По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

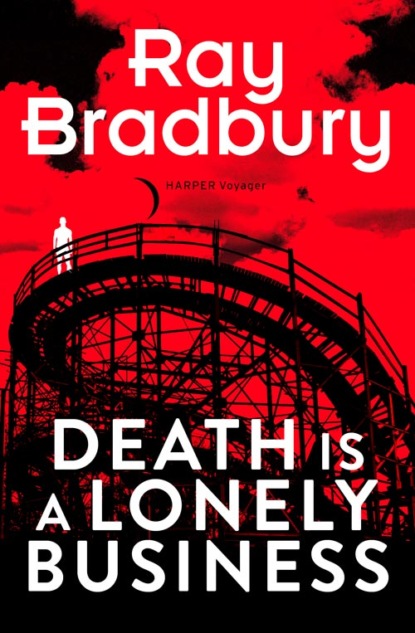

Death is a Lonely Business

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Fat chance.”

“Damn!”

I tore the page out of the machine.

Just then, my private phone rang.

It seemed it took me ten miles of running to get there, thinking, Peg!

All the women in my life have been librarians, teachers, writers, or booksellers. Peg was at least three of those, but she was far away now, and it terrified me.

She had been all summer in Mexico, finishing studies in Spanish literature, learning the language, traveling on trains with mean peons or buses with happy pigs, writing me love-scorched letters from Tamazunchale or bored ones from Acapulco where the sun was too bright and the gigolos not bright enough; not for her anyway, friend to Henry James and consultant to Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin. She carried a lunchbucket full of books everywhere. I often thought she ate the brothers Goncourt like high tea sandwiches in the late afternoons.

Peg.

Once a week she called from somewhere lost in the church-towns or big cities, just come up out of the mummy catacombs at Guanajuato or gasping after a climb down Teotihuacán, and we listened to each other’s heartbeats for three short minutes and said the same dumb things to each other over and over and over; the sort of litany that sounds fine no matter how long or often you say it.

Each week, when the call came, the sun blazed over the phone booth.

Each week, when the talk stopped, the sun died and the fog arose. I wanted to run pull the covers over my head. Instead, I punched my typewriter into bad poems, or wrote a tale about a Martian wife who, lovesick, dreams that an earthman drops from the sky to take her away, and gets shot for his trouble.

Peg.

Some weeks, as poor as I was, we pulled the old telephone tricks.

The operator, calling from Mexico City, would ask for me by name.

“Who?” I would say. “What was that again? Operator, speak up?”

I would hear Peg sigh, far away. The more I talked nonsense, the longer I was on the line.

“Just a moment, operator, let me get that again.”

The operator repeated my name.

“Wait—let me see if he’s here. Who’s calling?”

And Peg’s voice, swiftly, would respond from two thousand miles off. “Tell him it’s Peg! Peg.”

And I would pretend to go away and return.

“He’s not here. Call back in an hour.”

“An hour—” echoed Peg.

And click, buzz, hum, she was gone.

Peg.

I leaped into the booth and yanked the phone off the hook.

“Yes?” I yelled.

But it wasn’t Peg.

Silence.

“Who is this?” I said.

Silence. But someone was there, not two thousand miles away, but very near. And the reception was so clear, I could hear the air move in the nostrils and mouth of the quiet one at the other end.

“Well?” I said.

Silence. And the sound that waiting makes on a telephone line. Whoever it was had his mouth open, close to the receiver. Whisper. Whisper.

Jesus God, I thought, this can’t be a heavy-breather calling me in a phone booth. People don’t call phone booths! No one knows this is my private office.

Silence. Breath. Silence. Breath.

I swear that cool air whispered from the receiver and froze my ear.

“No, thanks,” I said.

And hung up.

I was halfway across the street, jogging with my eyes shut, when I heard the phone ring again.

I stood in the middle of the street, staring back at the phone, afraid to go touch it, afraid of the breathing.

But the longer I stood there in danger of being run down, the more the phone sounded like a funeral phone calling from a burial ground with bad telegram news. I had to go pick up the receiver.

“She’s still alive,” said a voice.

“Peg?” I yelled.

“Take it easy,” said Elmo Crumley.

I fell against the side of the booth, fighting for breath, relieved but angry.

“Did you call a moment ago?” I gasped. “How’d you know this number?”

“Everyone in the whole goddamn town’s heard that phone ring and seen you jumping for it.”

“Who’s alive?”

“The canary lady,. Checked her late last night—”

“That was last night.”