По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

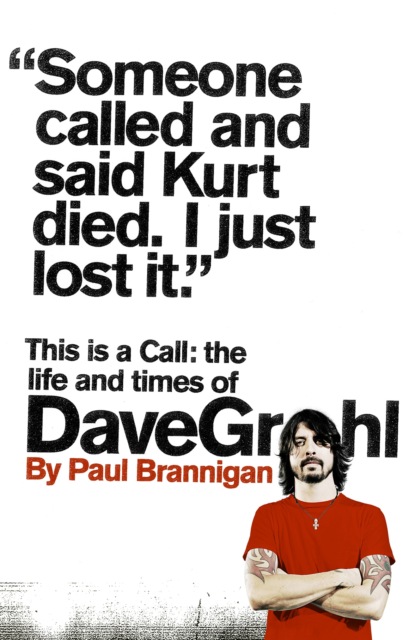

This Is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

MacKaye’s introduction to punk rock came on the night of 3 February 1979, when he attended an all-ages concert featuring New York’s trashy punkabilly ghouls The Cramps and Washington DC New Wave outfit Urban Verbs at Georgetown University’s Hall of Nations. He remembers that night as ‘one of the greatest nights of my life’.

‘At that show I entered into a whole new universe,’ he told me in 1992, as we conducted an interview in a Georgetown café three blocks from 36th and Prospect Street, the former location of the Hall of Nations. ‘I met a lot of really interesting people who challenged me artistically and emotionally and politically and sexually, people who threw up all these different ideas and alternative ways of living. And when the music you listen to challenges established notions of how music should sound, it gives you the message that rules can be broken. It was the most unbelievable, mind-blowing night.’

The Cramps’ show was a benefit gig to raise money to save WGTB, Georgetown University’s radio station, which had recently been shut down after having its broadcast licence and FM frequency sold to the University of the District of Columbia for just $1. With its provocative left-wing political bias and vocal support for gay rights, abortion rights and the anti-war movement, WGTB had long been a thorn in the side of the university’s Jesuit administration.

The majority of those in attendance at the Hall of Nations, however, were less concerned about the suppression of the station’s subversive news bulletins than by the loss of WGTB’s eclectic, playlist-free programming, which had brought punk rock to the DC airwaves for the first time. Then a 17-year-old senior at Woodrow Wilson High School, MacKaye went along to the show with friends to add his voice to the protests. Also present was his future Fugazi bandmate Guy Picciotto, then a 13-year-old student at DC’s private Georgetown Day School.

As The Cramps kicked into their ramalama rock ’n’ roll rumble, vocalist Lux Interior went into a frenzy, scaling amps, hurling microphone stands around, diving into the crowd and vomiting on the stage. Urged on by this demented master of ceremonies, the Hall of Nations’ audience responded in kind, its largely teenage occupants pinballing around the room, overturning tables and hurling chairs through windows. For Ian MacKaye, whose previous concertgoing experience was limited to arena shows by hard rock behemoths Led Zeppelin, Ted Nugent and Queen, it was an impossibly thrilling, unforgettable experience, one which instantly transformed him, in his own words, into ‘a punk rock motherfucker’.

Two weeks later, on 15 February 1979, MacKaye and his friends Jeff Nelson and Henry Garfield (now better known to the world as ex-Black Flag vocalist-turned-punk rock renaissance man Henry Rollins) went to see The Clash play DC’s Ontario Theatre on their Pearl Harbor Tour, their first US trek. London’s finest opened up with the provocative ‘I’m So Bored with the USA’ – with Joe Strummer spitting ‘Never mind the Stars and Stripes, let’s print the Watergate tapes’ – and closed with the incendiary ‘White Riot’, during which a frustrated Mick Jones repeatedly smashed his Les Paul guitar against an amplifier stack until its headstock snapped off. MacKaye, Rollins and Nelson were transfixed by the band’s fire, ferocity and fury.

‘They were detonating every song, like “use once and destroy”,’ recalled Rollins in Clash associate Don Letts’s punk rock documentary Punk: Attitude. ‘They were burning through the music like napalm. They weren’t even playing it, they were just chewing it up and eviscerating it as they went through it, like after the show there’d be no more Clash. And we walked out of there stunned. The Ramones were great, but it was like The Beach Boys compared to that … The Clash came through and just went, “Wake up, let’s go!”’

Asked in 2004 to describe Washington’s music scene at the tail end of the seventies, Ian MacKaye responded, ‘There was no music scene in Washington really, that’s my answer.’ As an erudite scholar of his hometown’s cultural history, in the late seventies MacKaye would have been keenly aware of popular local bands such The Razz, Urban Verbs and the Slickee Boys and indeed Washington’s vibrant funk-driven Go-Go scene, but those bands said little to MacKaye about his own life. The Cramps and The Clash gave him the impetus to change that.

Within weeks of attending his first punk shows, the teenager had picked up a bass guitar and formed his own punk band, The Slinkees, with Nelson on drums. The band managed to play one show in a friend’s garage before singer Mark Sullivan quit in order to attend university in New York. Undeterred, MacKaye promptly recruited a new singer, Nathan Strejcek, and changed the quartet’s name to the Teen Idles.

Another young DC band who’d fallen under The Clash’s spell were Bad Brains, four young Rastafarians from the south-east of the city. Formerly a jazz-fusion collective named Mind Power, influenced by Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, Chick Corea’s Return to Forever and John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Paul Hudson (aka H.R.), Earl Hudson, Gary Miller (aka Dr Know) and Darryl Jenifer had been introduced to punk rock by their friend Sid McCray, a fan of The Damned, the Dead Boys and the Sex Pistols. By 1979 Bad Brains were determined to outpunk everyone, mixing fat dub reggae bass lines with blur-speed rhythms, jarring tempo changes and frenetic, feral energy. At that point no band played faster, or swung harder. But Bad Brains had another mission too, to spread a doctrine of Positive Mental Attitude via vocalist H.R.’s empowering, motivational lyrics, themselves inspired by Think and Grow Rich, a self-help, personal development manual written and published by author Napoleon Hill during the Great Depression. To say that DC rock clubs, then more used to hosting coolly detached New Wave acts and rootsy rock ’n’ roll bands, were unprepared for this whirlwind of energy blowing their way is something of an understatement.

‘Bad Brains were some black youths who wanted to play punk rock and hard rock and a couple of club owners were confused and a little frightened,’ Darryl Jenifer told me in 1996. ‘Punk rock was a vulgar thing, and maybe some people wanted to look at the black situation too as a vulgar thing: one time this guy said, “We ain’t having no punk stuff in here, and damn sure we ain’t having no black punk stuff.” But we had the PMA with us at that time, Positive Metal Attitude, and the “quitters never win” concept, so these little obstacles didn’t mean that much to us.’

Inspired by stories they had heard of The Clash playing free shows in community centres in England, the quartet began setting up gigs in housing co-ops and friends’ basements, as a ‘fuck you’ gesture to the club owners who’d banned them from their premises. In doing so, the quartet helped create an alternative gig circuit in their hometown, and a template for self-sufficiency other DC bands would soon seek to emulate.

After they’d blown his band off-stage at a June 1979 show at Georgetown rock venue the Bayou, The Damned’s drummer Rat Scabies offered to help Bad Brains put together an English tour, convinced that their righteous energy would revive the UK’s flagging punk scene. That autumn, after honing their chops with a succession of shows on New York’s Lower East Side, the band decided to make the trip. They would soon discover that their PMA was no match for over-officious English bureaucracy. Arriving at London’s Gatwick airport without work visas, the quartet were detained, questioned and summarily dumped onto the next outbound flight to New York. To rub salt in the wound, all their gear was stolen.

Back in New York, the city’s punk community rallied around the band, lending them instruments and squeezing them onto bills where they could: Jimi Quidd and Leigh Sioris from The Dots even paid for a studio session for the band, during which Bad Brains recorded two songs, ‘Stay Close to Me’ and ‘Pay to Cum’. The latter, a one minute 33 seconds rush of breathless, bawling positivity, flamethrower guitar and blur-speed rhythms, would eventually become the A-side of the band’s début single, and a musical benchmark for every hardcore band that followed in their wake. But for all the support they received in NYC, just three months after departing Washington Bad Brains were back in the city, penniless and homeless. MacKaye’s Teen Idles stepped in to help, inviting their brethren to use their equipment and practice space in the basement of Nathan Strejcek’s parents’ house. Watching the older punks rehearse was an education for the kids from Wilson High.

‘Bad Brains influenced us incredibly with their speed and frenzied delivery,’ Jeff Nelson admitted in the excellent DC punk scene memoir Dance of Days. ‘We went from sounding like the Sex Pistols to playing every song as fast and as hard as we could.’

‘H.R. was the energizer,’ MacKaye stated in 2001. ‘He was really passionate about what he did. He was a visionary. He really got a lot of us kids thinking we could do anything. He was really full of great ideas and was always the one who said “Go”. They were a complete inspiration as a band.’

‘Dr Know always used to say, “Each one teach one,”’ Darryl Jenifer told me when I asked about his band’s influence on the DC scene and beyond. ‘It’s a musical tapestry we got going here. It don’t start with us. Respect is due to the magic of music, not Bad Brains.’

As the new decade dawned, stories of other bands playing urgent, raging punk rock across America were reaching DC. In the racks of Yesterday and Today records in Rockville, Maryland, an independent record store owned by former DJ Skip Groff and largely frequented by teenage punks eager to hear the latest import singles arriving from England, new releases from West Coast labels Dangerhouse, Slash, Frontier and Alternative Tentacles records were arriving weekly, bringing to the attention of Ian MacKaye and his friends bands such as The Germs, The Weirdos, Deadbeats, The Flyboys and Dead Kennedys. After graduating from Woodrow Wilson High in June 1980, MacKaye and Nelson hatched a plan to check out the nascent West Coast scene, booking shows for the Teen Idles in LA and San Francisco.

As with the Bad Brains’ proposed UK trip, things didn’t go according to plan for the adventurous young punks. In LA the quartet found themselves sharing a bill at the Hong Kong Café with obnoxious Seattle shock rockers The Mentors, Masque club regulars Vox Pop and brutal ‘biker punks’ Puke, Spit and Guts, who sang of murder and rape and looked like they would happily slit the Teen Idles’ throats for the price of a cup of coffee. More disappointingly, in San Francisco the quartet were bumped at the last minute from their promised slot on a Dead Kennedys/Circle Jerks/Flipper show at the Mabuhay Gardens by promoter Dirk Dirksen, who only reluctantly agreed to rebook them on a bill with New Wave outfits The Wrong Brothers and Lost Angeles at the venue the following evening following lobbying efforts on the band’s behalf from the Circle Jerks.

California nonetheless left indelible impressions on the young band. They took note of how punks from the Golden State – most notably the feared Huntingdon Beach crew who followed the Circle Jerks and Black Flag from show to show – conducted themselves, taking shit from no one: this was a revelation for the DC youths, who were routinely hassled and abused on the streets of Georgetown. They also noticed that the Mabuhay Gardens had instituted an ‘all-ages’ policy for gigs, marking a large black ‘X’ on the hands of audience members too young to drink alcohol to distinguish them from patrons legally allowed to purchase intoxicating liquor. On their three-day bus trip back to the East Coast the young punks talked excitedly about introducing these practices to their hometown. Washington DC was about to get a noisy wake-up call.

Back on home turf, though, cracks began to appear in the group dynamic. The experiences of the past year had left the articulate MacKaye with plenty to say, but he no longer felt comfortable putting his words into Strejcek’s mouth. The band agreed to split, but before doing so the decision was made to document their time together by releasing a seven-inch single on their own label, funded by the $600 they had amassed from their 35 live shows. The quartet had already recorded an eight-song tape with local sound engineer Don Zientara at Inner Ear Studios – a four-track tape recorder set up in Zientara’s suburban home in Arlington, Virginia – and sought advice from Skip Groff, who had his own small record label Limp Records, on the mechanics of putting out a record.

In December 1980, a month after the band played their final show at DC’s 9:30 club, the Teen Idles’ seven-inch Minor Disturbance EP emerged as the first release on the newly created Dischord record label. The cover featured a photograph of Alec MacKaye, Ian’s younger brother, with an inked ‘X’ on each of his clenched fists, an image which neatly captured the defiant mood of the emerging youth community. MacKaye and Nelson pledged that if they managed to sell enough copies of the EP to recoup some of their investment, they would use the money to put out records by their friends’ bands. It was a proud moment for the teenage punks but, never one for nostalgia, MacKaye had already moved on. By the time Skip Groff put the Minor Disturbance EP on sale at Yesterday and Today, MacKaye’s new band Minor Threat had already played their first show.

‘Revolution is not the uprising against pre-existing order, but the setting up of a new order contradictory to the traditional one.’ Printed on the inner sleeve of Fugazi’s 1990 album Repeater, this quote from Spanish liberal philosopher José Ortega y Gasset’s 1929 text La rebelión de las masas (The Revolt of the Masses) offers an insight into Ian MacKaye’s modus operandi since the night he first discovered punk rock. Raised by liberal, free-thinking, intellectual parents, for MacKaye the notion of an independent counterculture was not some intangible pipe dream, but rather a viable and attainable reality. It is this conviction that has driven his life’s work.

In October 1981 MacKaye’s first step towards independence saw him move out of his parents’ Beecher Street home in North-West Washington and take up residence in a rented four-bedroom house in Arlington with Jeff Nelson and three punk rock friends. Dischord House, as the property was known, soon became the creative and spiritual epicentre of the emerging DC hardcore community. An office for MacKaye and Nelson’s label was set up in a small room next to the kitchen, while the basement of the house was utilised as a rehearsal space for bands, among them Henry Garfield’s State of Alert (S.O.A.), Alec MacKaye’s The Untouchables, Iron Cross and MacKaye and Nelson’s new outfit Minor Threat.

When their bands weren’t practising, the young musicians spent their time at Dischord House hand-cutting and pasting record sleeves for Dischord releases (the second of which was S.O.A.’s bruising No Policy EP), designing flyers for upcoming shows, dubbing demo cassettes to trade with penpals, scribbling columns for fanzines and writing letters to record store owners, promoters and college radio DJs nationwide, anything to spread the DC punk gospel. The first Dischord releases were mailed out bearing the slogan ‘Putting D.C. on the Map’, but there was genuine pride and conviction behind the tongue-in-cheek sentiment: MacKaye regarded each release as another stepping stone towards the creation of a truly independent artistic community in his hometown. To MacKaye, Dischord was about nothing if not its sense of engagement, involvement and connection.

‘From the very beginning of the label we were told time and again that the way we were approaching the business was unrealistic, idealistic and ultimately unworkable,’ he recalled in 2004. ‘They said that it couldn’t work, and that it wouldn’t. Obviously it fucking worked.’

Dischord’s most popular, passionate and influential band was Minor Threat, arguably the defining act of the American hardcore movement. Featuring MacKaye on vocals, Jeff Nelson on drums and Georgetown Day School students Lyle Preslar and Brian Baker on guitar and bass respectively, Minor Threat played super-fast, super-tight, morally righteous punk rock that blazed with an incandescent fury which left all who saw them indelibly marked. Though Minor Threat would record just two EPs and one full-length album, their influence on the nascent hardcore movement was incalculable, their commitment to breaking down the barrier between ‘artist’ and ‘audience’ unequalled.

The band’s début release, the Minor Threat seven-inch EP was a revelation. Rather than pointing a finger at the Republican administration in the White House (as was de rigueur in hardcore circles at the time), MacKaye’s scathing, indignant lyrics targeted both his own community and everything it stood in opposition to, sparing no one, friend or foe. The EP’s most infamous song was ‘Straight Edge’, the clean-living MacKaye’s apoplectic response to substance-abusing punk rock fuck-ups who took Sid Vicious’s self-destructive cartoon nihilism as a template for their own lives.

Elsewhere he tackled themes of peer apathy, masculinity, violence and failing friendships, with equally unambiguous, thrillingly direct anger. If Black Flag’s Nervous Breakdown EP was a declaration of independence, the Minor Threat EP was a declaration of war, a war MacKaye was determined to wage all across the nation. To do so meant tapping into what author Michael Azerrad called hardcore’s ‘cultural underground railroad’, an interlinked community of promoters, fanzine writers, college radio stations, independent record stores and alternative venues.

Prior to the arrival of Black Flag there was no national grassroots touring circuit for America’s punk bands. That group’s pioneering attempts to establish a network, using phone numbers bassist Chuck Dukowski copied from the sleeves of the earliest hardcore seven-inch singles, was partly born out of necessity – by 1981 Black Flag’s hometown shows were notorious for pitched battles between punk kids and the brutal LAPD, making it increasingly difficult for the band to secure bookings anywhere – and partly derived from Greg Ginn’s desire to replicate the violent, untrammelled energy of his group’s LA shows in every town and city in the union. For Ginn and Dukowski, the idea of stepping into the unknown to confront and challenge was integral to the punk rock experience.

‘We like to play out of town,’ Ginn told Flipside in December 1980. ‘You’ve gotta threaten people sometimes.’

‘We think everybody should be subjected to us, if they like it or not,’ the guitarist added in another interview.

‘There’s more impact in playing for people who aren’t just soaking up the punk thing,’ Dukowski explained to Outcry fanzine in 1980. ‘It’s actually more stimulating to play for an audience that has not heard it and probably has a prejudice against it. You almost don’t know what to do when you’re in front of people who love it. It’s much easier when you’re in front of people who are sort of neutral or anti what you’re doing. You get all these people out there who’ve never seen it, don’t know what to expect and you get out there and blow ’em away.’

‘Greg Ginn had a ham radio thing as a teenager and through that he knew all about fucking up people from other towns – he just extended that to the idea of playing gigs,’ explains Mike Watt, now playing with The Stooges, then the bassist with Black Flag’s SST labelmates/touring partners, San Pedro agit-funk punks The Minutemen. ‘Before Black Flag there was no template. We literally had to invent this thing for ourselves. The rock ’n’ rollers really hated punk, so it was hard to play their clubs, so we’d play ethnic halls, gay discos, VFW halls, anywhere that would have us, because we also learned from Black Flag that when you ain’t playing you’re paying.’

Black Flag seemed to invite confrontation – whether this be with cops, promoters or indeed their own fans – with their every move, and each day on the road brought both fresh challenges and familiar entanglements. Henry Rollins’s Black Flag tour diaries, published in 1994 as Get in the Van, offer the most searing account of the experience of touring the USA in a hardcore band in the early 1980s, mapping out the scene’s lawless, anarchic landscape with unflinching detail. Rollins’s diary entry for 7 July 1984 was not untypical:

In the middle of the show, I took a knife off a guy and started swinging it at people in the front row. I put my other hand in front of my eyes so that they could see that I couldn’t see. I hope it bummed them out. Next, a guy handed me a syringe that looked full. He said that there was coke in it. I took it and threw it into Greg’s cabinet screen. It stuck like a dart. After the show, some fucked-up guy was trying to crawl into the van with us. I pulled out Dukowski’s .45 and put the barrel on the man’s forehead and told him to get the fuck away.

On the road Minor Threat themselves faced trouble at every turn. The didactic tone of their EP infuriated just as many punks as it inspired, with many of the group’s detractors interpreting MacKaye’s militant lyrics as a personal assault upon their lifestyle. Each night on tour MacKaye faced drunken hecklers and macho lunkheads hellbent on imparting a little attitude adjustment of their own. With tedious regularity, violence ensued.

Such hostility only added to the escalating stresses of life on the DIY circuit. Money was tight, drives were long and mind-numbing, comforts were scarce. Soon enough, the band was at war not just with the outside world, but also within: internecine arguments raged around divergent views on questions of materialism, ethics, aspirations and intentions. Yet, for all the bullshit they encountered, Minor Threat in full flight were truly transcendent, providing a visceral experience few bands of their generation could hope to match. ‘Ian MacKaye sings with more meaning and honesty than anyone I have seen,’ noted a reviewer for Flipside when the band played The Barn in Torrance, California in July 1982. ‘The crowd went nuts singing along with every song. If you miss these guys live I feel sorry for you.’

While Ian MacKaye and his friends travelled America’s highways and byways inspiring and empowering a new nationwide punk rock community, back in Washington DC Dave Grohl was embarking upon his own personal revolution.

To mark his allegiance to the punk tribe, in 1983 he gave himself his first tattoo using a needle and pen ink, a primitive technique he picked up from watching Christiane F. – Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo (We Children from Bahnhof Zoo), a 1981 film about the drugs scene in seventies Berlin. His intention was to ink Black Flag’s iconic four bars logo on his left forearm: he managed to etch three of the four bars into his flesh before the pain proved too much to handle.

Guided by Tracey Bradford’s recommendations, and the reviews of records he read in Flipside and its more politically conscious San Franciscan counterpart maximumrocknroll, he began seeking out punk rock wherever he could find it, the noisier and nastier the better.

‘Dave and I played lacrosse in junior high school and we went to a lacrosse camp at the University of Maryland the summer we were turned on to punk rock,’ remembers Larry Hinkle. ‘We both had a little spending money that week, and during a break we checked out the university’s student union book store and record store. I bought some stupid souvenir like a baseball cap or shorts or something, but Dave bought an Angry Samoans record, Back from Samoa, from the record store. It was one of his first punk records and he couldn’t wait to get home and listen to it at the end of the week. I remember asking him why he would buy a record at a lacrosse camp when he could spend his money on some cool crap like I had. I don’t remember exactly what he said, but he definitely couldn’t care less about all that stupid souvenir shit. From then on, it was all about the music.’

‘The first hardcore record I fell in love with was a maximumrocknroll compilation called Not So Quiet on the Western Front,’ Grohl recalls. ‘It was a double LP with over 40 bands from the Bay Area, so it had everyone from Flipper to Fang to M.D.C. to Pariah, and that and the Dead Kennedys’ In God We Trust and Bad Brains’ Rock for Light, those were the first three records I absolutely fell in love with. And to be honest, that’s all you need, that’s enough.

‘I was so excited by this new discovery that it became all I would listen to. I didn’t have time to listen to my old Rush and AC/DC records. I didn’t dislike them and I didn’t disown them, I was just too busy trying to find something new. It was exciting to buy albums that were a total mystery until the needle dropped. I remember buying an XTC single because I thought it would sound like GBH – I love XTC now, but goddammit at the time I was really pissed off that I’d spent those $5 on that single! But punk rock and industrial noise is a slippery slope: you start with something like The Ramones and go, Wow, now I want something faster! And then you get to D.R.I. and you go, Wow, I want something noisier! And then you get to Voivod and it’s, I want something crazier! And then you get to Psychic TV and go, I want something more insane! Pretty soon you wind up just listening to white noise and thinking it’s the greatest thing ever. But while I was listening to hardcore punk my sister Lisa was listening to Siouxsie and the Banshees and R.E.M., and we’d sometimes meet in the middle, say on Hüsker Dü. So through her I discovered Bowie and Talking Heads and stuff like that. To this day I credit her with a lot of musical influence, because had I not had an older sister like Lisa I would not have heard [Buzzcocks’] Singles Going Steady or [R.E.M.’s] Murmur or [Talking Heads’] Stop Making Sense. There was a lot of cool music in my house.’

While journeying into the dark heart of punk rock, Grohl remained preoccupied by the idea of playing guitar in a band. The circumstances which finally enabled him to do so were unorthodox. In autumn 1983 Tony Morosini, a student at Thomas Jefferson High School, spotted Grohl and Christy entertaining the elderly residents of an Alexandra nursing home, playing cover versions of Rolling Stones and Who songs on their guitars. The gig had been organised by their school’s Key Club, a civic-minded student organisation whose stated aim was to provide members with ‘opportunities to provide service, build character, and develop leadership’ by undertaking tasks to help the local community. ‘Dave and I just joined for the keg parties,’ Christy admits today.

‘So we played for a room full of people whose average age was maybe, I don’t know … 10,000?’ recalls Grohl. ‘And we played “Time Is on My Side”. Time Is on My Side? Did they enjoy it? I don’t even know if they could hear it!’

Morosini, a talented drummer, had been jamming with two fellow Thomas Jefferson High upperclassmen in the basement of his Alexandria home, and he saw the confident, charismatic Christy as the missing piece in his rock ’n’ roll jigsaw. That same week Morosini approached Christy in the school corridor and enquired as to whether the freshman student would be interested in fronting his band. Christy offered to give it a shot, but on one condition. He told Morosini, ‘It’s a package deal, though: I got Dave, and where I go Dave goes.’ Morosini shrugged his shoulders. Sure, he said, whatever, bring Dave too, we’ll be a five-piece.

The band practised regularly in the basement of Morosini’s parents’ house, hammering out covers of classic rock anthems: Bowie’s ‘Suffragette City’, The Who’s ‘My Generation’, some Stones, Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode’ and, perhaps inevitably, that evergreen punk staple ‘Louie Louie’. With a few appearances at backyard parties already under their belts, by the end of the ’83–’84 school year the band felt confident enough to put their name forward for Thomas Jefferson High School’s annual variety show competition – or rather they would have put their name forward had their band actually been in possession of a name.

‘When we registered for the show we were asked for the band name and we said “We’re nameless,”’ says Nick Christy. ‘So that’s how we got billed on this variety show, Nameless.’

The competition saw Nameless pitted against the school’s reigning variety show champions, Three for the Road, a three-piece garage band from the school’s senior year, fronted by Mississippi Senator Trent Lott’s son, Chet Lott. A degree of rivalry existed between the two bands – ‘Three for the Road always seemed like they were better than us,’ remembers Nick Christy – and the entire student body was aware that this year’s competition carried with it a new edge.