По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

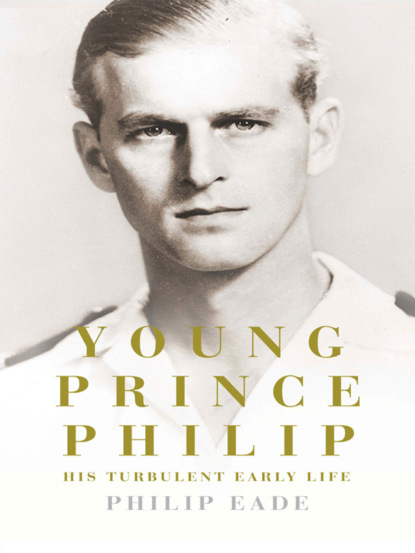

Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

he, too, was to join the Nazi party, in 1937, along with Cecile.

Alice felt understandably wretched at being excluded from all the celebrations and when she received flowers from her daughters as a token of their engagements she spent much of the day crying. Five days after Philip’s birthday, Cecile wrote to her from a ‘terribly hot’ Wolfsgarten, reporting that they had been bathing ‘everyday at least twice including Philipp [she used the German spelling of his name]’. Andrea had arrived looking ‘rather tired’ and in due course had left for Marienbad, the spa town in Bohemia, ‘already much fatter and browner’. Philip was

quite blissful … U Ernie and A Onor gave him a new bicycle for his birthday and he rushes about on it all day. In the evening from the moment he has finished his bath till he goes to bed he plays his beloved gramophone which you gave him. He got really lovely presents this year. Dolla and Tiny gave him pen-knives, and Don a big coloured ball for the swimming pool, and I gave him a rug to lie about on in the garden. He is very good and does just what A. Onor tells him.

In another letter, Cecile described how ‘Philipp appeared in his uniform and looked adorable, everybody was delighted, especially A Sophie who worships him’.

Alice was especially grateful to Cecile for describing her son’s birthday, ‘particularly thoughtful of you … as no one else has done so’,

and she remained eager for news of him, urging him the next month to ‘write me a postcard and tell me what you are doing’.

Around the same time Philip’s former nanny, Nana Bell, herself wrote to Philip: ‘I know how difficult it is to write letters on holiday [but] you must write to your dear Mama often.’

Philip was taken to see his mother a handful of times over the next two years, and otherwise received only occasional letters and cards from her. For the five years after that, from the summer of 1932 until the spring of 1937, he neither saw nor heard from her at all. He was subsequently at pains not to overstate the effect of all this. ‘It’s simply what happened,’ he told one biographer. ‘The family broke up. My mother was ill, my sisters were married, my father was in the South of France. I just had to get on with it. You do. One does.’

Yet while he was never one to make a meal of the various vicissitudes that came his way in life, being separated from his mother for five years at such a critical stage of his upbringing must have left its mark on him. It is certainly true that he grew extremely fond of his grandmother, and of Georgie and Nada, and was deeply appreciative of the homes that they provided for him, but at the same time they could never fully make up for the one he had lost. When, years later, an interviewer asked him what language he spoke at home, his immediate retort was, ‘What do you mean, “at home”?’

As far as Philip’s future wellbeing was concerned, it was fortunate that he had previously felt loved by both his parents and his nanny, and that he was thus a self-assured and happy child. According to the child psychologist Oliver James, this would have protected him to some degree from the psychological fallout of his mother’s breakdown and his father’s subsequent absence. ‘It would mean there was a kernel there, the basis for him to have been able to develop a more intimate and decent personality than is generally believed.’ However, James would still be inclined to question

whether having been part of a close family and having the whole thing smashed to pieces might have rather diminished his capacity to have faith in intimacy or love or closeness. The impact of having a mother go mad on you is to make you scared and also possibly fearful that the same thing is going to happen to you. If you throw in the disappearance of his father and being packed off to boarding school, which were pretty scary places in those days, you have a triple whammy, and there’s a fairly high probability that he would have developed what psychologists call a highly defended personality. That’s to say he doesn’t want to know about his emotions or other people’s emotions and he’s basically in survival mode – either he develops a pretty hard-nosed approach to life or he cracks up. He has to develop a false self to hide behind in order to avoid people knowing what he’s really feeling, and for himself, as he doesn’t want to know what he’s really feeling either. Obviously he was very handsome and no doubt he developed a very charming and attractive persona because he was probably all too aware that was necessary. But people like that, unless they’re very lucky, live in isolation all their lives although they don’t even know they’re doing it.

Philip would perhaps take issue with this analysis. However, in years to come, deprived of the constant loving attention of his parents, his emotional reserve would become as noticeable to friends as his bluff, controlled, no-nonsense exterior. His tendency to hide his feelings also meant that his occasional bouts of sensitivity and touchiness could take even those who knew him well by surprise.

SIX

Prep School Days

Boarding school offered one solution to the sudden dissolution of Philip’s family life. Andrea had wanted to send his son to school in England, hoping that he would receive a better education there than the harsh Greek military one he had experienced, but the actual choice of Cheam, England’s oldest prep school, was made by Philip’s new guardian, Georgie Milford Haven, whose father Louis had been sufficiently impressed by the manners of two Cheam old boys serving with him in the navy to send Georgie there, although not his younger son Dickie.

Georgie had in turn sent his son David to Cheam, and when Philip arrived his cousin was two years above. Listed on the register under his courtesy title, Earl of Medina, David was the only titled boy at the school at that time, although generations of nobility had attended the school since its foundation in 1645. One mid-nineteenth-century headmaster, Robert Tabor, had even gone to the trouble of devising graded modes of address for his various charges: when speaking to a peer, he would begin ‘my darling child’; with the son of a peer, it was ‘my dear child’; and with a commoner simply ‘my child’.

The more illustrious Cheam old boys included one prime minister, Henry Addington, one speaker of the House of Commons, two viceroys of India and Lord Randolph Churchill, the father of Winston, who was ‘most kindly treated and quite contented’ at the school, according to his son.

Perhaps not surprisingly, no great fuss seems to have been made of either of the royal children at the school while Philip was there, although, if anything, more was made of David Medina, as being more obviously one of the English royal family and aristocracy, whereas Philip was deemed to be foreign and therefore somehow slightly inferior.

Philip’s time there coincided with the school’s last years at Tabor Court in the Surrey village of Cheam, before the railway station and encroaching urbanization prompted the headmaster to sell up and move his school to its present site in the midst of the Berkshire countryside. His headmaster was Harold Taylor, a cheerful clergyman with a deep-seated affection for his boys. Forty when Philip arrived, Taylor was a product of Marlborough and Trinity College, Cambridge, a fine all-round athlete – albeit a heavy smoker – powerful swimmer and fearless horseman. He had served as a chaplain during the war in France, returning with shell shock and a military OBE. The boys called him by his initials, pronounced HMS T in line with the school’s strong naval tradition and his rolling gait which was said by some to resemble that of a ship in heavy seas.

After buying Cheam in 1921, Taylor and his vibrant wife Violet had insufficient funds to improve the spartan living conditions – prison-style beds, communal baths, ‘dog baskets’ to store the boys’ clothes – but they set about making it a more humane place in other ways. Boys with experience of the previous regime of Arthur Tabor were soon remarking on the ‘incredible change to friendliness’ after the Taylors took over. Philip himself retained fond memories of such school characters as Jane, the warm-hearted housemaid who scrubbed the boys’ backs at bathtime and made sure that their ears were clean; Major C. H. M. ‘Chump’ Pearson, Taylor’s unofficial deputy who ‘was far from scrupulous about his dress and habits’ and often taught lying back on the radiator with his feet on his desk; and W. J. ‘Molly’ Malden, the most popular of the masters, partly on account of his all-round athletic prowess, partly because he drove fast cars and flew a Puss Moth.

Taylor himself took games very seriously, but, with only seventy boys to choose from, Cheam struggled to compete against other schools. On the bus home from away matches the mood was often sombre as the headmaster brooded over yet another heavy defeat.

He had more success organizing non-sporting exercises for the whole school, such as pumping out the school swimming pool with an old manual fire-engine pump or beating for pheasants in the woods at Headley.

For all his bonhomie, Taylor was also a staunch disciplinarian, declaring sloth, dirtiness and untruth to be deadly sins, and resorting to corporal punishment at least as often as his peers, using a cane for daytime offences and a sawn-off cricket bat for those caught pillow-fighting after lights out. It was generally conceded that he beat ‘without rancour’, though some boys thought that he joked on the subject a little too readily. It was indicative of his reputation that when, shortly after Taylor retired, his one-time charge became engaged to the future Queen of England, the former headmaster was sent a rough rhyme:

Whoever of his friends then thought,

When, venturing, Cheam School he bought,

He’d lay his cane athwart

The bottom of a Prince Consort.

His first taste of this punishment as a new boy prompted Philip to ask the headmaster’s wife, ‘Do you like Mr Taylor?’ The experienced Mrs Taylor countered expertly, ‘Do you, Philip?’ she asked. ‘No,’ said the young boy unequivocally, ‘I do not.’

However, as time passed, Philip grew to like not only Mr Taylor but also everything else about Cheam, whose tough regime he later extolled in a preface to an exhaustive history of the school, published in 1974: ‘Children may be indulged at home,’ he wrote, ‘but school is expected to be a spartan and disciplined experience in the process of developing into self-controlled, considerate and independent adults. The system may have its eccentricities, but there can be little doubt that these are far outweighed by its values.’

His son, Prince Charles, who had a miserable time at Cheam, may not have entirely agreed with this credo, but Philip himself settled quickly into his new school. The headmaster’s son, Jimmy Taylor, who was at Cheam at the same time, says the fact of having arrived late (aged nine rather than the normal starting age of eight), with a ‘strange name and a shock of white hair’ ought to have made life difficult for the prince. There was an aura about him of ‘having arrived in England virtually an orphan and more or less friendless and speaking or certainly writing French better than he did English. So he was distinctly different from the other boys and must have been aware of that … But he was good at games so he was soon accepted.’

He remained, though, ‘quite private, not much given to confiding in others’. He was also physically strong and had a fairly quick temper, which deterred too much teasing, although he did get landed briefly with the nickname Flip-Flop. Another contemporary, John Wynne, remembers Philip as ‘extremely gifted’ but that he ‘didn’t show off his talents’. He was ‘a most charming person, very popular’.

‘When you think of all the problems he had being shovelled around, it was a remarkable achievement. He wasn’t bullied. Nobody would ever have had a poke at him, because they’d have got one back!’

Wynne remembered thinking that Philip had ‘tremendous confidence from somewhere’, and later, just before they left Cheam, while they were unpacking, seeing a photograph of George V beneath a pile of clothes in Philip’s trunk signed ‘From Uncle George’ which he had never displayed.

At the end of his first term at Cheam, Philip spent the 1930–31 Christmas holidays in Germany, where the festivities got under way on 15 December with the wedding of his sister Sophie and Christoph Hesse at Schloss Friedrichshof (now a five-star hotel) in the town of Kronberg in the Taunus foothills. Philip joined his sisters in helping to dress the excited Sophie in her room before the two ceremonies, Orthodox and Protestant, during which he carried her train. Their mother Alice was not there, feeling ‘not strong enough & too shy of strangers’, so Victoria told her lady-in-waiting, and after everything that had happened everyone felt sorry for Andrea, who ‘behaved splendidly’, reported Louise, although he ‘had the greatest difficulty not to break down’.

The wedding took place against a backdrop of deepening political crisis in Germany, Hitler’s National Socialists having established themselves as the main party of opposition in the Reichstag elections that autumn. Sophie’s bridegroom Christoph had long grown disillusioned with the Weimar Republic, whose laws repeatedly challenged the Hesses’ property and position, and his elder brother Philipp had signed up to the Nazi party in October 1930 – he would eventually come to be regarded as Hitler’s second closest friend after Albert Speer.

To begin with Christoph resisted following Philipp’s example, but he was just the sort of dashing type whom the Nazis proved so successful in recruiting – Hitler was obsessed with fast cars and planes, which sped him about between rallies, and National Socialism’s association with sports, adventure and modernity were big attractions to Christoph.

Within a year of his marriage to Sophie, he, too, had joined as a clandestine member, and by early 1932 he was in the SS and beginning to demonstrate ‘a discipline and a commitment to a cause that was unprecedented in his life’.

These developments doubtless seemed rather less sinister at the time than they do in retrospect and in any case they would almost certainly have meant very little to nine-year-old Philip, although they would have some bearing on his future – not least when it came to the question as to which of his family would be invited to his wedding. For the time being, after spending Christmas Day 1930 with uncle Ernie and aunt Onor at Darmstadt, on Boxing Day Philip was taken to see his mother at her sanatorium, he and his grandmother staying for a few days at a nearby hotel. The visit went smoothly enough, although Alice confided to Victoria that she did not think she had long to live.

A month later, on 8 February 1931, Philip attended the next family wedding, that of his other younger sister, Cecile, and Don Hesse. Some fifty relations gathered for the event at Darmstadt amid a densely packed and enthusiastic crowd of townspeople, who blocked Andrea and Cecile’s route to the church, and afterwards cheered the bride and groom on the balcony. ‘It seemed funny in a “republic”,’ wrote Victoria, ‘but was a nice sign of the affection of the people for Uncle Ernie & his family.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: