По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

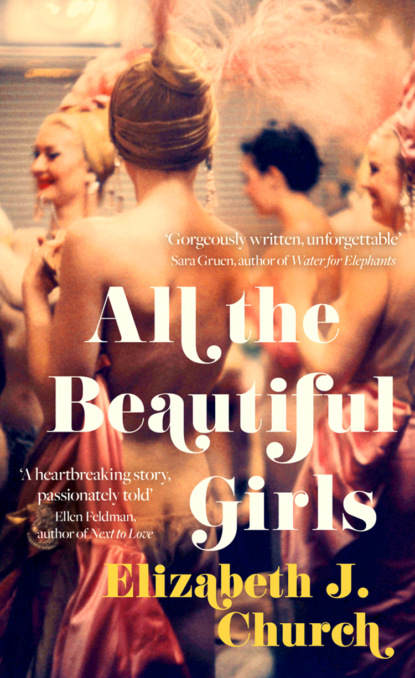

All the Beautiful Girls: An uplifting story of freedom, love and identity

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You’re growing up so fast. A young woman, nearly,” Aunt Tate said wistfully. “So much ahead of you,” she summed up.

“Does the aching go away?” Lily asked, and for a moment she saw confusion on her aunt’s face.

“Oh, the belly pain, you mean. Let’s get the hot water bottle.”

Aunt Tate helped Lily lie down with the soothing heat of the pig-pink water bottle planted squarely over her belly, and they split a special Almond Joy candy bar Aunt Tate called “medicinal under the circumstances.”

Lily fell asleep wondering about the connection between blood and womanhood. She hadn’t been able to make herself ask Aunt Tate why she was bleeding, if it had a purpose, other than inconvenience and ignominy. Was it something to do with God’s unending wrath toward Eve, the curse Aunt Tate talked about? Was that why only women harbored secret, open wounds?

ON SATURDAYS LILY swept and dusted. She got down on her hands and knees and scrubbed the kitchen’s green and white linoleum. In the bathroom, she held her breath and washed away the yellow splashes of urine Uncle Miles left on the porcelain toilet bowl.

Alongside Aunt Tate, she learned how to make stew and soups, chipped beef on toast, casseroles, and hash from leftover pot roast. She mastered pastry, crimping a perfect blanket of crust over apples, cherries, or peaches. Aunt Tate taught her to fold laundry properly, how to iron simple things like sheets, pillowcases, and dresser scarves. When Lily conquered the straightforward items, she moved on to more difficult things like Uncle Miles’ work shirts and Aunt Tate ’s cotton blouses.

One afternoon, Lily opened the linen cupboard and shifted a pile of sheets to make room for her fresh ironing. Beneath the sheets, she found a cardboard folder that held a portrait of her parents. Her mother wore a light gray suit with a big chrysanthemum corsage, and her father had his arm about her mother’s shoulders, an unmistakable flash of joy in his eyes that Lily thought she remembered, even if she could no longer hear his voice.

There was a newspaper clipping folded inside, and Lily read the article from the Salina Journal dated June 10, 1957, four years ago. It featured a picture of her family’s car, mangled and topless. Another picture showed the Aviator’s brand-new, black 1957 Chrysler 300-C, which the caption said was a production-line muscle car with enough power to reach one hundred miles per hour in second gear. At the time of the accident, the Aviator was traveling an estimated 130 miles per hour.

Lily saw decapitated and ten-year-old Dawn Marie Decker thrown from the car and the miracle of Lily Francine Decker’s survival. Sheriff Ingram was described as having hot tears in his eyes when he said that no one would ever know why the Buick had been traveling on the wrong side of the road. “Could be the Deckers swerved to avoid hitting a coyote,” he’d said. “Maybe a raccoon or a skunk. But it’ll be a mystery, always.” Ingram said the thirty-seven-year-old Aviator would not be cited, although he ’d been cautioned to watch his speed. “No one to blame,” the sheriff concluded.

Decapitated. Lily felt the word as a sharp, unexpected blow to her solar plexus. She hadn’t known. They’d kept it from her—the gruesome death of her parents. And the Aviator hadn’t told her the truth, not the whole truth. The Aviator had let her believe that the accident was his fault, but Lily’s father had been driving on the wrong side of the road.

Lily tucked the clipping and portrait back beneath the sheets and closed the cupboard door. She put it all back where it was supposed to be, buried and hidden away.

SHE LICKED HER fingers and touched herself the way Uncle Miles had taught her. She wet her fingers in her mouth once more and sent them back as quickly as possible, not wanting to lose the sensation she was building, a skyscraper of guilty pleasure and release. She needed to keep the pressure steady and so had the idea to wedge the satiny edge of her blanket between her legs. She squeezed with her thighs, tightened, released and tightened her muscles until it arrived—that sensation of heat and freedom.

After Lily was done, she swore she would never do it again. She would stop. No one had told her it was a sin or bad or sick, but she knew it was. If it had to do with Uncle Miles, it was bad. The knowledge of her perversity was solid.

Lily didn’t understand any of it—not the irresistible impulse to engage or any reason behind the pleasure. It was a disgusting need that Uncle Miles had ignited within her. Surely other girls didn’t feel this way, know these things, do these things. Her very core was diseased.

“I’ve been looking forward to this all day,” he said one summer night when Lily felt a soft, cooling breeze coming through her open window. The Sorensons’ yippy little dog had just finished a protracted, panicked bout of barking. Uncle Miles pushed up her nightgown and ran his rough hand up her leg. “You’re getting such long legs,” he said. “Young filly.” Uncle Miles’ hand reached her crotch. “What’s this?” he said. “Off. Get them off of you.”

“But—”

“Then I’ll do it.” He slipped his hand into the waistband of her panties and yanked. The sanitary belt stayed with the panties, slid down with them as he tugged. He spotted the pad.

“You’ve got your monthlies?” he said, pulling back.

She was surprised that Aunt Tate hadn’t told him, but she was instantly grateful that her aunt had kept it to herself.

“Since when?” Uncle Miles asked, and Lily realized that for some incomprehensible reason, Uncle Miles was suddenly worried.

“A few months.”

“Oh.” He reached for the bedcovers and threw them over her exposed body. “Shit.”

With the exception of a sporadic “damnation” when the wrench slipped and cut him or when the lawn mower refused to start, Uncle Miles rarely swore.

“Then that’s that,” he said, standing and looking down at her. He walked out of her room and actually closed the door completely, the click of the latch an unprecedented explosion of sound.

Lily lay there, trying to comprehend. Some part of her knew Uncle Miles was gone forever, that he wouldn’t come back. But why not? What had she done? And why was even a fraction of her feeling sadly rejected, as if she’d failed? Why was she anything other than joyfully relieved? Now what had she done wrong?

THROUGHOUT LILY’S EARLY teenage years, the Aviator continued to pay her dance school tuition. Lily studied tap and modern dance, which Aunt Tate pronounced “a good deal of meaningless thrashing.” Lily learned ballroom dancing and started to work on ballet positions (à la seconde, effacé), but Aunt Tate couldn’t afford the toe shoes, and because Lily would never presume to ask the Aviator for more, ballet remained a dream. Still, she could jitterbug and do the Charleston and shimmy and mimic Gene Kelly’s easy, athletic leaps and Cyd Charisse ’s sexy, long-limbed elegance. An American in Paris and Singin’ in the Rain instantly became her favorite movies when she watched them as reruns on Dialing for Dollars after school.

The Aviator faithfully attended all of Lily’s Tah-Dah! dance performances, and Lily knew he ’d be at the upcoming recital of Enchanted Woodlands, too. Some of the younger girls chose to be squirrels. One was a big, clumsy bear, and several flitted across the stage as chattering birds. This time Lily was nervous—largely (and as usual) because of the pressure she’d put on herself. With hard work, she’d earned a solo, which meant she could choreograph the final piece of the evening for herself.

Lily wanted to be different, to perform something that transcended childhood and matched the fact that she would soon be moving on to high school. In the library, she learned the word diaphanous and read the myth of Daphne, the beautiful nymph who spurned every suitor, even Apollo. When Daphne asked her father, a river god, to help her escape from Apollo, her father turned her into a laurel tree. It was an abominable, cruel solution. A daughter asked for help, and her father’s incomprehensible response was to sentence her to eternity as a tree, with roots bound to the earth.

Lily wanted to free Daphne—at least for a while—and so Lily’s Daphne leapt onto the empty stage and danced as if escape were possible. She wore a green leotard, chestnut brown tights, and she’d sewn lengths of pink, rose, and fuchsia ribbons to the arms of her leotard. A diadem of leaves interspersed with ribbons crowned her loose, flowing hair. She felt free, transported. And beautiful.

Lily covered every corner of the boards with her leaps, and she let her arms float in graceful, ever-moving arcs so that her ribbons wove patterns about her. She threw her head back, closed her eyes in rapture as if she were thrusting her defiant face into Apollo’s sun. Then, in keeping with the myth’s inevitably, Lily began to freeze. Mustering great dramatic authority, Lily stuck her feet to the floor of the stage. Inch by inch, with exquisite control and painful slowness, Lily stilled her body until only her fingertips quivered with musical breezes. The ribbons hung lifeless. She held her mouth to the audience in a silent, open O—an arrested scream.

There was a long silence, and then they applauded. Someone even shouted “Bravo!” Lily bowed, letting her ribbons trail on the floor of the stage, and as she calmed her breath, she felt the audience’s energy lift her skyward. She kept her eyes closed as a beatific glow possessed her. When one of the younger dance students touched her arm, Lily opened her eyes to a bouquet of lilies and baby’s breath. She cradled the flowers in her arms and made a final bow, hoping the Aviator knew her thanks—her debt—was to him.

In the hushed car on the way home, Aunt Tate said, “What do you call that?”

“What?”

“That kind of flailing.”

“Interpretive dance. It was my interpretation of the character, through dance.”

Aunt Tate sighed. “Well, I guess as long as we ’re not paying for it.”

A voice inside Lily said, Don’t let her take this from you. Still, it hurt. Wasn’t there anything she could do that would make her aunt proud?

Back at the house, Aunt Tate said that lilies smelled of funerals, and so Lily gladly set the vase on the nightstand next to her bed, where the scent of the Aviator’s tribute would perfume her sleep. Lying in the dark, still too fired up to sleep, Lily relived her performance, and she knew Aunt Tate and Uncle Miles had not succeeded. Lily had found a way; she ’d done it. The audience had not only seen her, they’d loved her. Lily Decker was not invisible.

A COUPLE DAYS after her dance recital, Aunt Tate left a gift on Lily’s bedside table, next to the vase of fading lilies. When Lily tore open the wrapping paper, she found a crystalline box with a butterfly suspended inside, its wings spread wide as if in optimistic flight. The creature’s wings were a stunning sapphire blue—vibrant, even in death. A card written in her aunt’s cursive read To match your beautiful eyes, and because you have more spirit than I ever did. And then, the most amazing, bewildering part of all—Aunt Tate had written, “Love, Aunt Tate.” LOVE.

6 (#ua23ae627-e042-52ae-96f5-4f4bea66c68a)

In high school, the bones of Lily’s face emerged like the visage of a goddess rising from a deep seabed. She was no longer merely pretty or interesting; her beauty arrested. When she walked the sidewalks of downtown Salina, men spun in their tracks to look at her. Women eyed her with a mixture of studied curiosity and envy. Once, when she was grocery shopping with Aunt Tate, a complete stranger stopped to say, “Now I understand what was meant by ‘the face that launched a thousand ships.’ ” To which Aunt Tate replied, “Well, we ’re in Kansas, and I don’t see any ocean, do you?” At that, the woman walked on, but she turned briefly to shake her head and give Lily a secret, understanding smile.

Any baby fat that had dared to linger now melted from Lily’s body. Standing five foot ten, she had a dancer’s slim hips, abundant breasts, and she wore her hair bobbed and blunt cut with glowering bangs. Although it was already passé, Lily cultivated beatnik black, morose cool, and mystery touched by a hint of simmering, bedrock rage. She lined her eyes heavily in black, and the look suited her in a way that the perky flips, teased mountaintops of hair, and bright polyester fashions of the midsixties did not.

The Aviator remained in her life, a steady presence, a secret ally. For her sixteenth birthday in 1965 he gave Lily a light blue suitcase record player and fifteen dollars she could use to buy whatever albums she wanted. It was Dylan who spoke most clearly. She took to heart his advice that if you weren’t busy being born, then you must be busy dying. She was a disciple of his cynicism, his challenges to everything from teachers to the president to God. Dylan was her fellow iconoclast; like Lily he distrusted absolutely everyone. With the volume turned down low to keep Uncle Miles from shouting at her, Lily dreamed of highways, of the infinite variety of mountains, of escape.

At age sixteen, Lily walked into Masterson’s Grocers and applied for a job. She needed spending money for makeup and sewing supplies, and Uncle Miles had decreed that it was time she contributed to her upkeep, which he set at thirty-five dollars per month. The manager, an already obese twenty-year-old named Harold, had dense patches of acne on his cheeks and daubs of ketchup on his mint-green clip-on bowtie. He hitched up his pants and slowly eyed the curves of Lily’s body, letting her know in no uncertain terms why he’d be hiring an inexperienced girl. Harold handed her two pink-and-white uniforms to try on for size, and as she undressed next to shelves of canned goods in a back stockroom, she wondered if he was standing at a peephole, watching. Lily imagined his gaping mouth, his widened eyes, and she took her time before choosing the shorter, tighter dress, the one that would best follow the contours of her body.

Harold assigned her to mark prices and stock shelves—an obvious ploy to have her bend over repeatedly, lean over cases with her box cutter and reveal her cleavage. She was on display, just like the towers of canned peaches and pyramids of apples and oranges on the This Week Only! promotions at the endcaps of the grocery aisles. But Lily didn’t mind. The grocery store was merely another stage, another setting in which she could experiment, learn what effect her lush body had on men.

She watched Harold’s face, the faces of men who came in weary from driving a combine all day, their necks and arms dusted in wheat chaff. Lily learned how to signal bashful innocence, along with a sort of vulnerable availability. She learned how to encourage men to help her when she couldn’t quite—not quite but almost—reach the shelves where the Corn Flakes, Froot Loops, and Alpha-Bits cereal boxes lived. She came to realize that men didn’t want to see competent independence; they wanted to see a slice of need. So she gave them that. Lily knew, too, that none of them considered that she might be intelligent. Her agile mind was not something a single, solitary man cared to consider.

EVERYONE WAS READING Truman Capote’s new book about the murders in Holcomb, just a couple hundred miles southwest of Salina. Even Uncle Miles had thumbed through the novel, afterwards puffing out his chest and announcing that those two killers would never have gotten through the door of his home. Lily imagined her uncle ineffectively bonking one of the killers over the head with his dusty Hawaiian ukulele, like the cartoon horse Quick Draw McGraw’s alter ego, the masked and black-caped El Kabong. Kabong!

Lily also thought a lot about the killer Perry Smith, about his childhood, his longing for love and his constant leg pain. It threw her—that Perry could be the sympathetic one in the duo, the one with artistic aspirations, but the one, ultimately, who did the butchering. Lily also wondered about the murdered teenage girl who had hidden her watch in the toe of her shoe. The unfairness of it all. Even if you followed all the rules—got straight A’s as Lily did—it was no guarantee against wanton destruction.

The state of Kansas had hanged the two men last year, in 1965. For so long, it seemed to be the only thing on the news. Perry Smith and Dick Hickock murdered Kansas’ innocence. They killed the myth of idyllic, small-town safety far from the big cities with their slums, poverty, and drugs. Now, people in Salina locked their doors at night. And yet, Lily didn’t share the titillating fears of the girls at school; she knew that danger didn’t necessarily come from a stranger.