По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

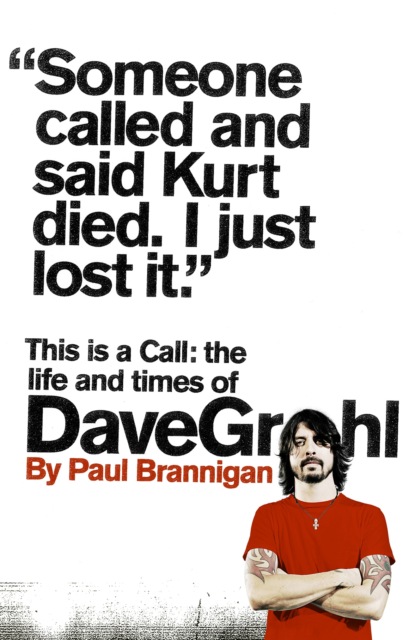

This Is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘At one point he earned a new nickname from Dave Smith. We were at some house partying and Grave had been totally going off. Next thing you know he’s passed out under a pile of clothes in the corner and someone said something like, “Well, he’s finally had it.” And Smave just shook his head. “No,” he cautioned, “he’s just energizing.” Sure enough, Dave was back up at full energy in about twenty minutes and just totally going nuts. So for a little while Dave was known as The Energizer.’

Shortly after their baptism of fire at Lake Braddock, Dain Bramage cut two demos with Barrett Jones. The first featured five tracks – ‘In the Dark’, ‘Cheyenne’, ‘Watching It Bake’, ‘Space Car’ and ‘Bend’ – while the second included a cover of Grand Funk Railroad’s 1973 Billboard chart-topping blue-collar anthem ‘We’re an American Band’, alongside originals such as ‘Home Sweet Nowhere’ and ‘Flannery’. Given Mission Impossible’s previous connection with Dischord it might have made sense for Grohl to approach Ian MacKaye about putting out a record, but the trio were (understandably) concerned that their artful post-hardcore might sound out of step with much of the didactic, righteous rage showcased on the nation’s premier punk rock imprint.

‘Looking back, we had a bunch of incorrect ideas in our heads by that time,’ Radding admits. ‘We were in a period of being down on Ian back then. We made fun of him behind his back. It’s one of the bigger sources of guilt in my recollections of that time, because the main reason we were snotty about him was just that so many people admired him so we felt like we had to tear him down. How fucking childish. I have the utmost respect for Ian and Dischord even though I like relatively little of their music. What he has built over the years is nothing short of extraordinary, and if we’d been a little less young and stupid we might have done more to join forces with Dischord or somebody else who would have carried more weight. What were we thinking?’

Unusually for a DC area band, Dain Bramage ended up signing with a Californian record label, the inelegantly named Fartblossom Records, a new venture for punk rock promoter Bob Durkee (later ‘immortalised’ in scathing, scabrous verse in the song ‘Bob Turkee’ on NOFX’s 1986 EP So What If We’re on Mystic!). Asked what Fartblossom offered that other labels could not, Radding is disarmingly honest: ‘Frankly the appeal was that he asked us,’ he concedes.

In June 1986 the band booked a four-day recording session at RK-1 Recording Studios in Crofton, Maryland with engineers E.L. Copeland and Dan Kozak (formerly the guitarist in Radding’s band Age of Consent) to record their début album. The trio had suffered a falling out with Barrett Jones – ‘They were rehearsing in our house using my PA, and there was some tension about them taking over the house and my equipment without ever really asking,’ Jones recalls – and Radding convinced his bandmates that they needed to use a ‘real’ studio in order to get a bigger and better sound for their début album. Visiting RK-1 for a reconnaissance mission, Radding was somewhat alarmed to discover that this ‘real’ studio was little more than a soundproofed suburban garage, but he swallowed his instincts and said nothing. It was a decision he would come to regret.

The recording did not go smoothly. Within minutes of the band setting up their gear on 21 June, the local police interrupted the session, having been summoned by a noise complaint from Copeland’s elderly college professor neighbour. No sooner had the cops departed than a thunderstorm knocked out all the power in the studio.

‘The power went out in the whole neighbourhood,’ Radding recalls. ‘We took a “break” that went on for hours, all of us sitting on the screened back porch watching and listening to the storm and then finally giving up and packing up a lot of our gear by flashlight. The next day’s dubbing/mixing session turned into an all-nighter. Little things seemed to take forever to accomplish.’

‘It was probably the worst first weekend of recording I’ve ever had in my life,’ Copeland, now the owner of Rock This House Audio and Mastering in Ohio, admitted to me in 2010. ‘But the band were extremely organised and we quickly caught up. There wasn’t a lot of fiddling around or double-takes, it was just boom! We blazed through the songs and it was over. All the guys in that band were really energetic, but Grohl was something special. I thought it was really weird to see somebody beat the living piss out of a drumkit, I’d never seen that kind of playing before. We had a blast, it was a good time.’

Copeland mixed the ten-track album in a day, at which point Radding sent the tape off to his label boss in Pomona. Some months later the group received in the post the test pressings of their first album, a number of songs from which the trio proudly previewed on a Sunday evening show on local ‘alternative’ radio station WHFS. Radding told the show’s presenter that the album, to be titled I Scream Not Coming Down, would be released in a matter of weeks. Back at Kathleen Place later that evening, Grohl listened back proudly to his mother’s cassette recording of the radio interview.

‘I remember thinking that it was so fucking cool that there was a DJ introducing one of our band’s songs, going out to maybe a couple of thousand people,’ he told me in 2002.

‘And that,’ he added with a laugh and a theatrically raised eyebrow, ‘was when I knew that eventually, one day, I’d become the world’s greatest rock star.’

In the weeks that followed the WHFS interview, Grohl was repeatedly stopped by friends enquiring where they could buy his album. On each occasion he promised that the album would be out in a week or two. But when weeks turned into months, with a release date seemingly as distant as the line of the horizon, such questions faded into silence. Morale in the Dain Bramage camp dipped: it was a dispiriting, frustrating time.

Late in the autumn of 1986 Dave Grohl found himself buying new drumsticks in Rolls Music in Falls Church. It was here that he spotted a note pinned among the flyers on the shop’s bulletin board. It read ‘Scream looking for drummer. Call Franz’. At first disbelieving, Grohl re-read the note several times, before tearing it from the board and stuffing it into his pocket. With Dain Bramage in limbo, he figured that he might as well take the opportunity to jam with a band he considered heroes. When he got home, he picked up the phone and dialled the number.

Gods look down

The feeling of driving across the country in a van with five other guys, stopping in every city to play, sleeping on people’s floors, watching the sun come up over the desert as I drove, it was all too much. This was definitely where I belonged.

Dave Grohl

In late 1987, as they toured America’s West Coast in support of their third album Banging the Drum, DC hardcore veterans Scream were interviewed for their first maximumrocknroll cover story. With its title inspired by Revolution Summer’s Punk Percussion Protests, Banging the Drum was Scream’s most socially conscious, politicised release to date, and writer Elizabeth Greene was keen to tease out the messages behind powerful new songs such as ‘Walking by Myself’ and ‘When I Rise’. ‘Are there any political issues that are especially important to you?’ she asked the band.

‘Apartheid,’ said singer Pete Stahl.

‘Censorship,’ said his brother Franz, Scream’s guitarist.

‘We’re kind of worried about nuclear war,’ added Pete.

Scream’s 18-year-old drummer, touring nationally with the band for the first time, chipped in with an answer of his own: ‘The drinking age,’ he replied.

Dave Grohl was just 17 years old when he joined America’s last great hardcore band. Bruce Springsteen once sang of learning ‘more from a three-minute record than we ever learned in school’: similarly, three years in Scream’s Dodge Ram van would provide Grohl with the finest education he could ever wish for. In a wonderfully evocative phrase which neatly illustrated the feral, lawless nature of the mid-eighties underground touring circuit, an ex-girlfriend once memorably claimed that Grohl was ‘raised in a van by wolves’: 25 years after joining Scream, Grohl still regards Pete and Franz Stahl as family.

Scream hailed from Bailey’s Crossroads, VA, a rural no-horse town built around the intersection of Columbia Pike and Virginia’s Route 7. The area owes its name to the fact that P.T. Barnum and James Anthony Bailey, proprietors of a circus they grandly billed as The Greatest Show on Earth, parked up their menagerie in the area in the off-season. Pete Stahl remembers his hometown as ‘very Southern, very rural and somewhat segregated … Norman Rockwellish in a way’: many of Stahl’s contemporaries on the DC punk scene simply use the epithet ‘redneck’ to describe the area and its residents.

Like Dave Grohl, the Stahl brothers had music in their bloodline: Arnold Stahl, their lawyer father, managed a popular rock ’n’ roll group called The Hangmen who were the toast of Georgetown society parties in the mid-sixties. In February 1966 the band’s ‘What a Girl Can’t Do’ single knocked The Beatles’ ‘We Can Work It Out’ from the top of the Virginia/Maryland/DC pop charts: that same month the Stahl kids got their first glimpse of rock ’n’ roll’s capacity to incite mayhem when local police were summoned to shut down The Hangmen’s in-store performance at the Giant Record Shop in Falls Church after 2,000 screaming teenagers laid siege to the store. Franz Stahl bought his first guitar from the same shop ten years later.

Scream formed in 1979, though their story truly begins in 1977, when 15-year-old Franz first started jamming on Hendrix, Skynyrd, Kiss and Funkadelic covers in local garages with two J.E.B. Stuart High School classmates, drummer Kent Stax and bassist Skeeter Thompson. Soon enough, the teenagers were turned on to garage rock and punk via two cult radio programmes, WAMU’s Rock ’n’ Roll Jukebox and Steve Lorber’s WHFS show Mystic Eyes; stomping standards by The Seeds, The Sonics and The Kingsmen were then added to their repertoire. The group were still searching for a sound and direction of their own when they first stumbled upon Washington DC’s nascent hardcore scene. Upon seeing Bad Brains lay waste to the capital’s basement dives, the scales fell from their eyes: in the rasta-punks’ searing electrical storms Scream saw rock ’n’ roll’s future. To Pete Stahl, H.R.’s crew were nothing less than ‘the greatest fucking band in the world’.

‘The first time I saw them [Bad Brains] was at a Madam’s Organ show and it scared the hell out of me!’ he told maximumrocknroll in May 1983. ‘I’d never seen a band like that. I just walked in and Doc, Darryl and Earl were just kind of back against the wall, and it was real crowded and dark, and all of a sudden H.R. just busted through the back of the crowd. It was just an intense feeling, just the tension and excitement, and as H.R. exploded through the crowd they exploded into their song! It just blew me away.’

Skeeter Thompson was equally mesmerised. Previously, the bassist had considered that he was the only black kid in the nation in thrall to punk rock: witnessing Bad Brains’ righteous ferocity at close quarters was revelatory.

‘One day Pete came over and said you’ve got to see this band,’ recalled Thompson. ‘When I first saw them it was just like, “Man, I want to do that!” So much power!’

Scream’s earliest performances took place at keg parties – or ‘beer blasts’ – in the basement of the house the Stahl brothers shared in Falls Church. Shows at Scream House, as the property was soon known locally, were spectacularly messy affairs. Starved of entertainment options in rural Virginia, every hesher, jock, pot-head and freak within a ten-mile radius would turn up on their porch on party nights. The Stahls’ basement floor would be awash with blood, sweat and beers long before the night’s ‘official’ entertainment was scheduled to begin. Inspired by Pete Stahl’s memories of his first Bad Brains show, Scream gigs always started with a violent explosion of energy: Stahl would crash through the tightly packed crowd like a raging bull, shunting beers and bodies to the four walls, and the band would kick in with concussive levels of volume. The room would duly erupt in a flurry of fists, elbows, swear words and screams. It was not uncommon for these shows to end amid squealing sirens and baton charges, as the Fairfax County police department piled in mob-handed to break up brawls.

‘It was insanity,’ laughs Franz Stahl. ‘Kids didn’t know what the hell to make of us. They were used to listening to Zeppelin or Foghat or the Allman Brothers, and what we were playing just freaked them out, it would put everybody on edge. It would get completely out of hand.’

‘Our music really pissed off a lot of the jocks and rednecks,’ agrees his elder brother. ‘It was pretty wild. At the start people either laughed at us or wanted to kill us. But soon they started to get into it, attracted by the energy of what we were doing.’

Hardcore’s bush telegraph soon carried reports of Scream’s chaotic basement parties to Dischord House. Before long, Ian MacKaye and his friends stopped by Falls Church to scope out the scene. Their presence incensed territorial local jocks, and a confrontation ensued. Recognising the DC crew as kindred spirits, the Scream team backed up their punk brethren. Predictably, fists were soon flying. When order was restored, the bloodied but unbowed Dischord and Scream House crews forged an immediate alliance, and MacKaye pledged to find his new friends slots on hardcore shows in the city. The curtain dropped on Scream House’s infamous parties soon afterwards: ‘We couldn’t afford the cleaning bills any more!’ Franz Stahl laughs.

Despite MacKaye’s endorsement, usually taken as gospel within the Dischord family, the DC punk community didn’t immediately embrace Scream. In a scene notionally populated by the marginalised and disenfranchised, they were genuine outcasts, a racially mixed, blue-collar rock band wholly uninterested in kowtowing to codified musical, philosophical or sartorial scene norms. This nonconformist mindset caused confusion and hostility: to Capitol Punishment fanzine Scream were simply ‘a bunch of jocks trying to be punk’.

The quartet’s début show in DC could hardly have been more disastrous. Booked alongside Bad Brains and Minor Threat on a fifteen-band bill at the Wilson Center on 4 April 1981, the Stahl brothers, Thompson and Stax found themselves playing to an empty room when their potential audience walked out of the room en masse as the opening chords of their set rang out. Further humiliation was to follow at a 9 May show with Minor Threat, S.O.A., Youth Brigade and D.O.A. Again, the band had barely set foot on the stage of H-B Woodlawn High School when the audience melted away. To lose one crowd may have been regarded as misfortune, to lose both was a genuine kick in the teeth for the young Virginians. But for encouraging words from scene elders Ian MacKaye and Jello Biafra (in town with D.O.A.) Scream may have abandoned punk rock at that very moment.

‘We were feeling pretty down,’ remembers Pete Stahl, ‘because we wanted to be in that scene: we identified with it and dug those bands and felt this was our natural home. So to have everyone diss us like that was pretty harsh. But Jello came up to me after we finished playing and said, “You guys are great, don’t worry about what happened.” He gave me his address and told me to send him a demo. That was a really sweet thing to do and it meant a lot.’

‘Having people turn their backs and walk out was fairly typical of the DC scene early on,’ admits Franz Stahl. ‘But them snubbing their noses at us initially just gave us that much more of a drive to smoke these guys every time we played.’

‘The first time Scream played nobody cared because they were better than all of us!’ says Brian Baker, then playing in Minor Threat. ‘They were a fantastic band, with fantastic musicians and great songs. There wasn’t really a backlash against them, but trepidation was raised from the minute they started to play. Initially people thought they weren’t cool because they had moustaches and they didn’t wear the “approved” regalia and they lived twenty miles away … and twenty miles in teenage terms is hours away. But then the moustaches disappeared, and someone bleached their hair and someone else bought a leather jacket and suddenly it was, “Hey! Now they’re one of us! Come on in!” After that they were revered by all of the Dischord people.’

In January 1983 Scream’s Still Screaming album became the first full-length release on Dischord. Produced by the band, Ian MacKaye, Eddie Janney and Don Zientara at Inner Ear, three decades on it stands up as a thrillingly urgent, impassioned and powerful collection, mixing up scratchy, Gang of Four-influenced punk-funk (‘Hygiene’), loping, spacey dub-reggae (‘Amerarockers’), Clash-style rock ’n’ roll (‘Piece of Her Time’) and thought-provoking, razor-sharp hardcore (everything else) to stunning effect. Pete Stahl lays out his band’s manifesto on the fierce ‘We’re Fed Up’, referencing his band’s past while keeping both eyes firmly fixed on the future: ‘We’re from the basement / We’re from underground / We want to break all barriers with our sound / We’re sick and tired of fucking rejection / But we’re not down ’cause we got a direction.’ It’s a ferocious statement of intent.

Given the mix of apathy and outright hostility they faced at their earliest DC shows, it was unsurprising that Scream began booking shows nationally even before the release of Still Screaming. In Putting DC on the Map (a booklet included with the 20 Years of Dischord box set) Ian MacKaye notes that Scream were the first act on his label to be paid ‘royalties’, when Dischord stepped in to help them pay for a van repair and a tour-related phone bill: this little detail speaks to the band’s proud reputation as inveterate road dogs. No DC band was more committed to taking their music to the people.

‘We didn’t really have time to think about whether anybody accepted us or not,’ says Franz Stahl, ‘we wanted to play the world and we couldn’t believe that there was this network that was already out there. DC wasn’t that big and you could only play the 9:30 Club so many times. We got out of there pretty quickly.’

The responsibility for booking Scream shows fell to Pete Stahl. He remembers his band’s earliest national tours coming together on a somewhat ad hoc basis – ‘You’d phone someone who was a friend of a friend in another town and they’d say, “Okay, this guy is going to be at this record store between twelve and two and he’ll help you put on a show”’ – but over time he built up ‘The Book’, a comprehensive database of phone numbers and addresses for record stores, promoters, venues, fanzine writers, DJs, record labels and bands in every state. For all Stahl’s meticulous planning, however, touring the nation was rarely predictable: on the road a certain ‘Wild West’ mentality prevailed. On more than one occasion the band found themselves literally staring down the barrel of a gun.

‘We had a couple of shows where we had guns pulled on us,’ recalls Franz Stahl. ‘Once in Pennsylvania we didn’t get paid and the guy pulled a gun because basically Skeeter was trying to kill him. Another time we played in New Orleans and this crazed redneck came storming into the club with a shotgun, saying, “Any y’all feel like being punk rock here?” This huge biker named Ace just stuck his hand out, whipped the shotgun out of the guy’s hand and said, “We’re not having any of that here.” That could have ended badly.’

‘You’d play a lot of crazy shows in those days,’ agrees Pete Stahl. ‘You’d have cops trying to shut down shows, there’d be tensions with skinheads – we had a black guy in the band, remember – and fights were pretty common. But we always got by.’

‘Most of the confrontations we had were with drunks, people who just happened to come to the club for a drink and got stuck with us,’ says Franz. ‘But Skeeter was a big, cut dude and my brother was afraid of no one, so they’d shut down situations pretty quick. Pete was never scared to jump in the middle of potential fights. People would just back away saying, “These motherfuckers are crazy.”’

Following the example set by Minor Threat and Faith, in spring 1983 Scream decided to flesh out their sound with the addition of a second guitar player. Their new recruit could hardly have been more at odds with the DC punk aesthetic. Robert Lee Davidson – better known by his nickname ‘Harley’ – played in a Judas Priest-influenced metal band called Tyrant, and first met the Stahl brothers while dating their sister Sabrina. Every bit as stubbornly independent as his new bandmates, the candy-floss-haired, studs-and-leather-wearing metal-head made absolutely no attempt to tone down his look to assimilate into the DC scene, horrifying elitist punk purists. This secretly gave Pete and Franz Stahl no small amount of pleasure.

Whatever his perceived sartorial shortcomings, Davidson was an undeniably gifted guitarist, and his fluid, technical hard-rock style helped Scream tap deeper into primal rock ’n’ roll sources on their superb second album, 1985’s This Side Up. The new guitarist’s metallic influences are most evident on ‘Iron Curtain’, a not-entirely-convincing Aerosmith-meets-Judas Priest headbanger replete with squealing guitar leads, but elsewhere This Side Up swaggers and slams with a confidence and agility of which Bad Brains themselves would have been proud.

The rollicking ‘Bet You Never Thought’ could have fitted seamlessly onto The Clash’s London Calling; the title track is an exhilarating tangle of Buzzcocks guitar and air-punching PMA (‘Yesterday it rained so hard I thought the roof was gonna give / But now today’s so bright, just wanna let it all in’) while the soulful ‘Still Screaming’ matches shimmering minor key reggae with skronking jazz saxophone. Elsewhere, ‘I Look When You Walk’ has a sexy garage rock groove, and album-closer ‘Walking Song Dub’ mixes arty, experimental found-sound collages with booming dub basslines, cut-and-paste vocal loops and a whistled melody line. Within a scene hovering dangerously close to self-parody in the mid-eighties, This Side Up was a genuine revelation. In 1997 Dave Grohl nominated it as one of the most significant albums of his adolescence.

‘This is the album where Scream went from being a hardcore band into being a rock band,’ he told England’s now defunct Melody Maker magazine. ‘They sounded like Aerosmith and I loved that. I liked the fact that they had long hair, that they weren’t straight edge and that they played this kinda hard-rock/hardcore thing. It made me realise there was a place for me making music.’

With a superb new album to draw upon, and with their sound bolstered by Davidson’s muscular fretwork, Scream quickly acquired a reputation as one of the punk scene’s unmissable live draws. When the quintet came through Boston in April 1985, Suburban Voice editor Al Quint declared their set at the Paradise ‘the best set of the year, so far’.

‘The perfect combination of speed, power and melody,’ Quint wrote. ‘The new songs combine those attributes and more. Pete Stahl has charismatic stage presence, able to draw people together, while the band’s versatile, uptempo sound, spearheaded by a two-guitar blitz, keeps on coming. The band’s newer material has been lumped into the metal classification, but it’s coming more from a late sixties hard-rock style – bands like Ten Years After, Steppenwolf (especially their 10-minute jam of “Magic Carpet Ride”) or Blue Cheer have influenced their newer material. Scream are definitely in the top echelon of American bands.’