По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

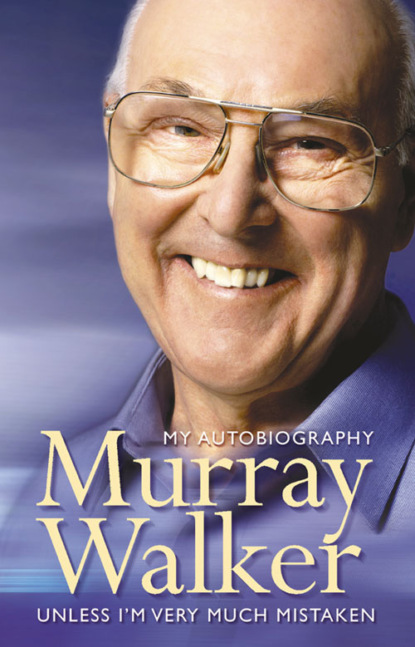

Murray Walker: Unless I’m Very Much Mistaken

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But then came the call via a telegram. ‘We’re ready for you now, Murray. Report to the 30th Primary Training Wing at Bovington, Dorset on 1 October 1942’. I went there as a boy and rather more than four years later was demobbed at Hull as a man.

CHAPTER TWO Tanks It Is Then (#ulink_5ef169ce-f9ed-5935-ba15-add6026f2a3a)

In August 1939, at the age of 15, I was having the holiday of a lifetime in Austria, accompanying my parents to what was then the most prestigious event in the world of motor-cycle sport – the International Six Days Trial. Sadly, like the Mille Miglia and the Targa Florio, it has long since been discontinued because of road congestion, but then it was exactly what its name implies: a gruelling, and virtually non-stop, road time trial for modified road bikes with tremendously demanding speed stages. Britain excelled in the event and in 1939, following three successive British victories, it was to be held in Austria. Following its annexation by Germany, Austria was totally under the control of the Nazis, who offered to give Britain an organizational rest and to base the event at glorious Salzburg.

It was a superb location amid the glorious Alpine scenery and my father, who knew the event thoroughly as ex-captain of a winning International Trophy team, had been invited by the War Office to give expert guidance to the British Army teams. The political situation was extremely tense with the threat of war between Britain and Germany, and while we were in Salzburg the Foreign Ambassadors of Russia and Germany, Molotov and Count von Ribbentrop, signed the Russo-German non-aggression pact. Hitler was aggressively rattling his sabre at Poland and the inevitability of war was gloomily forecast. In those days international communications were not as they are now, so the War Office said that in the event of, and only in the event of, an extreme emergency they would send a telegram detailing action and instructions.

Unusually for anything German, the Trial suspiciously showed every sign of having been hurriedly thrown together, almost as though they hadn’t really expected to be holding it. ‘There will be no problem,’ said Korpsführer Huhnlein, the Nazi boss of all German motor sport, ‘as there will not be a war now that we have signed the pact with Russia.’ On day five though, with all the British teams in very strong positions, a telegram that had been delayed for 24 hours arrived from the War Office, reading: ‘War imminent. Return immediately.’

Panic stations! While maps were urgently consulted to find the quickest route to the border, my father went to see Huhnlein.

‘We’re off,’ he said.

‘Why on earth are you doing that?’

‘Because the British War Office has instructed us to go.’

‘But there isn’t going to be a war and even if there is I give you my personal guarantee that you will all be provided with safe conduct out of Germany.’

‘Just one question,’ said my father, ‘What is your level of seniority in the Government?’

‘I am ranked number 23,’ said Huhnlein.

‘Well what happens if any of numbers one to 22 reverse your promise?’

‘That wouldn’t happen.’

‘Sorry, but we cannot take the risk. We go.’

For me the trip had been wonderful: the long car ride from England to Salzburg in my father’s Rover, exploring beautiful, Mozart-dominated Salzburg with my mother, watching the riders race by, the charm of the sun-soaked Alpine scenery, and the quaint Austrian hotels. The dash home through France was full of drama too but shortly after we returned to Enfield Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany for the second time in 30 years. Not so very much later I would be heavily involved in it myself. But first, back to school and glorious Devon, my scholarship at Dunlop, and, as my time approached, the decision about how I could best get into the war.

If you haven’t actually been in one, no matter how much you’ve read about it, you just don’t realize how horrific war is, how brutal, bestial and mindless. My image of tank driving included racing across the desert trailing great plumes of sand, having leave in exotic Cairo and being in my element with something mechanical. It was an ignorant and absolutely pathetic attitude but I was fresh off the farm, full of patriotic fervour, desperately wanting to do something about the evil which then looked likely to overcome the world. So once I got the call on 1 October 1942 I took the train from Waterloo to Wool in Dorset and reported for duty as number 14406224 at the 30th Primary Training Wing (PTW) at Bovington.

Bovington was and is the home of the Royal Armoured Corps and the whole area seethed with tank activity. There were gunnery ranges at Lulworth, the workshops, the wireless schools, the maintenance areas and driving ranges, not to mention the NAAFI – Navy, Army, Air Force Institute – Bovington’s centre of social activity and culinary excellence. (‘A char and a wad please, dear.’) It was a popular belief that they put bromide into the buckets of tea to suppress the libido of the licentious soldiery. If they did it was just as well, for the fraternization between the ATS girls and the lads was frequent and vigorous enough as it was.

My ignorance of life outside my loving family and school friends was compounded by my youth and inexperience so the 30th PTW was an exciting new experience and a huge culture shock for me. As a wet-behind-the-ears army private, I found myself amongst all sorts of people that I’d never come across before. In the bed on one side of me in the barracks room was an incredibly upmarket chap, whose name I have genuinely forgotten and whose general uselessness was well nigh unbelievable. On the other side was a laconically lovely bloke called Ted Nicklin who, if I remember correctly, was a welder from Walsall and as streetwise as they come. I am convinced that living as part of such a disparate mix did me all the good in the world, because it taught me there were other points of view, other ways to speak and more ways than one to skin a cat.

The 30th PTW was all about the beginnings of discipline – what armies win or lose by. ‘Do what you’re told. Don’t question it. Do it!’ was the unbreakable rule at the 30th and rightly so. Soldiers in combat must instinctively obey, not argue whether their orders are right. So seemingly endless drill parades, standing rigidly to attention when addressed by anything senior to the regimental goat, kit cleaning, sentry duty, assault courses and physical training were the order of the day, every day. If you were lucky enough to have leave, you had to report to the Orderly Sergeant for inspection before you were allowed to depart the barracks. He would closely inspect the backs of the tiny brass buttons in the rear vent of your greatcoat and the bit between the heel and the sole of each of your boots to make sure they were highly polished. Daft? No, it was discipline. But by far the worst thing as far as I was concerned was sentry duty.

It was winter and very cold and the system was two hours on and four hours off – dressed in full order. Battledress trousers and tunic, webbing belt and gaiters, boots, greatcoat, a gas mask satchel strapped to the chest, rifle and ammunition pouches and, literally, to top it all, a steel helmet. Clumsily clumping off to the sentry position in that lot was bad enough, but then standing in one spot for two hours of freezing night-time monotony was purgatory. But worse was yet to come. When you thankfully returned to the barracks room for an enamel mug of tea and four hours off, you had to sleep on the floor, or try to, without removing any of your kit – including your steel helmet – only to be woken for the Orderly Officer’s inspection just as you’d dropped off.

Eventually, as a result of all this marching, cleaning, running, jumping, parading, sentry-going, weapons inspecting, church parading and general hammering into shape I was ready to move onwards and upwards to Stanley Barracks. Not now as a humble Army Private but as a very proud Trooper to the 58th Training Regiment of the Royal Armoured Corps. Still at Bovington – but the first hurdle had been cleared.

Psychologically the 58th Training Regiment was on another planet because now I felt as though I was really on my way to the commissioned rank to which I had always aspired. My army ambition was geared to it and I would have been gutted and ashamed if I hadn’t made it. Life was at a higher level and altogether more specialized, in that it was more mechanically and ‘tank’ oriented with six months of driving, gunnery, wireless and crew commanding instruction.

Learning to drive was great. I was already proficient on a motor cycle, thanks to the 1928 250cc Ariel Colt my father had given me, but driving on four wheels was something new. We had to learn in a Ford 15cwt truck, which had a V8 engine and whose clutch was either in or out; nothing in between and a bit like a Vincent-HRD 1000cc motor cycle. Get it right and you went: get it wrong and you stalled. By the way, I’ve never taken a driving test in my life, because when I came out of the Army in 1947 you didn’t have to – all you needed was a certificate of proficiency from your Regimental Technical Adjutant. As I was the Technical Adjutant I didn’t find that too difficult!

So in the 58th it was not just more assault courses, physical training, marching, drill, belt and gaiter blancoing and ghastly sentry-going, although there was still plenty of all of those, but also getting to grips with the rudiments of being a ‘tank man’ – gunnery and maintenance, tactics and wireless, weapons handling, and enemy tank recognition. I’ll never forget the first time I drove a tank. It was a 20-ton Crusader and I can still feel the thrill as I hunkered down into the driver’s compartment, with its 340bhp 12-cylinder Liberty engine thundering away behind me. Rev it like mad, clutch up and – GO! With the crash gearbox in top it could do 40mph in the right conditions and, believe me, that felt more like 400mph. In the Crusader you steered by pulling two metal bars like pencils that braked the appropriate track and made the tank turn one way or the other. You felt invincible as the whole thing noisily bucked and plunged, ripped and roared its way ahead. Magic! I’ve always been grateful for the fact that I was one of the lucky ones: my tank was never hit by an armour-piercing shell from the Wehrmacht’s awesome 88mm anti-tank gun, my turret never penetrated by the blast from a terrifying Panzerfaust and I was never hit by mortar fire.

I loved it all at the 58th except two things: Morse code and Corporal Coleman. Morse code was my bête noire. I could never get my head round having to tap out electrical sound messages, machine-gun-like, in the form of dots and dashes with a key that moved only a fraction of an inch. But I beavered away at it and became just about good enough to get by. Corporal Coleman was something else though. At the 58th you may have been potential officer material but you certainly weren’t yet an officer cadet – or likely to be unless you played your cards right. Officers were gods and Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) were all-powerful. A bad report from an NCO could ruin your chances and they all knew it.

Well into my time with the 58th I got a simple cold which I ignored. With all the assault courses, getting sweaty, swimming icy rivers in battle order and other physically demanding things, it rapidly got worse. Like everyone, the last thing I wanted to do was to report sick, because if you had to go to hospital you were automatically retarded. So I didn’t … until ultimately I could hardly stand up and simply had to. Sick parade meant you had to assemble your kit for inspection by the Orderly Corporal – in a specific way to a very specific pattern. Highly polished boots with their soles upward. Highly polished mess tins alongside them. All your clothing folded and arranged a specific way, millimetrically precise and faultlessly creased. Blankets folded and gas mask, webbing equipment and cutlery all present and correct and spotlessly clean. Then you stood, alone and ramrod-erect, to attention at the end of your bed whilst the Orderly Corporal gave it his minutest attention.

Enter Corporal Coleman. Not, in my admittedly biased opinion, one of nature’s charmers at the best of times. Unsurprisingly my kit hadn’t been laid out as army-approved as it might have been and it didn’t go down well with Corporal C, who swept the whole lot on to the floor, kicked it round the barracks room and shouted, ‘Now do it all again – and properly!’ Or rather less refined words to the same effect.

Remember what I was saying about army discipline? There was no point in protesting and anyway I was in no state to, so I did as he said. And, having made his point, it was to his satisfaction this time. Then I dragged myself off to see the MO, who said, ‘You’ve got pneumonia. You’re going to hospital.’

I’m not a chap who holds grudges but for many years I dreamt of meeting Corporal Coleman again in circumstances where I held the upper hand. But I never did and in spite of my long hospitalization I returned to the 58th, completed my training successfully enough to be selected for my War Office Selection Board (WOSB) and appeared before it. I made the grade and, to my unbounded pride and joy, was told to report as an Officer Cadet to number 512 Troop Pre-OCTU (Officer Cadet Training Unit), Blackdown. Yes! Yes! Yes!

It was at Blackdown that Sergeant Major Hayter of the Coldstream Guards and I had a parade-ground encounter that taught me a lesson. Never was a man better named. Picture the 18-man 512 troop, now sophisticated and hardened veterans of drill parades, expertly marching and halting as one, symmetrically wheeling, turning and rifle-bashing their way around the vast black tarmac acreage of Blackdown’s drill square, fearlessly and faultlessly responding to the stentorian commands of Sergeant Major Hayter.

‘By the left, quick march! Left, right, left, right, left, right, left.’

‘Squad ’alt!’

‘Quick march! Left, right, left, right, left, right, left. Aybout turn! Left, right, left, right, aybout turn! Left, right, left, right, LEFT TURN! Left, right, left, right, LEFT TURN! Left, right, left, right, RIGHT TURN!’

And who turned left? I did.

‘SQUAD ’ALT!’

‘Officer Cadet Walker come ’ere, SIR!’

(All Officer Cadets had to be addressed by NCOs as ‘Sir’, which was usually done with great emphasis and heavy irony.)

‘We got it all wrong didn’t we, SIR?’

‘Yes, Sergeant Major.’

‘Shall we show them how to do it properly then, SIR – just you and me?’

‘Yes, Sergeant Major.’

‘Right then. Officer Cadet Walker only. Quick March!!’

I think you’ve got the drift now and he had me sweating round the square performing obscure drill manoeuvres by myself for a solid 10 minutes. And the lesson it taught me? Listen out, stay sharp and don’t assume that everything is going to be as it used to be.

In spite of that I continued really to enjoy the drill sessions. There is something very satisfying about marching proud, swinging your arms high with your back straight and your head up, knowing that, as a unit, you look terrific. We were getting to be soldiers now!

Blackdown held no terrors like Corporal Coleman. I reached the required standard without interruption and, in October 1943, it was goodbye to 512 Troop at Pre-OCTU and hello to 115 Troop RAC OCTU at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, the most famous and historic in the world. Sandhurst, as it is known, has been the elite training centre for regular officers of the British Army since the early 1800s and, compared to Bovington and Blackdown, was relatively luxurious. When World War Two broke out it became the Officer Cadet Training Unit for Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) personnel only. We were quartered in the historic buildings and followed the long-established Sandhurst traditions and practices that had made the British Army so dominant and powerful over the centuries. I was immensely proud to be associated with and shaped by them and to be trained in such impressive surroundings.

Some 23 of us started in 115 Troop and six months later 18 of us reached the giddy heights of Second Lieutenant. Sandhurst was enormously enjoyable but it was also tough, because of the ever-present fear of failing what was a pretty demanding mental and physical regime. The whole thing was even more intense than Blackdown with major emphasis on determination, initiative and leadership. The Sandhurst assault courses had some fiendish elements. One of them required you to climb up a 40ft hill in full kit, run off the top of it on to a single narrow plank, clear a gap on to another plank, run across that, jump on to a third plank and then rush down the hill. I’ve seen strong men stuck with one foot on each plank and a 40ft drop beneath them, transfixed with fear and panic and unable to move. Being put into a room into which CS gas was pumped, but not being allowed to put on your gas mask until you had inevitably inhaled some of the filthy stuff was not a lot of fun either. Nor was having to negotiate pitch-dark shoulder-width underground tunnels while some joker dropped thunderflashes around you. However I made it, only to experience the supreme test of physical horror – a Welsh battle course.

It started at a Youth Hostel at Capel Curig, in Caernarvonshire, from which we set off to do infantry manoeuvres, sleeping rough and living off the country until we reached Britain’s highest mountain, 3500 ft Mount Snowdon. I was the one carrying the 2in mortar and my abiding memory of the whole week was the Troop Sergeant’s non-stop screaming to ‘double up, the man with the mortar!’ But after days and nights of marching, digging slit trenches, attacking seemingly invulnerable positions, sleeping in pig sties and other fun things, we finally got to the lower slopes of Snowdon.

‘I want 10 volunteers to climb to the top with me,’ said Captain Marsh, our course commander. And, of course, dead keen, I volunteered. It was hard, but we went up a comparatively easy route and had a double bonus at the end. Apparently, it is very unusual to get an uninterrupted view from the top of Snowdon but ours was as clear as a bell and you could see for miles in every direction – magnificent. As soon as we were done we were bussed back to the hostel we had started from – those who hadn’t volunteered, in the belief that they would get to the hot baths and beds before us, were made to march there on a compass bearing that got them back, by way of rivers and very rough country, at four in the morning. My respect and admiration for what was known in World War One as the ‘PBI’ (Poor Bloody Infantry) had increased tenfold and I knew now why it was that I had wanted to serve in tanks – you didn’t have to walk and had a roof over your head.

The camaraderie at Sandhurst was wonderful; the tank driving and commanding and the gunnery fabulous; and the occasional evenings in the pub were great. Even the Church parades were very special because they were held in the RMA Chapel: an immensely dignified and very moving scene of military tradition and magnificence. But of course all good things come to an end. For me that was on 8 April 1944, my passing out day, with all the moving pomp and circumstance at which the Army is so accomplished. My parents and friends were there and the salute was to be taken by that great American General Dwight Eisenhower, Commander in Chief of the Combined Allied Forces which, in just two months’ time, would be landing on the coast of Europe to commence its bloody liberation.