По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

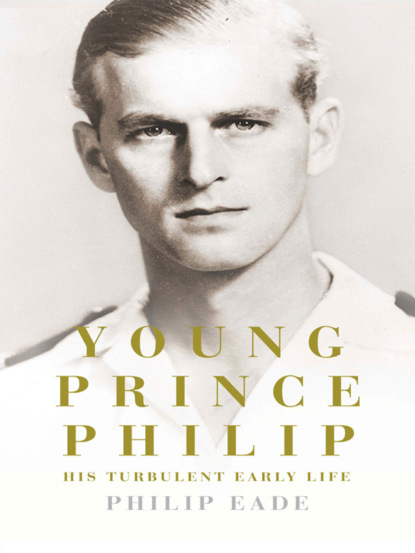

Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Andrea was never comfortable about receiving handouts, but he was at least fortunate in having several close relations with considerable sums to spare. After Christopher’s wife Nancy died in 1923, the money she left took care of the children’s school fees and other items that Andrea could not afford.

Then there was Dickie Mountbatten’s new wife Edwina, who had inherited almost half of her grandfather Ernest Cassel’s estate, conservatively estimated at ?6 million, and could thus be justly described as ‘The Richest Girl in Britain’.

Edwina found subtle ways of helping without offending Andrea’s pride – when ordering clothes, she stipulated extra wide hems so that they could be later handed down to her nieces and adjusted if need be

– and in 1924 she also took out an insurance policy for her nephew Philip.

According to his cousin Alexandra, as he grew up Philip was himself ‘trained to save and economise better than other children, so much so that he even acquired a reputation for being mean’.

Alexandra – whose version of events was later disputed by Philip – was the originator of the Dickensian legends portraying the boy in patched clothes, making do with no toys and forlornly staying behind after school on wet days because he had no raincoat.

Neither Alice nor Andrea had paid jobs in Paris. Alice volunteered in a charity boutique in the Faubourg St Honorе, called Hellas, selling traditional Greek tapestries, medallions and honey, with the proceeds going towards helping her fellow less fortunate Greek refugees. The shop did quite well, not least because its customers appreciated the novelty of being served by a princess.

Andrea tended to become restless and depressed when he had nothing to do, but, as an еmigrе Greek prince experienced only in soldiering, he was not especially employable in Paris. Instead he devoted much of his time to writing a personal account of the Greek debacle in Turkey, Towards Disaster, which was eventually published in 1930, translated into English from his original Greek manuscript by Alice. Designed to justify his actions at the battle of Sakaria and thereby redeem his reputation, the book’s indignant tone served more effectively to show how embittered he remained almost a decade after the events in question.

Otherwise, he took the children for long walks in the Bois de Boulogne or motored into the centre of the city to meet fellow exiles and hear about the latest depressing developments in Athens.

The death of Andrea’s brother King Constantine had done little to quell anti-royalist feeling in Greece and in December 1923 Colonel Plastiras succeeded in persuading the cabinet that the continuance of the Gl?cksburg dynasty was ‘a national stigma which should be blotted out’. King George II and his queen, Elizabeth, were thus required to leave the country in a steamer bound for Romania.

In February 1924, in the national assembly General Pangalos launched a scathing attack on Andrea, reiterating his responsibility for the defeat at Sakaria and saying he would have been executed but for the intervention of a ‘semi-official British envoy’ (i.e. Talbot) who had come to Greece with a ‘sackful of promises’.

On 25 March the revolutionary constituent assembly issued a resolution proclaiming Greece a republic, forbidding the Gl?cksburgs ‘their sojourn in Greece’ and authorizing the ‘forcible expropriation’ of all property belonging to the deposed dynasty.

Any hope that Andrea and Alice might be able to return home was effectively extinguished at this point.

Unable to return to Greece, they put down more permanent roots at St Cloud, where another of Andrea’s brothers, Nicholas, and his wife Ellen and their three daughters were also now living, as was Margarethe ‘Meg’ Bourbon, daughter of George and Andrea’s uncle Waldemar, and her family. On Sundays Big George and Marie would often hold family lunch parties together but otherwise Marie tended to live with her father in the centre of Paris while pursuing her career as a psychoanalyst. Left on his own next door, Big George would come over each evening, we are told, to say his prayers with Philip and kiss him goodnight.

Many of the earliest recorded glimpses we have of Philip are on holiday. In the summer of 1923, at Arcachon, on the coast south-west of Bordeaux, his aunt Louise found the two-year-old to be ‘quite too adorable for words, a perfect pet, so grown up & speaks quite a lot & uses grand phrases. He is the sturdiest little boy I have ever seen & I can’t say he is spoilt.’

In the autumn of 1924, aged three and a half, he made his third trip to London, but the first one about which he could later remember anything. He was taken by train and boat from Paris by his nurse, and was met by Alice, who had gone on ahead to visit her mother, at Victoria Station. Philip was ‘very pleased and excited’, Alice recorded, and ‘discovered the first policeman by himself & pointed him out to me. Also the buses were his joy, & I had to take him in one this afternoon. Of course he made straight for the top, but it was too windy and showery to go there, but he was reasonable and went inside …’

Philip was about four when he and two of his sisters and Miss Roose first went to stay with the Foufounis family, staunch Greek royalists and fellow еmigrеs from the revolution, who had a farm just outside Marseilles. Philip became great friends with the children, Ria, Ianni and Hеl?ne, and was treated as part of the family. Their newly widowed mother doted on him to such an extent that Hеl?ne recalled becoming ‘terrified she would switch her affections completely from me to him … the little blue-eyed boy with the most fascinating blond-white hair seemed to have everything I lacked. In my mind he became a great danger, and I became ridiculously jealous.’

For her own part, Madame Foufounis later recalled: ‘He [Philip] was with us so often people used to ask, “Are you his guardian or his governess?” I was neither, yet much more. I loved Philip as my own.’

Philip also spent summer holidays with the Foufounises at Berck Plage near Le Touquet in the Pas-de-Calais, where he and his sisters would go to stay for up to three months at a time. The eldest Foufounis girl, Ria, was in plaster up to her hips for four years as a result of a bad fall, and Hеl?ne later described how Philip would sit for long periods next to her bed talking to her, refusing to be lured away by the other children. One day a spectacularly insensitive guest bought some toys for all the children except Ria, explaining to her that ‘you can’t play like the others’. The others were stunned by this, none more so than four-year-old Philip, whose eyes ‘grew wider and bluer. He looked at Ria, who was trying very hard not to cry, then he ran out of the room and returned ten minutes later with his arms full of his own battered toys, and his new one, and he put them all on Ria’s bed saying, “All this is yours!”’

In other respects Philip was a boisterous, mischievous boy. Each day after lunch, he and Ianni would take Persian rugs from the drawing room through the French windows and lay them out in the garden for their siestas. One afternoon the boys disappeared with the rugs and after an hour’s search they were found walking from door to door down the road with the carpets on their shoulders, emulating the Arab salesmen they had seen selling oriental wares on the beach.

Their various misdeeds earned them regular spankings from the Foufounises’ governess, a fierce – and, incidentally, kleptomaniac – Scottish woman called Miss Macdonald although known to the children as Aunty. Hеl?ne described how on one occasion after Ianni and Philip had broken a large vase, Ianni received his usual beating, whereas Philip vanished. Hеl?ne eventually spotted his frightened blue eyes behind a French window and heard him call out to Miss Roose: ‘Nanny, let’s clear.’ When Aunty heard this, too, she rushed towards Philip, who ‘straightened himself, looked her squarely in the eye, and said: “I’ll get my spanking from Roosie, thank you”.’ And he did.

Other holidays were spent at Panker, the Landgrave of Hesse’s summer house on the Baltic coast, with Philip’s Prussian aunt, Sophie, Constantine’s widow, and a collection of royal cousins, including the deceased King Alexander’s young daughter Alexandra, whose first memory of Philip was as

a tiny boy with his shrimping net, running eagerly, far ahead of me, over a white expanse of sand towards the sea, [then] splashing merrily in the water, refusing to leave it, running and eluding every attempt to capture him. Long after I have returned to my nannie and the waiting towel, Philip is still there until he is finally caught and dragged out forcibly, blue with cold, yelling protests through chattering teeth.

Like the Foufounises at Villa Georges, they kept pigs at Panker, and Philip loved feeding them, although he later professed to have ‘absolutely no recollection’ of an occasion recounted by Alexandra in which he was said to have released the pigs from their sties and herded them up to the lawn where they created havoc with the adults’ tea.

About an hour away from Panker, his great-aunt Irene (Victoria’s sister) and her husband Prince Henry had their country property, Hemmelmark, where Philip jumped off a hay wagon and broke a front tooth. ‘Of course he was a great show-off,’ his sisters Margarita and Sophie recalled. ‘He would always stand on his head when visitors came.’

By their account, as he grew older, he also became ‘very pugnacious and the other children were scared to death of him’.

Philip and his sisters also went to stay with their cousin, Queen Helen of Romania (daughter of their uncle King Constantine of Greece and deserted wife of King Carol), and her son Michael, at the dilapidated Cotroceni Palace near Bucharest, repairing in the heat of high summer either to their castle at Sinaia high up in the Carpathian Mountains or to the newly built Mamaia Palace at the mouth of the Danube on the Black Sea, which had quickly become the centre of a thriving resort, where Philip first experienced pony riding on the beach. Michael, a more taciturn child, was a few months younger. In 1927, at the age of five, on the death of his grandfather Ferdinand, he was proclaimed King of Romania under a regency. When he asked his mother the next day why people were calling him ‘Your Majesty’, she thought it best to tell him, ‘It’s just another nickname, dear.’

Philip and his two elder sisters, Theodora and Margarita, stayed at Mamaia the next year

but Michael’s new status seemed to make no difference to the children’s play ‘except that there were always many more people about’, wrote Alexandra, and the three of them never quite seemed able to wander off by themselves. Michael, though, ‘fully realised he was King and early adopted courtly little ways’, once telling Alexandra’s mother: ‘I am most pleased with Sandra. She suits me very well.’

The anecdotal evidence gives the impression that Philip saw little of his own parents in the course of his nomadic wanderings as a small child. While Victoria Milford Haven’s biographer asserts that Alice often travelled about with him and enjoyed ‘showing him things and watching his alert intelligence growing’,

her nerves had been badly strained by all the anxieties surrounding the family’s exile from Greece, and because of this the children were regularly packed off to friends and relations for long stints without their parents, while the family home at St Cloud was shut up. ‘Philip goes to Adsdean [Dickie and Edwina’s country home],’ wrote Victoria to her friend Nona Kerr in June 1926, ‘where they can keep him until autumn if desired, only for Goodwood week his room will be needed for guests, so if you [Nona] still would like & could have him & Roose that would be the time for his visit to you.’

Philip went regularly to Nona Kerr over the years and he took to calling her ‘Mrs Good … because she is good and that is the right name’.

There are several indications that from an early stage in their new life in Paris, all was not well between Alice and Andrea. Prominent among them is the story of Alice’s infatuation with an unnamed, married Englishman, whom she fell in love with in 1925 when she was forty and Philip four. According to the account given to Alice’s doctor by her lady-in-waiting, it never amounted to an actual affair, and Alice eventually gave up, consoling herself that they would ‘meet again in another world’. Her biographer suggests that in any case Alice’s strictly conventional background and ‘high moral principles’ would have prevented anything improper from happening, pointing out that ‘nothing in her life was flighty or flippant’.

However, the mere fact of this infatuation suggests that she and Andrea had already begun to grow apart.

In 1927, aged six, Philip started at a progressive American kindergarten housed in Jules Verne’s former home – a rambling old St Cloud mansion (also since demolished) at 7 Avenue Eugenie just above the Seine, opposite the western end of the Bois de Boulogne, and shaded by the large trees which gave the school its name, the Elms.

His uncle Christopher paid the fees.

The accounts we have of Philip’s time at the school all emerged after his engagement to Princess Elizabeth and thus they may have been embroidered with the benefit of hindsight. One of his teachers, though, remembered being struck by the young prince’s precocious sense of responsibility.

Having walked to school with his nanny, she recalled, he usually arrived there half an hour early, and he would fill in the time cleaning blackboards, filling inkwells, straightening the classroom furniture, picking up waste paper and watering the plants. Another tale was later told how, on his first day, some of the other boys had demanded that Philip ‘fight it out’ with another new boy. After a brief scuffle, he whispered to his opponent, ‘Are you having fun?’ When the other boy admitted he wasn’t, Philip said ‘Let’s quit’, which they did.

By all accounts, he settled in quickly, although he was teased for having no last name. Asked to introduce himself in class he insisted at first that he was ‘just Philip’, before eventually awkwardly admitting that he was ‘Philip of Greece’.

The school’s founder and headmaster, a thirty-one-year-old native of New England, Donald MacJannet, known to the boys as ‘Mr Mac’, later recalled the young prince as exuberant and sometimes rowdy yet at the same time polite and disciplined: he regularly repeated the mantra learned from his elder sisters: ‘You shouldn’t slam doors or shout loud’. He ‘wanted to learn to do everything’, including waiting at table,

his mother having taught him that ‘a gentleman does not allow a woman to wait on him’.

He also appeared to take for granted his mother’s insistence on hard work: Alice made him do extra Greek prep three evenings a week, and asked the school to set him a daily exercise for the holidays.

When Philip first arrived at the Elms, Alice had told the headmaster that her son had ‘plenty of originality and spontaneity’ and suggested that he be encouraged to work off his energy playing games and learning ‘Anglo-Saxon ideas of courage, fair play and resistance’. She said she envisaged him ending up in an English-speaking country, perhaps America, so she wanted him to learn good English. Philip later recalled that at that time ‘We spoke English at home … but then the conversation would go into French. Then it went into German on occasion … If you couldn’t think of a word in one language, you tended to go off in another.’ Alice also wanted him to ‘develop English characteristics’, although she was thwarted in this for the time being.

For one thing, Philip’s two best friends at the school were Chinese – Wellington and Freeman Koo, sons of the prominent diplomat V. K. Wellington Koo, then ambassador to Paris, later foreign secretary, acting premier, interim president of China and ultimately judge at the International Court at The Hague. Their mother, Hui-Lan Koo, was one of the forty-two acknowledged children of the sugar king Oei Tiong Ham and much admired in 1920s Parisian society for her adaptations of traditional Manchu fashion, which she wore with lace trousers and jade necklaces.

The two Koo boys had each been robustly introduced to Philip at the Elms as ‘Ching Ching Chinaman’

but they proved well up to looking after themselves, and their knowledge of jiu-jitsu came in useful whenever Philip found himself outnumbered in playground tussles. He often spent the weekend at the Koos’ residence in Paris, where, invariably spurred on by Philip, the boys all ran steeplechases and played other raucous games amid the Chinese embassy’s precious artefacts. The ambassador’s wife admitted to Alice that however much they enjoyed having her son to stay, they were always a little relieved when the time came for him to go and nothing had been broken.

Other friends at the Elms during his time included his Franco-Danish cousins Jacques and Anne Bourbon, who later married King Michael of Romania. But the majority of his classmates were American and Philip picked up something of their drawl and learned to play baseball before he played cricket. He coveted anything that came from the New York department store Macy’s and was only too pleased to swap a gold bibelot given to him by George V for a state-of-the-art three-colour pencil belonging to another boy.

FIVE

Orphan Child

However much Philip enjoyed his first school, his restless energy still made him a handful for his parents when he came home each afternoon. Another option would have been for him to board at the Elms, but Alice told him they could not afford the fees.