По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

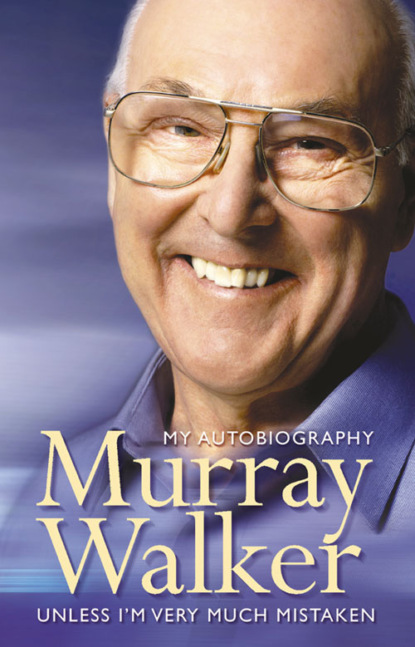

Murray Walker: Unless I’m Very Much Mistaken

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Charming!

Tom Peters got a message one day to go and see the boss, Bill Lloyd. A few minutes later he was out the door – fired – and was last seen walking down Buckingham Avenue. I wasn’t very far behind him, but not for the same reason. McCann Erickson, the world’s largest advertising agency, had made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. Apart from my work with Aspro, I was now some eight years into my broadcasting career and becoming well known for my motor sport activities. Peter Laufer, then boss of McCanns, reckoned I would fit in well on an automotive account and doubled my salary to £2000 a year.

Aspro had got me up to speed in the proprietaries business – selling to chemists, newsagents, filling stations and every other conceivable type of outlet – but now I was back in the motor world in which I had started with Dunlop, but this time trying to generate demand for motor oil, a product with as little interest for motorists as tyres. McCann handled the mighty Standard Oil business worldwide, with Esso Extra petrol being the lead product. This alone made a lot of the agency’s money and Jack Taylor and I, the account executives, would stagger down to Bernard Allen, the Esso Advertising Manager, with not one but 15 campaign approaches in the hope that one of them would ring the bell. ‘Why don’t you show me the one at the bottom?’ he would say. ‘That’s the one you want to sell me, isn’t it?’

This was before the days of motorist incentives at filling stations and catchy, memorable advertising was the name of the day. For petrol the ‘Esso sign means happy motoring’ television commercials, with their singing cartoon petrol pump globes and bouncy jingle, worked a treat but Esso Extra Motor Oil was something else. Oil, like tyres, is a necessary evil. No one says, ‘Hey, come and see the stunning new Dunlop tyres on my car,’ or ‘Wow, I feel like a million dollars now my car’s filled with Esso Extra Motor Oil.’ Or if they do, they need their brain testing. It was hard going.

It was at this time that things came to a head with a girl named Paddy Shaw. I was now 34 years old and still not married. I was certainly interested in girls and I’d had my share over the years, in the army at home and abroad, at Dunlop and at Aspro, but it has to be someone very special indeed if you are to spend the rest of your life with her and it just hadn’t happened. Except, maybe, with Paddy.

I often wonder if my parents, and especially my mother, had more of an influence on my life than other people’s do. I was certainly very close to and affected by my mother and father and what they thought. When my father had been a member of the Norton racing team in the 1920s one of his team-mates was a genial Ulsterman named Jimmy Shaw and they formed a very close friendship, as did my mother and Jimmy’s wife Ethel. The Shaws ran a garage and motor business in Upper Queen Street, Belfast, were the Ulster distributors for Triumph and Lea Francis Cars (for whom Jim used to race) and made a lot of money. Jimmy got the customers: Ethel did the rest. They had a son, Wesley, and five daughters, Maureen, Joan, Paddy, Fay and Barbara. My parents and I used to go and stay with them, and they with us, and as I grew up I progressively fell for first Maureen, who married an American army Captain and went there to live, and then Joan, who married Terry Bulloch, a BOAC Captain. So then it was Paddy and this time I felt it was for real – so much so that when Jimmy and Ethel sold the business and the whole family went to live in the States I felt I had to pursue Paddy there and resolve things.

This happened between my leaving Aspro and joining McCann. Paddy was working at Yellowstone National Park and when the snows came and the park closed down for the winter I flew to Billings, Montana, to drive with her to her winter apartment in La Jolla, California. It was a four-week trip in a Chevrolet Bel Air, by way of Yellowstone’s Grand Canyon and its world-famous geyser ‘Old Faithful’, the wonderful sights of Salt Lake City, across the Utah Salt Flats to Virginia City and its extinct silver mines to Reno, over the Sierra Nevada to Lake Tahoe (just a few log cabins there in those days), across the Oakland Bay Bridge to San Francisco and on to Monterey and La Jolla, which, like Lake Tahoe, was totally undeveloped and an idyllic spot. It was a great trip and long enough for me to find out that it wasn’t going to work out between Paddy and I and that it was better to return to Europe and start my new job.

With all the wisdom of hindsight I truly think that a lot of my feelings for Paddy were brought about by huge unspoken pressure from the Shaw family and my parents who felt that their long-standing friendship should, naturally, result in a marriage between one of the girls and myself. There were regrets at the time, of course, but I was later to find in Elizabeth a woman I fell for with no reservations and now, after more than 40 very happy married years together, I know it was all for the best.

I was at McCanns for two years but I have to say that it made very little impression on me. The people were fine and so was the client. The broadcasting was going well and I was still living at home with my parents, contented and seeing no reason why I should do anything else but I felt once again, as I had at Aspro, that I had to move on. Part of the problem was that there seemed to be no connection between the advertising work I was doing and the sales of the product. I had kept in touch with all the friends I had made at Masius, which, as an agency, was booming, and on impulse I phoned Jack Wynne-Williams. He invited me over to come and talk and, sitting in his cosy office overlooking St James’s Square, we did the deal that was to take me to the end of my business life.

CHAPTER FOUR Starting at Masius (#ulink_eff66d8c-b27c-5b69-842e-366c106dd614)

The move to Masius wasn’t easy. Aspro and Esso had been as different as chalk and cheese and now things were as different again with my new clients at Masius – the Mars Confectionery and Petfoods companies. These were wholly owned by Forrest Mars, an American with a complex personality and an unusual business philosophy. Forrest didn’t think or act like other people; he was a one-off maverick and even his own father, Frank Mars, who owned a hugely successful confectionery business in America, found him too much to stomach. Legend has it that he gave his son $30,000 (a massive amount of money in those days) plus the rights to use the recipe for Mars Bars (named after the owner, not the planet) anywhere outside America, and told him to ‘germinate your arse to the other side of the Atlantic.’ Forrest set up shop in Slough in 1932 and started his business with the Mars Bar which is still, of course, very much one of Britain’s leading brands.

In those tough early days Mike Masius would go down to Slough every Saturday for Mr Mars to tell him how much money he could have for advertising the next week. ‘Mars are marvellous!’ was the rather plonking claim but great things start small and under Forrest’s distinctive and forceful leadership the business became one of the most successful the world has ever seen, eventually taking over that of his late father and, for a long time, being the largest privately owned company in the world. It began with the Mars Bar, led to other brands like Milky Way, Maltesers, Bounty, Galaxy, Spangles and Opal Fruits, and then to the start of an entirely new and innovatory product – canned petfoods.

So in some ways for me this was a similar situation to Aspro: popular, low-cost products with mass distribution through grocers, confectioners and tobacconists and with tough and aggressive competition from talented and experienced organizations like Cadbury, Nestlé and Rowntree. But the Mars advertising philosophy, enthusiastically embraced and promoted by Forrest himself, was entirely different from anybody else’s, being incredibly hard-nosed and product-based in comparison with anything I had experienced before. So I had a very steep learning curve amidst some extremely sharp and demanding people, but at last I felt I was where I wanted to be and I relished the stimulating atmosphere.

Mars were based, coincidentally, in the same road and trading estate in Slough where I had worked with Aspro, while Petfoods were at Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire. Both worked to the same unique management philosophy laid down by Forrest Mars: everyone clocked in and out, even the Managing Director; rather than receiving a bonus for being punctual you got less if you were late; only the man at the top had a private office, and his had no door; everyone ate in the same canteen. There were no status perks, no company cars, and no sports and social club.

In addition, Mars executives were not allowed to accept gifts from suppliers – no matter who they were. Jack Wynne-Williams was a very keen shot and used to return from weekends in Suffolk with his Pontiac station wagon full of birds, which his secretary, Mona Fraser, then sent to selected clients and agency people. One day she sent some pheasants to ‘Mac’ McIntosh, the boss at Slough, who returned them with a very nice note, the gist of which was that Mars company policy prevented him from accepting gifts from suppliers, which of course Jack was.

Jack phoned him. ‘My god, Mac, do you think that if I wanted to bribe you I couldn’t do better than a few pheasants?’

‘Of course not, Jack, but you miss the point. If I accept the pheasants from you how could I stop my buyers from accepting a Jaguar?’

The company had a very generous pension scheme and while everyone was threatened with a drop in salary if the company’s turnover decreased by £1 million (it never did), they also got a raise each time it went up by that magical figure. There was an occasion at Petfoods when hitting the next million required a railway container of product to leave the factory limits that day – at a time when no locomotive was available. People just rallied round and pushed it out. Everyone was paid far more for their job than they could get anywhere else and the result was that the Mars companies not only got the best people but kept them. They had a reputation of being heartless hire-and-fire organizations but this wasn’t true. They were awesomely efficient with operating systems way ahead of their time, knew who they wanted and got them, but they were no more ruthless with their people than any other decent organization. Once you were there it was actually quite difficult to leave because you could only do so by getting a job at least two levels higher and that was unlikely.

Knowing this, during my time at Aspro I had applied for a job as Brand Manager at Petfoods and after two long individual interviews with the Personnel Director and Personnel Manager was told to report to the Washington Hotel in London’s Curzon Street – and be prepared to be there for 36 hours. When I arrived I found I was one of the last six of several hundred applicants. After socializing at three meals, more individual interviews, wire puzzles, group discussions, debates and psychological tests which lasted well into the second day, I staggered home. The last thing required of us was to have a 60-minute debate on a subject of our own choosing – ‘But not, Gentlemen, anything religious or political for obvious reasons.’ There was a rather thick Scotsman amongst the six of us who had been opening his mouth and putting his foot in it the whole weekend and, obviously eager to demonstrate his leadership qualities and quick thinking, he leapt in with, ‘I propose that we discuss the significance of the Roman Catholic Church in today’s world.’ As one, hardly believing our luck, the rest of us said, ‘Isn’t that religious?’ So then there were five. One then quietly said, ‘Let’s talk about the pros and cons of capital punishment.’ It was a chap called Neil Faulkner. He was head and shoulders above the rest of us, got the job, had since become the man most likely to succeed at Petfoods and was now my client contact at Melton Mowbray.

The way Mars and Petfoods evolved their advertising was just as challenging as their personnel selection. They were the first in the UK to work to the USP philosophy, which involved intensive research to find out what potential buyers wanted from the product and from that the creation of a Unique Selling Proposition (not Unique Sales Point as so frequently incorrectly described). Hence, among the brands I worked on, ‘PAL – Prolongs Active Lije’, ‘Opal Fruits – Made to make your mouth water’, ‘Liver-rich Lassie gives head to tail health’ and ‘Trill makes budgies bounce with health’. In my broadcasting life after I had left the advertising world, I was constantly described in interviews as the originator of one of the greatest USPs of all time – ‘A Mars a day helps you work, rest and play’ – but I certainly wasn’t, unfortunately!

I was like a fish out of water when I joined Masius. The total billing was less than £5 million but in the years to come it was to rocket to stratospheric levels. I had joined at just the right time but I didn’t realize my good fortune – I was far too busy struggling to keep afloat in this fast-moving organization and trying to give the impression I knew what I was doing: learning the two companies’ very specialized operating procedures, working out how best to cope with their very tough and competent but very human executives and implementing what they wanted, or thought they wanted, inside the agency with the research, art, copy, TV, media and marketing departments. All businesses have their internal rivalries but we had them considerably less than most. We were all working for a benevolent dictator whom we liked and respected. The ‘Grocers of St James’s Square’, as we were sneeringly referred to by a lot of advertising people who were later to eat their words, made dynamic progress but the whole business nearly came to a standstill very soon after I joined it.

At the time, Forrest Mars was trying to get Masius to merge with the Ted Bates advertising agency organization in America, but Mike Masius and Jack Wynne-Williams were steadfastly refusing. Just a few weeks after I had joined we were told that Forrest Mars was coming in on the Saturday morning to collect a pair of shoes that he had had repaired (most people with his income would have bought themselves a new pair but Forrest wasn’t like that) and that we were all to be on parade, sitting to attention at our desks, in case the great man wanted to address us. Which is where I was when my phone rang. It was Jack.

‘Murray, Mr Mars is in reception. Would you bring him to my office?’

There was just one person in Reception – a balding, middle-aged chap wearing a very ordinary blue suit and one of those strange American homburg hats with a wide ribbon and the brim turned up all the way round. This can’t be him, I thought, but there’s no-one else here so it must be.

‘Mr Mars?’

‘Yes, son.’

‘Welcome to Masius, Sir, and do come this way!’

Mr Mars not only collected his shoes but, after again failing to persuade Mike and Jack to merge with Bates, demonstrated his displeasure by announcing that he was going to stop advertising his major cat food brand, Kit-E-Kat, and also transfer the top-selling Spangles to another agency.

Those two brands were vital to us and we were very badly hit but Jack just said, ‘There’s only one way to recover – go out and get more business.’ Which we did, and prospered. The happy ending was that Kit-E-Kat, bereft of advertising support, lost sales heavily and the advertising was restored at an even higher level less than a year later.

An example of how Forrest Mars’ mind worked differently to other people’s was his question about the agency’s very successful use of the world-famous American cowboy film star Hopalong Cassidy to promote Spangles.

‘How much is this guy Cassidy paying us?’ he asked.

‘Er, it’s not like that, Mr Mars, we pay him actually.’

‘Why’s that? Just look at all the publicity he gets from us!’

True enough, but needless to say Mr Mars wasn’t daft. He did the things he did and acted the way he did to provoke people into thinking. And it worked.

In those days British pets were fed household scraps and the marketing objective was to persuade the owners to substitute canned Petfoods products. This wasn’t easy when the household scraps cost nothing and PAL, Lassie, Kit-E-Kat and the rest were not only regarded with suspicion but had to be paid for. Nor was it easy to get a doubting trade to stock them, when it was generally believed the contents were mainly factory floor sweepings. I used to make shop calls with Petfoods sales reps and we would solemnly open a can of Kit-E-Kat before a buyer’s cynical eyes and eat some to show how good and wholesome it was. That usually won them over and so it should have, for at the time it was mostly whalemeat, which most of us ate during the war with no ill effects. Eventually we won the day, for who feeds their pets household scraps these days? It says a lot for the vision and determination of Forrest Mars.

One of my brands was Trill, the packeted budgerigar seed, and on a visit to Melton Mowbray I was presented with a unique problem by Tom Johnstone, the Petfoods Marketing Director.

‘With Trill we have over 90% of the packaged budgerigar seed market and we very much want to expand what is an extremely profitable business,’ he said.

‘Yes, Tom, of course.’

‘In a static market, the obvious thing to do is to buy our competitors but we don’t want to do that because if we did we could well run foul of the Monopolies Commission.’

‘Yes, of course, Tom.’

‘So what we have to do is to increase the budgerigar population and then we’ll get 90% of the extra business.’

‘Yes, of course, smart thinking!’

‘So that’s what we want you to do, Murray – come up with ideas of how we can do that.’

‘YOU WHAT?!’

‘Off you go then and we’d like your proposals within a week with full advertising and budgetary recommendations.’

Back I went to the agency, got everyone round a table, outlined the brief and sat back to worry. Two days later we were all back together.

‘Here’s the deal, Murray. Most people have just the one budgie, right?’

‘Right.’

‘Well, what we want to do is to create a guilt complex by promoting the belief that an only budgie is a lonely budgie and thus motivating their owners to go out and buy another one.’

‘You what?’