По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

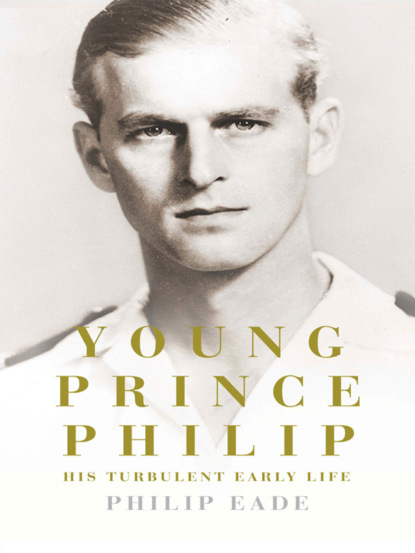

Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The housekeeper Agnes Blower later recalled Philip as ‘the sweetest prettiest baby’ with a healthy appetite. When he was a little older, she prudently ‘put a stop to his being fed on those messy foreign dishes which the Greek cook concocted’ and instead made him ‘nourishing rice and tapioca puddings and good wholesome Scots porridge’.

Andrea would have to wait several months before he saw his son. Having at last been given the command of a division, he had left Athens for Smyrna the day before Philip’s birth, accompanying his brother, King Constantine, who had placed himself at the head of his troops.

Cut off from Greece, the once great city of Smyrna had fallen into decline and their arrival served as a symbolic boost to its inhabitants, who cheered as Andrea and Constantine, the first Christian king to set foot on Anatolian soil since the Crusades, marched through the streets. Like the crusading kings, Constantine expressed his desire to lead the Greek army into battle, although in reality he was to be no more than a figurehead.

Andrea wrote despondent letters home about his own ill-equipped and inexperienced troops,

although he insisted that the Greeks as a whole would triumph in the end.

For a time his optimism seemed justified. With the Greek army sweeping all before it, the town of Kutahya, more than halfway towards Ankara, fell on 17 July. However, at this point the Turkish nationalist leader Mustapha Kemal (later better known as Atat?rk) shrewdly withdrew his main army intact.

Ankara now ‘beckoned like a mirage’ for the Greeks

and their determination to capture it was to lure them into a treacherous wasteland and fatally overstretch their lines of communication. The consequences of their doomed venture dramatically changed the course of Andrea’s and his family’s life. But before Alice and the others on Corfu apprehended all this, they received sad news from England.

The summer of 1921 had been a happy one for Alice’s sixty-seven-year-old father, Louis, who had been delighted by the birth of his grandson, Philip. In July he had chaired a Royal Navy Club dinner and hundreds of his brother officers had flocked from all corners of the country to what was usually a sparsely attended event. When he stood up to answer the toast there was a roar of cheering that lasted nearly five minutes, which so affected him that he was barely able to murmur his thanks. A fortnight later he learned that the king had promoted him to the rank of Admiral of the Fleet on the retired list, an honour accorded only once before. In late August, Louis went up to Scotland, where his younger son Dickie, then twenty-one, was serving in the battle cruiser Repulse. The week he spent on board at the invitation of the captain was his longest spell at sea for many years and he thoroughly enjoyed it. However, during the last three days he suffered from a chill and when he returned to London, his wife Victoria sent him to bed and called a doctor. While she went off to a chemist’s to fetch the medicine that the doctor had prescribed, a maidservant came to collect Louis’ tea tray, and found him lying serenely back on his pillows with his eyes closed. Victoria returned to be tearfully told: ‘Oh dear, Ma’am, the Admiral is dead.’

On hearing the news, Alice took Philip – who had thus been deprived of meeting the only one of his grandfathers still living at the time of his birth – over to England for the funeral. But they were still en route when Louis’ coffin was carried in a great military procession from the private chapel at Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey, with seven admirals and a major general of the Marines acting as pall-bearers. After the service he was taken by special train to Portsmouth and thence by destroyer to be buried on the Isle of Wight, where Alice and her son caught up with the rest of the family. Their first sight of three-month-old Philip was a welcome distraction for the mourners and Alice’s brothers took turns at cradling their future protеgе in their arms. When they eventually got back to Corfu, Alice was surprised to find Andrea at home on leave, following an escalating series of disagreements with his commander-in-chief.

The auguries for Andrea had not been good ever since he had arrived at the front. In his account of the Greek campaign in Asia Minor, aptly entitled Towards Disaster, he later alleged that the deficiencies of his troops had been part of a republican ploy whereby his division ‘would suffer disasters, in which case I would have borne the responsibility’.

To begin with his men had acquitted themselves surprisingly well, however, and in early August Andrea had been promoted to take command of the 2nd Army Corps. By this time, though, ‘all military prudence had vanished’, he wrote, and the ‘prevailing idea of GHQ was that the enemy no longer existed, and that an advance to Angora [Ankara] was only a military promenade’.

Even after crossing the Anatolian Salt Desert and capturing the strategically important Kale Grotto range, Andrea felt that the victory had been Pyrrhic. They had very little ammunition left and still less food. The horses in his division were dying for lack of fodder and there was no firewood for his soldiers to cook with.

Meanwhile the enemy had succeeded in withdrawing without any losses in prisoners or materiel.

The Greek military plans, drawn up by one Major General Stratigos, seemed to Andrea to be wrongheaded and contradictory. On more than one occasion he had deemed it prudent to carry out an alternative manoeuvre to that prescribed by headquarters. Eventually, however, when, during the battle of Sakaria, he refused to obey an order to attack, fearing it would be disastrous, his commanding officer General Papoulas decided he had had enough: ‘The only person competent to judge and decide is myself as Commander-in-Chief,’ he barked.

When Andrea then asked to be relieved of his command, the staunchly royalist general would not hear of it.

However, as rumours about Andrea’s supposed ‘lack of fighting spirit’ began to spread through the Greek ranks, Papoulas eventually granted him three months’ leave, whereupon Andrea made his way straight to Corfu.

His spirits were temporarily lifted by seeing his son for the first time, but after two months he gloomily returned to Smyrna. From there, on New Year’s Day 1922, he wrote to his friend Ioannis Metaxas bemoaning the impossibility of the exhausted Greeks holding their defensive line. ‘Something must be done quickly to remove us from the nightmare of Asia Minor … we must stop bluffing and face the situation as it really is. Because finally which is better? – to fall into the sea or escape before we are ducked?’

Andrea avoided the denouement he dreaded as he was posted in the spring to Janina in the province of Epirus in north-western Greece. On his way there, he spent Easter on Corfu, where Alice’s sister Louise and widowed mother Victoria had been helping to look after the children. The eldest, Margarita and Theodora, aged seventeen and sixteen, were ‘perfectly natural,’ wrote Victoria, ‘& Alice brings them up really well’.

She thought that Cecile, nearly eleven, would ‘certainly be the prettiest of the lot’ while seven-year-old Tiny (Sophie) was ‘great fun’ and ‘the precious Philipp the image of Andrea’.

Aged eleven months, Philip could ‘stand up alone now & sits with bare legs on the hard road & crawls on it without minding the stones. He is in fact as advanced & sturdy for his age as all the others were & has the same tow-coloured hair.’

Aunt Louise reported that her little nephew ‘laughs all day long. I have never seen such a cheerful baby.’

At the beginning of May, Alice accompanied Andrea to Janina and spent a couple of weeks there helping him to set up house.

Shortly after returning to Mon Repos, she travelled with her children on to London for the wedding of her younger brother Dickie Mountbatten to Edwina Ashley, granddaughter and heiress of the fabulously wealthy Jewish financier Sir Ernest Cassel. Dickie and Edwina had met in October 1920 at a ball at Claridge’s, hosted by Mrs Cornelius Vanderbilt, shortly after Dickie’s first love had broken off their engagement. Later that year they had been guests of the Sutherlands at Dunrobin Castle when Dickie received the news that his father had died. Within days Edwina’s grandfather was dead, too, and their shared bereavements brought them closer.

When, soon afterwards, Dickie travelled to India in the retinue of his cousin, the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII), Edwina joined him at the Viceregal Lodge in Delhi, where their courtship intensified beneath the disapproving gaze of the Viceroy’s wife, who, failing to foresee Dickie’s glittering future, hoped that Edwina would find someone ‘with more of a career before him’. At a St Valentine’s Day ball held by their hosts, Dickie asked Edwina to marry him and she said she would.

The magnificent wedding took place on 18 July 1922 at St Margaret’s, Westminster, with the Prince of Wales as best man. The congregation included King George V and an assortment of royalty and nobility from across Europe. Philip’s sisters were all bridesmaids, although Philip himself was left behind in the nursery of Spencer House.

A month later, on 26 August, they were all still in London when, with a thunderous roar of artillery, Atat?rk launched his devastating assault on the overextended Greek front in Turkey. Within a few days, it had turned into a rout, with the bedraggled Greek forces hurriedly withdrawing to the coast. They evacuated Smyrna on 8 September and the ensuing Turkish occupation of the city was accompanied by a massacre of some 30,000 Greek and Armenian Christians, a great fire which only the Turkish and Jewish quarters survived, and the flight of more than a million Greek refugees. It was a national humiliation on an epic scale.

As the remnants of the Greek army regrouped on nearby Aegean islands, a handful of colonels took charge and called for revolutionary action to purge the national shame. Their leader was Nikolaos Plastiras, one of Andrea’s least friendly subordinates during the campaign.

On 26 September an aeroplane flew over Athens demanding the resignation of the government and the abdication of King Constantine, a demand which Andrea advised his brother to accede to. Constantine was replaced by his eldest son, who ruled briefly and unhappily as King George II.

Andrea had been on leave in Athens as the disaster at Smyrna unfolded, and the British embassy reported that he had done his reputation with the Greek people no good by remaining ‘absent from his command in Epirus while such tragic events are happening to his country’.

It was subsequently understood that Andrea would now accompany the king into exile, the British ambassador, Francis Lindley, warning that any delay would be ‘most dangerous to their lives’.

However, when the king and queen slipped away from Greece in a grubby troopship bound for Palermo, Andrea was not with them.

Instead he had returned to Corfu to be with Alice and the children on their return from Dickie’s wedding, the revolutionary government having assured him that, providing he resign his commission, he and his family would be safe at Mon Repos. They soon found themselves more or less under house arrest, however, their movements and conversations monitored by police, their post opened and scrutinized. As the hunt for scapegoats for the Greek defeat intensified, they all worried about what might happen to Andrea.

In Athens, the new government set up a commission of inquiry into the disaster in Turkey, presided over by General Theodore Pangalos, Andrea’s old classmate from military college and now a ruthless staff officer ready to throw in his lot with the revolutionaries. The British embassy considered Pangalos ‘extraordinarily capable’ yet also ‘vindictive’, ‘a bad character’, ‘a fanatic’.

Eight of those held responsible for the military debacle – including two former prime ministers, ministers of the interior, war and foreign affairs and two generals – were soon arrested and on 23 October it was announced that they would be tried by a special court martial.

Three days later one of the revolutionary colonels came to Corfu in a destroyer and took Andrea back to Athens with him so that he could give evidence at the court martial. Andrea was told that he would be away for two days but after two weeks he had still not returned. Alice received a smuggled pencil note from him to say that he was being kept ‘strictly alone’ and was probably now going to be accused rather than appear as a witness.

He was being held under police guard at a private house and was allowed no visitors apart from his valet. All letters and parcels that arrived for him were confiscated and friends later reported that for three weeks ‘there was always the disagreeable feeling that death might come suddenly, perhaps in his quarters’.

One old lady had sought to console him by sending a foie gras in aspic, but even that was hacked to pieces before he was allowed to eat it. His brother Christopher managed to smuggle in a letter on cigarette paper which he hid among other cigarettes in the valet’s case, and in reply he received ‘a short note, full of courage’ describing a conversation Andrea had just had with his former schoolfriend. Out of the blue, Pangalos had asked, ‘How many children have you?’ When Andrea told him, Pangalos shook his head and sighed, ‘Poor things, what a pity they will soon be orphans.’

Meanwhile, the court martial of the other scapegoats began on 13 November 1922 in the parliament building in Athens, which was crammed with spectators, craning to catch a glimpse of the doomed men. They were all charged with high treason, for having ‘voluntarily and by design permitted the incursion of foreign troops into the territory of the kingdom’. In view of the very high probability that they would be shot, the British ambassador threatened to break off diplomatic relations if the revolutionaries failed to exercise clemency. At the Lausanne peace conference, the British foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, urged Venizelos, the former Greek prime minister, who was now an envoy for the revolutionary government, to do all he could to avert this ‘abominable crime’.

Curzon also had very much in mind the grave danger now facing Andrea, first cousin of George V, and he would almost certainly have been made aware in their meetings of the discomfort that the king still felt over the way he had allowed expediency to prevent him from giving sanctuary to his other first cousin, the tsar, in 1918. While there seems to be no conclusive evidence that George V took the exceptional step of exercising the royal prerogative to order the rescue of Andrea – as has sometimes been suggested – the king nevertheless later expressed the view that his cousin’s life had been saved ‘through his [George V’s] personal action’.

Whatever the precise nature of the king’s ‘personal action’, the result seems to have been that one Commander Gerald Talbot was soon on his way to Athens on a mission to reach an accord with the rebels.

This imperturbable forty-year-old naval officer, who had impressed Compton Mackenzie with his ‘great domed forehead’ and ‘the majestic stolidity of the demeanour it crowned’, had the crucial advantage of being a good friend of Venizelos.

Talbot had got to know him well while posted to Athens between 1917 and 1920, ostensibly as British naval attachе although effectively a spy. Reputed to ‘know more about the tortuous channels of Greek politics than most Greek politicians’,

Talbot was now part of Curzon’s delegation at Lausanne, with a specific brief to find out what his wily old Cretan friend was thinking.

When asked by Curzon what position he would be placed in, as the Greek government’s representative at Lausanne, if the threatened executions were carried out, Venizelos replied that he had already sent Talbot to Athens ‘to urge counsels of moderation on the revolutionary committee’.

Talbot, though, was presumably answerable to the Foreign Office rather than Venizelos, and he himself later maintained that he had undertaken his mission on the instructions of Curzon’s adviser, Sir William Tyrrell.

Wherever his orders came from, he was quickly on his way. When they got wind of this, the revolutionary government concluded the trial as quickly as possible, motivated partly by fears for their own safety if the defendants were not seen to be adequately punished.

The court martial opened on Sunday 26 November and at midnight on the Monday it rose to consider its verdict, which was delivered at 6.30 the next morning. All eight were found guilty of high treason. Six were sentenced to death, two to life imprisonment. By the time Talbot arrived in Athens at noon that day, 28 November, the condemned men were already dead. Their impassivity was ‘absolute’, according to one account. One former prime minister stared attentively at the firing squad; the former foreign minister put on his monocle after wiping it with his handkerchief; a general stood to attention; none of the six agreed to have his eyes bandaged.

Too late to save these wretched men, Talbot concentrated his efforts on Andrea, whose own court martial was due to begin on 30 November and whose position Lindley, the British ambassador, now deemed ‘much more dangerous’ since the executions.

The ambassador left Athens that evening in accordance with his threat to break off diplomatic relations, but before going he met Talbot and they agreed that a show of force such as the presence of a British man-of-war would do more harm than good. Instead Lindley suggested that Talbot should consider the possibility of bribery.