По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

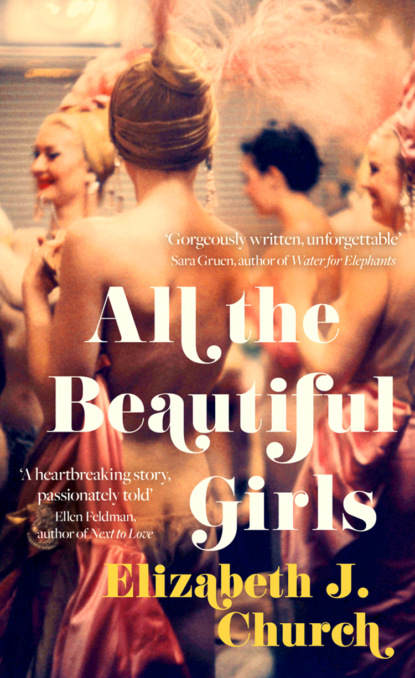

All the Beautiful Girls: An uplifting story of freedom, love and identity

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At dance class the next day, Mrs. Baumgarten delivered one of the Aviator’s books to Lily. It was a gilt-edged 1942 edition of Walt Whitman’s collected poems, and on a plain white strip of paper intended as a bookmark, the Aviator had written “The hungry gnaw that eats me night and day.” I understand this is your need to dance. She saw the line embedded in the poem “From Pent-Up Aching Rivers.” The gift, Lily thought, was not the book. It was his understanding.

IN THE WEE hours of the morning after she graduated as one of the top ten in the class of 1967, Lily left a bouquet of daisies on the dining room table. She set it next to a blouse she’d made for her aunt, along with a card that said Thank You on the front in silver embossed letters. Inside, Lily had written a paragraph of gratitude for taking her in, teaching her, and providing for her. She signed it with love because the other options—sincerely, fondly, best wishes—all seemed needlessly cruel. And maybe—in fact, honestly—she did love her aunt, despite everything. It was no one ’s fault that they were mismatched, just as much or more so than Mama and Aunt Tate had been. And Aunt Tate really had done her best. She simply wasn’t capable of more—or she might long ago have left her husband. Escaped Salina.

Lily didn’t leave anything for Uncle Miles, certainly no forwarding address or information other than that she was leaving Kansas to dance. Then, Lily walked out of the house and climbed into the Aviator’s waiting car.

It was barely after four A.M. when she stood with him in the bus depot parking lot. About her neck Lily wore a fine gold chain on which she’d strung her mother’s engagement and wedding rings—a graduation gift from Aunt Tate. Lily pulled the rings from beneath her blouse, fingered them and thought of her mother’s hands dusted in flour, sewing a button on her father’s shirt, and teaching Lily how to tie her shoes. Had her mother braced those beautiful hands on the dashboard when she saw the Aviator’s car coming?

“I’m sorry I didn’t make you a gift,” Lily told him. “But nothing would have been enough, and I didn’t know what would say goodbye in the right way.”

The Aviator took her chin in his hand. He lifted her face, and for a moment she thought he might kiss her lips. A part of her wanted that. Instead, he slipped his thumb into the cleft of her chin, let it rest there, calm and steadying. She saw that he might cry, and so she took his wrist, closed her eyes, and kissed his beating pulse.

Leaving the Aviator was like leaving her real family, once and for all. The finality of it hit her, hard, and she felt her knees threatening to drop her to the pavement. Instead, she turned and walked into the bus terminal.

AT SOME POINT, every girl in Kansas dressed as Dorothy for Halloween. Pinafore, petticoat, simple white blouse, a straw basket for trick-or-treat candy, demure ankle socks, and red shoes. Goodbye, Dorothy, Lily thought, good riddance to you and all of your “There’s no place like home” bullshit.

Lily remembered when a teacher had told them that Kansas was once a vast inland sea. She ’d hunted fossils with Beverly Ann and tried to imagine how change could have occurred on such a massive scale. She remembered the tadpoles she and Dawn had caught and watched grow. If Kansas could go from sea to prairie, if a frog egg could radically transform itself from an almost-fish with gills to an amphibian that left water for land, then Lily could transform, too.

At the Colorado border Lily decided that her new self deserved a fresh name. Lily Decker would become Ruby Wilde. She thought it worked—her dark red hair, the elegance lent by that extra e, like shoppe.

Lily looked at her palm, studying the lines of influence on her Mount of Venus at the base of her thumb. The lines were said to represent the friends, teachers, enemies, and lovers who change and shape existences. Lily had countless fine lines on her palm, and many of the lines touched, even traveled across her life line. She recognized the deep lines of her childhood: Aunt Tate, Uncle Miles. The Aviator. Her parents. Dawn.

People come and go, Lily thought. Sometimes they vanish unwillingly, the resulting break adamant, like a sharp slap of the ruler across the palm—decisive, unequivocal. Others leave with as little thought as the tip of the finger that snuffs out the life of an ant crawling across a pantry shelf.

Beyond her window, Lily saw fence posts and dull-eyed cattle. Black hawks circled, eyeing the ground for deer mice and lizards. Clouds coalesced and broke into discrete puffs. It was June 9, 1967, exactly ten years since her family had dissolved like sugar stirred into iced tea. Lily settled back into her seat and relaxed. She’d done it. Ruby Wilde was on her way.

(#ulink_244e97f6-4449-5a63-a581-43340ea51c6d)

1 (#ulink_6347fac4-e07b-5da0-92ff-56045081f69e)

She waited until the bus was safely within the boundaries of Nevada before opening the Aviator’s envelope.

June 9, 1967

Dear Lily,

There is more where this came from, but this is a start. It should help you to pay your rent and eat decently for a few months, until you find your place in the limelight. You haven’t seen much of the world, and I don’t know if you realize what an unforgiving place it can be. Be careful and pay attention.

If you need anything, call me.

Yours,

Stirling

Unforgiving? He must be kidding. She had already plummeted into the depths of that word, deeper than the Aviator could ever imagine.

He’d enclosed four fifty-dollar bills that looked as if they’d never seen daylight. She discreetly tucked them into her pink leather wallet, wary of the prying eyes of the passenger next to her. Ever since he’d boarded the bus in Utah, she’d felt him watching her. She refolded the Aviator’s letter and slipped it into her fringed leather shoulder bag.

Although they were excruciatingly close to her final destination, the bus pulled into a rest stop in Glendale, Nevada. After freshening up, she sat at the luncheonette counter, smoking and thinking that even though it was after ten P.M., she needed either a chocolate malt or a cup of coffee.

“Would you mind?” the watchful man from the bus asked, pointing to the stool next to hers.

“No.” She crushed her cigarette and decided her first Nevada meal would be ice cream. She laid down the menu as a signal to the waitress. The man had shaved, and now he smelled of Right Guard and Aqua Velva.

“May I treat?” he asked.

Ruby spun her stool and looked at him. He was probably about forty, forty-five, wore a wrinkled gray suit, a burgundy tie, and a gold tie bar. His face was soft, round, and he was balding, with outsized red ears. The man’s smile was friendly, and she decided to let him be gentlemanly. “Sure,” she said, “but I’m a cheap date—just a chocolate malt.”

“Make it two,” he said to the waitress, who slipped the carbon paper between tickets in her book and jotted down their order.

There was a moment of awkward silence until the man said, “Mason.” He held out his hand. “Mason Maddox.”

She remembered to use her new name. “Ruby”—she smiled—“Wilde.”

“Nice to meetchya, Ruby Wilde.” He fiddled with the long-handled spoon the waitress set before him and unwrapped his paper straw. “Going to Vegas to spend all your hard-earned money?” he asked.

“I’m a dancer,” Ruby said, feeling warm, easy, as she opened into her new self. She had a quick vision of a full-blown cabbage rose—pink, luscious, the scent of early summer before the heat set in.

“My daughter Rose works in Vegas. On my way to visit her.”

“She dances?” The waitress placed two thick malts on the counter. Ruby plucked the cherry from the top of hers and dropped it into her mouth.

“Works reception at the new Caesars. She’s been in Vegas almost two years now.”

“Does she like it? Las Vegas?”

“Loves it. But to be fair, she ’s comparing it to Salt Lake City, and there ’s one hell of a difference.” He laughed to himself, sipped his milkshake. “Mind my askin’ how old you are, Ruby?”

“Eighteen.”

“Tell them you’re twenty. It’ll be easier for work in the casinos. And”—he looked critically at her face—“wear more makeup. It’ll make you look older.”

“Okay …”

“Do you know anyone there? Got a place to stay?”

Ruby hesitated.

“I’m just concerned about you,” Mason Maddox said. “My daughter’s only a couple a years older than you, and the stories she tells … Well, let me just say, Miss Ruby, that I know my Rose isn’t telling me everything, but what she does tell me is plenty. You gotta watch out for yourself. Don’t trust anyone.” He stirred his shake. “Everyone’s on the make. Everyone.”

Ruby quietly focused on her malt.

“How about I do this.” Mason eased a napkin from the dispenser. He wrote out Rose Maddox, carefully printed his daughter’s address and phone number, and slid the napkin to Ruby. “Just in case,” he said. “I’ll let her know you might be callin’. She’s a good girl. She’ll help you out, show you the ropes.”

“Thank you.” Ruby folded the napkin and slipped it into her purse. “I mean it,” she said. “You’re kind.”

“Pleasure’s all mine,” Mason said, standing. “It’s what I’d want someone to do for my Rose.”

She finished her malt, had one more cigarette, and climbed back onto the bus. Thanks to the ice cream, Ruby managed to doze until the brakes sounded and the bus pulled into Las Vegas just after midnight.