По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

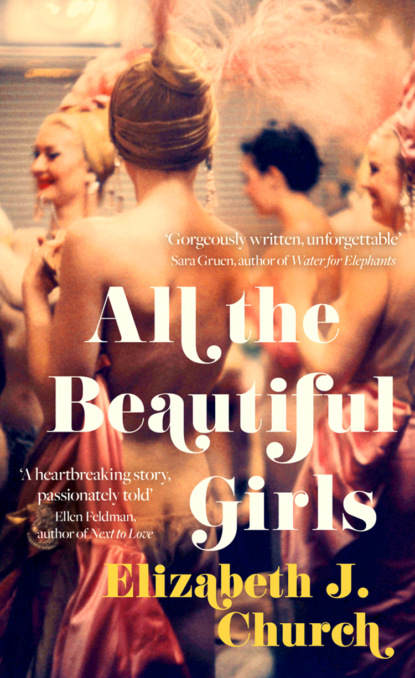

All the Beautiful Girls: An uplifting story of freedom, love and identity

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Other than perfunctory, necessary phrases, it was the first time Aunt Tate had spoken to her since the night of the fundraiser. Lily recognized the overture, released the pressure on the sewing machine’s knee-operated control lever, and peered up at her aunt, who looked completely enervated, as if she hadn’t slept in weeks. Aunt Tate was pathetic, Lily realized—a weak, albino stalk of a flower struggling to grow in the dark of a closet shelf.

I’ll escape, Lily thought, but this poor woman will never leave. I’m stronger than the both of them. And so, feeling somewhat conciliatory, Lily said, “This is my final project for Miss Lambkin’s class.” She held up the deep rose brocade. “It’ll be a lined evening-dress jacket, something I can wear over a skirt, maybe dress up with a piece of costume jewelry.” She ’d already sewn a pair of bell-bottom pants out of the material and loved the way the fabric stretched across what some of the other dance students referred to as “the Grand Canyon of your hips.” That canyon took two hundred sit-ups a night on the rag rug next to Lily’s bed, but it was worth it.

“Pretty,” Aunt Tate said. “But it’s musty in here. You should open a window.” She touched Lily’s shoulder fleetingly, so lightly that it could instead have been the minute brush of a passing moth’s wings.

“Aunt Tate?”

Her aunt paused but kept her back to Lily as if she somehow knew that Lily was going to take that one, placatory gesture and use it to open a chasm in their lives.

“I’m not a liar. I never have been,” Lily said and watched her aunt’s back stiffen.

Without a word, Aunt Tate left the room, and soon Lily could hear her in the kitchen, putting together the evening meat loaf.

Lily sat with her hands in her lap. She picked a few spent threads from her jeans. It was only when she heard her aunt sniffle and then blow her nose that she knew Aunt Tate was remembering all the nights Uncle Miles had left their bed and made his way down the darkened hallway to Lily.

7 (#ulink_9891bf55-83b7-5b9f-88cc-ea7b3b05ccec)

“But I do have a plan,” Lily said as the Aviator stood beside her. Although it was her day off, she was in the produce section of Masterson’s, doing Aunt Tate’s grocery shopping. A couple of women who’d been poking at the pears and cantaloupes looked up, but the Aviator charmed them with a smile, and they returned to their quest for peak ripeness. “I do have a plan,” Lily repeated.

“College?” He filled a paper produce bag with exactly seven Granny Smith apples and folded down the top with precision.

Lily snorted. “No.”

“Why not?”

“For starters, we can’t afford it.”

“But you can.”

“Right,” she said, looking at her aunt’s list, the one her uncle had added to in his left-handed, back-slanting cursive: dow nuts, choclut Marshmello cookys.

The radio station was playing the just released Beatles album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and Lily heard the lyrics of “She’s Leaving Home.” It was as if the Beatles had written the song just for her. The girl in the song stepped outside her front door and was free. Soon, Lily would do the same.

Seeing her distraction, the Aviator said, “Let’s talk in the parking lot.”

Lily sat in the passenger seat of the Aviator’s Thunderbird and double-checked the change the clerk had given her. She folded the receipt and shoved it all into the front pocket of her hip-hugger jeans.

“You’re a bright, bright girl,” the Aviator began, and she could smell his aftershave—a tart, citrus scent. He was wearing camel-colored khakis and a soft, white cotton shirt with the sleeves rolled loosely to his elbows. His fingernails were perfectly manicured, the nails buffed—a decided contrast to the decades of grease that accumulated beneath the nails of Uncle Miles’ sliced and diced mechanic’s hands.

“I’m a dancer. Not a college girl.”

“With an IQ of 155.”

“Who says?”

“Your guidance counselor.” He pushed in the cigarette lighter when he saw her shake a Salem from her pack.

“You were talking to Mrs. Holcomb about me?”

“I was.” He held the hot, orange coil of the lighter to the tip of her cigarette.

“I didn’t even know,” she said, rolling down the window and blowing smoke out into the parking lot. “I purposely did not go in to hear my scores.” Lily noticed that the Aviator smoked Marlboros. “Come to Marlboro Country,” she said, using her deepest voice to imitate the commercial. It fit the Aviator—the long, lean, isolated cowboy who was a man in every sense of the word. Took no guff, lived life his way.

He sighed. “I’m trying to have a meaningful conversation with you.”

“I know,” she said, pulling open the ashtray, tapping her cigarette. It didn’t surprise her that the Aviator’s ashtray looked as if it’d been washed clean in a sink. “You’re a bit of a neat freak, aren’t you?” she said.

“I like to do things right. Which is why I’m trying to talk to you.” Together they watched a young mother pushing a baby stroller while trying to pull up the strap of her shoulder bag. “You realize that 100 is average. A score of 155 is in what’s considered the very superior range.”

She hadn’t. All she knew was that when they took the test, she’d finished an easy twenty minutes before everyone else, and not because she’d put her pencil down and decided not to try.

“Let’s go at it from another angle,” the Aviator said, all efficiency and logic. “What is your plan?”

“To dance.”

“To dance.” He sighed. “A girl with an IQ of 155 should be capable of more specific planning. Even if she has been brought up by heathens.”

“You know, that’s what my dad called them. Heathens,” she said, looking at the Aviator, his upright posture, his flat abdomen. She saw something flash across his face—a mixture of pain and memory. “I’m sorry,” Lily said, touching his forearm. “I didn’t mean …”

“Do you see the irony of this?” he pleaded. “You? Apologizing to me?”

A soft rain had begun to fall, dotting the windshield with drops that ran until they randomly joined each other. Is that what people did, too? Lily wondered. Fall and drift until they collided with one another, the way the Aviator had collided with her ten years ago?

As he rested his fingertips between his brows, she realized her hand was still on his forearm, and she kept it there, increased the pressure. “You’ve been good to me,” she said. “Better to me than anyone else. I’ve always known I could depend on you.”

“Then let me help you. Let me help you with college. There’s money,” he said, now earnestly looking at her. “I’ve saved. You have a college fund. Please don’t throw your life away.”

She took back her hand, stared into her lap. “Thank you,” she said. “I’m grateful, really. But if you truly want to help me, then help me get to Las Vegas. To dance. That’s what I want.”

“Vegas?”

“Mrs. Baumgarten says it’s the best place for jazz dance. A place where I can learn from real pros. Accessible,” she said, coming up with the best word she could think of to summarize the perfection of her Baumgarten-assisted plan.

She watched him struggle with the idea, weighing his will against hers. Finally, he said, “That’s what you really want? You’re certain?”

“It’s the one thing I do know,” she said, simply.

“Well then. I won’t stand in the way of your dream.”

You can’t stand in my way, she thought but did not say. No one can.

She thought about explaining to him that dance was something she needed. How it purified her body. How, when she exerted herself physically, she felt the strength of her limbs, that they belonged only to her. That for however long she moved to music, Uncle Miles’ proprietary insistence became obsolete. But Lily didn’t explain. She could not pass through that stone wall from shameful shadow to bright sunlight—not even for the Aviator.

The rain came down more insistently, and through her open window it wet the sleeve of her paisley-patterned blouse. “I have to get going.” She used her sleeve to wipe water from the car upholstery. “Or I’ll catch hell.”

“That’s exactly what I’m afraid of,” he said, his voice soft, sad.

Taking the grocery bag into her arms and opening the car door, Lily pretended not to understand.