По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

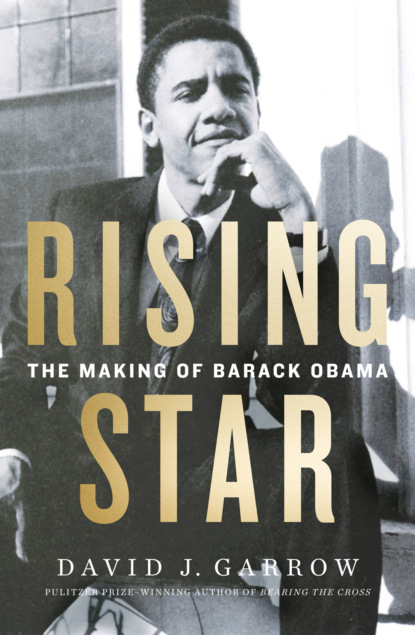

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When the final exam for that Russian 101 course took place on January 28, 1961, Ann Dunham as well as her parents knew she was almost three months pregnant. According to later documents—no contemporary one has ever been located—on Thursday, February 2, 1961, Ann and Barack took a brief interisland flight from Honolulu to Maui and were married in the small county seat of Wailuku, with no relatives or friends present. Obama’s closest confidante, his younger sister Zeituni Onyango, recounted her older brother’s version of what had occurred: “the father of Ann said that they have to marry.” Stanley Dunham insisted that his pregnant daughter get married rather than give birth to a bastard. But why did they go to the time and expense of flying from Honolulu to Maui? Stanley and Madelyn likely did not want any potentially embarrassing questions arising at either Isle-Wide furniture or at the Bank of Hawaii, where Madelyn had been hired as an escrow officer. They knew that marriages on Oahu were regularly listed in both of Honolulu’s daily newspapers, but ones occurring in the outer islands were not.

Ann Dunham Obama did not register for spring classes at the University of Hawaii. In contrast, Obama was honored with a Phi Kappa Phi certificate for his freshman-year grade point average and then a few weeks later was named to the Dean’s List because of his fall 1960 GPA. A young English professor, writing to AAI in support of Obama’s request for scholarship assistance for his sophomore year, reported that “Obama has done an exemplary job of getting along with people” and called him “a genuinely enlightened twentieth-century man.” Obama’s friends Neil Abercrombie and Andy Zane were leading local racial equality efforts, and when a national governors’ conference brought outspoken segregationist governor John Patterson of Alabama to Honolulu in June 1961, he was greeted at the airport by about two dozen picketers holding signs proclaiming “Welcome to the Land of Miscegenation.” The lone black participant certainly represented the truth of that slogan, and he told a reporter that “Hawaii gives them an example where races live together,” but he asked “not to be identified” other than as a UH student.

But in that student’s own personal context, the races actually did not live together. During her pregnancy, Ann continued to reside with her parents at 6085 Kalanianaole Highway, and Obama remained in his apartment on Punahou Street. When UH’s foreign-student adviser, Mrs. Sumie McCabe, learned of Obama’s new marriage some two months after it occurred, she immediately called the Honolulu office of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service to tell the INS about his changed circumstances. INS agent Lyle Dahlin memorialized McCabe’s call in a memo that went into Obama’s file, noting that “the problem is that when he arrived in the U.S. the subject had a wife in Kenya.” McCabe said Obama “is very intelligent,” but he “has been running around with several girls since he first arrived here and last summer she cautioned him about his playboy ways. Subject replied that he would ‘try’ to stay away from the girls. Subject got his USC [U.S. citizen] wife ‘Hapei’ and although they were married, they do not live together, and Miss Dunham is making arrangements with the Salvation Army to give the baby away. Subject told Mrs. McCabe that in Kenya all that is necessary to be divorced is to tell the wife that she is divorced and that constitutes a legal divorce. Subject claims to have been divorced from his wife in Kenya in this method.”

The INS was powerless to take any action absent a criminal conviction for bigamy, but Dahlin recommended that Obama be “closely questioned” before he was approved for another extension of his student residency visa and that “denial be considered.” If Ann were to petition on his behalf, “make sure an investigation is conducted as to the bona-fide[s] of the marriage.” Subsequent documents in Obama’s own hand would soon demonstrate that he in no way really considered himself divorced from Kezia. He had grown up in a family and ethnic culture where multiple wives were the norm, and he was not telling the truth about that to McCabe. There are no documents or anyone’s recollections to support Obama’s claim that Ann Dunham intended to give birth to their child and then put it up for adoption. Obama’s closest relative, his sister Zeituni, dismissed the possibility out of hand when the memo first came to light decades later: “no African especially in Kenya would think of giving his child away.”

So when Dr. David A. Sinclair delivered Barack Hussein Obama II at 7:24 P.M. on Friday, August 4, 1961, at Kapiolani Maternity & Gynecological Hospital on Punahou Street, just three blocks south from where the child had been conceived, the Salvation Army was not called. Instead, Madelyn and Stan each called their siblings with the news. Madelyn’s younger brother Charles recounted her description of the new baby: “He’s not black like his father, he’s not white. More like coffee with cream.” Ralph Dunham remembered Stan calling him from the hospital and Madelyn getting on the phone too. Stan’s younger sister Virginia Dunham Goeldner recalled him phoning her too and, fifty years later, expressed astonishment that some of her longtime neighbors in Maumelle, Arkansas, doubted the fact of her grandnephew’s birth. “Why did Stanley call and say he was born and why were they over at the hospital? Why did he bother to call” on that Friday night?

The birth occurred exactly two years to the day, and indeed almost exactly to the hour, since Barack Hussein Obama had boarded his flight at Nairobi Embakasi. On Monday, Ann Dunham Obama signed her son’s Hawaii State Department of Health birth certificate, and it was signed on Tuesday by Dr. Sinclair and the local registrar of births. Five days later, on August 13, the Honolulu Advertiser’s listing of “Births, Marriages, Deaths” on page B6 included in the first category “Mr. and Mrs. Barack H. Obama, 6085 Kalanianaole Hwy., son, Aug. 4.” The next day’s Honolulu Star-Bulletin carried the same listing on page 24, with copy editors at that paper spelling out “Highway” and “August” in full. The birth certificate only contained the address for “Usual Residence of Mother”; there was no request for an address following “Full Name of Father,” so the newspapers presumed that the newborn’s parents lived together.

Less than four weeks after his son’s birth, Barack Hussein Obama applied for and quickly received a routine one-year extension of his student residency visa. Lee Zeigler, newly arrived from Stanford University, had replaced Sumie McCabe as UH’s foreign student adviser, and a different INS agent, William T. Wood II, not Lyle Dahlin, reviewed and approved Obama’s application. Obama said he had received $1,000 in scholarship support via the African-American Institute, but again requested to work for up to twenty-five hours a week to meet the balance of his expenses. He also indicated that sometime subsequent to March 1961 he had moved from Punahou Street to 1482 Alencastre Street, well east of UH’s campus. Barack listed Ann S. Dunham as his spouse, and Agent Wood’s summary memo noted, “They have one child born Honolulu on 8/4/61—Barack Obama II, child living with mother (she lives with her parents & subject lives at 1482 Alencastre St.).” But Wood noted something else too: “U.S.C. spouse to go to Wash. State University next semester.”

Sometime soon after Wood wrote that memo, Ann and her weeks-old son flew from Honolulu to Seattle: not so she could attend WSU, in far southeastern Washington State, but to enroll at her beloved UDub, which she had wanted to attend a year earlier. Ann and baby Barack stayed briefly with a family friend on Mercer Island before settling into an apartment at 516 Thirteenth Avenue East in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, well south of the university. According to her UDub transcript, she registered for two evening courses, Anthropology 100: Introduction to the Study of Man and Political Science 201: Modern Government. Classes began in late September.

But why did Ann Dunham Obama take her newborn and leave her husband, parents, and Honolulu for the familiar confines of Seattle? She clearly preferred UDub and its environs over UH, but she told half a dozen old high school friends, as well as a woman who also lived at 516 Thirteenth Avenue East and babysat young Barack while Ann attended classes, that she loved her husband. But the young couple never chose to live together at any time following the onset of Ann’s pregnancy, and Ann relocated herself a long airplane flight away as soon as her son was old enough to travel. None of the direct participants—Ann, Obama, Madelyn, and Stan—ever offered a clear explanation that has survived in anyone’s recollections a half century later.

Obama had taken to calling his son’s mother Anna, not Ann, and she seems to have adopted this as well, according to both the 1961–62 Polk City Directory for Seattle, which lists “Obama Anna Mrs. studt” and her neighboring babysitter, Alaskan native Mary Toutonghi, who also remembered her as Anna. Ann did well in her fall courses, earning an A in anthropology and a B in political science; she did even better in the winter term that ran from late December 1961 through mid-March 1962, getting As in both Philosophy 120: Introduction to Logic and, interestingly, History 478: History of Southern Africa. Mary Toutonghi babysat regularly during those months on the evenings Ann attended classes, and years later she would recall infant Barack as “very curious and very alert,” “very happy and a good size.” In March Ann enrolled in three regular daytime courses, obtaining Bs in Chinese Civilization and History of Modern Philosophy but changing English Political and Social History to just an audit.

With Ann in Seattle, Obama launched into his senior year at UH. Only Neil Abercrombie was aware of Obama’s relationship with Dunham or that he had fathered a child in Honolulu. One new graduate student, Robert Ruenitz, would later admit that “for any of us to say that we knew Obama well would be difficult. He was a private man with academic achievement his foremost goal.” Another 1961 grad student, Cambodia native Naranhkiri Tith, debated nuclear arms with Obama at a widely publicized campus symposium. Obama labeled the issue not a “balance of power” but a “balance of terror” and asserted that most U.S. foreign aid took the form of weapons and other military assistance. Tith and other graduate students also partied regularly with Obama, who “loved to drink” to the point of becoming “totally drunk” at repeated parties. “He also was a womanizer,” Tith recounted years later.

Even so, Obama’s academic success continued apace. In mid-January he addressed the NAACP’s Honolulu branch on “Changes in Africa Today,” and in early February, he was featured prominently in a “Dear Friend” fund-raising appeal distributed by Bill Scheinman and Tom Mboya’s African-American Students Foundation. Sent in the name of Ruth Bunche, whose diplomat husband Ralph in 1950 had been the first African American ever to win the Nobel Peace Prize, the letter briefly profiled two young men “of whom we are especially proud” out of more than five hundred African students who were then studying in the U.S. One was completing a graduate degree in engineering at Columbia University; the other was Obama, “an honor student of the University of Hawaii where he will complete a four year course in three years.” The letter predicted Obama would soon qualify for the national academic honor society, Phi Beta Kappa, and in late April he was elected to membership.

With graduation only a month away, Obama was also a featured speaker at a large Mother’s Day event organized by the Hawaii Peace Rally Committee to oppose nuclear weapons. The afternoon event drew hundreds to Ala Moana Beach Park. Liberal Democratic state legislators Tom Gill and Patsy Mink were joined on the speakers’ platform by four clergymen and several UH professors. The crowd included powerful International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) director Jack Hall, and conservative counterprotesters from the Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) who waved signs advocating continued U.S. nuclear weapons testing.

Speaking to the crowd, Obama denounced “foreign aid which is directed toward military conquest or the acquisition of bases.” Speaking as an African, “anything which relieves military spending will help us,” and if peace were to replace nuclear confrontation, “we will be able to receive your aid with an open mind and without suspicion.”

In early May 1962, Betty Mooney Kirk, who had married and relocated to her husband’s hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, wrote to Tom Mboya in Nairobi to seek his help in finding someone to sponsor Obama for graduate school, “preferably at Harvard.” She enclosed a copy of Barack’s résumé, which she had prepared, and it stated that Obama already had applied to and been accepted for graduate study at Harvard, Yale, the University of Michigan, and the University of California at Berkeley. Harvard alone had offered financial aid, in the limited amount of $1,500, but Betty hoped Tom could find further assistance because Barack “has the opportunity and the brains.” Mboya replied with congratulations, but according to Betty was “not very hopeful” about locating available funding.

Betty’s colleague Helen Roberts was back in Nairobi, and, perhaps at Betty’s urging, was actively assisting Kezia Obama, now the single mother of two young children—Rita Auma had been born in early 1960, six months after her father’s departure for the U.S. Kezia was sometimes in Kogelo with her two children and Barack’s father and stepmother Sarah, sometimes with her parents in Kendu Bay, and other times staying with her brother Wilson Odiawo in Nairobi. Roberts helped Kezia take some educational courses, and told one friend that Kezia “is very anxious to be a suitable wife for Barack when he returns.” Roberts remarked, “I think Barack will notice quite a difference in her when he at last returns.”

In late May 1962, Obama wrote to Mboya and apologized for not having written in a long time. He bragged about his academic achievements at UH, falsely claiming to have already earned an M.A. degree in addition to his impressive three-year B.A. and a 3.6 GPA. Reciting his Phi Beta Kappa and Phi Kappa Phi honors as well as an Omicron Delta Kappa award, he told Mboya—twice, in almost identical sentences—that these were “the highest academic honours that anyone can get in the U.S.A. for high academic attainments.” What’s more, he was about to leave for Harvard, “where I have been offered a fellowship for my Ph.D. I intend to take at least two years working on my Ph.D. and at most three years. Then I will be coming home.” Obama closed by telling Mboya, “I have enjoyed my stay here, but I will be accelerating my coming home as much as I can. You know my wife is in Nairobi there, and I would really appreciate any help you may give her.”

His letter to Mboya did not mention his second wife or third child, nor did he ever say anything about them to Helen Roberts or to the hugely supportive Betty Mooney Kirk. As his eldest son would ruefully put it years later, by the end of his time in Hawaii “Barack’s life was now a series of compartments.” On June 17, 1962, Obama received his B.A. degree—and not any M.A.—at UH’s commencement. Three days later the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, in an article headlined “Kenya Student Wins Fellowship,” reported how the “straight A” economics major was headed to Harvard to obtain his Ph.D. “He plans to return to Africa and work in development of underdeveloped areas and international trade at the planning and policy-making level,” the story explained. “He leaves next week for a tour of mainland universities,” beginning in California, prior to entering Harvard.

In Seattle, Ann’s spring quarter classes had concluded, and her high school friend Barbara Cannon Rusk, who had moved to Utah after graduating, “came back to Seattle in the summer of 1962.” One day, Rusk stopped by Ann’s apartment on Capitol Hill. Her initial visit “was after June, and could have been as late as September. I visited her a couple of times,” she recalled more than forty years later. “She wasn’t in classes, and didn’t have a job. I recall her being melancholy…. I had a sense that something wasn’t right in her marriage. It was all very mysterious,” as her husband was already headed to Harvard. “I didn’t ask her about the relationship.”

Also years later, another young woman whose Mercer Island family had known the Dunhams very well, Judy Farner Ware, would recount to Janny Scott, Ann’s biographer, a distinct memory of meeting Ann and Obama in what she recalled was Port Angeles, Washington—the ferry port at the top of western Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula, just across the Strait of Juan de Fuca from Victoria, British Columbia. She remembered the meeting because an openly flirtatious Obama all but hit on her. Had Obama traveled north from San Francisco to see his second wife and second son in Seattle, and then perhaps they toured the region? Ann didn’t own a car or know how to drive, and neither Ann nor Obama ever mentioned such a visit to anyone in later years.

Ann and her son were still in Seattle when Obama left Honolulu for the mainland. Perhaps it should be presumed that Obama did set eyes on his newborn son back in August 1961 before Ann and the baby left for Seattle—though no one’s surviving accounts say that did occur—but unless Obama made some equally unrecorded, unremembered visit to Seattle before heading eastward, he would not have seen his son for years to come. In truth, as one scholar would acutely put it, Barack Hussein Obama was only “a sperm donor in his son’s life.”

Almost three decades later, his eldest daughter would meet Ann Dunham and ask her what had happened between her and her father. Ann’s story then was that Obama had asked her to join him at Harvard, but “she had not wanted to go. She had loved him, but she had feared having to give up too much of herself.”

By mid-July 1962, Obama had gotten as far east as Oklahoma, where he stopped in Tulsa to visit Betty Mooney Kirk and her husband. By no later than August 17, he was in Baltimore, at the Koinonia Foundation’s campus, where he had stayed exactly three years earlier. While there, he updated his immigration papers, telling the INS his study at Harvard would be supported by $1,000 each from Frank Laubach’s Literacy Fund and the Phelps Stokes Fund, in addition to his university fellowship. On his “Application to Extend Time of Temporary Stay,” Obama listed himself as married, but under children entered only one name: “Roy Obama.”

By September, Obama had arrived at Harvard, and Ann and her now one-year-old son had returned to Honolulu. Stan and Madelyn had moved from Kalanianaole Highway to an apartment on Alexander Street, but Ann and young Barack initially stayed at 2277 Kamehameha Avenue, close to UH. Ann sat out the fall semester, but in January 1963, she resumed taking classes as a sophomore. Sometime prior to the end of 1963, Stan and Madelyn relocated to a house at 2234 University Avenue, and Ann and her son soon moved in with her parents.

As Ann adapted to a heavier academic load, and Madelyn worked long days at her bank job, young Barack spent most of his time with his fit and youthful forty-five-year-old grandfather. Obama Sr.’s old friend Neil Abercrombie, still a graduate student at UH, saw Stan and young Barry—as his grandparents called him—around town during Barry’s childhood. “His grandfather was the most wonderful guy” and it was readily apparent that “Stanley loved that little boy,” Abercrombie remembered. “He took him everywhere,” including to an arrival ceremony for two Gemini astronauts who had splashed down safely in the Pacific after an aborted space flight. Barack would “remember sitting on my grandfather’s shoulders” at Hickam Air Force Base and “dreaming of where they had been.” Abercombie recalled: “In the absence of his father, there was not a kinder, more understanding man than Stanley Dunham. He was loving and generous.”

Indeed, among the dozens of photos of young Barry from his childhood, it is impossible to find one where he is not smiling broadly. Stan’s boss’s daughter, Cindy Pratt Holtz, remembers Stanley bringing Barry with him to the Pratt furniture warehouse. Young Obama was “so full of life, a twinkle in the eye, giggling all the time.” In the fall of 1966, five-year-old Barry began kindergarten at nearby Noelani Elementary School, and Aimee Yatsushiro, one of his two teachers, remembers him similarly: “always smiling—had a perpetual smile.” Obama later said, “My earliest memory is running around in a backyard gathering up mangoes that had fallen in our backyard when I was five” or perhaps four. “A lot of my early memories,” he added, are “of an almost idyllic sort of early childhood in Hawaii.”

In the meantime, his barely twenty-one-year-old mother had found new happiness in tandem with her studies. “Lolo” Soetoro—officially Soetoro Martodihardjo, after his Javanese father’s name—first arrived in Honolulu from Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in September 1962 as a twenty-seven-year-old graduate student in geography. After his first year of classes, Soetoro spent the summer of 1963 at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, but that fall he returned to UH for the final year of his two-year master’s program. He and Ann met each other sometime during those months. One mutual friend recalled that “he had a good sense of humor, and he loved to party.” Ann would later remark how attractive Lolo was in tennis shorts. “She liked brown bums,” her most outspoken friend would tell biographer Janny Scott, and by early 1964, Ann and Lolo were a public couple. Seemingly because of this new romance, on January 20, 1964, Stanley Ann Dunham Obama signed a “Libel for Divorce,” as Hawaii legal process termed the form, and five days later the complaint was officially filed in Honolulu circuit court. A copy was addressed to Barack H. Obama in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Obama had been at Harvard for almost eighteen months. He was one of thirty-five newly admitted doctoral students in the Department of Economics, and in a December 1962 letter to a friend in Hawaii, Obama confessed that “the competition here is just maddening.” The heavy reading load made every week “pretty rough,” and while “I find Harvard a very stimulating place at least intellectually,” his focus was “my own research on the theory I am trying to build.” He added, “I will stay here at least for two years to three years depending on when I am able to finish my dissertation,” but after he received a C+ and two Bs in his first semester, Harvard refused to renew his fellowship to cover his second year of classes. Two senior economists nonetheless praised Obama’s “intelligence, initiative, and diligence,” and thanks once again to Betty Mooney Kirk and the African-American Institute, external funding allowed him to continue.

Barack first lived at 49 Irving Street before moving into a top-floor apartment at 170 Magazine Street with a Nigerian fellow, one of about eighty African students at Harvard—a vast change from his unique status in Honolulu. Obama actively mentored younger Kenyan students from around greater Boston; George Saitoti, who was eighteen years old when he knew Obama, told biographer Sally Jacobs “we looked upon him as a model. He really gave us inspiration.” In the fall of 1963, Obama’s brother Omar Onyango, a decade younger, arrived in Boston to attend the posh Browne & Nichols School, just west of Harvard, thanks to his older brother’s social acquaintance with a young woman whose father was the school’s treasurer.

That same young woman, like a number of Obama’s African friends in Cambridge, also witnessed a continuation—and perhaps an intensification—of the heavy drinking and heavy-handed pursuit of women that had marked Barack’s three years at UH. “He’d dance in a very suggestive way, no subtlety,” that female friend recounted to Sally Jacobs. “He used suggestive, provocative language, I would say overly sexual…. It was kind of a God’s gift to women thing.” One Nigerian friend recalled telling a drunken Obama to leave a young woman alone, and an African undergraduate woman told Jacobs about consoling a fellow female undergraduate who had been an Obama girlfriend until she learned he was already married, presumably to Kezia.

In late January 1964, Rev. Dana Klotzle, who oversaw the Unitarian Universalist Association’s (UUA) sponsorship of about a dozen East African students who, like Omar, were attending secondary schools around Boston, notified the local INS office of a troubling development. A young Kenyan woman who was attending school in Auburndale, Massachusetts, had suddenly flown to London on January 10 on a round-trip ticket. UUA had terminated her sponsorship and would not accept her back; an INS agent phoned the school for additional information. The dean of women said the girl had claimed she was visiting a sick sister, but there was no evidence of a sister in Britain. What’s more, she had been “receiving advice from another student from Kenya, one Obama who is likely her boy friend and who is at Harvard.” The Unitarians suspected she had flown to London to obtain an abortion. Obama had been phoning the school seeking her reinstatement and also had called a second school, which refused to accept her. Rev. Klotzle, the memo reported, thought Obama was “a slippery character.” The Boston INS office then notified the U.S. consul in London of the girl’s flight and Obama’s involvement.

In Hawaii, on March 5, Judge Samuel P. King held a brief hearing on Ann’s divorce petition; fifteen days later, he signed a “Decree of Divorce.” Ann was “granted the care, custody and control of Barack Hussein Obama, II,” with Obama Sr. having “the right of reasonable visitation.” Pursuant to Ann’s request, “the question of child support is specifically reserved until raised hereafter.” As with Ann’s initial complaint, a copy was mailed to Obama in Cambridge.

Four weeks later, Obama visited the Boston INS office to extend his student residency visa for another year. For the new application, Harvard certified that “Mr. Obama expects to be registered as a full-time student during the academic year 1964–65,” but the INS agent reviewing the file noted the January contretemps and a supervisor instructed him to “hold up extension for present.” The agent made several calls to Harvard, in part because Obama had left blank both the marital line and the one about employment, stating there that he could not remember where he had worked in the U.S. The agent noted: “Harvard thinks he’s married to someone in Kenya and someone in Honolulu, but that possibly he belongs to a tribe where multiple marriages are O.K.” Obama’s doctoral qualifying exams were soon approaching, and the director of Harvard’s international students office wanted to hold off on questioning Obama until those were finished.

Obama was aware of the inquiries, and he called the INS to say he now remembered working at the Institute of International Marketing in Cambridge during the summer of 1963. Harvard officials told the INS that Obama might also be married to someone in Cambridge, and in mid-May David Henry, director of Harvard’s international students office, called INS agent M. F. McKeon to say he had conferred with both a graduate school dean and the chairman of Harvard’s Economics Department.

“Obama has passed his general exams, which indicates that on academic grounds, he is entitled to stay around here and write his thesis,” McKeon wrote in a memo memorializing the phone conversation. “However, they are going to try to cook something up to ease him out. All three will have to agree on this, however. They are planning on telling him that they will not give him any money, and that he had better return to Kenya and prepare his thesis at home.” That would take several weeks, but “at this time Harvard does not plan on having Obama registered as a full-time student during the academic year 1964–1965 as stated on” Obama’s application a month earlier.

On May 27, 1964, Harvard’s David Henry sent Obama a life-changing letter. It began by acknowledging that Obama had completed his course work and that only his thesis remained to be completed before he could get his Ph.D. But the letter also said that neither the Department of Economics nor the graduate school had the funds to support him in Cambridge. It then said, “We have, therefore, come to the conclusion that you should terminate your stay in the United States and return to Kenya to carry on your research and the writing of your thesis.” He was given until June 19—which was hardly three weeks away!—to arrange for his departure. Henry indicated that copies of the letter were going to graduate school associate dean Reginald H. Phelps, a historian of modern Germany, and Economics Department chairman John T. Dunlop, a distinguished professor who would go on to become dean of Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and then U.S. secretary of labor.

Unspoken in Henry’s letter—though crystal clear in Obama’s INS file—was Harvard’s unwillingness to continue hosting a man whose sexual energies, whether inter-African or serially miscegenous, would not be tolerated in tony Cambridge as they had been in multihued Honolulu. Two weeks later an INS form letter instructed Obama that he had until July 8, instead of June 19, to depart the United States. On June 18, an understandably agitated Obama phoned the Boston INS office and insisted that he be given specific grounds for why his residency extension was being denied. An INS agent emphasized that the decision was final, but Obama called again the next day and asked to speak to the district director, who refused to take the call. Obama declared he lacked funds to leave the U.S., and the next day he asked a Harvard secretary to call the INS on his behalf. She too was told INS’s ruling was final. At that point, Obama apparently gave up; on Monday, July 6, 1964, he departed from New York’s newly renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport bound for Paris and then Nairobi, which, as of seven months earlier, was now the capital of newly independent Kenya.

On the other side of the United States, Ann Dunham and Lolo Soetoro were married on Monday, March 15, 1965, on Molokai, a smaller Hawaiian isle southeast of Oahu. Neither Ann’s son nor her parents attended the ceremony, which took place only three months before Lolo’s current residency visa would expire. He had received his M.A. in geography in June 1964, but a month later both UH and the INS approved another one-year residency during which he could get practical experience working for local engineering and surveying firms.

INS documents indicate that Ann and Barry never moved to 3326 Oahu Avenue, where Lolo was living, but instead remained at 2234 University Avenue with Stan and Madelyn. The looming question of whether Lolo would be able to remain in the U.S. beyond June soon brought both him and Ann into extensive contacts with the INS that mirrored what her ex-spouse had experienced a year earlier.

Sometime during May or June 1965, UH’s East-West Center (EWC), which had sponsored Lolo’s graduate study, received a cable from the Indonesian embassy in Washington requesting Soetoro’s immediate return to Jakarta. But Lolo and Ann had already taken the initiative to win an extension of his visa, and following two joint interviews at the Honolulu INS office, on June 7 Lolo’s residency permit was extended until mid-June 1966. On July 2, when Lolo informed the EWC of that, he was summoned to a July 6 meeting to be reminded “that the East-West Center still retained visa sponsorship and authority” regarding his residency. Lolo said he had sought the extension because his wife was suffering from a stomach ailment that might require surgery, but later that day EWC phoned INS, which immediately summoned both Lolo and Ann to another interview on July 19. In the interim, Ann, using Dunham as her surname, applied for and received her first U.S. passport.

Officials from the EWC visited the Honolulu INS office to explain that their agreement with the Indonesian government required that “every effort will be made to return students at the completion of their grants.” Thus EWC “shall appreciate any effort which you can make to insure that Mr. Soetoro will be returned to Indonesia as soon as possible.”

Before the July 19 session, Lolo submitted a statement to the Honolulu INS office noting that in his homeland “anti-American feeling has reached a feverish pitch under the direction of the Indonesian communist party.” This was supported by widespread U.S. press reports. Lolo asserted, “I have been advised by both family and friends in Indonesia that it would be dangerous to endeavor to return with my wife at the present time.” In addition, “I would meet with much prejudice myself in seeking employment” because of his U.S. educational background, and “land belonging to my family has already been confiscated by the government as part of a communistic land reform plan,” a policy that press reports again corroborated. Citing his “former compulsory association with the Indonesian army while still a student,” Lolo also feared being dragooned into battlefield service in Indonesia’s armed conflict with Malaysia if he returned home.

Soon after the July 19 interview, INS Honolulu recommended denial of any ongoing residency for Lolo. But almost two months later, the EWC notified Indonesia’s San Francisco consulate that Lolo would return to Indonesia in June 1966—and his wife would accompany him. This was just days before Indonesia was plunged into months of bloody, widespread violence in which hundreds of thousands of the previously ascendant Communists and perceived sympathizers were slaughtered by the Indonesian army and allied militias. That turmoil commenced with an unsuccessful, Communist-backed revolt against the army leadership by a small band of junior officers on September 30, 1965.

For the next six months, the violently anti-Communist army leadership took firm control of the country and a half million or more civilians were killed. Even with knowledge of the tumult, Ann, on November 30, gave the INS an affidavit acknowledging, “I don’t feel that I would undergo any exceptional hardship if my husband were to depart from the United [States] to reside abroad as the regulations require.” Those rules would allow Lolo’s readmission, as her husband, after two years’ absence from the U.S., a preferable course to being hamstrung by EWC’s deference to Indonesian authorities.

If the elimination of the anti-American Communist presence in Indonesia is what caused Lolo and Ann to change their strategy, that has gone unrecorded. Ann’s affidavit did, however, say she was “living with my parents in the home which they rent” and that “my son by a former marriage lives there with us.” INS’s efforts to revoke Lolo’s existing extension petered out, and on June 20, 1966—the last possible day—Lolo Soetoro flew out of Honolulu bound for Jakarta.

After Lolo’s departure, Ann took a secretarial job in UH’s student government office and also began doing some temporary nighttime tutoring and paper grading. That gave her an income of about $400 per month, and she told INS officials she hoped to save enough money to join Lolo in Indonesia in summer 1967. “We figure on going and staying until my husband’s time is up and then come back together.” With young Barry in kindergarten at Noelani Elementary School, and Stan and Madelyn both working full-time, Ann spent $50 to $75 a month for a babysitter on weekdays from 2:30 P.M. to 5:00 P.M. In December 1966, she told INS that she expected to complete her B.A. degree in anthropology in August 1967 and would join Lolo in Indonesia that October. She was already attempting to secure employment at the U.S. embassy in Jakarta.

INS did not appear open to waiving the two-years-abroad requirement for Lolo, and in May 1967 INS agent Robert Schultz phoned Ann for an update. “She and her child will definitely go to Indonesia to join her husband if he is not permitted to return to the United States sometime in the near future, as she is no longer able to endure the separation,” Schultz noted. “Her son is now in kindergarten and will commence the first grade next September and if it is necessary for her and the child to go to Indonesia, she will educate the child at home with the help of school texts from the U.S. as approved by the Board of Education in Honolulu.” Unbeknownst to Ann, this description of young Barry’s educational plight would set in motion a change in the INS’s attitude about a waiver. Still, in late June, she applied to amend her 1965 passport, taking Soetoro rather than Dunham as her surname.

In August 1967, just as Ann was receiving her B.A. from UH, INS, layer by bureaucratic layer, gradually agreed to grant Lolo a waiver, and two months later notified the State Department of that intent. Nine months would then pass before the Honolulu INS office realized that State had never responded. In the interim, sometime in October 1967, twenty-four-year-old Ann Soetoro and six-year-old Barry Obama boarded a Japan Airlines flight from Honolulu to Tokyo. During a three-day stopover, Ann took Barry to see the giant bronze Amida Buddha in Kamakura, thirty miles southwest of Tokyo. Then they boarded another plane, headed for Jakarta via Sydney.

In Honolulu, Barry had begun first grade at Noelani Elementary School, and upon arrival in Jakarta, Ann initially followed through on her promise to homeschool her son. Home was 16 Haji Ramli Street, a small, concrete house with a flat, red-tiled roof and unreliable electricity on an unpaved lane in the newly settled, far from well-to-do Menteng Dalam neighborhood. Jakarta was a sprawling metropolis, but one where bicycle cabs—becak, in Indonesian—and small motorbikes far outnumbered automobiles.

Outside of the privileged expatriate community, where young children attended the costly international school, “Jakarta was a very hard city to live in,” said another American woman—later a close friend of Ann’s—who lived there in 1967–68. One had to deal with nonflushing toilets, open sewers, a lack of potable water, unreliable medical care, unpaved streets, and spotty electricity. When Ann and Barry arrived, Lolo was indeed working for the Indonesian army’s mapping agency, though now, unlike four months earlier, he was based on the other side of Jakarta, not hundreds of miles away in far-eastern Java.