По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

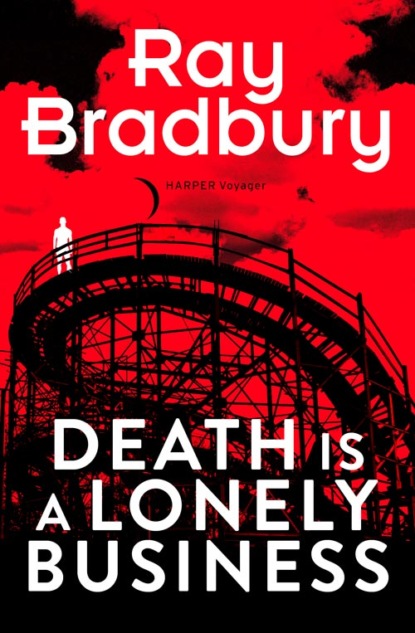

Death is a Lonely Business

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Make what?” he said.

“Whatever it is you want to do, you—won’t—do—it.”

I jolted to a full stop, astounded. I couldn’t remember ever having yelled like this at anyone. In school, I had been the prize custard. Every time some teacher slammed her jaws, my crust fell. But now—

“Unless you learn,” I said, lamely, feeling my face fill up with hot color, “to—ah—listen to your stomach and not your head.”

“Norman Rockwell’s Philosophical Advice for Wayward Sleuths.” Crumley leaned against his car as if it were the only thing in the world that held him up. A laugh burst from his mouth, which he capped with his palm, and he said, muffled, “Continue.”

“You don’t want to hear.”

“Kid, I haven’t had a laugh in days.”

My mouth gummed itself shut. I closed my eyes.

“Go on,” said Crumley, with a gentler tone.

“It’s just,” I said, slowly, “I learned years ago that the harder I thought, the worse my work got. Everyone thinks you have to go around thinking all the time. No, I go around feeling and put it down and feel again and write that down and, at the end of the day, think about it. Thinking comes later.”

There was a curious light in Crumley’s face. He tilted his head now this way to look at me, and then tilted it the other way, like a monkey in the zoo staring out through the bars and wondering what the hell that beast is there outside.

Then, without a word, or another laugh or smile, he simply slid into the front seat of his car, calmly turned on the ignition, softly pressed the gas, and slowly, slowly drove away.

About twenty yards down the line, he braked the car, thought for a moment, backed up, and leaned over to look at me and yelled:

“Jesus H. Christ! Proof! God damn it. Proof.”

Which made me yank my right hand out of my jacket pocket so fast it almost tore the cloth.

I held my fist out at last and opened my trembling fingers.

“There!” I said. “You know what that is? No. Do I know what it is? Yes. Do I know who the old man is? Yes. Do you know his name? No!”

Crumley put his head down on his crossed arms on the steering wheel. He sighed. “Okay, let’s have it.”

“These,” I said, staring at the junk in my palm, “are little A’s and small B’s and tiny C’s. Alphabets, letters, punched out of trolley paper transfers. Because you drive a car, you haven’t seen any of this stuff for years. Because all I do, since I got off my rollerskates, is walk or take trains, I’m up to my armpits in these punchouts!”

Crumley lifted his head, slowly, not wanting to seem curious or eager.

I said, “This one old man, down at the trolley station, was always cramming his pockets with these. He’d throw this confetti on folks on New Year’s Eve, or sometimes in July and yell Happy Fourth! When I saw you turn that poor old guy’s pockets inside out I knew it had to be him. Now what do you say?”

There was a long silence.

“Shit.” Crumley seemed to be praying to himself, his eyes shut, as mine had been only a minute ago. “God help me. Get in”

“What?”

“Get in, God damn it. You’re going to prove what you just said. You think I’m an idiot?”

“Yes. I mean—no.” I yanked the door open, struggling with my left fist in my left pocket. “I got this other stuff, seaweed, left by my door last night and—”

“Shut up and handle the map.”

The car leaped forward.

I jumped in just in time to enjoy whiplash.

Elmo Crumley and I stepped into the tobacco smells of an eternally attic day.

Crumley stared at the empty space between the old men who leaned like dry wicker chairs against each other.

Crumley moved forward to hold out his hand and show them the dry-caked alphabet confetti.

The old men had had two days now to think about the empty seat between them.

“Son-of-a-bitch,” one of them whispered.

“If a cop,” murmured one of them, blinking at the mulch in his palm, “shows me something like that, it’s gotta come from Willy’s pockets. You want me to come identify Turn?”

The other two old men leaned away from this one who spoke, as if he had said something unclean.

Crumley nodded.

The old man shoved his cane under his trembling hands and hoisted himself up. Crumley tried to help, but the fiery look the old man shot him moved him away.

“Stand aside!”

The old man battered the hardwood floor with his cane, as if punishing it for the bad news, and was out the door.

We followed him out into that mist and fog and rain where God’s light had just failed in Venice, southern California.

We walked into the morgue with a man eighty-two years old, but when we came out he was one hundred and ten, and could no longer use his cane. The fire was gone from his eyes, so he didn’t even beat us off as we tried to help him out to the car and he was mourning over and over, “My God, who gave him that awful haircut? When did that happen?” He babbled because he needed to talk nonsense. “Did you do that to him?” he cried to no one. “Who did that? Who?”

I know, I thought, but didn’t tell, as we got him out of the car and back to sit in his own place on that cold bench where the other old men waited, pretending not to notice our return, their eyes on the ceiling or the floor, waiting until we were gone so they could decide whether to stay away from the stranger their old friend had become or move closer to keep him warm.

Crumley and I were very quiet as we drove back to the as-good-as-empty canaries-for-sale house.

I stood outside the door while Crumley went in to look at the blank walls of the old man’s room and look at the names, the names, the names, William, Willy, Will, Bill. Smith. Smith. Smith, fingernail-scratched there in the plaster, making himself immortal.

When he came out, Crumley stood blinking back into the terribly empty room.

“Christ,” he murmured.

“Did you read the words on the wall?”

“All of them.” Crumley looked around and was dismayed to find himself outside the door staring in. “ ‘He’s standing in the hall.’ Who stood here?” Crumley turned to measure me. “Was it you?”

“You know it wasn’t,” I said, edging back.