По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

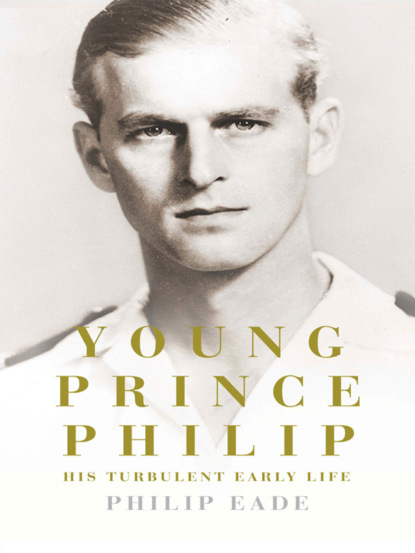

Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Although George liked discipline and uniforms, he was in other respects a relatively down-to-earth monarch, and the atmosphere at his court was generally far more relaxed than elsewhere in Europe. The princes and princesses were known by their Christian names alone and often hailed as such in the street. They all grew up with a love of practical jokes. ‘Anything could happen when you got a few of them together,’ according to Philip. ‘It was like the Marx brothers.’

Court balls were notably democratic. A foreign guest once hired a carriage to drive him to the palace for one of these parties, only for his coachman to stipulate: ‘Do you mind going rather early, because I’m going there myself and shall have to go home and change?’ The foreign gentleman laughed at what he thought was a rather good joke; but later in the evening, there was his driver, resplendent in evening clothes, dancing with the wife of a minister.

There was a fairy-tale quality to the whole set-up. When E. F. Benson visited in 1893 he recorded that on Sunday afternoons a small compartment was often reserved on the steam tram that ran between Athens and the coast at Phaleron; when it stopped opposite the palace, the king and his family would emerge to the sound of a bugler. If they failed to come at once, the driver would impatiently touch the whistle. Benson found Greece to be an

astonishing little kingdom, the like of which, outside pure fiction, will never again exist in Europe … its army dressed in Albanian costume (embroidered jacket, fustinella, like a ballet skirt, fez, white gaiters, red shoes with tassels on the toes like the seeds of dandelions), its fleet of three small cruisers, its national assembly of bawling Levantines and its boot-blacks called Agamemnon and Thucydides, was precisely like the fabulous kingdom of Paflagonia in The Rose and the Ring, or some Gilbertian realm of light opera.

Every other summer the family would travel to Denmark, where King Christian IX and his wife Queen Louise had their descendants to stay en masse at the vast Fredensborg Palace. With all the court attendants and personal servants, the house parties numbered up to three hundred, and apart from the Greek royal family, included the Prince and Princess of Wales and Tsar Alexander III and Tsarina Marie Feodorovna (as King George’s sister Dagmar had now become). Court etiquette was dispensed with during the day, when the tsar would take the children off to catch tadpoles or steal apples, but for dinner they all entered the big hall in a long procession arm in arm, preceded by the tsar, who offered his arm to Queen Louise, and the rest following according to rank.

There were also regular trips to Russia – across the Black Sea to Sebastopol where the luxurious imperial train awaited – and to Corfu, one of the Ionian islands given to Greece by Britain on George’s accession to the throne, and where the municipality had presented the new king with a villa, Mon Repos, on a promontory just to the south of Corfu Town. But most of their time away from Athens was spent at Tato?, Andrea’s birthplace, the royal estate of 40,000 acres in the pine-scented foothills of Mount Parnеs, high enough to be much cooler than the capital. After buying Tato? in 1871, King George had established a vineyard to produce an alternative to the pine-infused retsina, which he detested, and a butter-making dairy farm with a range of Danish-style stone buildings. For those who were not well disposed towards their imported monarch there was evidence at Tato? that he had not embraced his adopted country quite as wholeheartedly as he liked to make out.

By 1886, the king had replaced the original small villa with a replica of a hideous Victorian-style house that stood in the grounds of his wife’s family home, Pavlovsk, and so Tato? became the one place where Queen Olga never felt homesick; she celebrated her birthday there each year with a big party for all the estate workers. The family all grew to love Tato? and most of them, including Andrea, are buried in the wooded cemetery there. But their white marble graves are seldom visited nowadays. Since 1967, when the last Greek king, Constantine II, went into exile in Surrey, the estate has become overgrown and the buildings are now mostly ruins. A few picnic tables scattered about the park hint at the symbolic gesture of giving Tato? to the republican Greek people of today, but few visitors come here now and if you ask for directions from Athens, you are almost guaranteed to get a blank look.

Andrea’s childhood was on the whole steady, but there were also events of great sadness. The first of these occurred when he was nine, when his sister Alexandra died while giving birth to her son, Dimitri, three years after her marriage to Grand Duke Paul of Russia. The whole family, including Andrea, travelled to Moscow, where the young Grand Duchess lay in state in a special room at the station, and then on to St Petersburg for the funeral. One of Andrea’s elder brothers later recalled that it was ‘all so unexpected and awful that the shock and sorrow overpowered us all’.

King George, who doted on his daughter, never got over it.

For all the king’s personal popularity, Greece remained a turbulent and violent country, and he survived several assassination attempts. In 1898, while out driving with his daughter Marie – later Grand Duchess George of Russia – his carriage was attacked by two men who opened fire with rifles at close range. Marie had a red bow in her hat which her father thought would make her an easy target for them ‘so he quickly stood up,’ she recalled, ‘put his hand on my neck and forced me down. With his other hand he menaced them with his walking stick.’ Both horses were hit and slightly wounded and a footman was injured in the leg; however the king and his daughter were miraculously unscathed.

When he was fourteen, Andrea began attending classes twice a week at the military college at Athens, where he was drilled by German officers and became quite friendly with the future dictator Theodore Pangalos,

an association that may later have saved his life. From the age of seventeen, he was privately tutored by another future revolutionary, Major Panayotis Danglis, who privately noted that his new charge was tall, quick and intelligent – and short-sighted.

The king was forever urging Danglis to increase Andrea’s hours of tuition, and when the family went on holiday to Corfu in the spring of 1900 Andrea was made to stay in and attend to his military studies rather than go on many of the picnics and excursions.

In 1902, aged twenty, Andrea was examined by a panel that included his father, his elder brothers, the prime minister, the archbishop, the war minister and half the teaching staff of the military academy. The king had been keen to ensure that the test was as rigorous as it could be, but they were unanimous in passing Andrea and he was duly commissioned as a subaltern in the cavalry. Shortly after this he met the beautiful seventeen-year-old Princess Alice of Battenberg, the girl who was to become his wife.

TWO

House of Battenberg

The House of Battenberg to which Alice belonged was slightly older than the House of Greece and equally romantic in its origins. Alice’s grandfather was Prince Alexander of Hesse, officially the third son of the famously ugly Grand Duke Louis II of Hesse and by Rhine but widely assumed to have been sired by the Grand Duchess’s handsome chamberlain, Baron Augustus Senarclens von Grancy, with whom the duchess had been openly living for three years by the time Alexander was born in 1823.

Alexander’s younger sister Marie, who was thought to have the same biological father, went on to marry the future Tsar Alexander II. Hence, at the age of eighteen, Alexander joined the tsar’s imperial army as a colonel, and was later promoted to major general when his sister produced an heir. However, his career faltered after he fell in love with Marie’s Polish lady-in-waiting, Julie Hauke, who, although a countess, was deemed to be unacceptably beneath his rank.

Julie became pregnant and Alexander married her, with the result that he was banished from Russia. His Hessian family was equally dismayed by the match but his brother, Louis III, nevertheless revived the dormant title of Battenberg – a small town in the north of the Grand Duchy – for Julie, with the quality of countess, later raised to princess. Alexander remained a prince but it was stressed that no child of their morganatic marriage would have a claim to the Hessian throne.

Their eldest son was Alice’s father, Prince Louis of Battenberg. From an early age Louis was determined to depart from the Hessian soldiering tradition and become a sailor, but there were only a handful of vessels in the German fleet at that time, so in 1868, aged fourteen, he set out for England to join the Royal Navy. Considering that he never entirely lost his German accent he had a remarkably successful career, culminating in his appointment as First Sea Lord, the pinnacle of his profession, in 1912. Tall and handsome, with dark, hooded eyes, Louis was also a good dancer and an entertaining raconteur, and as a young midshipman he had wooed a succession of pretty girls in the ports where his ship put in. His dalliances did not always require much effort. As an orderly officer in the suite of his cousin, the Prince of Wales, on his tour of India in 1875, he recalled one evening when after dinner each member of the prince’s entourage was guided to his own private ‘enormous divan with many soft cushions. Refreshments and smoking material were laid out on a little table. On the divan reclined a native girl in transparent white garments.’ On another occasion, when the Maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir arranged for a well-born girl to be placed in the Prince of Wales’s tent, Louis contrived to transfer her to his own.

A few years later, while serving as an officer of the royal yacht Osborne, Louis fell in love with the Prince of Wales’s mistress, Lillie Langtry, the beautiful Jersey-born actress. When she became pregnant, there were at least two other possible candidates for the child’s paternity, but Louis believed that he was the father and gallantly told his parents that he intended to stand by Lillie.

His parents were anxious to avoid a scandal, however, and promptly arranged a financial settlement for her. Queen Victoria then fixed it for Louis to be posted to the frigate Inconstant, which was to undertake a voyage round the world under sail, ‘a project designed to keep him out of harm’s way for a long time’.

Soon after his return he set his romantic sights on his young first cousin once removed from the main branch of the Hessian royal family, whom he married in 1884. His bride was twenty-year-old Princess Victoria, who had been born in 1863 at Windsor Castle, the eldest of seven children of Grand Duke Louis IV of Hesse and Princess Alice, Queen Victoria’s second daughter. Princess Victoria had experienced profound sadness during her short life, losing her younger brother, Fritz, when he fell out of a window at the age of ten, and as a teenager unwittingly initiating an even greater family tragedy. In the winter of 1878, aged fifteen, she had fallen ill with diphtheria, but before the symptoms of her illness became apparent she had read aloud parts of Alice in Wonderland to her five younger siblings.

All but one of them had caught the disease, as had her father, the Grand Duke. Her mother, Alice, had insisted on nursing them all and, though urgently warned not to do so by her doctors, had hugged and kissed her son while telling him that his little sister May had died. A month later Alice, too, succumbed to the disease. She was thirty-five.

After their mother’s death, young Victoria had taken charge of running the household and looking after her four surviving siblings – Ella, Irene, Ernie and Alix – supported from afar by her grandmother, Queen Victoria, who urged her to ‘look upon me as a mother’.

By the time she fell in love with Louis, she was still only nineteen, he twenty-eight, tall, dashing and sun-tanned from his travels – ‘a fairy-tale prince’ according to at least one biographer.

In some ways they seemed ill-suited. Despite his undoubted qualities, Louis was rather flashy, and loved dressing up in uniforms – he also boasted a large tattoo of a dragon stretching from his chest and to his legs.

Victoria was on the whole more self-effacing and was slightly embarrassed by Louis’ sartorial flamboyance. She was also more of a free spirit, as well as being highly intelligent. ‘Radical in her ideas,’ wrote Philip Ziegler, ‘insatiably curious, argumentative to the point of perversity, she leavened the somewhat doctrinaire formality of Prince Louis.’

Despite their differences, it proved to be an extremely successful marriage and produced four remarkable children.

Philip’s mother, Alice, was the eldest of these, ‘a fine sturdy baby’

born in 1885, at Windsor Castle, like her mother, in the presence of Queen Victoria, who from time to time helped the family out financially and did what she could to advance Louis’ naval career.

Alice was a handsome child, tall and slender with golden hair and large brown eyes.

However, she was slow in learning to talk and often had a strange faraway look,

which her mother at first mistook for absentmindedness. It was not until she was four that an aurist pronounced her almost completely deaf due to a thickening of the Eustachian tubes, which at that time was deemed inoperable although nowadays it would be curable.

Her condition, which improved very slightly as she grew older, made her unusually self-reliant, able to spend hours happily absorbed in her own company. Her mother was adamant that she should not draw attention to her disability and she was thus forbidden from asking anyone to repeat what they had said.

Required to disguise her confusion as best she could, she soon became a brilliant lip-reader and, because the family moved about so much, following Louis’ postings in Britain and Malta and summer holidays at the various Hessian schlosses, she learned to do so in several languages. Acquaintances often failed to notice any defect, as her mother would have wished, and so striking were her beauty, poise and accomplishments that the Prince of Wales reputedly remarked that ‘no throne is too good for her’.

In June 1902, she went to stay at Buckingham Palace for the coronation of King Edward VII, and met Andrea, Queen Alexandra’s nephew, who appeared to her to be ‘exactly like a Greek God’, so she later told her grandson Prince Charles.

The coronation was delayed at the last minute when the king fell ill with appendicitis, but there was still time before the various guests dispersed for Andrea and Alice to fall in love and become privately engaged. Alice’s mother Victoria later admitted that to begin with she was not in favour of this arrangement, thinking them too young.

It was also said – though she did not admit this – that she thought her daughter could do better than the fourth son of the insecure and impecunious King of Greece.

In July Alice and her mother returned home to Heiligenberg, from where she wrote to Andrea every day. On one occasion, when a week had gone by without a letter from him, a friend found her in tears, tormented by the thought that something must have happened to him or that he had changed his mind. The next morning she arrived at school glowing, having just received five letters in the post from Greece.

After an emergency operation to remove his appendix, Edward VII was well enough to be crowned in early August and Andrea and Alice returned to Buckingham Palace and travelled in the same carriage to Westminster Abbey, together with Alice’s mother and Andrea’s elder brother, George. After the coronation there was a further separation while Andrea was away on military duty in Greece, but in May 1903 he returned, Edward VII gave his consent and their engagement became official. The announcement came as a shock to some of the snootier European royalty, the octogenarian Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz bemoaning ‘the very youthful betrothal, so odd, no money besides!’ She even questioned the attendance of Andrea’s aunt, Queen Alexandra, at the wedding: ‘Why? There is surely no reason for it, a Battenberg, daughter of an illegitimate father, he a fourth son of a newly baked King!’

Still, the wedding at Darmstadt in October was a spectacular event and drew an impressive array of European royalty. Among those present was Tsar Nicholas II – Andrea’s first cousin, son of his aunt Dagmar, and husband of Alice’s aunt Alix – who gave the couple a Wolseley motor car and threw a bag of rice in Alice’s face as the couple drove away in it.

Three hundred and fifty Russian detectives patrolled the town to ensure the tsar’s safety.

There were two religious ceremonies, Protestant and Russian Orthodox, the first preceded by a thirty-strong royal procession into the chapel, followed by Andrea and his parents, and lastly Alice with hers. During the nervous exchange of vows, Alice was defeated by the bushiness of the priest’s beard and failed to lip-read the questions, so when asked whether she consented freely to marriage she replied ‘No’, and when asked whether she had promised her hand to someone else she said ‘Yes’.

They began their married life in a wing of the royal palace in Athens, spending summers at Tato? or with her parents in England, Malta and Germany. Their first child, Margarita, was born in 1905, and that autumn they all moved to Larissa, a garrison town in Thessaly on the Turkish border, where Andrea was responsible for transforming mountain goatherds into cavalrymen.

Shortly after their return to Athens the following spring, their second daughter, Theodora, known in the family as Dolla, was born.

In 1907 the Greek royal family came under attack in the local press due to inflated estimates of the king’s wealth and a rumour that the princes were to receive annuities. ‘To be remunerated for doing nothing is the privilege of the Russian Grand Dukes,’ snarled one newspaper. In another the princes were accused of failing to take the lead in times of trouble, and of ‘loafing about the boulevards of Paris’ while Salonika was set ablaze by Bulgarians in 1902.

The British ambassador Sir Francis Elliot considered the charge of indifference undeserved and the criticisms ‘characteristic of this country where liberty is confounded with license, and disrespect for authority mistaken for independence’.

The rumblings continued, though, and in August 1909 disgruntled officers launched a coup d’еtat, with the aim of installing the charismatic Cretan nationalist Eleftherios Venizelos as prime minister and preventing the sons of the king from holding any high commands in the army. Andrea had by then completed his staff college exams but, for their father’s sake, he and his four brothers resigned their posts, leading to three years of demoralizing unemployment.

In 1912, though, he was able to resume his military career when Greece entered the First Balkan War against Turkey, with the aim of expanding Greek territory towards Constantinople and resolving the ownership of Crete. Andrea and his brothers made for Larissa to join the conquering army led by their eldest brother, Crown Prince Constantine, which then swept victoriously through southern and western Macedonia, repeatedly putting the Turks to rout. The campaign not only helped revive the popularity of the Greek princes but also provided Alice with the opportunity for what her biographer Hugo Vickers calls ‘her finest hour’.