По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

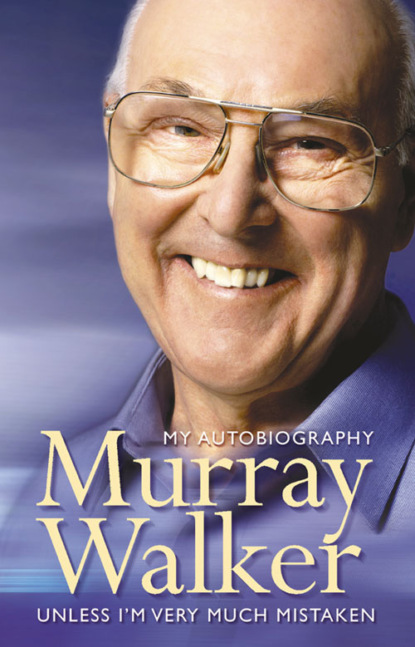

Murray Walker: Unless I’m Very Much Mistaken

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

On to that magnificent parade ground in front of the Old College, then, marched the entire Sandhurst contingent in proud formation, with heads held high, arms swinging and boots resounding to the drum beat and stirring military marches of the band that preceded them. I certainly felt emotional – even 57 years on I can still feel the excitement and pride. I was now Second Lieutenant Walker, Royal Armoured Corps, wearing the coveted black beret and ready to go to war from a sealed camp at Manningtree, near Harwich, the gateway to the Continent.

My recollections of Manningtree are dim and my recall of the ship I boarded dimmer, but the trip itself was smooth and straightforward. It took quite a long time: we turned right after Harwich and headed south through the Straits of Dover for the Mulberry Port at Arromanches, a wonderful example of British initiative and enterprise. To bypass the heavily defended French ports of Le Havre and Cherbourg, enormous concrete caissons were prefabricated in Britain and towed out to France on D+1, 7 June, to create a brand new port almost the size of Dover. When we were put ashore the whole area was a hive of khaki-clad activity with tanks, trucks, guns and all the other bric-a-brac of warfare flowing out of ships and on to the shore along the floating roadways. I wasn’t there long because I was rapidly assigned to a tank transporter column that was to make its way to Brussels. And what a journey that was. As the lengthy convoy of enormous American White tractor units with their massive trailers, each carrying a Sherman tank, slowly churned its way through the recently liberated French countryside into Belgium we got an enthusiastic reception from the population, still euphoric after their liberation from ‘les salles Boches’.

I was very lucky to join the Royal Scots Greys, even if I was rather a round peg in a square hole. First raised in 1678, the regiment was one of the foremost in the British Army and had fought with great distinction in Palestine and in General Montgomery’s magnificent Eighth Army from the Western Desert to Tripoli. It had taken part in the invasion of Italy, landed in Normandy, fought its way through France into and out of Belgium and was now at Nederweert in Holland where I joined it.

So, as a young, untried and totally inexperienced new boy I was becoming part of one of the toughest, most case-hardened fighting units of all. When I reported to the tent of the charming Major Sir Anthony Bonham he said to me, ‘Welcome to the Regiment, George, we are glad to have you with us.’

Somewhat embarrassed, I said, ‘The G is for Graeme, actually, Sir, but my friends call me by my second name, which is Murray.’

‘Oh,’ he replied. ‘I thought Murray Walker was a hyphenated, double-barrelled name.’

I had the feeling that he was rather disappointed that it wasn’t, because that’s the sort of regiment it was: very Cavalry, very regular, officered by moneyed County gentry, many with Scottish connections, who had been educated at the very best and most expensive schools and who had known each other and fought together for a long time. I was and still am immensely proud to have been a Greys Officer and to have fought with them but I certainly felt as though I was in a club of which I was not a natural member.

Major Bonham told me, ‘You will be responsible to Sergeant McPherson, Murray.’

Sergeant? What the hell does he think this Second Lieutenant’s pip on my shoulder is – confetti?

‘I know what you’re thinking,’ he said. ‘Fresh out of Sandhurst I expect you think you’re God’s gift to the British Army, but you should know that McPherson has been with us since Palestine. He has forgotten more about fighting and the way the Regiment does it than you’ll ever know and when he says you are capable of commanding a troop you will have one.’

He was, of course, absolutely right. So I watched and listened and before long I got my own troop. A few days later we moved to the island between the Waal and Neder Rijn rivers north of Nijmegen where I had my first experience of sentry-go, Greys style. Up all night standing in the Sherman’s turret, with the Germans on the other side of the river, thinking that every sound you heard was one of them creeping up to blast you to perdition with a Panzerfaust. This was shortly after the airborne forces’ foiled attempt to capture the bridge over the River Maas at Arnhem and to launch the 21st Army Group across the Rhine into Germany. From our positions on the other side of the river we could see parachutes and supply containers for the beleaguered airborne troops hanging from the trees. One night I had to transport ammunition on my tank to troops of the American 101st Airborne Division. It was not a job I relished as, silhouetted against the sky, we slowly felt our way along the dark and narrow road with no turn offs. There was a great deal of heavy and very messy fighting at this time, clearing river banks, woods and other difficult areas and, as ever, the Regiment came out of it with great distinction.

During the actual fighting, we tried to rest whenever and wherever we could – in the vehicles, in barns and even in Dutch homes. On one occasion though, when I was seeking billets for my troop, the door was opened by a completely bald woman whose head had been shaved by revengeful villagers because she had collaborated with the Germans. The time we spent in our winter quarters was really good. I was billeted in a very comfortable Dutch home in Nederweert with the Regimental Quartermaster, Captain Ted Acres, a dry, exact, pedantic and incredibly efficient chap, and Fred Sowerby, a blunt and cheerful Yorkshireman who ran the light aid detachment. It was Fred who refused to help me out of a difficult situation when I forcibly removed the windscreen of my regimental Jeep. I had done so in a moment of madness when driving across an airfield while a B17 bomber was starting to take off. The chap who was with me said he’d bet I couldn’t catch it. I not only did so but clipped the back of its tailplane with the top of my windscreen. ‘You did it, you silly young bugger,’ said Fred, ‘so you can live with the consequences!’

In the evenings though, when the day’s training schedules, joint manoeuvres with the infantry, gunnery practice and tank maintenance tasks had been completed, Ted, Fred and I could relax in front of a roaring fire catching up with the very welcome mail from home and listening to the American Forces Network. Frank Sinatra was the man, Peggy Lee was the woman and the big bands of Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Woody Herman, Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller were and still are my passion.

In the middle of February 1945 the Greys’ winter rest period ended. The long-serving personnel had returned from their UK leave and the Regiment was refurbished and refreshed – just as well, for the end of winter heralded some of the bloodiest fighting of the Second Front. The war had now surged up to the very borders of Germany at the Reichswald Forest and the mighty River Rhine. The Greys were heavily involved, co-operating closely with the infantry, and the going was very tough indeed with the Germans resisting every inch of the way with anti-tank guns, rivers, ditches, snipers, blown bridges and Panzerfausts. Their homeland was now being directly threatened and that added extra steel to their resistance. It was here that I had one of the most emotional experiences of my life.

Times arose when we had to let other units leap-frog through our positions so that we could refuel, take on fresh ammunition and eat. You stopped by the supply vehicles and then there was a flurry of activity: humping five-gallon jerricans up to the engine compartment and sloshing petrol into tanks, passing shells and ammo boxes up into the turret, maintenance work – a sort of tank pit stop. Sitting on the turret with my legs dangling inside while my troop was on its way to one of these, I saw a group of four men in army uniform and idly thought that one chap looked just like my father. As we got closer I realized to my amazement that it was my father: he may have been in battledress and wearing a khaki beret but his stance was unmistakable and to clinch it he was smoking his inevitable pipe. At the time he was editor of Motor Cycling, and had got himself accredited as a war correspondent with the express intention of finding me, which he’d done. Needless to say it was wonderful to see him but there wasn’t any time for more than a short conversation because I had to get back into action.

This all happened close to a place called Udem, near the towns of Goch and Kleve which had been completely obliterated by over a thousand bomber raids. I remember having to get out of the tank at one point during the night and thinking that I must be in Dante’s Inferno. The road was blocked by rubble, houses all round me were ablaze, there were dead bodies lying on the ground amid a nauseating smell, bemused cattle were wandering about, people were shouting, guns firing and there was the constant worry that somewhere up the road was an 88mm or Germans to let fly at you with a Panzerfaust. With V1 rockets aimed at Antwerp soaring over us, we advanced despite the most stubborn resistance by Panzers and elite Paratroops. The Reichswald was cleared and on 24 February 1945 we crossed the border into Germany.

It is difficult to find the words to express my emotions as I saw the crudely signwritten board saying, ‘YOU ARE NOW ENTERING GERMANY’. Since 1939 Britain had been subjected to defeat after defeat in Europe, Africa and the Far East. Our towns and cities had been bombed and torched with incendiaries. Countless thousands of men and women had been killed, maimed and injured on land, sea and in the air and Hitler’s U-boats had done their best to starve us out. Standing alone, Britain had been on its knees but it had fought back and now, with the might of America at its side, it was winning.

The British Army’s part of the Eisenhower/Montgomery master plan called for the crossing of the Rhine and then a mighty surge towards the Baltic. Now, after the bloody night attacks using ‘artificial moonlight’ from searchlights, we were on the west bank of the Rhine near Xanten. Looking across its mighty width, it seemed impossible to cross but we knew that it was just a matter of time. On 23 March there was a 3300-gun artillery bombardment of the far shore and beyond which must surely have been one of the most intense in military history, and on the following day the 6th Airborne Division swept into action. I simply could not have imagined what it would be like, and if I hadn’t seen it would never have believed it. As the gathering roar grew louder and louder, I stood beside my tank looking up at a vast fleet of hundreds of aeroplanes towing gliders containing troops and equipment. With no opposition from the Luftwaffe, they reached their targets, cast off their gliders and returned for more. It was the most amazing demonstration of military might and how Britain had clawed its way from the brink, rebuilt its forces and turned the tables on its enemy. But it wasn’t all euphoria: at one point, to the horror of the forces below, a Tetrarch reconnaissance light tank emerged from its glider hundreds of feet above us and plunged to the ground with its crew still inside. What had happened I do not know, but the story was that with the engine running for a rapid exit, the driver had dropped the clutch while still high up in the air. Whatever the reason, it was a terrifying sight.

On 25 March we crossed the Rhine. Unlike Arnhem, the air drop had been a total success and a bridgehead had been established. German forces were still holding out in Holland, to our left, and the Ruhr, to our right, but between them the way was now open for a charge to the River Elbe and Hamburg. But there was still a lot of bloody conflict before that could happen. Progress was slow and painful. At one point there was particularly bitter resistance from the German Second Marine Division and I remember standing over one of them, who was clearly dying, with a drawn pistol in my hand in case he was bluffing and tried some desperate move.

After virtually continuous fighting, during which I liberated a fine pair of Zeiss binoculars from a German 88mm gunner who had been trying to wipe us out, we reached the crucial River Elbe, south of Hamburg. In a mammoth military traffic jam pouring across the newly constructed army bridges, the mighty Elbe was crossed and now our momentum was unstoppable. With the Russians advancing rapidly towards Berlin from the East and the combined forces of the West pressing forward from the other direction, the Germans were in a vice and their resistance melted. With vivid and bitter memories of the Russian campaign uppermost in their minds, the last thing they wanted was to be captured by Stalin’s men, merciless and eager for retribution and revenge. Things became very political as it was vital to the Allies that their forces reached the Baltic before the Russians. The key was Lubeck. ‘Get to Lubeck first!’ was the stirring order given by the War Office to the 21st Army Group. The Greys and the 6th Airborne Division were instructed to head for Wismar on the Baltic coast, and we went for it. It was an incredible experience. At the rate of some 5000 troops an hour, the German army was heading west as fast as possible to avoid being captured by the Russians, while on the same single carriageway road we were hammering east absolutely flat out. With the British and the Germans going their different ways just feet away from each other there was no fighting, no acknowledgment even. At one point our headlong gallop was brought to a halt by the sheer weight of traffic and, sitting on the top of the turret eating a tin of Spam, I found myself looking down on to a vast open Mercedes-Benz staff car containing four obviously high-ranking German officers. It was hardly the time, place or occasion for a cheery chat: we studied each other dispassionately and not a word was spoken. Then the column moved on, so did they and that was the last we saw of each other.

On 2 May 1945, after an incredible 80-mile dash in one day, the Royal Scots Greys reached Wismar to become the first unit of the British Army to link up with the Russians – in the form of a captured German BMW motor cycle and sidecar carrying an officer on the pillion and a woman soldier in the sidecar, accompanied by a couple of American White scout cars and another mixed bunch of soldiery. The war was over.

The Greys did not stay in Wismar long. At the end of May 1945 we moved to Rotenburg, between Bremen and Luneburg, where I was given a special job to go to the Philips factory in Eindhoven, Holland to collect a load of radios for the Regiment. I was to be allocated a truck and to find my own way. But I wasn’t exactly overjoyed when I found the truck was a Morris-Commercial 15cwt that the Germans had captured from us at Dunkirk in 1940 and had been using all through the war.

It was in running order but not in the best of shape, to put it mildly. However, off I set with Trooper Doug Taylor (my personal servent in the army) to lumber back through Hamburg, Bremen, Osnabruck and Munster, retracing our steps amid refugees, columns of troops, tanks and B (wheeled) vehicles as Europe started to reorient itself after over five years of bloody conflict. The gallant old Morris did a fine job and didn’t let us down, although it certainly took its wheezy time getting there. But when we got to Eindhoven the news was not good.

‘The radios are not ready,’ we were told. ‘Please come back in three days.’

Well, there wasn’t much to occupy us for three days in war-torn Eindhoven so we decided to go to Brussels – plenty going on there. I had a Belgian girlfriend in Brussels from my time at Villevoorde earlier in the campaign, so we fired up the willing old Morris again, and headed off. This was strictly forbidden, of course, for I had no authority to go there and very nearly ended my army career by doing so. We left the Morris in a military park and three days later, after a great time in the big city, Doug and I returned – but there was no sight of the Morris. Eventually, in desperation, we asked the Sergeant in charge if he could help us. ‘Ah, yes, Sir,’ he said when he saw the receipt. ‘We were a bit suspicious about this vehicle in view of its age and when we checked we found it wasn’t on the Army records so it has been impounded.’

Oh my God. Stark panic. I was in Brussels where I wasn’t supposed to be, I’d been there for three days without authority, my truck had been impounded, I hadn’t got the radios and I had no way of getting back to the Regiment in far off Rotenburg. I could see the court martial looming. There was only one thing to do then: find the Town Major, make a clean breast of it and cast myself on his mercy. ‘You’ve been a bloody fool, haven’t you?’ he said. ‘Well, we’re all human and it is going no further. Off you go and the best of luck.’ And that, thankfully, was the end of that.

During our time at Rotenburg any fleeting thoughts I may have had about signing on with the Army as a regular soldier evaporated and I decided that the life was not for me. Things became more routine with the fighting over. Now a Lieutenant, I was promoted to Mechanical Transport Officer, which meant that I was in charge of all the Regiment’s B (wheeled) vehicles and answerable to the Technical Adjutant who was responsible for all the Regiment’s vehicles. This, of course, was right up my street.

During this time a friend of mine, Peter Johnson, returned briefly to the UK, sharing a cabin with a couple of British Infantry officers. They were discussing what loot they’d brought back with them. Peter mentioned he’d a German officer’s revolver and a Nazi flag.

‘Look at this then,’ they said, opening a suitcase full of jewellery and gold ornaments.

‘God almighty!’ says Peter. ‘Where the hell did you get all that lot?’

‘Well, we’re first in anywhere and we go straight to the jewellers’ shops.’

It was thieving of course but anything was fair game in those times. For the record I came out with my binoculars, which I still have, a P38 revolver, which I handed in during the arms amnesty, an enormous Swastika flag and a German officer’s knife with ‘Gott mit uns’ engraved on its blade. Funny that. We thought he was with us.

I was again promoted, in February 1946, to become the Technical Adjutant and to start a running battle that could have ruined my life. It’s a long story so a bit of background might be helpful. The Regiment was reverting to its normal peacetime ways, which were totally foreign to me as mine were to them. For instance, I started a motor-cycle club for the whole of the 4th Armoured Brigade and spent a great deal of time organizing trials and scrambles, sourcing machines to be used for competitions and even working with the Regimental Fitters building bikes, none of which were usual activities for a Greys officer and they were undoubtedly regarded as unacceptable behaviour.

Amid this increasingly fraught situation, I should have been promoted long before to the War Substantive rank of Captain. It wasn’t happening, though, and I was getting fractious. I am hard to rouse but was outraged that I was not being given the rank, income and status that went with the job. Eventually I was grudgingly given the rank of Local Captain but not the money that went with it or any promise of permanency, which, if anything, made me even angrier. To top that, they tried to cancel the home leave that I’d previously been granted, and which I’d applied for months in advance so that I could attend the first post-war motor-cycle race meeting in the fabled Isle of Man, the Manx Grand Prix. They claimed it was cancelled for disciplinary reasons.

Now the battle was well and truly on. Thanks in part to my father’s influence I got my leave and had a wonderful time in the Isle of Man, but when I reported back to the Regiment in Luneburg it was to find that an adverse report on me had been submitted which recommended that I be reduced to the ranks because I was ‘unreliable, unsuitable, untrustworthy and a bad example’. My back was up against the wall now for if the recommendation was accepted, the Dunlop Rubber Company (for whom I’d recently had an interview for a job after I left the army) would certainly have thought it a bit odd that the Captain they had interviewed next appeared as a Lance Corporal, quite apart from the loss of self-respect the demotion would have caused me. Fortunately though, army rules being what they are, I was allowed to submit a written response. Knowing that my future literally depended on it, I sat down and gave it my very best shot – five closely typed foolscap pages.

For most of my time with the Regiment it had been part of the famous 4th Armoured Brigade, commanded by one of the most outstanding men it has ever been my privilege to meet: Brigadier R M P Carver CBE, DSO, MC. He was young – in his very early thirties – had a wonderful personality, and was a superb example of all that was the very best in the British Army. He was the sort who would suddenly appear on the back of your tank in the middle of some very unpleasant action and ask you why the hell you weren’t further ahead. And now he was to rescue me from this situation that could well have blighted the rest of my life. He came to the Regiment to interview me and told me that my response had been accepted but that it was clearly impossible for me to continue with the Greys. I could not disagree with him for had I stayed the atmosphere would have been intolerable. So you can imagine the relief and pleasure I felt when he went on to say that I was being transferred to become Technical Adjutant of the recently formed British Army of the Rhine Royal Armoured Corps Training Centre at Belsen, with the full rank of Captain. So I had won without a stain on my character, but it is a battle I would far rather not had to have fought. I was and still am mighty proud to have been able to serve in and fight with such a wonderful regiment as the Greys, but only sorry it ended the way it did.

So to the BAOR RAC Training Centre at Belsen. Not the Belsen of concentration camp notoriety? Yes indeed, but very different by the time I got there in October 1946. The hideous installations of the Nazi death camp had been destroyed, the bodies buried and the thousands of displaced persons moved to other locations. Belsen became Caen Barracks, which had a driving and maintenance wing, gunnery and wireless wings, a tactical wing and its own AFV ranges to provide short-term courses of just about every conceivable type. ‘Officers,’ says the brochure which I still have, ‘should bring their own sheets and pillowslips and may bring their own batmen [personal assistant] with them if they wish but German civilian servants can be provided by the Centre if necessary. Facilities are available for riding, shooting and fishing, football, rugby, hockey and swimming.’ A good place to finish one’s army career then and a dramatic contrast to the utterly unspeakable place it had formerly been.

The wheel had gone full circle for me. I had started my army career as a humble Private at the home of tanks, Bovington, and here I was finishing it with greatly enhanced status at Bovington’s German equivalent. The work was enjoyable and satisfying, the accommodation was good and I had the opportunity for local leave. On one occasion I went to Hamburg to stay at the Officers’ Club, which was located at the old Atlantic Hotel, one of the finest in Europe. It was surprisingly undamaged by the many RAF raids, but around it hardly a single complete building stood, however far you looked and in any direction. I remember thinking that there was no way that it could ever be rebuilt, but go there now and you wouldn’t think that there had ever been so much as a broken roof tile.

I started to get involved with the motor-cycle racing world again at Belsen. Germany, a centre of motor-sport excellence before the war, was already striving to recreate its racing activities but, banned from international participation as it was and with the country flat on its back, this mainly took the form of enthusiasts talking and planning for what might be. One such group was the Brunswick Motor Cycle Club, right on the east/west border, who got to hear of my existence and invited me to become an honorary member. It was led and inspired by Kurt Kuhnke, who had raced one of the incredible supercharged two-stroke works DKWs before the war. I spent several very enjoyable evenings in their company talking racing and bikes. Just a few months earlier I had been doing my best to rid the world of these people in the sincere belief that they were the ultimate evil but now here I was socializing with them about a common interest. It is indeed a funny old world – a world that was again about to change dramatically for me as, at the end of May 1947, I boarded the ship for Hull where I was to swap my khaki uniform for my post-war civvies.

CHAPTER THREE A is for Advertising (#ulink_d8a4f227-7cc9-592f-9760-2968f0675a63)

It was the summer of 1947 and I found myself back home again, aged 23, at ‘Byland’, Private Road, Enfield, Middlesex with my mother and father after over four years in the army. A very pleasant place to be, too. I had made another sparkling appearance at Fort Dunlop and, on the back of my Dunlop scholarship, had landed the job of Assistant to C L Smith, the Advertising Manager of the Company’s major division, the Tyre Group at Fort Dunlop – starting immediately. So my stay in Enfield was short-lived, and it was off to Birmingham and my digs with the Bellamys in Holly Lane, Erdington.

I didn’t find it difficult being a civilian again because I guess I had always been one at heart, much as I had enjoyed my time in the army. But this was certainly different. Every morning I set off to ‘The Fort’, walking the mile or so to the factory, and spent the day ministering to CL’s needs. He was a kind, if rather pompous, man who dressed immaculately and spoke with a plum in his mouth. He was easy to work for, but I cannot say that the job was overly demanding. For doing it I was paid the princely sum of £350 a year (roughly the equivalent of £11,000 today), so I wasn’t heading for an early or wealthy retirement, but I enjoyed myself.

I often socialized with Dunlop’s charismatic Competitions Manager, Dickie Davis – a great character, manager and salesman and also an accomplished pianist, who loved to entertain his mates by playing the joanna in the bar, surrounded by happy people and with a row of gin and tonics on the upright. I once arrived in the Isle of Man for the TT races and, straight off the boat, went to the Hotel Sefton where he was staying. ‘Get up, Dickie,’ I said to the recumbent form in his bed, ‘it’s 6:30. Time to go to the paddock.’

‘Get up?’ he groaned, ‘I’ve only just got into bed!’

I was happy enough at ‘The Dunlop’ and used to go home every weekend on my beloved Triumph Tiger 100 motor cycle. Seeing myself as next year’s Isle of Man TT winner, I used to do the 110-mile journey in two hours, which wasn’t bad going in those days of no motorways. Correct bike wear was a massive, ankle-length army despatch rider’s raincoat (featuring press studs to enclose the legs), a pair of clumpy rubber waders, sheepskin-lined, heavy leather gloves, a pair of ex-RAF Mark VII goggles and a tweed cap with the peak twisted round to the back. I was regarded as a bit of a cissy because I wore one of my father’s crash helmets, painted white. ‘If we both fall off,’ I used to say to my friends who mocked my headgear, ‘I’ll be the one who gets up.’

My mother had always hated Birmingham but I thought it was great. It was the first time I had been on my own, free from school or army discipline and completely my own master. I had a girlfriend who worked for ‘The Lucas’ and I used to go by tram from Erdington to Snow Hill to see her. The route took in Aston Cross, where there was Mitchell and Butler’s brewery, the HP sauce factory and a tannery. On a hot summer’s evening the smell was indescribable.

Nearly every morning at The Fort I had to go down the central staircase when the staff started their day’s work. On the Sections Accounts floor – about an acre of tables in rows, wall-to-wall – I would see the clerks pushing big trolleys down to the strongroom to collect their vast ledgers. When they got them back to their workstations they would spend the whole day methodically moving dockets from in-tray to out-tray, entering their contents into the ledgers. Mind-numbing work. You’d have been trampled to death if you stood in the doorway at knocking-off time. For them life began when work finished.

Frankly, my job wasn’t onerous and, like the Section Clerks, I had most of my fun outside office hours. Renewing my love of shooting, I joined the Dunlop Rifle Club to compete with my 0.22 BSA-Martini. I often visited the Birmingham Motor Cycle Club, to meet people like the famous BSA competitions boss Bert Perrigo, a chirpy Brummie, one of the all-time greats of motor-cycle trials riding; Jeff Smith and Brian Martin, trials and scramble stars of the day; and the amazing Olga Kevelos, who ran a café near Snow Hill station with her Greek father but was far more interested in being Britain’s leading female trials rider. At this time the legendary Geoff Duke, one of the greatest motor-cycle racers of all time, was making a name for himself – firstly as a works trials rider and then, in 1949, by winning the Senior Manx Grand Prix on his first appearance. We used to meet and gossip in the Norton Competitions Department in Bracebridge Street where Geoff worked – like my father so many years before.

Another of my Birmingham friends was the Ulsterman Rex McCandless, who had designed a spring frame for his grass-tracking brother, Cromie, which was blowing the socks off everything in Irish racing. Rex joined Norton as a consultant and the all-conquering Norton ‘Featherbed’ racing frame came into being. He was an excitable, fun chap but understandably used to suffer fits of depression. We’d get together in the evenings and he’d sound off at me; ‘I’ve redesigned the whole road bike range to use the Featherbed frame and now they’ve told me that they’ve got a five-year supply of frame lugs that have got to be used first,’ he once told me in despair.

If you were a motor-cycle nut in those days, as I was and still am, the Midlands was the place to be. Norton were based at Aston, BSA at Small Heath, Ariel at Selly Oak, Velocette at Hall Green, Royal Enfield at Redditch, Villiers engines at Wolverhampton and Triumph at Meriden. Now, with the glorious exception of Triumph, they are sadly all names of the past because of management complacency, union intransigence and the enterprise and competence of the Japanese.