborhood, well above DCP’s northern boundary. The thirty-eight-year-old Pfleger had been a seminary classmate of Holy Rosary’s Bill Stenzel, had first met Jerry Wright five years earlier in an Ashland Avenue barber shop, and was well acquainted with Deacon Tommy West, the energetic DCP member from St. Catherine’s who spent more time at St. Sabina than at his home church. Pfleger had grown up barely a mile west of St. Sabina on Chicago’s Southwest Side, and in 1966, at age seventeen, he had watched as an angry white mob attacked an open-housing march being led by Martin Luther King Jr. in Marquette Park, just a few blocks north. By 1987 Pfleger had been at St. Sabina for twelve years, and although his congregation was nowhere near the size of Trinity’s, no church in Chicago, and certainly not one with a white priest, offered as vibrant a Sunday service as Mike Pfleger did.

Years later, Pfleger recalled that Obama “came in and introduced himself and what he was doing.” He spoke about how churches “were the most powerful tool in the community for social justice and for equality” and how they should be actively pursuing those goals, not watching from the sidelines. “I was amazed by his brilliance,” Pfleger recalled; he was struck as well by “his aggressiveness.” Pfleger asked Barack “what was his church,” because “people that want to work with churches ought to be in a church.” Barack replied that “he was still looking, had been visiting some places, Trinity being one of them.” Pfleger had expected a twenty-minute conversation, “and it went much longer.” He offered Obama his full support, and after Barack left, Pfleger could remember “walking out of this room saying, ‘That’s somebody to be watched. He’s going places.’ ”

For Obama, these early months of 1987 were intense as he expanded his horizons and added to his growing set of influential acquaintances. On March 2, in faraway Jakarta, Lolo Soetoro died of liver disease at age fifty-two. If Ann called Barack with the news—“they did not talk often,” Sheila recalled—he did not mention it to her or anyone else. He also “never talked that much about his dad” or his death to Sheila, and as best she could tell, “Barack’s father played virtually no emotional role in Barack’s life.” He continued his weekly conversations with Greg Galluzzo—an hour on March 4, ninety minutes each on March 13 and 20, another hour on March 24—and he also introduced his good friend Johnnie Owens to Galluzzo.

Barack and Johnnie had begun discussing whether Johnnie would leave Friends of the Parks and join Barack at DCP, but Owens needed a salary much like Barack’s $20,000, and that meant Barack would have to add the MacArthur Foundation as a funder in addition to CHD, Woods, and Wieboldt.

By mid-March, Barack’s most pressing concern was on the jobs front, and on Monday, March 23—just two weeks before Election Day—Mayor Washington was coming to Roseland to open the much-delayed new Far South Side jobs center that his employment deputy Maria Cerda had agreed to establish more than six months earlier. In the run-up to that ceremony, Barack dealt extensively with Salim Al Nurridin, a politically sophisticated Roseland figure whose Roseland Community Development Corporation (RCDC) was relatively low profile but whose long-standing acquaintance with one of Barack’s new mentors allowed for an easy introduction to this young organizer who was “under the tutelage of Al Raby.”