По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

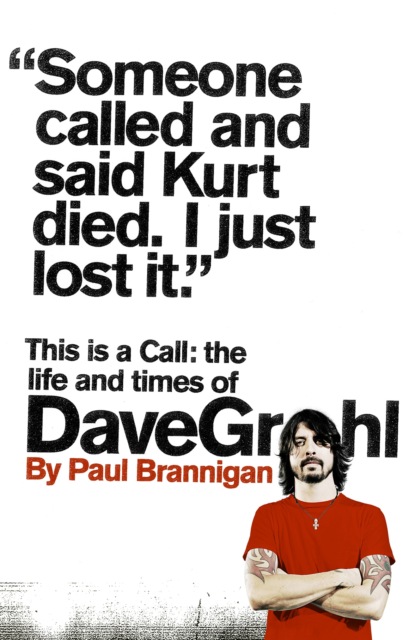

This Is a Call: The Life and Times of Dave Grohl

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘We had won this contest every year so we just assumed we were going to win it forever,’ recalls Chet Lott, now a 44-year-old political lobbyist working alongside his father and former Louisiana Senator John Breaux at the Breaux Lott Leadership Group in Washington DC. ‘Maybe we were a little naïve. When they showed up it was like, “Oh, hell, now we got some real competition here!”’

On the day of the competition Nameless played well, blasting through raucous covers of The Who’s ‘Squeezebox’, Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode’ and their trump card, Kenny Loggins’s recent Billboard chart-topper ‘Footloose’. Three for the Road followed with a strong set of their own, turning in powerful versions of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Honky Tonk Women’, The Who’s ‘Can’t Explain’ and Creedence Clearwater Revival’s ‘Have You Ever Seen the Rain?’ The fate of both bands lay in the hands of their audience, quite literally, as the contest was to be decided by the volume of applause garnered by each act. Ultimately, to Grohl’s intense disappointment, Three for the Road triumphed once more. ‘All the chicks loved them,’ a rueful Grohl admitted 25 years on.

‘Those guys had some real chemistry in their band, and obviously some great musicians,’ recalls Chet Lott, an accomplished musician himself, with two albums of soulful, country rock to his name. ‘In Three for the Road we were not great musicians individually, but as a unit we were pretty good. And because we’d been around since freshman year that helped us a little bit in the talent show as we already had a bit of a following. I don’t think Dave Grohl has lost out too often since that day …’

The June 1984 Thomas Jefferson High School variety concert was to be one of the Nameless’s final appearances. Just a few months later, following his parents’ divorce, Nick Christy’s mother moved her family back to Massachusetts; without their frontman the band soon petered out. Amusingly, in 2009, when I asked Grohl about the band’s demise, he put his own tongue-in-cheek, mythologising spin on the breakup: ‘We lost a couple of members to drugs, women and fast cars,’ he said with a shrug. ‘Hey, it was North Virginia, it was crazy …’

By 1984 the American hardcore scene itself was slowly disintegrating. Many of the musicians who had helped build the community no longer recognised or respected it. Violence and drug abuse prevailed, younger acts seemed content to ape their heroes rather than search for their own voice, and arguments about politics, sexism, racism and ethics played out in the letters pages of fanzines. The civil war tearing the scene apart was one of the topics under debate when maximumrocknroll brought together Ian MacKaye, Articles of Faith’s Vic Bondi and M.D.C.’s Dave Dictor for a round-table discussion in the summer of 1983. MacKaye’s exasperation was all too evident when at one point he asserted, ‘Punk rock has more assholes, in a ratio sense, than any other kind of music. They don’t have respect for anything, it drives me crazy.’ Something had to give. And in September 1983, as the issue went on sale, his band Minor Threat played their final show.

In truth, the members of this volatile and relatively short-lived group were never the best of best friends, and would argue constantly – about songwriting, about MacKaye’s lyrics, about their relationship with Dischord and their future plans. ‘I have some really great practice tapes with about seven minutes of music and about eighty-three minutes of arguing,’ MacKaye would wryly note years later.

By the time the quartet recorded their début album Out of Step with Don Zientara in January 1983, MacKaye was already directing much of the anger in songs such as ‘Betray’, ‘Look Back and Laugh’ and ‘Cashing In’ squarely at Preslar, Baker and Nelson. Minor Threat may have been out of step with the world, but they were also increasingly out of step with one another, and their status as kingpins of the national hardcore scene only exacerbated divisions within a band that bassist Baker once scathingly dismissed as ‘an after-school hobby for some over-privileged kids’.

‘Part of the split was that Lyle and I – what a surprise, the private school kids – wanted to continue to build and to see where this could go,’ Baker told me in 2010. ‘I mean Minor Threat never left the United States and we wanted to see the rest of the world: we thought that there was potential to keep moving forward. And that really wasn’t in the cards and so basically that’s what split us up. Aspirations tend to ruin the best of intentions.’

On 23 September 1983 Minor Threat played their final show, opening up for DC Go-Go legends Trouble Funk at the Landsburgh Center. They aired a new song for the first, and last, time.

‘Salad Days’ was MacKaye’s unflinching dismissal of a scene he felt had become stagnant and compromised, driven by sounds of fury which came increasingly to signify nothing. The song’s bitter lyrics were all the more powerful coming from a man whose belief in the power of music and art to empower, engage and inspire had been so well documented.

The mood of the song struck a resounding chord with many in the punk community. In spring 1984 maximumrocknroll placed the bald question ‘DOES PUNK SUCK???’ on its front cover. That same spring, 12-year-old Scott Crawford interviewed Ian MacKaye for the first issue of a new DC scene fanzine called Metrozine. Though more than six months had passed since Minor Threat’s final show, the young writer found MacKaye unwilling or unable to drag himself out of his slough of despond.

‘He was so down, so totally over the whole scene,’ says Crawford, now the editor of Blurt magazine. ‘There was no suggestion of him forming another band, he was so disillusioned and disenchanted. It was actually pretty painful to see.’

Interviewed by Flipside around the same time, Black Market Baby frontman Boyd Farrell offered another doomy insider’s prognosis of the DC scene.

‘It’s sad, all those little kids that were on skateboards a year or two ago are on heroin now,’ Farrell commented. ‘It’s like DC lost its innocence. It’s been deteriorating since the end of Minor Threat, though obviously it isn’t their fault. It’s like a fashion thing now. It’s like it lost the sincerity, the anger, and became more cynical. You used to be able to go to the clubs and get a buzz from the bands’ energy.’

One year on, in April 1985, Skip Groff filed Minor Threat’s final single alongside the Teen Idles’ Minor Disturbance EP, State of Alert’s No Policy EP, Government Issue’s Legless Bull EP and Youth Brigade’s Possible EP in the Dischord rack at Yesterday and Today. Recorded on 14 December 1983, almost two months after the band had played their final show, Salad Days felt like the requiem for a shared dream. Yet, typical of the DC punk scene’s capacity for death and renewal, in the same month that the single went on sale another young area band were entering a recording studio to record their début EP. This would be the first seven-inch single to bear Dave Grohl’s name.

Chaotic hardcore underage delinquents

For bands in Washington DC a career in music was never the intention. The motivation was, ‘Let’s get together and fucking blow this place up …’

Dave Grohl

On the afternoon of 21 January 1985 Ronald Reagan stood in the magnificent Capitol Rotunda for the swearing-in ceremony that would begin his second term as President of the United States of America. Re-elected following a landslide victory over Democratic Party candidate Walter Mondale, Reagan promised a new dawn for a nation emerging from the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

‘My fellow citizens, our nation is poised for greatness,’ he told the American people in his second inaugural address. ‘We must do what we know is right and do it with all our might. Let history say of us, “These were golden years …”’

In the same month that President Reagan was filling a cold January day with hot air, across the Potomac River, in Arlington, Virginia, a new band was formed. For vocalist Chris Page, guitarist Bryant ‘Ralph’ Mason, bassist Dave Smith and 16-year-old drummer Dave Grohl, Mission Impossible represented their own new beginning, as all four band members had previously played together in Freak Baby, one of the new acts who had emerged on the DC scene in mid ’84, around the time maxiumumrocknroll published its contentious ‘Does Punk Suck?’ issue. Freak Baby were by no means the best of DC punk’s second-wave bands – indeed Dave Grohl fondly remembers them as being ‘awful’. But the quartet were possessed of a boundless energy and a knack for short sharp shock pit anthems, the best of which (‘Love in the Back of My Mind’, ‘20–20 Hindsight’ and ‘No Words’) rang out like Stiff Little Fingers played at 78 rpm. In 17-year-old skatekid vocalist Page, Mission Impossible also had a frontman with genuine charisma and presence.

Now a married father of two working on environmental education projects in his native Seattle, Chris Page discovered punk rock in 1983, when he heard his Yorktown High School classmate Brian Samuels blasting Bad Brains’ self-titled ROIR cassette on a boombox in the school playground: ‘As with Dave, my dad left the family, and I was angry and confused at the time,’ he recalls. ‘And this was like nothing I’d ever heard before. I thought it was amazing, just incredible. That and the first Minor Threat record were my introduction to this world.’

Samuels helped Page navigate his way into Washington DC’s underground punk network: on weekends the pair would ride the DC Metro’s Orange and Blue lines from Rosslyn into the city to check out the scene. Page recalls his initial journeys into the heart of DC being ‘an adventure’ – ‘There’s all kinds of dark stuff in the city that you don’t see in the suburbs,’ he notes – and the shows being characterised by ‘pure, explosive, sweaty energy’.

‘There was definitely something special happening in DC at that time,’ agrees Hollywood film star and 30 Seconds to Mars frontman Jared Leto, who lived in the city from 1983 to 1984. ‘That scene was really vibrant, and the characters in it were such individuals. I worked in a nightclub right across the street from the 9:30 so I could walk in there every night and we saw some crazy shit. The shows were just free-for-all madness, with the singers jumping off the stage into the audience and passing the mic around. It was definitely a fun time.’

For Dave Grohl, the 1983 Rock Against Reagan show helped shine a light on this underground community. That July day was the first time he saw flyers advertising all-ages punk shows, hosted in off-the-beaten-track venues never listed in the Washington Post’s Arts section or DC’s newly established free listings paper the City Paper – hole-in-the-wall city centre clubs like dc space and Space II Arcade, suburban community centres such as the Wilson Center and hardcore gig-friendly restaurants such as Food for Thought in Dupont Circle. Emboldened by memories of his night at the Cubby Bear, he stage-dived headlong into the scene.

‘No one was sniping my neighbourhood with Black Flag flyers on the weekend,’ he remembers, ‘so initially that scene stayed pretty underground. But as soon as I found out about these shows I was like, “Man, if I could just get a ride …” All day long I’d mow lawns to make enough money to go into the city at the weekend: I’d have my Walkman on, blasting out Dead Kennedys In God We Trust and Bad Brains Rock for Light and Minor Threat’s Out of Step and the Faith/Void album and I’d be wondering what the weekend would have in store.

‘I’d get dropped off or take the Metro down to the shows in inner city DC on my own, and initially I didn’t know anyone. At that time in Washington DC there were three or four people getting killed every night over drugs: there was crack cocaine and a new drug called Love Boat – nobody knew what the fuck it was, it could have been embalming fluid, but you smoked it and it would burn white hot like an electrical fire and make you feel like you were sitting in your own blood for about four hours. It would make people kill each other. It was fucking crazy. So here I was, a 14-year-old kid on my own, on a Friday night in the murder capital of the world …

‘But then you’d go into these shows, and they’d be amazing. There was always the sense that anything could happen. There were people selling fanzines and people giving out stickers, and there’d be broken glass and fights and every once in a while someone would get stabbed. The venues were shitty, the PAs never worked and there were always technical difficulties, but you didn’t judge a band on performance as much as you judged them on audience participation. And your new favourite band could sound completely different than they did on the single you’d bought last week.

‘Trading tapes and buying singles and ordering fanzines by mail, all of those things became so special to you. You’d get a single by a band from Sweden in your mailbox and then a year later they were playing the shithole down the street? You can imagine the feeling: you’d walk in and see them in person and then they’d plug in and play the songs that you loved from that single that you ordered for two dollars a year ago and it meant the world to you, it was fucking huge. So that spirit, I consider it now to be just the spirit of rock ’n’ roll, that spirit of music meant more to me than anything else.’

On his trips into the city, two local bands in particular stole Grohl’s heart: Bad Brains and Virginian hardcore heroes Scream.

‘The first time I saw Scream was at one of those Rock Against Reagan shows,’ he recalls. ‘Scream was legendary in DC. They were from my neighbourhood, from Bailey’s Crossroads in suburban Virginia, which was maybe ten miles away from North Springfield, and if ever the DC scene seemed elitist or insular or hard to crack it didn’t matter, because Scream were from my fucking neighbourhood! We were so proud of that because not only were they one of the best American hardcore bands, but they were the best in DC: Bad Brains had moved to New York, Minor Threat were gone and Rites of Spring were amazing, but they weren’t playing hardcore. And Scream played everything. You would go to see them and they would play the first three songs off [their 1983 début album] Still Screaming, which are unbelievably bad-ass hardcore songs, and then bust into [Steppenwolf’s] “Magic Carpet Ride” and then do some weird space-dub shit for a couple of minutes and then pile back into something that sounded like Motörhead. They were so fucking good. They didn’t give a fuck what anyone thought of them, they didn’t give a shit. They were the under-dogs because they were from Virginia. And we looked up to them so much.

‘But nobody else blew me away as much as Bad Brains,’ Grohl admitted in 2010. ‘I’ll say it now, I have never ever, ever, ever, ever seen a band do anything even close to what Bad Brains used to do live. Seeing them live was, without a doubt, always one of the most intense, powerful experiences you could ever have. They were just … Oh God, words fail me … incredible. They were connected in a way I’d never seen before. They made me absolutely determined to become a musician, they basically changed my life, and changed the lives of everyone who saw them.

‘It was a time when hardcore bands were these skinny white guys, with shaved heads, who didn’t drink and didn’t smoke and made fast, stiff and rigid breakbeat noise. But the Bad Brains when they came out, it was like if James Brown was to play hardcore or punk rock! It was so smooth and so fucking powerful – they were gods, man, they were way more than human. To see that kind of energy and hear that kind of power just from a guitar, bass, some drums and a singer was unbelievable. It was something more than music and those four people onstage. It was just fucking unreal.

‘The DC scene wasn’t a huge scene,’ Grohl remembers. ‘If a local band like Scream or Black Market Baby or Void played you’d probably have maybe 200 people show up, the same 200 people every time: if you had a band like Black Flag play, then there’d maybe be 500 or 600 people there. We called those extra people the “Quincy Punks”, people who had seen one punk rock episode of [popular NBC crime drama] Quincy and then heard that Black Flag was coming to town. Those were usually the shows that had the most trouble. But the other gigs would have just a few people so you just started seeing the same people around. I’d be starstruck and intimidated when I would see, like, Mike Hampton from Faith or Guy [Picciotto], because these people were my musical heroes and I knew every word to every one of their songs, but you’d be singing along with a band and ten minutes later they’d be diving on top of your head when the next band was on. There was no separation between “bands” and “fans”, and that was my idea of some sort of community.

‘For me, punk rock was an escape, and it was rebellion. It was this fantasy land that you could visit every Friday evening at eight o’clock and beat each other to bits in front of the stage and then go home.’

It was at a Wilson Center show by Void, a chaotic, impossibly intense punk-metal quartet from Columbia, Maryland, that Grohl first met Brian Samuels in autumn 1984. At the time Samuels’s band Freak Baby were seeking to add a second guitar player to their line-up, just as scene elders Minor Threat, Faith and Scream had done the previous year, and Samuels invited the young guitarist to an audition at the group’s practice spot in drummer Dave Smith’s basement. Grohl wasn’t the best guitar player the band had ever seen – Chris Page remembers him as being merely ‘competent’ – but what he lacked in technical dexterity he made up for in terms of the energy, enthusiasm and infectious humour he brought to the band. In addition, Grohl’s simple but effective rhythm playing neatly complemented Bryant Mason’s more proficient lead guitar work. Freak Baby’s newest member made his début with the band that winter, playing as support to Trouble Funk at Arlington’s liberal-minded, ‘alternative’ high school H-B Woodlawn. It would prove to be the band’s one and only show as a quintet.

Freak Baby’s demise was sudden and brutal. One afternoon in late 1984 Grohl was behind Dave Smith’s kit at practice, trying out some of the rolls, fills, ruffs and flams he had been practising for years in his bedroom of his family home in Springfield. He had his head down, and eyes closed: his arms and legs became a blur as he hammered out beats to the Minor Threat and Bad Brains riffs running through his head. Lost in music, Grohl was oblivious to his bandmates urging him to get back to his guitar. Standing six foot five inches tall, and weighing in at around 270 pounds, skinhead Samuels was not a figure used to being ignored. Grohl didn’t notice his hulking bandmate rise from the sofa, so when Samuels yanked him off the drum stool by his hair and dragged him to the ground, he was more shocked than hurt. The rest of his band, however, were mortified. They had felt that Samuels had been increasingly trying to assert his authority and control over the band, but this was too much. As Grohl stumbled back to his feet, Chris Page called time on the day’s session. Within the week he would call time on Freak Baby too, reshuffling the line-up to move Grohl to drums, Smith to bass, and Samuels out the door. With the new line-up came a new name: Mission Impossible.

With the domineering Samuels out of the picture, initial Mission Impossible rehearsal sessions were playful, productive and wildly energetic: all four band members skated, and at times Smith’s basement resembled a skate park more than a rehearsal room, with the teenagers bouncing off the walls and spinning and tumbling over amps and furniture as they played. But there was also an intensity and focus to their rehearsals. Songs flowed freely as they bounced around ideas, fed off the energy in the room and experimented with structure, tone, pacing and dynamics. Just two months after forming, the band felt confident enough to record a demo tape with local sound engineer and musician Barrett Jones, who had helmed a previous session for Freak Baby. Jones fronted a college rock band called 11th Hour, North Virginia’s home-grown answer to R.E.M., and operated a tiny recording studio called Laundry Room, so called because his Tascam four-track tape deck and twelve-channel Peavey mixing board were located in the laundry room of his parents’ Arlington home. Now running a rather more sophisticated and expansive version of Laundry Room Studios out of South Park, Seattle, Jones has fond memories of the session.

‘I’d recorded a tape for Freak Baby with Dave on guitar, but when he switched to drums their band was just so much better,’ he recalls. ‘They went from doing one-minute hardcore songs to doing … two-minute hardcore songs! But those songs were more ambitious and involved and dynamic.

‘Back then Dave was probably the most hyper person I’d ever met,’ he adds. ‘When we did that first Freak Baby demo he was literally bouncing off the walls. They were a hardcore band, so they all had that energy, but he was something else. But musically his decision to switch to drums was definitely the right one.’

‘Once Dave got behind the drums he was very obviously something special,’ says Chris Page. ‘He was doing stuff that nobody else was doing, incorporating little riffs and ideas that he’d pinched from some of the great rock drummers he listened to. He took great pride in us being the fastest band in the DC area, but there was so much more to his playing than just speed and power. And that started to affect our songwriting, because even though our songs were maybe only one minute or a minute and a half long we wanted to showcase his talent and build in space for those parts.’

The first Mission Impossible demo neatly captured the quartet’s combustible energy. It provides a snapshot of a band in transition, mixing up vestigial Freak Baby tracks and goofy cover versions (most notably a take on Lalo Scifirin’s theme for the Mission Impossible TV series, with which the band opened every gig) with more nuanced shards of hardcore rage. Across twenty tracks the shifts in tone occasionally grate – the decision to include a screeching romp through a BandAids advertising jingle alongside a thoughtful, articulate song such as ‘Neglect’, in which Page delivers a spoken-word lyric juxtaposing the privileged consumer lifestyles of the suburbs with the poverty and pain he encountered on visits to inner-city DC, rather betrays the quartet’s youthful over-exuberance – but at their best Mission Impossible were a genuinely thrilling prospect.

Among the more light-hearted selections on the tape, two tracks stand out: ‘Butch Thrasher’ is Grohl’s mocking paean to the macho knuckledraggers who considered punk rock moshpits their private battlefields, while ‘Chud’, inspired by the kitschy 1984 horror movie C.H.U.D., sees Page screaming ‘Chaotic Hardcore Underage Delinquents! Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers!’ while trying to keep a straight face. Of the more sober tracks, ‘Different’ deals with the hassles devotees of punk rock faced from parents and peers unsympathetic to the lifestyle, while ‘Life Already Drawn’ echoes the sentiments Ian MacKaye expressed in the song ‘Minor Threat’ with Page screaming ‘Slow down!’ at teen peers who seemed in an unseemly haste to join the adult rat-race.

Two Dave Grohl-penned originals also warrant mention: ‘New Ideas’ stands as the fastest song in MI’s repertoire, packing whammy bar divebombs, squealing harmonics, two verses, three choruses and a jittery, atonal Bryant Mason solo into just 74 seconds. Elsewhere ‘To Err Is Human’ was arguably the demo’s most sophisticated track, its driving rhythms and sudden dynamic shifts in tempo and key bearing the influence of Grohl’s favourite new band, SST’s Hüsker Dü, the brilliant Minneapolis trio whose stunning 1984 double album Zen Arcade had rendered hardcore’s perceived boundaries obsolete, and drawn favourable comparisons to The Clash’s London Calling album in mainstream music publications. ‘To Err …’ was significant not only for highlighting the increased maturity of Grohl’s songwriting, but also for flagging up to his new friends issues in his personal life, specifically in regard to his relationship with his father.

Over the years Dave Grohl has stubbornly resisted journalists’ attempts to play amateur psychologist over the impact his parents’ divorce had upon his life. It would make for a convenient narrative if his drive, energy, work ethic and subsequent success could be linked back to a teenage desire, conscious or subconscious, to scream ‘Look at me now!’ at the man who walked out on his family; if his entire artistic raison d’être could be traced back to the rejection, resentment, anger and pain he felt as the child of a broken home. But time and again Grohl has rejected this analysis. ‘There was some Nirvana book that glorified my parents’ divorce as if it were my inspiration to play music,’ he protested in 2005. ‘Completely untrue. The fucking Beatles were the inspiration for me to play music.’

Nevertheless, Dave had James Grohl in mind when in spring 1985 he scribbled the lyrics to ‘To Err Is Human’ in his notebook: ‘To err is human,’ he wrote, ‘so what the fuck are you? Working so hard to make me perfect too …’

At the time, Grohl’s visits to see his estranged father in Ohio were regularly punctuated by finger-pointing lectures, explosive arguments and sullen, protracted silences. As a speechwriter for the Republican Party, James Grohl was a master of the dark art of transforming trenchant opinions on morality, ethics and law and order into screeds of fiery rhetoric, and he was never shy of sharing his views with his teenage son, regardless of whether Dave wanted to hear them or not: ‘Imagine the lectures I’d get if I fucked up,’ Grohl commented in 2002. ‘I’d get the State of the Union address!’

With his grounding in classical music, James had firm views too on the self-discipline required of performing musicians – ‘He thought that unless you practised for six hours a day you couldn’t call yourself a musician,’ his son once noted – and Dave’s basement thrashings didn’t exactly match up to his lofty ideals. Even after Nirvana’s Nevermind album became a worldwide phenomenon, Dave Grohl was still mindful of his father’s occasionally dismissive attitude to his career. ‘Dave and I were at his house one night,’ his friend Jenny Toomey told me during the research for this book, ‘and I remember him talking about his father being critical of him for not being a “real” musician and I thought that was really sad,’ so one can only imagine the snarky, offhand comments that would have been directed towards him during his formative years in the DC punk underground.

During these difficult times music provided Dave with both a pressure valve and an escape hatch. His spirits were buoyed as Mission Impossible’s demo quickly built up a word-of-mouth buzz on the tape-trading underground, attracting plaudits both nationally and overseas. The band were name checked by maximumrocknroll editor Tim Yohannon in a review of Metrozine’s DC area cassette compilation Can It Be? (which featured MI’s ‘New Ideas’), and secured their first international release around the same time when French punk rock label 77KK included ‘Life Already Drawn’ alongside tracks by D.O.A., California’s Youth Brigade, Red Tide and the best up-and-coming French punk acts on their début release, a compilation album also titled 77KK.

In April 1985 Mission Impossible returned to Laundry Room Studios to cut a second demo. The quartet were now writing collaboratively, pushing one another to create more complex, challenging material, and a new-found self-assurance shone through in each of the six new tracks demoed with Barrett Jones. Hardcore’s ‘loud fast rules!’ ethic still provided a foundation for the new material, but MI had learnt that silence and space could be harnessed to accentuate volume and weight as readily as thrashing powerchords. Chris Page was growing in confidence as a lyric-writer too, and the conviction with which he delivered each word rendered his tales of teenage travails wholly believable.