По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

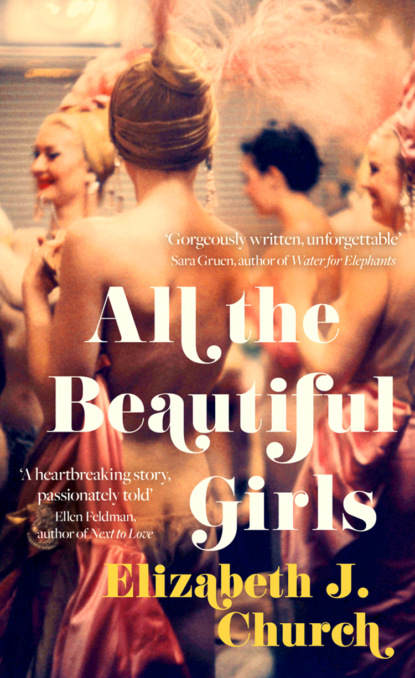

All the Beautiful Girls: An uplifting story of freedom, love and identity

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I’m here today as the special guest of Lily Decker,” he said. “Lily, please stand and let your schoolmates thank you for making this happen.”

Basking in the glory, Lily stood, thinking her mouth could not stretch widely enough. All the kids who’d pointedly skirted around the girl of contagious calamity now cheered loudly.

The Aviator spoke about flying bombers over Europe during the war, of the new aircraft he was testing high above the plains of Kansas and the entire Midwest, and he cited facts and figures about the speed of the planes, what he saw when he catapulted beyond the clouds. The boys shouted questions about how many enemy cities he’d destroyed, and the girls—who were for the most part absurdly shy—asked questions about whether people on the ground really looked like ants, if the Aviator could see into windows and know what families were having for dinner.

When it was all over, the Aviator asked Lily to come up and stand beside him. She made sure her bobby socks weren’t drooping and smoothed her green-and-blue plaid dress as she walked to the front of the gymnasium. The Aviator held a small corsage with two white roses and some airy greenery.

“This is for my good friend Lily,” he announced as he pinned the corsage to the collar of her dress. Lily’s heart soared—high, into the stratosphere, venturing far beyond any altitude even the Aviator had ever sought.

AUNT TATE SAID Lily could go look at the elephants, but she had to be back in ten minutes. Lily hopped down the bleachers, holding her paper bag of popcorn against her chest so that she wouldn’t spill any. She could hardly wait for the show to begin, because there would be trapeze artists in sparkly costumes and maybe those girls in leotards who twirled on ropes.

Lily made her way past the man selling chameleons tethered on lengths of red thread, and then she stood in the straw in front of the elephants. She decided she liked the one named Bruno best. Lily wanted to run her hand across the terrain of his gray skin, to smooth away his wrinkles and try to make his eyes look less sad. Other kids were holding out fistfuls of peanuts, but Bruno ignored them all. He turned his head and stared morosely at the red-and-white wall of the canvas tent.

“How are you, Miss Lily?”

It was the Aviator, standing at Lily’s elbow. He wore a ball cap and a forest-green T-shirt, and Lily saw half circles of sweat beneath his arms. July’s heat was upon them. Soon enough, there would be days in a row of 100-degree temperatures that left everyone in Salina wet and wilting.

Lily grinned. “Hi,” she managed and then offered the Aviator some of her popcorn. He accepted a few kernels.

“Are you shy today?” he asked. Lily nodded, and he continued. “Well then, how about I ask you questions? All right? Let’s see,” he said, putting his finger to the center of his chin and pretending to be deep in thought. Lily giggled. “Tell me what you like to do. What’s your ten-and-a-half-year-old heart’s favorite pastime?”

Lily was thrilled that he knew enough to add that half year to her age, but she wasn’t used to being asked what she liked. She was used to doing what she was told or suffering the hairbrush—Uncle Miles’ favorite form of punishment, one he reserved for offenses like sassing back or stealing nutty chocolates from the box next to his ugly brown turd of a recliner.

“I like to dance,” Lily said, and then feeling braver, she handed him her bag of popcorn, wiped her hands on her purple shorts, and stepped back from the elephant enclosure. Lily showed the Aviator some of the steps she’d copied from Dinah Shore’s show. She pointed her toes, held her breath, and performed a passable pirouette.

“What’s your favorite kind of dance?” he asked.

“All kinds. Any kind,” she said. “I love the June Taylor Dancers. I’ve seen them on The Ed Sullivan Show.”

“They’re pretty good,” he said, munching on a few more pieces of her popcorn.

“They kick like this.” She turned sideways, kicked as high as she could, kept her balance. “And when they make those patterns, like a kaleidoscope—I love that. They’re magic. Oh,” she added, “and the outfits. Sequins and feathers. Headdresses!” Lily could hear how fast the words were coming out of her mouth.

“So, dancing makes you happy.”

“More than that,” Lily said, looking up at him. “When I dance—when I dance, nothing else matters. Everything else disappears. There is only dancing.” That was it. Dancing took her to another world, a world that Uncle Miles could not reach. A world where her lost family was a faint shadow, not an omnipresent, weeping wound. When Lily danced, she was not a misfit. She belonged.

But she couldn’t bring herself to say all of this to the Aviator. Instead, she simply said, “I feel happy when I dance. Free.”

“All right then,” he said, just as the band began playing an upbeat song. Lily was torn—she had to get back to her aunt, but she wished she could ask him to come sit beside her.

“Here.” He handed her the popcorn. “You can’t miss the show.” He held out his hand, and she took it. “I was very glad to see you, Lily Decker. Now, you go have fun, and later you can tell me what you think of pink and green and blue and yellow trained poodles, all right?”

Lily laughed. There couldn’t possibly be such a thing. The Aviator was funny.

“I’m not kidding,” he said, touching the brim of his ball cap in a mock salute. “They dance, too, but not as well as you! Now, promise me you’ll have a good rest of the summer, all right?”

“I will!” Lily skipped a few steps toward the bleachers and then turned to wave to him one more time. She watched him cross the parking lot, stand beside his tuxedo-black Corvette, and light a cigarette.

A week later, Lily received a card in the mail that said she ’d been given a Tah-Dah! Dance Studio scholarship, along with a stipend to pay for a leotard, tights, and appropriate dance shoes. It was signed “Your Secret Benefactor.” Aunt Tate said, “Someone has money to burn” but otherwise manifested no curiosity. And so after school Lily rode her faded red bicycle to the studio. It gave her two days a week when she was out of the house, free from chores and the lead-weight sensation of knowing Uncle Miles was due to come through the kitchen door, smelling of oil and diesel and sweat.

UNCLE MILES SAID, “Tonight we experiment.”

September’s full moon through the window made everything silvery bright, lit the edges of things, made silhouettes of her desk lamp and her bureau with her ballerina jewelry box. Lily jammed the ends of her fingers into her mouth, bit down to keep quiet. She squeezed her eyes shut, tight. Warm tears eased their way from the corners of her eyes, ran into her hair, and wet her pillowcase.

Uncle Miles put his mouth to the center of her. He was moaning, which made a buzzing bee vibration that journeyed from his throat, his lips, to her core. And then she felt the growing heat of her own flesh in response. She fought against it but couldn’t help it. “Oh!” she cried, a surprised baby-bird voice. “Oh, oh, oh!” He held her pelvis as if it were a bowl.

She thought that she might explode, that she was descending, plummeting, and it was release and good and hot and out of her control and sick and bad a disease and the worst thing ever that Uncle Miles had done but it felt good. It felt good. It felt good. Oh, no—it felt good. How could her body betray her?

“You like it.” His whisper left a hot brand of accusation against the side of her neck.

Once he was gone, she told herself that tonight was the exception to the rule. Tonight, it was okay to cry. With her face pressed into the wet pillow to muffle the sound of her confusion, Lily cried her shame. Her need. She cried a poisonous blend of gratification and disgust, of wonderment that Uncle Miles had given her pleasure, which was more frightening than any of the painful, awful things he’d done in the past. She cried her rupture, her irreparable breakage.

5 (#ua23ae627-e042-52ae-96f5-4f4bea66c68a)

The light from the gooseneck lamp on top of the church organ turned Mrs. Olson’s face cadaver white as she played “O God of Mercy, God of Might.” Seated next to Aunt Tate in the unforgiving wooden pew, twelve-year-old Lily wrapped her arms around her gut, which had harbored a deep, persistent ache since before the second hymn. Finally, Pastor Lester intoned the benediction and released the sanctified congregation.

Lily immediately headed downstairs to the church bathroom, which wasn’t much more than a stingy coat closet. When she looked at the crotch of her panties, she saw blood. Oh no oh no oh no oh no. A string of dark, thick blood dripped from inside her, and there was more blood in the toilet bowl.

Was this God’s doing? Was this one of the things that the all-powerful, vengeful God did to punish bad girls? She knew that what she did with Uncle Miles was evil, and God did seem so very fond of bloody atonement. Lily wadded toilet paper into her panties and then sat uncomfortably through her sixth-grade Sunday school lesson.

Aunt Tate was waiting in the car when Lily finished class. “What did you learn today?” she asked, waving to some of her Bible-study friends like Margaret Steepleton, who kept a handkerchief tucked between her bulwark breasts and blew her nose loudly at least seventeen thousand times during the pastor’s tedious sermon.

“The story of the prodigal son,” Lily dutifully reported. Then she took a deep breath, steeling herself to tell Aunt Tate about the blood and possible impending doom. “Aunt Tate? I’m bleeding.”

Aunt Tate turned to look at Lily. “Where? Did you fall?”

“No.” It was hard, but Lily knew she needed help, that something was horribly wrong. “Down there,” Lily whispered, looking out the windshield and across the street to the Texaco station, thinking about the smell of gasoline, the way oil puddles on the asphalt formed galaxies of rainbows. “It hurts,” she said, still avoiding her aunt’s stare and holding a hand to the ache in her belly.

“Between your legs.”

“Yes.”

Aunt Tate closed her eyes and leaned forward until her forehead rested on the steering wheel.

So, it was true. Lily was going to die. Or at least she was very sick, and there would be hospital bills. She’d bankrupt them. They would be roaming the streets, penniless.

Margaret Steepleton knocked on Aunt Tate’s window. “Tate, honey? You all right?”

Aunt Tate rolled down her window. “She ’s got the curse,” she said, tipping her head in Lily’s direction. “First time.”

Mrs. Steepleton leaned in the window and beamed across the seat at Lily, “Congratulations, sweetheart! Now you’re a woman!”

The curse? Since the accident, Lily had always known she was cursed. But was it a curse simply to be a woman?

“Lord, help me.” Aunt Tate sighed as Margaret Steepleton trundled off to join her husband and two boys. Her aunt’s voice was flat and unyielding, like the iron skillet that wouldn’t fit in the cupboard and so sat on the stove’s back burner, black, heavy, and inert.

They stopped at the drugstore on the way home, and Aunt Tate bought Lily a sanitary belt and a big box of napkins with a picture of a dreamy woman strolling through meadows of flowers. She showed Lily how to wear the belt low on her hips and had Lily practice attaching the napkin tabs snugly to the belt’s metal fittings.