По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

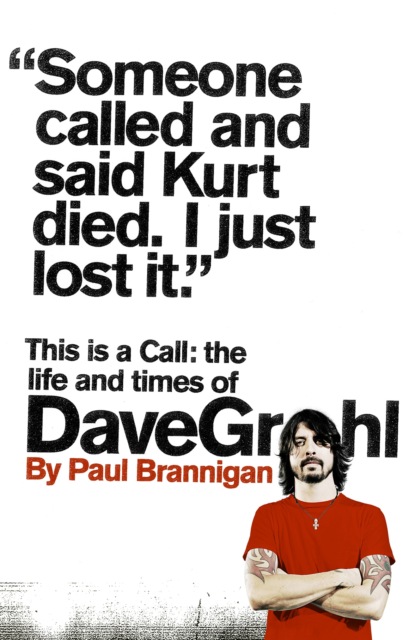

This Is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Of the songs on this second demo ‘I Can Only Try’ is a classic slice of teen angst (‘I can’t promise perfection, I can only try’), ‘Into Your Shell’ is a rallying call for noisy self-expression (‘If you’re really upset and you don’t know what to do, then shout it out or talk it out, don’t crawl into your shell’) while ‘Paradoxic Sense’, ‘Wonderful World’ and ‘Helpless’ tackle issues of growing up without giving in. The demo’s final track, ‘Now I’m Alone’, finds the singer picking over his father’s decision to leave the family home – ‘You could say that disappointment with fathers was a minor theme with MI,’ Page now wryly reflects – and celebrating the freedoms that came with his immersion in the DC punk community.

Delivering fully on the promise of their first demo, the tape showcases a committed, articulate, progressive young band gearing up for adult life with defiant self-belief: ‘Now I’m off to face a new horizon,’ Chris Page sings, ‘but I don’t think I’ll be alone.’ These words would carry an added emotional resonance in the months ahead.

In spring 1985 unmarked envelopes were pushed through the letter-boxes of a number of homes in Washington DC and suburban Virginia. Each envelope contained a photocopied leaflet, styled to resemble a kidnap ransom note, bearing messages such as ‘Wake up! This is … REVOLUTION SUMMER!’ and ‘Be on your toes. This is … REVOLUTION SUMMER’. Recipients of the letters were initially bemused, then intrigued, curious not only to discover the identity of the anonymous letter-writer and the meaning of the note, but also as to who else might have received one. A common thread quickly emerged: everyone sent a ‘Revolution Summer’ missive had been active on the DC hardcore scene at the beginning of the decade.

The letters were traced back to the office of the Neighbourhood Planning Council, a small administrative body set up by the DC Mayor’s office to host community meetings and schedule an annual free summer concert series in nearby Fort Reno Park. Located next to Woodrow Wilson High School, the office had become a de facto drop-in centre for local punks to hang out and drink sodas. While they were there they had access to Xerox machines in order to run off flyers, posters and fanzines. It subsequently emerged that the letters had been sent out by Dischord staffer Amy Pickering as a playful way to get old friends talking together once again.

The plan proved extremely effective. Pickering’s missives opened up new dialogues among the hardcore class of ’81, who began mulling over their own involvement in the punk community, debating whether it was the scene, or they themselves, that had changed with the passing years. They wondered if, and how, the idealism and integrity that had fuelled that nascent community could be rekindled. As these conversations continued, many within the group made a conscious decision to try to redefine their world. Some started new bands, others formulated new ideas and made renewed commitments to re-engaging with the social and political issues affecting their community. As Ian MacKaye explained to Suburban Voice fanzine in 1990, the phrase ‘Revolution Summer’ itself meant ‘everything and nothing’, but it was the ‘kick in the ass’ he and his friends needed.

‘We all decided that this is it, Revolution Summer,’ MacKaye told the fanzine. ‘Get a band, get active, write poetry, write books, paint, take photos, just do something.’

For Beefeater frontman Thomas Squip, another resident of Dischord House, Revolution Summer was more than just a time of musical rebirth. As he explained to Flipside in a July 1985 interview, he considered Revolution Summer to be about ‘putting the protest back in punk’. The Swiss-born singer was soon backing up his words with action. That same month he helped organise the Punk Percussion Protest, a noisy anti-apartheid rally which saw scores of young punks gather on Massachusetts Avenue to bang on drums, buckets and bins outside the South African Embassy. Soon, in close co-operation with newly formed activist group Positive Force, DC punks – including the members of Mission Impossible – were lending their voices to a wide range of causes, from protests against America’s clandestine war in Nicaragua to benefit concerns for civil liberties organisations, community clinics and homeless shelters. Chris Page remembers the time as ‘eye-opening, empowering and transformative’. With delicious irony, DC punks were taking Reagan’s ‘we must do what we know is right and do it with all our might’ words to heart, and using them in opposition to some of his most reactionary policies.

In June the new wave of DC punk was showcased by a seven-inch compilation, put together by Metrozine editor Scott Crawford in collaboration with Gray Matter man Geoff Turner’s label WGNS. Its title, Alive & Kicking, was intended as a defiant rebuttal to those hardcore zealots who considered the DC scene as dead as the American Dream. Crawford selected for inclusion Mission Impossible’s ‘I Can Only Try’, alongside tracks by Beefeater, Marginal Man, United Mutations, Gray Matter and Cereal Killer: once again, over in Berkeley, maximumrocknroll gave positive feedback.

That same month also saw the release of the first record on Dischord for two years, the first, in fact, since Minor Threat’s Salad Days single. The self-titled début album by Guy Picciotto’s Rites of Spring could hardly have been more symbolic of the scene’s regeneration.

By common consent, Rites of Spring were Revolution Summer’s most inspirational band. They sang of love, loss, wasted potential and spiritual rebirth while attacking their instruments with a commitment, intensity and kinetic fury that saw guitars and amps reduced to matchwood. Their wiry, sinewy, high-tensile compositions eschewed hardcore formulas, choosing instead to strip away the genre’s machismo in order to expose its raw, sensitive, bleeding heart. RoS shows were genuine events that saw audiences moved to tears by the group’s passionate and cathartic outpourings. They would play just fifteen shows in their short history, and Dave Grohl says that he was present at every one of them.

‘A lot of people don’t realise the importance of that band, but for us they were the most important band in the world,’ he remembers. ‘They really changed a lot in DC. They played every show like it was their last night on earth. They didn’t last long, but then for bands in Washington DC a career in music was never the intention. The motivation was “Let’s get together and fucking blow this place up, until we can’t blow it up any more.” Once the inspiration or electricity felt like it was fading, or once a band started to feel like a responsibility, they’d just break up. It was all about that moment. But those moments were so special to us.’

July 1985 also saw the return to the stage of DC hardcore’s spiritual leader. Ian MacKaye’s new band Embrace may not have been as musically adventurous as Rites of Spring, but they were a powerful, emotive unit in their own right. As with his previous band Minor Threat, Embrace asked a lot of questions, but this time MacKaye’s rage was for the most part directed inwards, as he dissected his own foibles and flaws in unflinching, forensic detail. In part, this soul-searching was sparked by MacKaye’s admiration for DC’s younger punk set. When he looked at bands such as Mission Impossible and their peers Kid$ for Ca$h and Lünchmeat, MacKaye saw a new breed of idealistic, gung-ho teen punks operating in blissful, stubborn denial of hardcore’s demise, a poignant echo of his own reaction to premature reports of the death of punk rock: it made him wonder at what point he stopped believing. ‘Those kids were super enthusiastic and it reminded us of our younger selves,’ he recalls. ‘It was inspiring to see high school kids playing again.’

‘The American hardcore movement may have been all over by 1984, but none of us wanted to believe it,’ admits Lünchmeat vocalist Bobby Sullivan. ‘It was hard for us to measure up to what had already happened, but we were all fans of Minor Threat and Bad Brains and we wanted to carry on the tradition, in the right way.’

Dave Grohl and Bobby Sullivan were regular visitors to Dischord House in the summer of ’85. Ian MacKaye had known Sullivan for years, as he was the younger brother of his former Slinkees bandmate Mark Sullivan, and he remembers Grohl as a nice kid to have around, always positive, friendly and full of enthusiasm. He first saw the pair’s bands play together at a tiny community centre in Burke, Virginia that July. For all the positive energy surrounding Revolution Summer, a number of prominent venues, including the 9:30 Club and Grohl’s beloved Wilson Center, had that summer stopped booking hardcore bills due to the attendant violence and vandalism. Lake Braddock Community Center in the new-build community of Burke had emerged as a new venue after Kid$ for Ca$h guitarist Sohrab Habibion persuaded his mother to sign up as a sponsor to allow him to use the hall for all-ages shows. In keeping with the inclusive vibe of these gigs, the new venue lacked even a stage, the division between the audience and performers having been distilled down to nothing more prohibitive than a line of duct tape marked on the ground. Mission Impossible and Lünchmeat shared this ‘stage’ for the first time on 25 July 1985; Ian MacKaye was in the audience to see them.

‘Everyone said, “You gotta see this drummer, this kid, he’s 16, he’s been playing for two months and he’s out of control,”’ MacKaye recalls. ‘And then I saw them, and Dave was just maniacal. He didn’t have all the chops down, but he was dialling it in from the gods, his drumming was so out of control, and he wanted to play so hard and so fast, it was kinda phenomenal. Everybody was like, “Woah, that guy is incredible!”’

‘One night Ian came up and told me that he thought I played just like [D.O.A./Black Flag/Circle Jerks drummer] Chuck Biscuits,’ recalls Grohl. ‘To me that was like saying, “You are just like Keith Moon,” because Chuck Biscuits was a huge inspiration to me. So from then I became that kid in town who played like that, I had this reputation as being this super-fast, fucking out-of-control hardcore drummer.’

‘Honestly, from the moment you saw Dave play, you were just in shock, because he seemed superhuman,’ laughs Sohrab Habibion, now playing guitar in the excellent Sub Pop post-hardcore band Obits. ‘I liked Mission Impossible, Chris was a really cool singer and they had great songs, but you’d see them play and there’d be this monster on the drums. Dave sat in with my band Kid$ for Ca$h for a couple of shows and it was hilarious, because the whole band was instantly transformed to a higher calibre. We played one show out at Lake Braddock with 7 Seconds and they were all just staring at him, like, “Who is this guy?”’

‘People definitely talked about him,’ agrees Kevin Fox Haley, a Woodrow Wilson High School student at the time. ‘Everyone would say, “You gotta see this kid on drums, he’s insane.” To me it seemed like it stemmed from hyperactivity, because he was kinda a spazz, and I don’t mean that in a bad way, but he was so goofy and full of energy. I’m from Washington DC and I’m sorry to say that myself, and some people from Dischord, were pretty snobby about looking down on the kids from the suburbs, so maybe at the time I was still stuck in that snobbiness where I was like, “Yeah, he’s good, but he’s from out there …” But he definitely stood out.’

For all the momentum and buzz accumulated by Mission Impossible, their days were numbered. As with so many DC bands before them, the lure of higher education was to prove irresistible. Around the time the quartet recorded their second demo tape Chris Page had been accepted to study at Williams College in Massachusetts, while Bryant Mason had been offered a place at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, meaning the break-up of the band was inevitable. Mission Impossible played its final show at Fort Reno park on 24 August alongside local art-punks Age of Consent, preceded by one last emotional show with Lünchmeat at Lake Braddock, at which the two bands decided to cement their friendship by releasing a posthumous split single. A co-release between Dischord and Sammich, a label set up by Ian MacKaye’s younger sister Amanda and her Wilson High School friends Kevin Fox Haley and Eli Janney, the EP featured three tracks taken from Mission Impossible’s April ’85 demo – ‘Helpless’, ‘Into Your Shell’ and ‘Now I’m Alone’ – alongside three Lünchmeat originals – ‘Looking Around’, ‘No Need’ and ‘Under the Glare’. As the summer drew to a close, both bands and the Sammich kids commandeered the Neighbourhood Planning Council office to cut out, fold, paste and hand-decorate sleeves for the EP. For Grohl and his friends it was a bittersweet experience. Everyone involved in the project understood that both Mission Impossible and Lünchmeat had more to offer, but the young musicians remained positive and optimistic to the end, writing slogans such as ‘Revolution Summer is for always!’ on every sleeve. As a final gesture towards the community which had nurtured, supported and empowered them both as individuals and as bands, they decided to title the EP Thanks.

‘The Do-It-Yourself element made everything more special,’ Grohl recalled in 2007. ‘When your band put the money together to go into a studio, record some songs, take the tape, send it to the plant, get a test pressing, print the labels and stuff the sleeves yourselves, the final product in your hand is just amazing. Because you know you built that shit from scratch from the ground up.’

The sun had set on Revolution Summer long before the Thanks EP received its first review. Writing in the March 1986 issue of maximumrocknroll, reviewer Martin Sprouse commented, ‘Both outfits create and exhibit three high energy melodic thrashers backed by interesting lyrics. Neither outfit falls into the DC stereotype of musical direction but really do break the ice for a lot of the underground bands from that area. Worth looking into.’ By then of course both bands were already defunct.

When all 500 copies of the Thanks EP sold out, it was re-pressed and re-released under the rather more punk rock title Getting Shit for Growing Up Different. The new title was all too apt for Dave Grohl. His relationship with his own father James hit its lowest point around the same time, when Virginia Grohl informed her ex-husband that she had found a bong belonging to their son under the driver’s seat of her Ford Fiesta prior to a morning school run. Grohl and Jimmy Swanson had discovered marijuana around the same time they fell in love with punk rock and thrash metal: they embraced the herb with equal vigour. Unbeknown to his father, by 1985 Dave was also partial to huffing lighter fluid and necking hallucinogenic drugs. During one memorable Christmas party at Kathleen Place he was tripping on mushrooms to such an obvious degree that one of Virginia Grohl’s friends steered him away from the other revellers and politely enquired if he was doing cocaine. But pot remained his drug of choice: ‘I was smoking all day long,’ he admitted in 1996. ‘I was such a burn-out. My best friend was the bong. Me and Jimmy were bonded in pot; bonded by herb.

‘The first time I took acid was in Ocean City, Maryland in 1985,’ he recalls. ‘I was forced to take it. All of my other friends had taken it. They were like, “Come on! Take it! Take it!” I said, “I don’t want to take it,” and they said, “If you don’t take it we’re just going to put it in your drink,” so I said, “Okay, I’d rather know I’ve taken it.” I liked it so much I took another about six hours in …

‘When we were teenagers, me and Jimmy were outcasts,’ he laughs. ‘We weren’t jocks, we weren’t nerds, we had created our own little world: we were all about mischief and just being petty criminals. I’m sure most people thought that we were freaks, or just uncool: we were incredibly weird and geeky but we never gave a fuck. Being “cool” in suburban Virginia was like how big of a bong hit you could take. It didn’t matter what haircut you had, or what car you had, or what pants you had on, if you could burn a whole bowl in one bong hit, you were fucking cool.’

When James Grohl looked at his son in 1985, though, he did not see Virginia’s coolest teenager. Instead he saw a smart kid whose future seemed literally to be going up in smoke. He was concerned that Dave’s teenage rebellion was rooted in deeper psychiatric problems, perhaps linked to the break-up of the family unit a decade earlier, but two sessions with a guidance counsellor failed to divine any underlying issues. In a last resort attempt to impose some much-needed discipline on the boy, it was decided that Dave should transfer from Thomas Jefferson High to Alexandria’s Bishop Ireton High School, a Catholic private school, run by priests from the Religious Congregation of the Oblates of St Francis de Sales and nuns from the Sisters of the Holy Cross, known for its strict disciplinary regime. This was not a decision likely to build any bridges between father and son.

‘I’d never cracked a Bible in my life and all of a sudden I’ve started studying the Old Testament,’ Dave complained in 2007. ‘It’s like, “Dude, all I did was take acid and spray-paint shit! Why am I here?”’

Bishop Ireton’s ecclesiastical stormtroopers faced a losing battle in trying to convert the school’s newest recruit to the gospel of Christ: by late 1985 Dave Grohl was already in thrall to new gods – British rock legends Led Zeppelin. Dave first heard hard rock’s most powerful band when ‘Stairway to Heaven’ poured out of his mother’s AM radio when he was six or seven years old – ‘Growing up in the seventies,’ Steve Albini once told me, ‘Led Zeppelin were everywhere, so saying you were a fan of Zeppelin was like saying you were a fan of air’ – but it wasn’t until the mid-eighties that the band’s majestic Sturm und Drang became an obsession for him. Every weekend Grohl and Jimmy Swanson would call around to Barrett Jones’s house in Arlington armed with a bag of weed. Together with Jones and his roommate, Age of Consent bassist Reuben Radding, the pair would get high while listening to Zeppelin’s fifth album Houses of the Holy on Jones’s new CD player. In later years, Grohl would claim to have listened so intently to the album that he could hear every squeak of drummer John Bonham’s bass drum pedal.

‘To me, Zeppelin were spiritually inspirational,’ Grohl wrote in a 2004 essay for Rolling Stone. ‘I was going to Catholic school and questioning God, but I believed in Led Zeppelin. I wasn’t really buying into this Christianity thing, but I had faith in Led Zeppelin as a spiritual entity. They showed me that human beings could channel this music somehow and that it was coming from somewhere. It wasn’t coming from a songbook. It wasn’t coming from a producer. It wasn’t coming from an instructor. It was coming from somewhere else.’

To Grohl, Zeppelin were the ultimate rock band, experimental, ambitious, mysterious, dangerous, sexual and dazzlingly adroit, capable of shifting from thunderous blues-rock riffing to gossamer-fine acoustic lullabies at a flick of Jimmy Page’s plectrum. That US music critics largely despised Zeppelin (for all their subsequent sycophantic backtracking, Rolling Stone’s review of the quartet’s self-titled début album, released on 12 January 1969, just two days before Grohl’s birth, dismissed the band’s songs as ‘weak’ and ‘unimaginative’) only enhanced their standing in Grohl’s eyes. To Grohl, guitarist Page, the conductor of Zeppelin’s light and magic, was a ‘genius possessed’ while bassist John Paul Jones was ‘a musical giant’. But it was John Bonham’s masterful drumming which truly blew his mind.

‘Led Zeppelin, and John Bonham’s drumming especially, opened up my ears,’ he told MOJO magazine in 2005. ‘I was into hardcore punk rock; reckless, powerful drumming, a beat that sounded like a shotgun firing in a cement cellar. Houses of the Holy changed everything.

‘As a 17-year-old kid raised playing punk-rock drums, I just fell in love with John Bonham’s playing – his recklessness, his precision. There were times when he sounded to me like a punk-rock drummer. [Led Zeppelin] were so out of control. They were more out of control than a Dead Kennedys record.

‘Bonham played directly from the heart. His drumming was by no means perfect, but when he hit a groove it was so deep it was like a heartbeat. He had this manic sense of cacophony, but he also had the ultimate feel. He could swing, he could get on top, or he could pull back … I learned to play by ear. I wasn’t trained and I can’t read music. What I play comes straight from the soul – and that’s what I hear in John Bonham’s drumming.’

Given his new-found obsession with Zeppelin, it was natural that Jimmy Page’s band would provide a foundation for Grohl’s next musical project. Former Minor Threat man Brian Baker had offered Grohl the chance to play with his new band Dag Nasty, but the drummer was now looking to play something more challenging than four-to-the-floor punk rock: (‘He turned me down,’ recalls Baker, ‘but you have to remember that we were children then, so it wasn’t like he turned me down flat, it was more like, “Oh, that sounds like fun, but I have to practise with these guys and … oh, hold on, Mom, I’m coming …”’) He also wanted to continue playing with bassist Dave Smith, with whom he had developed an almost telepathic understanding. The biggest problem for the pair initially was finding a guitarist who operated on the same wavelength, and could boast the musicianship to match. Both Larry Hinkle and Sohrab Habibion jammed with the pair – by now known to friends by the nicknames Grave (Grohl) and Smave (Smith) – but both guitarists readily concede now that their chops weren’t up to scratch at the time. It was Dave Smith who suggested that the duo might try hooking up with his friend Reuben Radding, as Age of Consent had just recently broken up.

The Georgetown-born son of two classical musicians – his father was a violinist in the National Symphony Orchestra, his mother an opera singer – at 18 Radding had already been a touring musician for three years. Now a well-respected jazz musician based in Brooklyn, New York, Radding – like Grohl – was a childhood Beatles fan and originally a guitarist but had switched to bass when an opportunity arose to join the Gang of Four/PiL/The Jam-influenced Age of Consent. On a personal level, Radding didn’t know Grohl particularly well – ‘To me he was this very goofy but charismatic guy who was at once both shy and extroverted,’ he recalls – but he was well aware of the teenager’s prowess as a drummer.

‘Dave’s reputation as a drummer began spreading from the first time he got behind the drums at a Mission Impossible rehearsal, well before any live gigs,’ he recalls. ‘Dave Smith had been one of my best friends for years, he lived with his parents right up the hill from me on the same tree-lined street, and one day I got a phone call, saying, “Dude, you have got to come up here and check out Dave Grohl playing drums. You won’t believe it. He’s better than Jeff Nelson!” Jeff Nelson was pretty much considered by everybody to be the best hardcore drummer around, so if Dave said that Grohl was better it was something I had to check out … it had to at least be worth a walk up the hill.

‘What I saw was exactly what had been described, and more. Grohl was flat out ridiculous. It was like watching a young Keith Moon, but he was sort of simultaneously being it and being outside it with a surprised look on his face, almost like he was watching it too and didn’t know what was making his hands and feet do these energetic and musical things. He was fun to watch right from the start. Whatever he lacked in metronomic solidity he made up for in raw excitement.

‘Mission Impossible and my band were scene friends. We loved supporting them and they were frequent followers of our shows and tapes. Stylistically we were worlds apart – I loved hardcore but I looked like a flower child or New Waver, more likely to wear paisley shirts and hand-painted sneakers than torn T-shirts and Doc Martens or Vans – but good musicians are into good music, and we shared that nonconformist, open-minded mindset of early punk rock.

‘When Mission Impossible dissolved I didn’t think that Dave and Dave’s next move would possibly involve me,’ Radding admits. ‘Even more than my lack of hardcore cred, I’d become a bass player and whatever reputation I had – not much beyond our Arlington circle, believe me – was as a bass player, an innovative one: switching back to guitar was not something I foresaw myself doing. I still owned one, though, and when Dave Smith asked if I would come do a jam session on guitar I jumped at the chance, not because I thought it was going to be a band, but because those guys were so great I wanted to experience playing with them. I dusted off my long-ignored electric guitar and got in Smave’s van for the ride down to Springfield.’

When I spoke to Radding in 2010, his memories of his first jam session with Grohl some 25 years previously were still remarkably vivid.

‘The Grohl residence was small,’ he recalled. ‘I remember Dave setting the drums up in the living room, and with Smave and I and our amps in front of them the front door to the house was only a couple feet away from my ass. They showed me the first of their “songs” – it was just a riff, really, a little guitar figure, and then the drums and bass came in in a call-and-response pattern: I don’t think I’ll ever forget what it felt like. It was not like playing music with anyone else. Listening to Dave Grohl play the drums had always been a gas, but playing with him was instantly addictive and a total rush. It was like having your ass lifted in the air as if by magic.’

Grohl’s own memories of the session were rather more prosaic: ‘We smoked a whole bunch of pot,’ he recalled, ‘wrote four songs and Dain Bramage was born.’

Led Zeppelin may have provided the common link in Radding, Smith and Grohl’s musical tastes, but their new band incorporated myriad diverse influences: Hüsker Dü, Moving Targets, Television, Mission of Burma, Black Sabbath, Neil Young and Metallica were just a handful of the bands who shaped the Dain Bramage sound. In Foo Fighters’ first press biography, released to the world’s media in 1995, Dave Grohl remembered Dain Bramage as being ‘extremely experimental, usually experimenting with classic rock clichés in a noisy, punk kind of way’. When I interviewed him for a career retrospective cover story for UK music magazine MOJO in 2009, he summed up his experiences in the band in just one sentence, stating, ‘Nobody fucking liked us, because we sounded like Foo Fighters.’

Here Grohl was being somewhat disingenuous. Ian MacKaye remembers Dain Bramage being ‘a little less euphoric than Mission Impossible, and not quite so out of control, but cool’, while some of Grohl’s closest friends, Larry Hinkle and Jimmy Swanson among them, actually rated the three piece as superior to his previous band. The band’s biggest problem was simply that they were in the wrong place at the wrong time: Dain Bramage’s Led Zeppelin-referencing, hard rock-meets-art punk sound would have made perfect sense in Washington state circa 1985 or 1986, but in the capitol of punk, the group stood out like a drum solo at a Ramones concert. Which, to a large extent, was exactly what Radding, Smith and Grohl had intended.

‘We felt like there wasn’t really a model for what we were doing,’ says Radding, ‘and it was both frustrating and a source of pride. I mean, for us it was the fulfilment of a dream to be able to present something we felt was truly our own but it could be pretty lonely at times.’

Mindful of the distance they had placed between their new band and Mission Impossible’s propulsive posi-punk, the trio approached their début gig at the Lake Braddock Community Center on 20 December 1985 with some trepidation.

‘I remember feeling really excited to share what we were working on and I knew our group was special and something different for the hardcore scene,’ says Radding, ‘but I was worried about being accepted since I’d never really been part of that scene. Everyone else seemed to know who everyone was and I had kids coming up to me asking, “Who are you?” I had long hair and was wearing a sweater over a button-down shirt and in that environment I was somewhat of an enigma.’

Dain Bramage opened up their début gig with a song called ‘In the Dark’, a reflective, mid-tempo minor key number. As he sang into a battered SM-58 mic just inches from a sea of curious faces, Radding was convinced that Burke’s young punks hated his band, but as the final notes rang out the assembled crowd broke into cheers and loud applause: ‘I was never so happy or relieved to hear a reaction like that in my life,’ he laughs.

Twenty-five years on, Radding has one other indelible memory of that first Dain Bramage performance.

‘It was the first time as a front man that I ever experienced seeing an entire audience looking over my left shoulder through the whole gig,’ he laughs. ‘I had to get used to that pretty quickly, playing with Dave. I could play all the good guitar I wanted, and sing like a motherfucker, but all eyes were gonna be on Dave all the time. At first I resented it. Then I embraced it. We should have set up like a jazz band with him on the side facing in, then at least I could have watched too. Dave’s charisma was ever-present, both in performance and off stage.

‘He was always kind of hyperactive and he bears the distinction of being the only guy I ever knew who would smoke pot and become more hyper,’ he continues. ‘When he would get stoned he would act truly deranged and go into these episodes of extroverted performance, doing skits and voices, hilarious stuff. I can still remember us laughing till we were in serious pain at some of the stuff he would do when he got stoned. It was kind of like watching Robin Williams at his best – that energy and creative spontaneity – but better than a performance because it was real.