По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

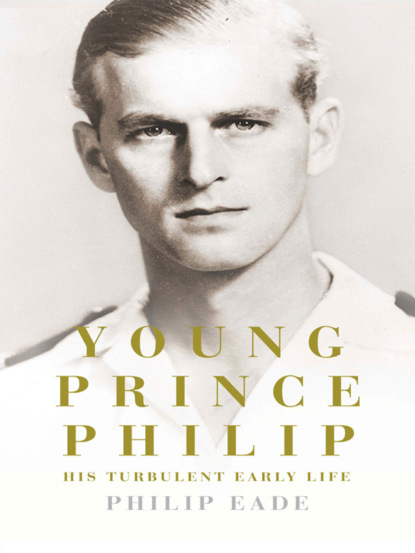

Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Talbot promptly went into a series of long and secret meetings with the rebel leaders, Colonel Plastiras and General Pangalos – by now minister of war. On 30 November the British counsellor was able to report that Talbot had obtained a promise from them ‘that Prince Andrew will not be executed but allowed to leave the country in the charge of Mr Talbot’. The arrangements agreed upon were that:

Prince will be tried on Saturday and sentenced probably to penal servitude or possibly to death. Plastiras will then grant pardon and hand him over to Mr Talbot for immediate removal with Princess by British warship to Brindisi or to any other port en route to England. British warship must be at Phaleron by midday on Sunday, December 3rd and captain should report immediately to legation for orders, but in view of necessity for utmost secrecy, captain should be given no indication of reason for voyage. This promise has been obtained with greatest difficulty and Talbot is convinced it is essential that above arrangement be strictly adhered to so as to save Prince’s life. As success of plan depends upon absolute secrecy of existence of this arrangement, even Prince and Princess cannot be given hint of [what is] coming. Talbot is convinced that he can rely on word given him and I see no other possibility of saving Prince’s life.

On 2 December Andrea went on trial in the parliament building, charged with disobeying an order during the battle of Sakaria and of abandoning his post in the face of the enemy. His commander-in-chief General Papoulas and another officer were called to give evidence, the latter asserting that the battle would have been won had the order been obeyed. During the course of the proceedings Andrea wore civilian clothes and one American journalist observed that he thus ‘failed to give the impression of a virile general defending his actions during the war’.

The court martial found him guilty and he was sentenced to degradation of rank and banishment for life, escaping the death sentence only, as it was stated for public consumption, due to ‘extenuating circumstances of lack of experience in commanding a large unit’.

On the afternoon of Sunday 3 December Pangalos quietly escorted Andrea and Talbot to the quay at Phaleron, where Alice was already waiting aboard the British light cruiser Calypso. The departure had been arranged in the strictest secrecy, so there were no crowds to send them on their way, although a few boatmen recognized Andrea and greeted him.

Taking leave of the British counsellor who accompanied him to the pier, Andrea requested that he ‘convey to His Majesty’s Government his deep gratitude for their efforts on his behalf’.

The same counsellor later drew Curzon’s attention to the ‘great services’ rendered by Talbot. ‘I believe that he has succeeded in checking the Greek Government in their course of madness.’

The next day, en route for southern Italy, they called in at Corfu to pick up their four daughters and young son, along with Nanny Roose, two maids and a valet.

Philip’s youngest sister Sophie recalled their hurried departure as ‘a terrible business, absolute chaos’, and many years later she could still smell the smoke from the grates in every fireplace at Mon Repos as her elder sisters burned all their letters and documents before gathering together a few possessions and then being bundled into cars and then a small boat to the cruiser, anchored offshore.

Philip remembered nothing at all about the whole episode.

FOUR

Family in Flight

During the passage to Brindisi, several officers of Calypso vacated their cabins for Andrea and Alice’s family, and the crew fashioned a crib from a fruit crate for the eighteen-month-old Philip to sleep in. It was a rough crossing and some of them were sick, yet Andrea nevertheless struck the captain as ‘delightful, and so English’, and all the family were ‘rather amusing about being exiled, for they so frequently are …’

Their apparent insouciance belied the strain that they had been under.

On arrival in Italy, they continued by train, with the infant Philip crawling all over the carriage and licking the window panes, oblivious to the drama. At Rome, they thanked the Pope for his help in securing their release.

The British ambassador lent them 14,000 lire and private arrangements were made for their entry into France, as they had no passports either.

An extra sleeping carriage was then attached to the overnight express to Paris, where they arrived on 8 December and went straight to the hotel apartment of Andrea’s brother Christopher. Thereafter a tense Andrea ‘denied himself to all callers’, instructing the hotel management that no one be permitted even to send up a card.

Talbot had promised Plastiras and Pangalos to take Andrea straight to London – or else more executions were threatened – but there was nervousness in London about members of the Greek royal family suddenly turning up, especially while Parliament was sitting, and the prime minister (Bonar Law) wrote urging George V not to encourage them to settle in England.

The king was only too happy to assent to this. As he saw it, he had already saved Andrea’s life, and bearing in mind the antagonism directed towards him the last time the Greek princes came to London, during the war, he felt that Andrea and his family should not ‘unduly estimate the inconvenience’ of remaining in Paris until after Parliament had prorogued.

While they waited there, Talbot went on ahead to London to make his report, and was promptly knighted by the king for his role in rescuing his cousin.

On 17 December, with Parliament in recess, Andrea and Alice and their family slipped into Britain at Dover, their arrival going unnoticed by the British press. Likewise, when Andrea went to see George V two days later,

his visit was not advertised in the Court Circular. Their experiences over the past few months had visibly aged both him and his wife. Photographs from the time show the monocled Andrea looking far in advance of his years, his furrowed brow a manifestation of the ordeals he had been through, while Alice’s sister Louise was shocked at how worn out she looked compared to the previous summer, when she had come over for Dickie’s wedding.

Still smarting at his treatment, Andrea told an American newspaper that he had

ample documentary material for an appeal, and when the right time arrives I hope to publish the facts. Then the people of my country can judge for themselves whether I was rightly convicted. At present all the evidence that reaches me is convincing that the Greeks as a whole disagree with what has happened. I believe I can say without egotism that the nation is in sympathy with me, and I am confident that, when hot passion and political prejudice have subsided somewhat and my statement of my case is placed before them, the people will decide in my favour.

However, the American chargе d’affaires in Athens said that it was ‘a great mistake’ that Andrea and his brothers were ‘carrying on a kind of propaganda abroad against the present regime in Greece and abusing them quite openly wherever they go’. Not only did it annoy those in power and make them more hostile to the exiled princes’ nephew, the king, but it was also particularly ill timed at a moment when private promises had been extracted through diplomatic channels to respect Andrea’s property and possessions on Corfu.

Andrea was still undecided as to where they were going to live, but planned in the meantime to visit his brother Christopher in America.

As guests of his brother, he and Alice could at least expect to be well looked after, not least since Christopher’s wife, Nancy, was extremely rich, having inherited a fortune from her first husband, the tin-plate tycoon William B. Leeds, when he died in 1908.

After spending Christmas with Victoria at Kensington Palace, Andrea and Alice sailed for New York in January 1923, leaving the two elder girls, Margarita and Theodora, with their grandmother in England

and the two younger ones and Philip with their uncle, Prince George of Greece, and his wife, Marie Bonaparte, in Paris. In mid-Atlantic news reached them that Andrea’s brother, Constantine, had died in Sicily. The exiled king’s death had met with a subdued reaction in Athens. ‘A few weeping people were loitering outside the gates of the Palace the next day,’ reported the British counsellor, but otherwise, ‘tears were shed in private houses.’ His name, wrote the counsellor, had been inextricably linked in the minds of the Greek people with the dream of Constantinople, and at one time he had acquired a popularity unattained by any of the other kings of Greece. But parallel to this, ‘he was hated by a constantly varying number of his fickle subjects’ and ‘rightly or wrongly, he was accused of having sympathised entirely with Germany during the war’.

Andrea and Alice arrived in New York dressed in mourning clothes. After they landed, Christopher took them straight up the Woolworth Building, at that time the tallest structure in the world, for a panoramic view of the city. Andrea bought models of it to give to his children and to the waiting reporters he enthused about New York’s skyscrapers. He also pronounced the outfits worn by American women ‘very neat indeed’. The reporters were curious about their small entourage – consisting of only a valet and a maid – and when one of them asked Andrea why he did not have a gentleman-in-waiting to attend to social matters, he laughed and replied: ‘I’m a democrat!’

Andrea and Alice stayed in America for two months, during which time they travelled by train to Montreal to attend a memorial service for King Constantine,

and also spent time in Washington, DC, and at Palm Beach in Florida with Christopher and Nancy – who did not let on that she was dying of cancer – before sailing back across the Atlantic on 20 March. As he prepared to board the Cunard liner Aquitania, Andrea told the press that he would not ‘risk the chance of being executed’ by going back to Greece.

The prospect of living in Britain among a suspicious and rather hostile people did not greatly appeal either – George V would presumably have intimated to Andrea the difficulty of their staying there when he saw him in December – and so instead they decided to settle in Paris, which was already home to a cluster of Greek and Russian еmigrе royalty and would remain their base for the remainder of the decade.

To begin with they were lent a suite of rooms in a palais on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, but Andrea found he could not afford the household that came with it, so they soon moved across the Seine to a small lodge in the garden of 5 rue du Mont-Valеrien, in the smart hilltop suburb of St Cloud, six miles west from the city centre and commanding spectacular views eastwards towards Montmartre and the Eiffel Tower. Both properties belonged to Marie Bonaparte, Princess George of Greece, the wife of Andrea’s elder brother, an intriguing figure known in the family as ‘Big George’. His eventful career had included a spell in the Greek navy – during which he acquired a quarterdeck vocabulary in four languages

– and a period as high commissioner of Crete. Earlier he had saved the life of his cousin, the future Tsar Nicholas II, by parrying the sabre of a would-be assassin in Japan.

Marie herself was a restless, exotic woman, destined shortly to become one of Sigmund Freud’s leading disciples and benefactors, and thus central to the establishment of psychoanalysis and sexology in France. She was the great-granddaughter of Napoleon’s renegade younger brother Lucien, although her great wealth came from her maternal grandfather, Fran?ois Blanc, who had accumulated a vast fortune from property in Monaco and as owner of the casinos at Monte Carlo and Homburg. She had been in love with the tall and handsome Big George when they married in 1907, she aged twenty-five, he thirty-eight, but she soon became disillusioned on account of his disinterest. For one thing, he refused ever to let her kiss him on the lips and their wedding night, she recorded, culminated in ‘a short, brutal gesture’ from him and an apology: ‘I hate it as much as you do. But we must do it if we want children.’

By the time Andrea and his family came to live in the grounds of their large mansion at St Cloud, where Marie had been born, Marie and George were spending much of their time apart, she carrying on with a succession of lovers, most recently the French prime minister, Aristide Briand, he often away in Denmark with his father’s younger brother Waldemar, ten years George’s senior and the love of his life.

George had formed this unusual attachment after being entrusted to his uncle’s care at the age of fourteen, when he enrolled at the naval academy at Copenhagen. Standing on the pier where his parents’ ship was preparing to depart, he had suddenly been overwhelmed by feelings of abandonment, feelings which had then been allayed when Waldemar took his hand and walked with him back to his residence. ‘From that day,’ Big George later told Marie, ‘from that moment on, I loved him and I have never had any other friend but him.’

On their wedding night in Athens, according to Marie, George came to her room having first visited that of his uncle, and she later wrote to her husband that ‘you needed the warmth of his voice, of his hand, and his permission to get up your courage to approach the virgin’.

Waldemar accompanied them on the first three days of their honeymoon and George cried as they parted at Bologna. In later years, their children would become so used to seeing their father together with his uncle that they took to calling Waldemar ‘Papa Two’.

The house that Marie lent Andrea and his family was pleasantly surrounded by apple trees and gravel paths but had barely enough room for the family and their small staff. (It has since been demolished, along with Marie’s mansion, to make way for modern blocks of flats.) Philip’s sister Sophie later remembered that ‘there were always problems paying the bills’, although George and Marie’s son Peter was under the impression that his mother ‘paid all their expenses for years’.

The extent of the family’s penury at this time is unclear. On arrival in London, Andrea told one newspaper that he had managed to bring some money with him from Greece,

although Philip later doubted that he had ever received his army pension.

He had a small bequest from his brother Constantine, and before that he had inherited an annuity from his father as well as Mon Repos, where the Blowers and their unfriendly dogs had stayed on as caretakers, antagonizing the local population by denying them access to the only good bathing spot near to Corfu Town.

Andrea continually worried about the threat of confiscation hanging over Mon Repos, however, and in May 1923 he wrote to his saviour Gerald Talbot refuting the notion that he was going about criticizing the revolutionary government in Greece. ‘Since I am in Paris I see nobody and I go nowhere,’ he pleaded. However, he suspected that others

wish to believe or rather make others believe the story of my dark doings abroad in order that they may lay hands on my property. I am awfully sorry to bother you with all this, but you are the only one who can help me and I hope you can see your way to letting the Foreign Office in London know that I flatly and absolutely deny the charge of carrying on any kind of propaganda. It would be idiotic of me anyhow to poke spokes in [the British counsellor] Bentinck’s wheels while he is trying his level best to save my house in Corfu!

On the same day, he shot off another letter to Bentinck in Athens, expressing himself ‘astonished’ by the American chargе d’affaires’ suggestion that he had been spreading propaganda. ‘I cannot think where he gets his information from. I went to America to recuperate, and I can assure you that I did what I could to forget politics, revolutions and wars. When I was asked by newspaper men whether I had been imprisoned and in danger of my life, I answered in the affirmative because I could not very well tell them that I had been perfectly free … I’m afraid you will have to take my word for it.’

In the event, Mon Repos never was confiscated, although many Greeks continued to believe that it rightfully belonged to the Greek state, as it had originally been given to ‘the King of the Hellenes’, and was not transferable.

In 1926 Andrea leased the house to Dickie Mountbatten, providing a modest extra source of income, and in 1937, having won a legal case over its ownership, he sold it to his nephew, King George II.

Alice, meanwhile, had inherited a tenth of her father’s estate, but this had been substantially depleted by the Bolshevik revolution and the catastrophic inflation and currency devaluation in Germany – which effectively wiped out the proceeds from the recent sale of Heiligenberg Castle, where her father had spent his youth. She also received a small allowance from her brother Georgie. However, by royal standards, the family was certainly not well off.