По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

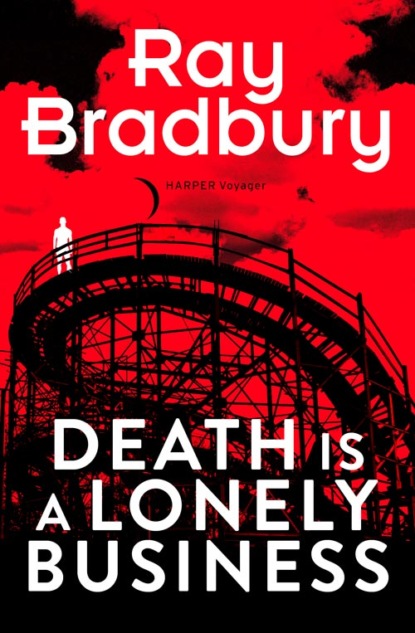

Death is a Lonely Business

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For some forty days it doesn’t come out at all.

The rest of the time, if you’re lucky, the sun rises, as it does for the rest of Los Angeles and California, at five-thirty or six in the morning and stays all day.

It’s the forty- or sixty-day cycles that drip in the soul and make the riflemen clean their guns. Old ladies buy rat poison on the twelfth day of no sun. But on the thirteenth day, when they are about to arsenic their morning tea, the sun rises wondering what everyone is so upset about, and the old ladies feed the rats down by the canal, and lean back to their brandy.

During the forty-day cycles, the foghorn lost somewhere out in the bay sounds over and over again, and never stops, until you feel the people in the local graveyard beginning to stir. Or, late at night, when the foghorn gets going, some variety of amphibious beast rises in your id and swims toward land. It is swimming somewhere yearning, maybe only for sun. All the smart animals have gone south. You are left stranded on a cold dune with an empty typewriter, an abandoned bank account, and a half-warm bed. You expect the submersible beast to rise some night while you sleep. To get rid of him you get up at three a.m. and write a story about him, but don’t send it out to any magazines for years because you are afraid. Not Death, but Rejection in Venice is what Thomas Mann should have written about.

All this being true, or imagined, the wise man lives as far inland as possible. The Venice police jurisdiction ends as does the fog at about Lincoln Avenue.

There, at the very rim of official and bad weather territory, was a garden I had seen only once or twice.

If there was a house in the garden it was not visible. It was so surrounded by bushes, trees, tropical shrubs, palm fronds, bulrushes, and papyrus that you had to cut your way in with a reaper. There was no sidewalk, only a beaten path. A bungalow was in there, all right, sinking into a chin-high field of uncut grass, but so far away from the street it looked like an elephant foundering in a tar pit, soon to be gone forever. There was no mailbox out front. The mailman must have just tossed the mail in and beat it before something sprang out of the jungle to get him.

From this green place came the smell of oranges and apricots in season. And what wasn’t orange or apricot was cactus or epiphyllum or night-blooming jasmine. No lawnmower ever sounded here. No scythe ever whispered. No fog ever came. On the boundary of Venice’s damp eternal twilight, the bungalow survived amid lemons that glowed like Christmas tree lights all winter long.

And on occasion, walking by, you thought you heard okapi rushing and thumping a Serengeti Plain in there, or great sunset clouds of flamingos startled up and wheeling in pure fire.

And in that place, wise about the weather, and dedicated to the preservation of his eternally sunburned soul, lived a man some forty-four years old, with a balding head and a raspy voice, whose business, when he moved toward the sea and breathed the fog, was bruised customs, broken laws, and the occasional death that could be murder.

Elmo Crumley.

And I found him and his house because a series of people had listened to my queries, nodded, and pointed directions.

Everyone agreed that every late afternoon, the short detective ambled into that green jungle territory and disappeared amid the sounds of hippos rising and flamingos in descent.

What should I do? I thought. Stand on the edge of his wild country and shout his name?

But Crumley shouted first.

“Jesus Christ, is that you?”

He was coming out of his jungle compound and trekking along the weedpath, just as I arrived at his front gate.

“It’s me.”

As the detective trailblazed his own uncut path, I thought I heard the sounds I had always imagined as I passed: Thompson’s gazelles on the leap, crossword-puzzle zebras panicked just beyond me, plus a smell of golden pee on the wind—lions.

“Seems to me,” groused Crumley, “we played this scene yesterday. You come to apologize? You got stuff to say that’s louder and funnier?”

“If you’d stop moving and listen,” I said.

“Your voice carries, I’ll say that. Lady I know, three blocks from where you found the body, said because of your yell that night, her cats still haven’t come home. Okay, I’m standing here. And?”

With every one of his words, my fists had jammed deeper into my sports jacket pockets. Somehow, I couldn’t pull them out. Head ducked, eyes averted, I tried to get my breath.

Crumley glanced at his wristwatch.

“There was a man behind me on the train that night,” I cried, suddenly. “He was the one stuffed the old gentleman in the lion cage.”

“Keep your voice down. How do you know?”

My fists worked in my pockets squeezing. “I could feel his hands stretched out behind me. I could feel his fingers working, pleading. He wanted me to turn and see him! Don’t all killers want to be found out?”

“That’s what dime-store psychologists say. Why didn’t you look at him?”

“You don’t make eye contact with drunks. They come sit and breathe on you.”

“Right.” Crumley allowed himself a touch of curiosity. He took out a tobacco pouch and paper and started rolling a cigarette, deliberately not looking at me. “And?”

“You should’ve heard his voice. You’d believe if you’d heard. My God, it was like Hamlet’s father’s ghost, from the bottom of the grave, crying out, remember me! But more than that—see me, know me, arrest me!”

Crumley lit his cigarette and peered at me through the smoke.

“His voice aged me ten years in a few seconds,” I said. “I’ve never been so sure of my feelings in my life!”

“Everybody in the world has feelings.” Crumley examined his cigarette as if he couldn’t decide whether he liked it or not. “Everyone’s grandma writes Wheaties jingles and hums them until you want to kick the barley-malt out of the old crone. Songwriters, poets, amateur detectives, every damn fool thinks he’s all three. You know what you remind me of, son? That mob of idiots that swarmed after Alexander Pope waving their poems, novels, and essays, asking for advice, until Pope ran mad and wrote his ‘Essay on Criticism.’”

“You know Alexander Pope?”

Crumley gave an aggrieved sigh, tossed down his cigarette, stepped on it.

“You think all detectives are gumshoes with glue between their ears? Yeah, Pope, for Christ’s sake. I read him under the sheets late nights so my folks wouldn’t think I was queer. Now, get out of the way.”

“You mean all this is for nothing,” I cried. “You’re not going to try to save the old man?”

I blushed, hearing what I had said.

“I meant—”

“I know what you meant,” said Crumley, patiently.

He looked off along the street, as if he could see all the way to my apartment and the desk and the typewriter standing there.

“You’ve latched on to a good thing, or you think you have. So you run fevers. You want to get on that big red streetcar and ride back some night and catch that drunk and haul him in, but if you do, he won’t be there, or if he is, not the same guy, or you won’t know him. So right now, you’ve got bloody fingernails from beating your typewriter, and the stuffs coming good, as Hemingway says, and your intuition is growing long antennae that are ever so sensitive. That, and pigs’ knuckles, buys me no sauerkraut!”

He started off around the front of his car in a replay of yesterday’s disaster.

“Oh, no you don’t!” I yelled. “Not again. You know what you are? Jealous!”

Crumley’s head almost came off his shoulders. He whirled.

“I’m what?”

I almost saw his fingers reach for a gun that wasn’t there.

“And, and, and—” I floundered. “You—you’re never going to make it!”

My insolence staggered him. His head swiveled to stare at me over the top of his car.