По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

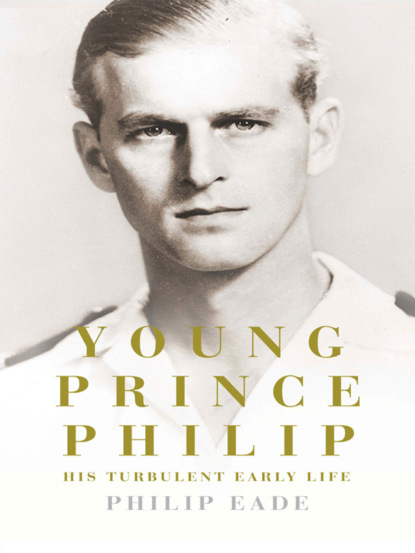

Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Alice was inspired to become a nurse by the example of the grandmother whose name she had been given and more recently by the extraordinary precedent of her aunt Ella, Victoria’s younger sister. Ella was married to Tsar Alexander III’s brother, Grand Duke Serge Alexandrovich, the reactionary and widely disliked governor-general of Moscow. In February 1905 Serge had been blown to pieces by a terrorist bomb thrown at his carriage in the Kremlin. Hearing the explosion, Ella had rushed to the scene and, kneeling in the snow, calmly helped gather up his scattered remains, though other parts were later retrieved from nearby rooftops.

The murder brought about a profound change in Ella. Shortly afterwards she visited the assassin at the police station and vainly pleaded with him to repent. She withdrew from society, turned increasingly to her adopted Orthodox faith, became a vegetarian, gave away her jewels and furs, and – inspired by her mother’s ‘Alice Nurses’ at Darmstadt – opened a charitable convent where she lived as the abbess, sleeping on a bare wooden bed with no mattress and one hard pillow, and tending patients herself in the hospital wing. She founded a home for consumptives and an orphanage, and during the October Revolution in 1905 stole out of the besieged Kremlin each day to tend to the wounded in hospital.

Alice had seen for herself her aunt’s work when she visited Russia, and it made a deep impression on her. Since first arriving in Athens she had spent much of her time at the charitable Greek School of Embroidery and at the outset of the First Balkan War she had the school make 80,000 garments for the troops and refugees.

Then, leaving her three young daughters – her third, Cecile, had been born in 1911 – she went with Andrea and his brothers to Larissa, where in a burst of manic energy she established a hospital after finding that the army had no plan for one. ‘I myself forced the Military Authorities to fit out an operation room in 24 hours,’ she wrote to her mother.

Realizing it was taking fourteen hours for the wounded to be transported from the front, she then moved her hospital to the recently liberated town of Elassona at the foot of Mount Olympus, requisitioning a school and raiding Turkish houses for mattresses and bedding for 120 men. Alice was in the thick of it, changing bandages on ‘ghastly’ wounds, helping the doctors in ‘fearful operations, hurriedly done in the corridor amongst the dying and wounded waiting for their turn’, with barely any light, the battle still raging all around them, and scarcely any time for sleep between each batch of arrivals. ‘God! What things we saw!’ she wrote. ‘Shattered arms, and legs and heads, such awful sights – and then to have to bandage those dreadful things for three days and three nights. The corridor full of blood, and cast-off bandages knee high.’

She soon expanded her hospital, taking over four more houses and later, as the Greek army advance continued northwards, she moved on to Kozani, where on one occasion she found herself assisting at the amputation of a leg, administering chloroform and preventing the patient from biting his tongue. ‘Once I got over my feeling of disgust, it was very interesting, of course,’ she assured her mother. When the operation was over, the leg lay abandoned on the floor of the ward and Alice suggested someone ought to take it away. Her assistant duly picked it up, ‘wrapped it up in some stuff, put it under her arm and marched out of the hospital to find a place to bury it in. But she never noticed that she left the bloody end uncovered, and as she is as deaf as I, although I shouted after her, she went on unconcerned, and everybody she passed nearly retched with disgust – and, of course, I ended by laughing.’

As the Greeks pressed on through the snowy mountains towards Salonika, the capital of Macedonia, determined to wrest it from Turkish control before the Bulgarians did, Alice remained constantly at or near the front. In each place she passed through she left a well-organized hospital, work for which she would later be personally thanked by prime minister Venizelos.

On 12 November 1912 Venizelos accompanied the king and his heir as they rode in triumph through the streets of Salonika. There was great rejoicing throughout Greece, and Alice and Andrea went to stay with the king, who had installed himself in the Sultan’s villa in the city. In March 1913 Janina, the capital of Epirus, also fell to the Greeks – witnessed by Alice who was again organizing the hospitals – and by the end of the Second Balkan War that summer, which began when the Bulgarians ill-advisedly attacked both Greece and Serbia, Greece had almost doubled in size and population, having gained southern Epirus, Macedonia, Crete and some Aegean islands.

After the tribulations of recent years, these territorial gains were a source of great relief and happiness to King George, and at lunch one day, on 18 March 1913, he announced that he now intended to abdicate on his golden jubilee in October, leaving his newly popular and auspiciously named son Constantine to succeed him. As the lunch party broke up, one of the generals present ventured to warn the king that his habit of strolling freely about the streets was perhaps more dangerous in Salonika than it was in Athens, to which the king replied that he did not wish for such a sermon. Later that afternoon, accompanied by his equerry and two policemen, the king set out for his usual walk to the White Tower. On his way back, as he passed a cafе, a man came out and shot him dead with a revolver. The assassin turned out to be an insane Greek rather than a Bulgarian or Turkish nationalist as had been feared, and he subsequently leapt to his death from a window while awaiting trial.

King George I’s body was carried by sea to Athens, from where a train took the coffin to Tato?. Crowds of peasants collected alongside the track and knelt as the train passed.

The British ambassador reported that

Tragic as was the manner of the King’s death, he was at least happy in the moment of it. He had seen the edifice he had laboured to construct for 50 years crowned by the victories of his army under the leadership of his son and successor. He had the assurance that his dynasty was at least firmly seated upon the throne which he had often during his long reign been tempted to abandon in despair. He had seen his aspirations realized beyond his wildest dreams. He will live on in the memories of his people as a martyr to the national cause.

King George’s son was now hailed in some newspapers as Constantine XII, successor to the last Greek ruler of Byzantium who had died during the siege of Constantinople in 1453, although in fact he ascended the throne as Constantine I. The British ambassador deemed him ‘inferior in intelligence to his father, and wanting in his dexterous pliability’, yet at the same time ‘a man of stronger character’ who ‘may well be fitted to deal with the new problems which will arise in the new situation’.

His reign was to prove rather less happy and considerably less enduring.

One of Constantine’s handicaps was that he had married Princess Sophie of Prussia, the sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II. On the outbreak of the First World War he was thus torn between loyalty to his wife and a feeling that Germany might win on the one hand, and pressure to join the Allies on the other. His decision to stay neutral placed Greece at odds with both sides and thereafter lowered the Greek royal family in the estimation of the British people.

The outbreak of the European war placed Alice, born a German princess yet with her father serving as Britain’s First Sea Lord, in a similarly awkward position. Louis of Battenberg had been responsible for mobilizing the British fleet prior to the war and on 4 August 1914 he sent the signal: ‘Admiralty to All Ships. Commence hostilities against Germany.’

By then he had served for forty-six years in the Royal Navy, yet his accent and mannerisms were still faintly German, and he kept German staff in his household. Within the navy, he was acknowledged as an exceptional sea officer and Fleet Commander, and a kind and courtly man; however, his insistence that there were certain things that were done more efficiently in his country of birth inevitably aroused hostility towards him.

Following the outbreak of war, the British popular press whipped up a wave of scurrilous anti-German paranoia, during which anyone or anything deemed to be of German origin was liable to come under attack. Shop windows were smashed, dachshunds were kicked in the street and innocent people with Teutonic-sounding names were arrested and imprisoned without trial. When two German cruisers mysteriously evaded a British force in the eastern Mediterranean and made it to Constantinople, it was whispered that a British admiral must have assisted them and that Louis Battenberg was a German spy. Of course, George V, too, had a German name and connections, and the wholeheartedness of his commitment to the Allied cause also came under scrutiny. On one occasion, Lord Kitchener ‘had solemnly to assure the Cabinet that lights seen flashing over Sandringham during a German air sortie were caused by the car of the rector returning home after dinner’.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, attempted to make light of all the xenophobic hysteria, and when told off for drinking hock, he responded: ‘I am interning it.’

Nevertheless, he worried about the effect of all the attacks on his First Sea Lord’s powers of concentration, and soon decided that the country’s best interests would be served by replacing Louis with the more dynamic Admiral ‘Jacky’ Fisher.

It was with some relief, therefore, that he accepted Louis’ resignation on 29 October 1914, even though it deprived the Royal Navy of one of its shrewdest strategic brains.

The whole episode was a great tragedy for Louis. ‘I feel for him deeply,’ wrote George V in his diary, ‘there is no more loyal man in the country.’

However, Battenberg’s younger son, also called Louis but known in the family as Dickie, then a fourteen-year-old naval cadet at Osborne, casually remarked to a contemporary: ‘It doesn’t really matter. Of course I shall take his place.’

His vow to avenge the family’s humiliation would propel him on a career path even more remarkable than that of his father.

During the early part of the First World War, Andrea was stationed at Salonika, but in 1916 his brother King Constantine sent him on a diplomatic mission to London and Paris to assure the Allies that Greece was not on the German side. Alice remained mostly in Athens, looking after their four daughters. The youngest of these, Sophie, had been born in 1914 and was always known in the family as Tiny, although she grew to be the tallest of the four sisters. Shortly after her birth her teenage uncle Dickie had written to his mother, Victoria: ‘Please congratulate Alice from me, but it was silly not to have a boy for once in a way.’

The political situation in Greece remained fraught throughout the war. Venizelos favoured siding with the Allies, thinking that they would win and be more sympathetic towards Greece’s remaining territorial ambitions. He also considered the Allies’ superior naval power vital to the protection of his maritime country. In 1916 he staged a coup and established a rival government in Salonika, which promptly declared war on Germany. When King Constantine continued to insist on Greek neutrality, the Allied fleet bombarded Athens.

Alice was at the embroidery school at the time and drove home ‘through a rain of bullets’ to find one of the nursery windows shattered by a shell. She quickly took her children down to the palace cellar, where Constantine’s queen Sophie was also sheltering.

During the subsequent blockade they both worked in soup kitchens. Eventually, in June 1917, Constantine bowed to Allied demands that he leave the country, a humiliating finale to a reign that had begun with such high hopes.

While the banished king made his way to Switzerland accompanied by his eldest son, Crown Prince George, whom the Allies also considered too pro-German, he was succeeded by his second son, Alexander. The other brothers, including Andrea, were soon asked to follow Constantine into exile, and Andrea and Alice were thus condemned to another spell of kicking their heels, this time at a hotel in St Moritz and later in Rome.

Alice’s parents in England, meanwhile, suffered further upheavals of their own. In the summer of 1917 George V decided to camouflage the royal family’s Germanic associations by renaming his dynasty the House of Windsor. Absurdly, no one in Britain seemed able to agree on what the previous name was, although the Kaiser declared that he was looking forward to attending a production of ‘The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha’ – one of his only recorded jokes. The king accompanied his change of name with a request that other members of the royal family relinquish all of their German names and styles and titles.

Alice’s father, His Serene Highness Prince Louis of Battenberg, thus found himself relegated to being the Marquess of Milford Haven, while his family name was translated into English as Mountbatten. He admitted to finding the change ‘a terrible break with one’s past’

and while staying with his elder son Georgie when his new title was announced, he wrote sadly in the visitors’ book: ‘Arrived Prince Jekyll, Departed Lord Hyde’.

Yet Louis’ predicament was mild compared with the branch of his family in Russia, where the tsar had been forced to abdicate following the outbreak of revolution in March 1917. George V, the tsar’s first cousin, briefly considered giving him sanctuary but then had second thoughts, fearful that his apparent endorsement of the old tsarist regime would antagonize Russia’s new rulers, who remained Britain’s allies in the war.

The offer of asylum was thus withdrawn.

In April 1918 the tsar and tsarina (Alice’s aunt Alix, who had become deeply unpopular in Russia due to her perceived Germanic aloofness and devotion to Rasputin) and their teenage children were taken to Ekaterinburg in the Ural Mountains, where three months later they were executed. Alice’s other aunt, Ella, had carried on with her selfless work, refusing all offers of asylum from abroad. In 1918 she, too, was arrested by Lenin’s secret police and taken with other members of the imperial family and their retainers to the mining town of Alapayevsk, one hundred miles from Ekaterinburg. One night they were woken up and told to get dressed. They were then blindfolded and their hands tied behind their backs before being driven to the edge of a mine shaft, where they were thrown in. They were heard saying prayers until, it seems, they were eventually killed by a combination of hand grenades and burning brushwood. The martyrdom of Ella in particular (she was later recognized as a saint) would have a profound influence on the future course of Alice’s life – and by extension that of Prince Philip.

The new Greek king, Alexander, had reigned for only three years when, in October 1920, he was out walking his wolfhound, Fritz, in the garden at Tato? and the dog was attacked by a tame Spanish monkey. While trying to release the monkey from Fritz’s teeth, the king was attacked by its mate and severely bitten in the leg. The wound was quickly cleaned and dressed but after two days a fever set in. Three weeks after that the king died from blood poisoning, aged twenty-six, leaving a young and beautiful widow, Aspasia, who was five months pregnant with their daughter Alexandra, Philip’s cousin, childhood friend and future biographer.

Winston Churchill later remarked that it was perhaps no exaggeration to say that ‘a quarter of a million persons died of this monkey’s bite’ – an allusion to Greece’s subsequent military campaign in Turkey, which was led by Alexander’s father Constantine, who returned to the throne after his son’s death. In the lead-up to this latest adventure, fearing Italian encroachment in the region, the Allies had agreed to the landing of Greek troops in Smyrna (now Izmir, on the west coast of Turkey), the wealthiest of Ottoman cities and the embodiment of that empire’s reputation for cosmopolitanism and religious tolerance. Smyrna had more Greek inhabitants than Athens and had been a long-cherished objective of Greek nationalists. In June 1920 the Greeks had advanced further into Turkish territory and in August, under the Treaty of S?vres, they had gained Thrace while their administration of Smyrna and its hinterland had been extended for a further five years – after which the region was to be annexed if the local parliament so decided. Venizelos’s supporters boasted of having created a Greece of ‘the two continents and of the five seas’.

After King Alexander’s death, his younger brother Paul was invited by Venizelos to assume the throne, but he refused on the grounds that his father and elder brother had never renounced their prior rights. Venizelos then called a general election in November 1920 in which he offered the Greek people the freedom to vote for the restoration to the throne of Alexander’s father, the exiled King Constantine. To the amazement and dismay of virtually all foreign observers they did so, decisively removing Venizelos and his government from office in the process.

Andrea, by now balding and wearing a monocle, was at last able to return to Greece from Rome with his family. On arrival at Phaleron Bay he and his brother Christopher were ‘borne on the shoulders of the populace, frenzied with joy’ all the way to Athens, so Alice recorded, and he was then required to make a speech from the balcony of the royal palace ‘to the vast crowds gathered below’.

A month later, on 19 December, King Constantine returned from exile to the throne amid much Greek rejoicing – although the Allies refused to recognize him.

Having previously criticized the campaign in Turkey, once in power it soon became clear that the new royalist government now planned to continue it with a spectacular offensive eastwards from occupied Smyrna towards the towns of Kutahya and Eski Shehir in the heart of Anatolia. ‘The morale of the army, its spirit and its certainty of success are high,’ wrote King Constantine. ‘God grant that we may not suffer disappointment! It will be a very hard struggle, which will cost us enormous sacrifices; but what a triumph if we win!’

Andrea returned to the Greek army in the rank of major general and after years of depressing inactivity he was raring to go.

THREE

Boy’s Own Story

Alice had by this time just become pregnant again. When she told her parents the news three months later, in February, she was reposing at Mon Repos, the Regency villa on the island of Corfu that Andrea had inherited from his father. Originally built for the British high commissioner, the house stood in grounds scented with eucalyptus and cypress, looking out across the Ionian Sea towards Albania and northern Greece.

Unoccupied during their three years away from Greece, it was sparsely furnished and almost entirely lacking in modern comforts – there was still no electricity or gas or running hot water or central heating – however, after the traumas of the past few years, its seclusion made it the ideal place for Alice to await the birth of her fifth child. Andrea had remained in Athens, imploring the military authorities to give him a command in Turkey, but Alice had their four daughters with her, along with a Greek cook and cleaner, an English couple who acted as housekeeper and handyman, and an elderly English nanny, Miss Roose, who had once nursed Alice herself and now ordered in stocks of baby foods and clothes from London

in anticipation of the new arrival, which everyone was hoping would be the longed-for boy.

Alice went into labour on 10 June 1921 and was taken by the Corfiot doctor to the dining-room table, which he deemed the most suitable place in the house for this thirty-six-year-old princess to give birth. At 10 a.m., a baby boy was delivered. Registered in nearby Corfu Town under the name of Philippos, he was sixth in line to the Greek throne.

‘He is a splendid, healthy child, thank God,’ Alice wrote three weeks later to her aunt Onor

at Darmstadt. ‘I am very well too. It was an easy delivery & I am now enjoying the pleasant fresh sea air on the chaise-longue on the terrace.’ In Andrea’s absence, she had to answer the ‘piles of telegrams’ herself, dictating three to four letters a day.